The Jelly Effect: How To Make Your Communication Stick Order Printed Copy

- Author: Andy Bounds

- Size: 3.87MB | 257 pages

- |

Others like the jelly effect: how to make your communication stick Features >>

The Leader Who Had No Title

Excellence: How To Pursue An Excellent Spirit

Building Your Self-Image

The Obstacle Is The Way

Know Your Limits -- Then Ignore Them

Give And Take - A Revolutionary Approach To Success

As A Man Thinketh

The Unemployed Millionaire

7 Laws You Must Honor To Have Uncommon Success

Three Feet From Gold

About the Book

"The Jelly Effect" by Andy Bounds is a guide to effective communication, focusing on how to make your message memorable and impactful. The book provides practical tips and techniques for improving your communication skills and influencing others in a positive way. Bounds uses the analogy of jelly to illustrate how communication should be clear, concise, and sticky to resonate with your audience. Ultimately, the book highlights the importance of connecting with others and delivering messages that truly stick.

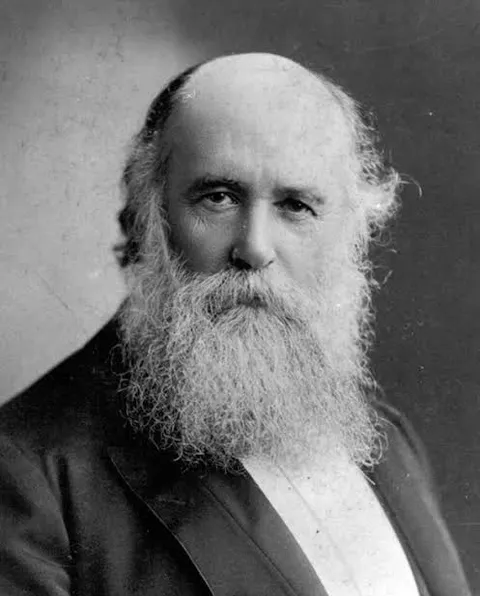

John Alexander Dowie

By John Alexander Dowie (1847 – 1907)

I sat in my study in the parsonage of the Congregational Church at Newtown, a suburb of the beautiful city of Sydney, Australia. My heart was very heavy, for I had visited the sick and dying beds of more than thirty of my flock, and I had cast the dust to its kindred dust into more than forty graves within a few weeks. Where, oh where, was He Who used to heal His suffering children? No prayer for healing seemed to reach His ear, and yet I knew His hand had not been shortened. Still it did not save from death even those for whom there was so much in life to live for God and others. Strong men, fathers, good citizens, and more than all, true Christians sickened with a putrid fever, suffered nameless agonies, passed into delirium, sometimes with convulsions, and then died.

Oh, what aching voids were left in many a widowed or orphaned heart. There were many homes where, one by one, the little children, the youths and the maidens lay stricken, and after a hard struggle with the foul disease, they too, lay cold and dead. It seemed sometimes as if I could almost hear the triumphant mockery of evil ringing in my ear whilst I spoke to the bereaved ones the words of Christian hope and consolation. Disease, the foul offspring of its father, Satan, and its mother Sin, was defiling and destroying the earthly temples of God’s children and there was no deliverance.

There I sat with sorrow-bowed head for my afflicted people, until the bitter tears came to relieve my burning heart. Then I prayed for some message, and oh, how I longed to hear some words from Him Who wept and sorrowed for the suffering long ago, a Man of Sorrows and Sympathies. The words of the Holy Ghost inspired In Acts 10:38, stood before me all radiant with light, revealing Satan as the Defiler, and Christ as the Healer. My tears were wiped away, my heart strong, I saw the way of healing, and the door thereto was opened wide, so I said, “God help me now to preach the Word to all the dying around, and tell them how Satan still defiles, and Jesus still delivers, for He is just the same today.”

A loud ring and several raps at the outer door, a rush of feet, and there at my door stood two panting messengers who said, “Oh, come at once, Mary is dying; come and pray. “With just a feeling as a shepherd has who hears that his sheep are being torn from the fold by a cruel wolf, I rushed from my house, ran without my hat down the street, and entered the room of the dying maiden. There she lay groaning and grinding her clenched teeth in the agony of the conflict with the destroyer. The white froth, mingled with her blood, oozing from her pale and distorted mouth. I looked at her and then my anger burned. “Oh,” I thought, “for some sharp sword of heavenly temper keen to slay this cruel foe who is strangling that lovely maiden like an invisible serpent, tightening his deadly coils for a final victory.”

In a strange way, It came to pass; I found the sword I needed was in my hands, and in my hand I hold it still and never will I lay It down. The doctor, a good Christian man, was quietly walking up and down the room, sharing the mother’s pain and grief. Presently he stood at my side and said, “Sir, are not God’s ways mysterious?” Instantly the sword was flashed in my hand, the Spirit’s sword, the Word of God. “God’s way?!” I said, pointing to the scene of conflict, “How dare you call that God’s way of bringing His children home from earth to Heaven? No sir, that is the devil’s work and it is time we called on Him Who came to destroy the work of the devil, to slay that deadly foul destroyer, and to save this child. Can you pray, Doctor, can you pray the prayer of faith that saves the sick?” At once, offended at my words, my friend was changed, and saying,” You are too much excited, sir, it is best to say ‘God’s will be done,’” and he left the room.

Excited?! The word was quite inadequate for I was almost frenzied with divinely imparted anger and hatred of that foul destroyer, disease, which was doing Satan’s will. “It is not so,” I exclaimed, “no will of God sends such cruelty, and I shall never say ‘God’s will be done’ to Satan’s works, which God’s own Son came to destroy, and this is one of them.” Oh, how the Word of God was burning in my heart: “Jesus of Nazareth went about doing good, and healing all that were oppressed of the devil; for God was with Him.” And was not God with me? And was not Jesus there and all His promises true? I felt that it was even so, and turning to the mother I inquired,” Why did you send for me?” To which she answered, “Do pray, oh pray for her that God may raise her up.” So we prayed.

What did I say? It may be that I cannot recall the words without mistake, but words are in themselves of small importance. The prayer of faith may be a voiceless prayer, a simple heartfelt look of confidence into the face of Christ. At such moment, words are few, but they mean much, for God is looking at the heart. Still, I can remember much of that prayer unto this day, and asking God to aid, I will attempt to recall it. I cried, “Our Father, help! and Holy Spirit, teach me how to pray. Plead Thou for us, oh, Jesus, Savior, Healer, Friend, our Advocate with God the Father. Hear and heal, Eternal One! From all disease and death, deliver this sweet child of yours. I rest upon the Word. We claim the promise now. The Word is true, ‘I am the Lord that heals thee.’ Then heal her now. The Word is true, ‘I am the Lord, I change not.’ Unchanging God, then prove Yourself the healer now. The Word is true. ‘These signs shall follow them that believe in My Name, they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover.’ And I believe and I lay hands in Jesus’ Name on her and claim this promise now. Your Word is true. ‘The prayer of faith shall save the sick. Trusting in You alone. I cry. Oh, save her now, for Jesus’ sake. Amen!”

Then, the maid lay in sleep so deep and sweet that the mother asked in a low whisper, “Is she dead?” “No,” I answered, in a whisper lower still. “Mary will live; the fever is gone. She is perfectly well and sleeping as an infant sleeps.” I was smoothing the long dark hair from her now peaceful brow, and feeling the steady pulsation of her heart and cool moist hands. I saw that Christ had heard, and that once more, as long ago in Peter’s house, “He touched her and the fever left her.” Turning to the nurse, I said, “Get me at once, please, a cup of cocoa and several slices of bread and butter.” Beside the sleeping maid we sat quietly and almost silently until the nurse returned, and then I bent over her and snapping my fingers called, “Mary!”

Instantly she woke, smiled and said, “Oh, sir, when did you come? I have slept so long;” then stretching her arms out to meet her mother’s embrace, she said, “Mother, I feel so well.” “And hungry, too?” I asked, pouring some of the cocoa in a saucer and offering it to her when cooled by my breath. “Yes, hungry too,” she answered with a little laugh, and drank and ate again, and yet again until all was gone. In a few minutes, she fell asleep, breathing easily and softly. Quietly thanking God. We left her bed and went to the next room where her brother and sister also lay sick of the same fever. With these two, we prayed and they were healed too. The following day all three were well and in a week or so they brought me a little letter and a gift of gold, two sleeve links with my monogram, which I wore for many years. As I went away from the home where Christ as the Healer had been victorious, I could not but have somewhat in my heart of the triumphant song that rang through Heaven, and yet I was not a little amazed at my own strange doings, and still more at my discovery that He is just the same today.

Excerpt from the Sermons of John Alexander Dowie Champions of Faith by Gordon Lindsay

By John Alexander Dowie (1847 – 1907)

I sat in my study in the parsonage of the Congregational Church at Newtown, a suburb of the beautiful city of Sydney, Australia. My heart was very heavy, for I had visited the sick and dying beds of more than thirty of my flock, and I had cast the dust to its kindred dust into more than forty graves within a few weeks. Where, oh where, was He Who used to heal His suffering children? No prayer for healing seemed to reach His ear, and yet I knew His hand had not been shortened. Still it did not save from death even those for whom there was so much in life to live for God and others. Strong men, fathers, good citizens, and more than all, true Christians sickened with a putrid fever, suffered nameless agonies, passed into delirium, sometimes with convulsions, and then died.

Oh, what aching voids were left in many a widowed or orphaned heart. There were many homes where, one by one, the little children, the youths and the maidens lay stricken, and after a hard struggle with the foul disease, they too, lay cold and dead. It seemed sometimes as if I could almost hear the triumphant mockery of evil ringing in my ear whilst I spoke to the bereaved ones the words of Christian hope and consolation. Disease, the foul offspring of its father, Satan, and its mother Sin, was defiling and destroying the earthly temples of God’s children and there was no deliverance.

There I sat with sorrow-bowed head for my afflicted people, until the bitter tears came to relieve my burning heart. Then I prayed for some message, and oh, how I longed to hear some words from Him Who wept and sorrowed for the suffering long ago, a Man of Sorrows and Sympathies. The words of the Holy Ghost inspired In Acts 10:38, stood before me all radiant with light, revealing Satan as the Defiler, and Christ as the Healer. My tears were wiped away, my heart strong, I saw the way of healing, and the door thereto was opened wide, so I said, “God help me now to preach the Word to all the dying around, and tell them how Satan still defiles, and Jesus still delivers, for He is just the same today.”

A loud ring and several raps at the outer door, a rush of feet, and there at my door stood two panting messengers who said, “Oh, come at once, Mary is dying; come and pray. “With just a feeling as a shepherd has who hears that his sheep are being torn from the fold by a cruel wolf, I rushed from my house, ran without my hat down the street, and entered the room of the dying maiden. There she lay groaning and grinding her clenched teeth in the agony of the conflict with the destroyer. The white froth, mingled with her blood, oozing from her pale and distorted mouth. I looked at her and then my anger burned. “Oh,” I thought, “for some sharp sword of heavenly temper keen to slay this cruel foe who is strangling that lovely maiden like an invisible serpent, tightening his deadly coils for a final victory.”

In a strange way, It came to pass; I found the sword I needed was in my hands, and in my hand I hold it still and never will I lay It down. The doctor, a good Christian man, was quietly walking up and down the room, sharing the mother’s pain and grief. Presently he stood at my side and said, “Sir, are not God’s ways mysterious?” Instantly the sword was flashed in my hand, the Spirit’s sword, the Word of God. “God’s way?!” I said, pointing to the scene of conflict, “How dare you call that God’s way of bringing His children home from earth to Heaven? No sir, that is the devil’s work and it is time we called on Him Who came to destroy the work of the devil, to slay that deadly foul destroyer, and to save this child. Can you pray, Doctor, can you pray the prayer of faith that saves the sick?” At once, offended at my words, my friend was changed, and saying,” You are too much excited, sir, it is best to say ‘God’s will be done,’” and he left the room.

Excited?! The word was quite inadequate for I was almost frenzied with divinely imparted anger and hatred of that foul destroyer, disease, which was doing Satan’s will. “It is not so,” I exclaimed, “no will of God sends such cruelty, and I shall never say ‘God’s will be done’ to Satan’s works, which God’s own Son came to destroy, and this is one of them.” Oh, how the Word of God was burning in my heart: “Jesus of Nazareth went about doing good, and healing all that were oppressed of the devil; for God was with Him.” And was not God with me? And was not Jesus there and all His promises true? I felt that it was even so, and turning to the mother I inquired,” Why did you send for me?” To which she answered, “Do pray, oh pray for her that God may raise her up.” So we prayed.

What did I say? It may be that I cannot recall the words without mistake, but words are in themselves of small importance. The prayer of faith may be a voiceless prayer, a simple heartfelt look of confidence into the face of Christ. At such moment, words are few, but they mean much, for God is looking at the heart. Still, I can remember much of that prayer unto this day, and asking God to aid, I will attempt to recall it. I cried, “Our Father, help! and Holy Spirit, teach me how to pray. Plead Thou for us, oh, Jesus, Savior, Healer, Friend, our Advocate with God the Father. Hear and heal, Eternal One! From all disease and death, deliver this sweet child of yours. I rest upon the Word. We claim the promise now. The Word is true, ‘I am the Lord that heals thee.’ Then heal her now. The Word is true, ‘I am the Lord, I change not.’ Unchanging God, then prove Yourself the healer now. The Word is true. ‘These signs shall follow them that believe in My Name, they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover.’ And I believe and I lay hands in Jesus’ Name on her and claim this promise now. Your Word is true. ‘The prayer of faith shall save the sick. Trusting in You alone. I cry. Oh, save her now, for Jesus’ sake. Amen!”

Then, the maid lay in sleep so deep and sweet that the mother asked in a low whisper, “Is she dead?” “No,” I answered, in a whisper lower still. “Mary will live; the fever is gone. She is perfectly well and sleeping as an infant sleeps.” I was smoothing the long dark hair from her now peaceful brow, and feeling the steady pulsation of her heart and cool moist hands. I saw that Christ had heard, and that once more, as long ago in Peter’s house, “He touched her and the fever left her.” Turning to the nurse, I said, “Get me at once, please, a cup of cocoa and several slices of bread and butter.” Beside the sleeping maid we sat quietly and almost silently until the nurse returned, and then I bent over her and snapping my fingers called, “Mary!”

Instantly she woke, smiled and said, “Oh, sir, when did you come? I have slept so long;” then stretching her arms out to meet her mother’s embrace, she said, “Mother, I feel so well.” “And hungry, too?” I asked, pouring some of the cocoa in a saucer and offering it to her when cooled by my breath. “Yes, hungry too,” she answered with a little laugh, and drank and ate again, and yet again until all was gone. In a few minutes, she fell asleep, breathing easily and softly. Quietly thanking God. We left her bed and went to the next room where her brother and sister also lay sick of the same fever. With these two, we prayed and they were healed too. The following day all three were well and in a week or so they brought me a little letter and a gift of gold, two sleeve links with my monogram, which I wore for many years. As I went away from the home where Christ as the Healer had been victorious, I could not but have somewhat in my heart of the triumphant song that rang through Heaven, and yet I was not a little amazed at my own strange doings, and still more at my discovery that He is just the same today.

Excerpt from the Sermons of John Alexander Dowie Champions of Faith by Gordon Lindsay

Trapped for All Eternity

My dear Globdrop, I have received your perspective concerning your man’s most recent incident. He drew swords with his atheist classmate and succeeded, did he? He made the Enemy and the hope of a hereafter seem almost “reasonable”? In those ten minutes, the clouds pulled back and heaven appeared to triumph over hell, did it? You call it “a true embarrassment . . . a humiliating defeat.” You repeatedly assure me that you “take full responsibility.” O my dear nephew, what’s next? Did you, borrowing a human expression, require a shoulder to cry on? A nodding head and listening ear? Words of affirmation? Stand upright, soldier. Yours is not the only name to be pulled down into disgrace. All is far from lost. Though you slouch in shame with your talons curled, consider that mere “reasoning” does not frighten us (though we do not encourage it). A “reasonable” God, a “reasonable” eternity, and a “reasonable” heaven are still no God, no eternity, and no heaven — so long as “reasonable” goes unaccompanied with “desirable.” A God and a heaven no one wants are the only kind we will approve. Just a Few More Hours This unwelcomed eternity is, from all indications, your man’s current conception. The heaven he hotly debates is not the heaven he really wants. He is not one to strive to enter the narrow gate. He is “a few more hours” kind of man. I remember that splendid night like it was yesterday. One of their comedians took the stage to joke that he feared the Enemy would return on his wedding night. How would he respond when his “Lord” came to meet him? “Give me a few more hours.” The audience bellowed uproarious laughter. This, Globdrop, is comedy! Dark, damning, delicious. What this man said captures the subtitles of their lives: “Lord, give me a few more hours to make my mark on the world!” “Give me a little longer to get married and have children!” “Lord, let me grow old and spent. Then return!” Not yet, Lord — give me just a few more hours! For all the “Christian” talk (or debating), great masses of them still consider heaven an intrusion, a cloud moving over their day at the beach, a mere shadow interrupting the earthly substance. Their decaying bodies, grey hairs, and slowing minds trigger fear, not anticipation, for what lies ahead. These are runners who slow near the finish line, soldiers who do not want the war to end, farmers who groan at the first signs of harvest, prodigals looking back longingly at the city they can no longer afford. Their hearts are here; their heaven is earth. If not forced over the cliff by death, many would say, “a few more hours” for all eternity. Demon’s History of Heaven The secret, then, is this: we do not need to waste time trying to make atheists of those who stubbornly believe that the Enemy or heaven is real; we need only convince them that it’s nothing to leave earth for. And thankfully, we do not need to deceive them on this point. I was just a young devil during the Rebellion. The humans scratch their furry heads, perplexed how we could have ever sinned; they gaze up at the stars, wondering how perfect creatures could ever fall. They never consider that our Father Below “fell like lightning from heaven” in a grand escape from their precious heaven. Sure, the Enemy was well at hand to twist the story, labeling it as our being cast out in defeat, but what he calls an insurrection, we know as emancipation. We could not linger for one more millennium locked in that kennel he calls heaven. Our Father discovered (almost too late) that the Enemy allows only spaniels in that place, puppies wagging their peppy tails, yapping incessant praises, jumping up and down for that eternal belly scratch he calls joy. Our Dark Lord Lucifer, deciding then that he would not allow us to be of the servile breed, snapped the leash from such a place. Here again, the thinkers of men scratch their heads wondering why they — and not we demons — were sent “redemption.” As their preachers drool with self-congratulation, they would be shocked to discover the truth: we wouldn’t want it if he offered it. We know what “heaven” on his terms means. Were the door to swing open to us, we would slam it once again. We’ve had enough of his ball-fetching. Danger of Desire Yet the vermin actually applaud when he takes them for slaves. He, of course, gives each chain a pretty name — joy, peace, goodness, love, and the rest. What effective propaganda that he even goes so far as to move the Warden of his own presence into them to ensure they live as he demands, all the while convincing them that this is some precious gift. It is when they begin to see things in this concussed way — God, heaven, holiness as a treasure — that things get dangerous. Humans in this condition have been known to do more damage to our Father’s kingdom than ten thousand of those who, for all their talk, just want a few more hours. Men have sung on their way to the gallows. Women have crossed oceans to tell news of the Enemy to subjects we thought firmly in our grasp. Young children even, giving up a life unlived because of this infection. The hope of heaven to them has been a shield against our most reliable weapons: suffering, grief, sickness, and pain. The servitude that they mistake for freedom would almost make us laugh — if it did not rob us of our supper. Floating Clouds, Plucking Harps Heaven must remain — if it must remain — as merely the next best thing when they are evicted from this earth. Keep heaven in the peripheral: a blinding blur; the butt of a joke; a hazy, undesirable existence of floating in clouds and plucking harps. Let them think they are praying “on earth as it is in heaven” when they really mean “in heaven as it is on earth.” Far from fainting at such a belief, we see in it the opportunity to glorify our Father Below. When they refuse the Enemy’s feast to check on the fields and oxen they bought, or when they excuse themselves because they just got married and need a few more hours, all see the truth. How those howls shook hell when that young rich man — and every rich man since — finally turned away dejected. So yes, dear Globdrop, allow heaven to be “reasonable” to your man, at least for now. But never allow it to be more. Let him contest for the idea of heaven and drop the thought once he sits down to eat lunch, scrolls mindlessly through his phone, or watches a movie with his girlfriend — send him immediately back to our world. The only heaven we can endure — and the only heaven that will deliver your patient safely to us — is the heaven for which no one really wants to leave earth. Your unamused uncle, Grimgod Article by Greg Morse