Others like killjoys - the seven deadly sins Features >>

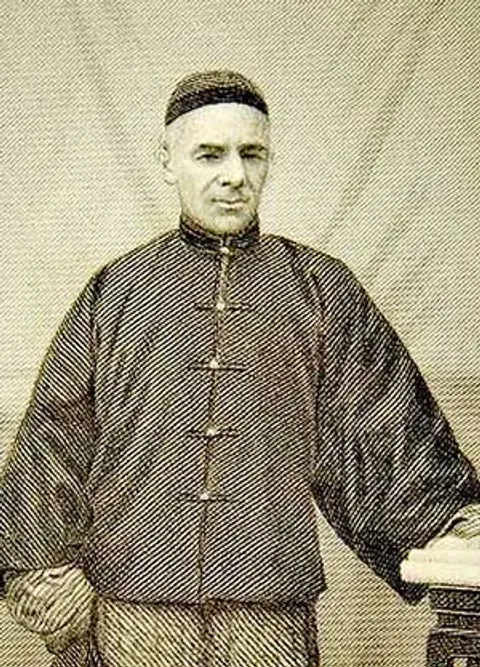

William Chalmers Burns

William Chalmers Burns was born in the Manse of Dun, in Angus, on April Ist, 1815. He was the third son of the Parish Church minister there. After leaving school, he went to Edinburgh to be apprenticed with an uncle to the legal profession. His eldest sister, a gay young lady, was converted to God, and became a bright witness for the Lord Jesus in 1831, and it was by means of her decided testimony that William was first awakened to a sense of his need of salvation, and led to put his trust in the Son of God, as his Redeemer and Saviour.

It was shortly after his conversion that he walked into the manse of Kilsyth, where the family then resided, having walked on foot the thirty-six miles from Edinburgh, to tell his mother and his sisters the glad news of his conversion, and to say that his desire now was to relinquish his study of law, and devote himself entirely to the preaching of the Gospel of God’s grace to his fellowmen.

And this he did heartily and with all his might, first in the neglected Parts of Scotland, and latterly among many heathen millions of the great Chinese Empire, then scarcely touched by the feet of God’s messengers of peace.

Mr. Burns’s name came into prominence in connection with a wonderful work of grace in Dundee, while he was preaching for Robert Murray M’Cheyne, then on a visit to Palestine, for the evangelization of the Jews. During Mr. Burns’s preaching in Dundee, a remarkable awakening took place; thousands were aroused to their condition in the sight of God, truly converted, and set on the heavenward way.

Remarkable scenes were witnessed in the old church of St. Peter’s, near to which M’Cheyne’s body now lies, awaiting the first resurrection. It was on the evening of a Lord’s Day in Kilsyth, after preaching to a crowded congregation, that Mr. Burns felt constrained to intimate to the people that he would preach to the people in the open air, before returning to Dundee the following day.

Deeply burdened with the souls of the people, he went into the village and invited the people, who thronged into the old church, until every seat and passage was filled. And the Lord helped His servant to preach straight to the people with great power, with the result that the whole congregation became melted under the message, many weeping aloud and crying to God for mercy. A glorious work of conversion followed.

Meetings for prayer and preaching of the Gospel continued in the churchyard, the market-place and elsewhere for weeks, while Mr. Burns returned to Dundee to resume his ministry. The work progressed in Dundee with increased interest, until the return of Mr. M’Cheyne, who greatly rejoiced in all that the Lord had done during his absence, through the ministry of His servant.

There was no jealousy, but the deepest gratitude, and these two true ministers of Christ rejoiced together over the Lord’s doings, which were indeed marvellous in their eyes.

From that time onward, until the Lord’s call came to go to China, Mr. Burns gave himself almost wholly to itinerant Gospel preaching, through Perthshire, up as far north as Aberdeen, preaching in barns, on market-places, and wherever the people could be gathered together to hear the Word. His message was plain, and to the point; thousands were awakened and many saved. But the adversary opposed. Time and again Mr. Burns was stoned, and bore the marks of these brands of the enemy for many days.

Believing it to be the call of the Lord, he went forth to China as the first missionary of the Presbyterian Church of England, in June, 1847. When questioned by those interested in his out-going, how long it would take him to prepare for the voyage, he replied with all simplicity, “I will be ready to go to-morrow.”

On a brief visit to his home, to take farewell of his sister, he silently wrung her hand, took a last glance around their old home, and with a small bag in his hand and his mother’s plaid across his arm, went forth, in the Name of the Lord with the Gospel to China’s benighted people, of whom it was said “a million a month” were dying without having once heard the Gospel.

For years this solitary witness toiled alone, at times with a few helpers, in the great heathen land, amid overwhelming hindrances, but his faith in God never faltered. On and on he went, sowing the seed which others would reap, until he reached the borders of the great kingdom of Manchuria, where, in a small, comfortless room in Nieu-chang, wearied and worn in labours abundant, he fell asleep on April 4th, 1868, his last audible words being, “For Thine is the Kingdom and the Power and the Glory.”

It is of this great land that the story of grace related in the following pages is told, and those who saw and shared in its joyful results, say that it was no doubt part of the result of William Burns’s sowing, in his earlier years in China.

William Chalmers Burns was born in the Manse of Dun, in Angus, on April Ist, 1815. He was the third son of the Parish Church minister there. After leaving school, he went to Edinburgh to be apprenticed with an uncle to the legal profession. His eldest sister, a gay young lady, was converted to God, and became a bright witness for the Lord Jesus in 1831, and it was by means of her decided testimony that William was first awakened to a sense of his need of salvation, and led to put his trust in the Son of God, as his Redeemer and Saviour.

It was shortly after his conversion that he walked into the manse of Kilsyth, where the family then resided, having walked on foot the thirty-six miles from Edinburgh, to tell his mother and his sisters the glad news of his conversion, and to say that his desire now was to relinquish his study of law, and devote himself entirely to the preaching of the Gospel of God’s grace to his fellowmen.

And this he did heartily and with all his might, first in the neglected Parts of Scotland, and latterly among many heathen millions of the great Chinese Empire, then scarcely touched by the feet of God’s messengers of peace.

Mr. Burns’s name came into prominence in connection with a wonderful work of grace in Dundee, while he was preaching for Robert Murray M’Cheyne, then on a visit to Palestine, for the evangelization of the Jews. During Mr. Burns’s preaching in Dundee, a remarkable awakening took place; thousands were aroused to their condition in the sight of God, truly converted, and set on the heavenward way.

Remarkable scenes were witnessed in the old church of St. Peter’s, near to which M’Cheyne’s body now lies, awaiting the first resurrection. It was on the evening of a Lord’s Day in Kilsyth, after preaching to a crowded congregation, that Mr. Burns felt constrained to intimate to the people that he would preach to the people in the open air, before returning to Dundee the following day.

Deeply burdened with the souls of the people, he went into the village and invited the people, who thronged into the old church, until every seat and passage was filled. And the Lord helped His servant to preach straight to the people with great power, with the result that the whole congregation became melted under the message, many weeping aloud and crying to God for mercy. A glorious work of conversion followed.

Meetings for prayer and preaching of the Gospel continued in the churchyard, the market-place and elsewhere for weeks, while Mr. Burns returned to Dundee to resume his ministry. The work progressed in Dundee with increased interest, until the return of Mr. M’Cheyne, who greatly rejoiced in all that the Lord had done during his absence, through the ministry of His servant.

There was no jealousy, but the deepest gratitude, and these two true ministers of Christ rejoiced together over the Lord’s doings, which were indeed marvellous in their eyes.

From that time onward, until the Lord’s call came to go to China, Mr. Burns gave himself almost wholly to itinerant Gospel preaching, through Perthshire, up as far north as Aberdeen, preaching in barns, on market-places, and wherever the people could be gathered together to hear the Word. His message was plain, and to the point; thousands were awakened and many saved. But the adversary opposed. Time and again Mr. Burns was stoned, and bore the marks of these brands of the enemy for many days.

Believing it to be the call of the Lord, he went forth to China as the first missionary of the Presbyterian Church of England, in June, 1847. When questioned by those interested in his out-going, how long it would take him to prepare for the voyage, he replied with all simplicity, “I will be ready to go to-morrow.”

On a brief visit to his home, to take farewell of his sister, he silently wrung her hand, took a last glance around their old home, and with a small bag in his hand and his mother’s plaid across his arm, went forth, in the Name of the Lord with the Gospel to China’s benighted people, of whom it was said “a million a month” were dying without having once heard the Gospel.

For years this solitary witness toiled alone, at times with a few helpers, in the great heathen land, amid overwhelming hindrances, but his faith in God never faltered. On and on he went, sowing the seed which others would reap, until he reached the borders of the great kingdom of Manchuria, where, in a small, comfortless room in Nieu-chang, wearied and worn in labours abundant, he fell asleep on April 4th, 1868, his last audible words being, “For Thine is the Kingdom and the Power and the Glory.”

It is of this great land that the story of grace related in the following pages is told, and those who saw and shared in its joyful results, say that it was no doubt part of the result of William Burns’s sowing, in his earlier years in China.

witnessing with gospel tracts

Gospel tracts and pamphlets are very important tools in evangelism. The printing press was a wonderful gift from God and has been used greatly for the glory of Jesus Christ. The printed page can greatly multiply our efforts in the service of the Lord and tracts can oftentimes go places where we cannot go. Be Careful About the Message The first consideration in the use of Gospel tracts is to be certain that the content is scriptural. There are three problems with many gospel tracts: 1. Many tracts do not contain a clear and biblical presentation of the gospel. Many refer to salvation in an unscriptural and confusing manner, such as "asking Jesus into my heart" or "giving my life to Christ." Salvation is not to give one's life to Christ, but is to trust the finished atonement of Christ. Nowhere in the New Testament do we see the Lord Jesus or the Apostles telling people to give their lives to Christ or to ask Jesus into their hearts. We need to follow the Bible very carefully in the terminology we use so that people are not confused and so they do not make false professions of faith. 2. The second serious drawback is that most tracts do not deal with repentance. Most don't even mention the word or even hint at the concept, yet the Lord Jesus Christ and His apostles preached repentance plainly and demanded it from those who would be saved. Salvation only comes by "repentance toward God, and faith toward our Lord Jesus Christ" (Acts 20:21). Any presentation of the gospel should include the fact that God "now commandeth all men every where to repent" (Acts 17:30). Whether or not the word "repentance" is used in a gospel tract, the idea should be. What is repentance? It is a turning, a change of direction (1 Thess. 1:9). When I receive Jesus Christ as my Lord and Savior, I am turning my back to the old life. 3. Another problem is that many simply do not give enough information. Large numbers of people in North America today are as ignorant of the true God of the Bible and of the basics of the Gospel of the Lord Jesus Christ as any Hindu in darkest Asia. It is crucial that we begin with the basics with these people, and that we explain biblical terms thoroughly, otherwise, when they hear terms such as "saved," "believe," "Christ," "God," "sin," they won't have the proper idea of what we are talking about, and any "profession" they make will be empty. The following are a few examples of gospel tracts that include repentance: "The Bridge to Eternal Life." This full-color pamphlet is also illustrated. [Detroit Baptist Theological Seminary, Majestic Media, 810-725-5800] "Have You Considered This?" [Dennis Costella, Fundamental Evangelistic Association, 1476 W. Herndon, Suite 104 Fresno, CA 93711, 559-438-0080. [Also available online at https://www.feasite.org/Tracts/fbconsdr.htm] "I'm a Pretty Good Person" is one of the many tracts published by the Fellowship Tract League. It is a good tract to show people that their good works and religion won't take them to heaven. [available from Sermon and Song Ministries, P.O. Box 109, Ravenna, OH 44266, www.sermonandsong.org; also available from Fellowship Tract League, P.O. Box 164, Lebanon, OH 45036, 513-494-1075, http://www.fellowshiptractleague.org/] "The Little Red Book." This 12-page pamphlet is illustrated and has been effective. [Little Red Book, P.O. Box 341, N. Greece, NY 14515 or P.O. Box 7195, Greensboro, NC 27417, LRB@frontiernet.net, 585-225-0715] "The Most Important Thing You Must Consider." This tract is strong on God's holiness and just punishment of sin and the necessity of repentance. [Faith Baptist Church, 105-01 37th Avenue, Corona, NY 11368 718-457-5651, http://www.studygodsword.com/fbcpress/tracts.html] "What Is Your Life?" This pamphlet is illustrated. [Operation Somebody Cares, 1131 Brentwood Drive, Collinsville, VA 24078, 276-647-5328, http://www.operationsomebodycares.com] "What Must I Do to Be Saved" by the late Evangelist John R. Rice. [Sword of the Lord, Box 1099, Murfreesboro, TN 37130. 800-247-9673, booksales@swordofthelord.com] "Why Should I Let You into My Heaven?" [Dean Myers, deanmyers2@juno.com] Liberty Baptist Church in Greenville, Michigan, has a wide range of helpful Gospel tracts. [Pastor Mike Austin, Liberty Baptist Church, 11845 W. Carson City Road, Greenville, MI 48838. 616-754-7151, pastor@libertygospeltracts.com, http://www.libertygospeltracts.com/] Mercy and Truth Ministries has some interesting small tracts. One is titled "You Can Get to Heaven from ---------" and an edition can be obtained for each state in the U.S. [Mercy and Truth Ministries, Lawrence, KS 66049, 875-887-2203] Pilgrim Fundamental Baptist Press publishes a tract that is designed to leave with a tip after a meal. On the outside it says, "Thank you and here are 2 tips for you!" On the inside it states that Tip #1 is a monetary token of appreciation for your service, and Tip #2 is a Gospel tract that explains how to be saved. It is large enough to hold a standard tract. [Pilgrim Fundamental Baptist Press, P.O. Box 1832, Elkton, MD 21922] Things to Remember When Passing Out Tracts Giving out tracts is something every born again believer can do, young or old. 1. Remember that it is each believer's responsibility to give out the gospel (see Matt. 28:19-20; Mk. 16:15; Luke 24:45-48; Acts 1:8; 2 Cor. 5:17-21; Phil. 2:16; 2 Tim. 4:5). 2. Remember that by giving out the gospel you are offering the greatest gift in the world. When we give out the gospel we are offering dead people life; we are offering poor people riches; we are offering sick people healing; we are offering lost people salvation. 3. It is wise to read the tracts first yourself before giving them out to others. This way you will know exactly what it says and you can refer to it when you talk to people. Also, by first reading tracts before giving them away you can see if the tract contains something that is not true or leaves out something important such as repentance. 4. Make a commitment to give out so many tracts each week. 5. Always be pleasant and polite. Remember that you are a complete stranger to the people you are approaching. Ask kindly, "May I give you something special to read?" or "I have some Good News for You" or "May I give you something that has been a blessing in my own life?" If they are busy ask them to put it in their pocket and read at home. 6. Keep in mind that the goal is not merely to give out tracts but to find opportunities to witness to people about the Lord Jesus Christ with the goal of leading them to salvation. Use the tracts to open the conversation, and when you find someone who is interested take the time to talk further with him and see if he or she is willing to meet again. We must remember that it is not enough to give out tracts; the objective is to see people come to Christ and baptized and discipled (Matt. 28:19-20). 7. Don't get upset or discouraged if someone says something against Jesus and the Bible or they mock you and what you are doing. "For unto you it is given in the behalf of Christ, not only to believe on him, but also to suffer for his sake" (Phil. 1:29; see also Matt. 5:11-12; Jn. 15:20; Luke 9:26). 8. Give out tracts to those who look like they might be interested and to those who don't. We cannot look upon the hearts of men and we cannot know who God might be dealing with. Jesus said preach the gospel to every creature (Mk. 16:15). "In the morning sow thy seed, and in the evening withhold not thine hand: for thou knowest not whether shall prosper, either this or that, or whether they both shall be alike good" (Ecc. 11:6). Ecclesiastes 11:1 says, "Cast thy bread upon the waters: for thou shalt find it after many days." This refers to the custom of casting seed on the marshy ground after a river such as the Nile had overflowed its banks, trusting that the seed will take root and bring forth a crop. "When the waters receded, the grain in the alluvial soil sprang up. 'Waters' express the seemingly hopeless character of the recipients of the charity; but it shall prove at last to have been not thrown away" (Jamieson, Fausset, Brown). 9. Be sure there is a name and address stamped on each tract so that if someone is interested they have a contact for further help. A gospel correspondence course is a good way to follow up on tract distribution. See the section on correspondence courses in our book "Ideas for Evangelism" for suggestions. This seems to be more effective in some places than others, but we have personally seen much fruit by this means. 10. One of the most important things about tract distribution is faithfulness and persistence. Some may be thrown away but others may find them. We have a man in our church who first got interested in Christ by reading a tract that was given to his friend. This has happened many times. God wants faithful workers. Don't get discouraged if nothing seems to be happening. We must do this work by faith, not by sight. Keep your eyes on the Lord and trust Him to accomplish His will and to give fruit and just continue to give out the gospel. "But this I say, He which soweth sparingly shall reap also sparingly; and he which soweth bountifully shall reap also bountifully" (2 Cor. 9:6). "Moreover it is required in stewards, that a man be found faithful" (1 Cor. 4:2). 11. Remember that our real enemy in tract distribution is not people, but the devil. He is the god of this world who is blinding the minds of the unbelievers (2 Cor. 4:4). Thus we must have on the whole armor of God as we go about this important work (Eph. 6:11-12). 12. Pray much for your tract distribution, both before and after. Pray that God will open the eyes of the people so that they desire to know Him and that they will read and understand the tracts. Updated July 21, 2008. First published January 15, 1998 by David Cloud, Fundamental Baptist Information Service, P.O. Box 610368, Port Huron, MI 48061. Used with permission.