-480.webp)

Collaborating With The Enemy (How To Work With People You Don’t Agree With Or Like Or Trust) Order Printed Copy

- Author: Adam Kahane

- Size: 2.37MB | 148 pages

- |

Others like collaborating with the enemy (how to work with people you don’t agree with or like or trust) Features >>

Ego Is The Enemy

Tough Times Never Last, But Tough People Do

How To Live An Extraordinary Life

An Unquiet Mind

The Difference Maker

7 Laws You Must Honor To Have Uncommon Success

None Of These Diseases

-160.webp)

Get Smart! How To Think And Act Like The Most Successful And Highest-Paid People In Every Field

101 Activities For Teaching Creativity And Problem Solving

Personal Development All-In-One For Dummies

About the Book

"Collaborating with the Enemy" by Adam Kahane is a guide on how to effectively work with individuals you may not necessarily agree with, like, or trust. The author offers practical strategies and techniques for overcoming obstacles and creating successful collaborations, emphasizing the importance of communication, empathy, and finding common ground. Kahane draws on his own experiences as a mediator and facilitator to provide valuable insights and tools for navigating challenging working relationships.

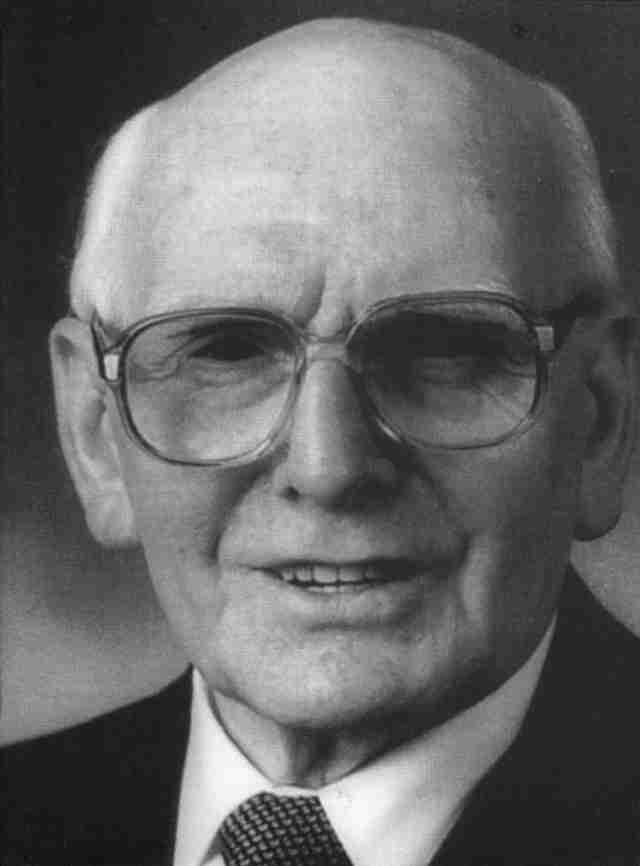

William Still

I recently read Dying to Live (Christian Focus, 1991), the autobiography of Scottish pastor William Still. I became interested in Still after reading his book The Work of the Pastor earlier this year.

The first half of Dying to Live tells about Still’s early years into young adulthood and his beginning in pastoral ministry. Still had an unsettled childhood. His parents were separated in his early years, and his father was an alcoholic. He was a sickly child who took refuge in music and became an accomplished pianist. He was part of the Salvation Army as a young man but then entered ministry in the Church of Scotland and served at the Gilcomston Church in his hometown of Aberdeen from 1945-1997.

The second half of the book deals with various aspects of Still’s pastoral ministry. Still was an evangelical. In his early ministry he worked with Billy Graham, Alan Redpath, and others in evangelistic events. With time, however, he moved away from what he came to call “evangelisticism” to develop a solid expositional ministry.

Still faced his fair share of hardships during the course of his ministry. When he moved away from pragmatic evangelistic methods, for example, more than two hundred people stopped attending his church almost overnight. In the preface, he references Martin Luther’s observation that there are three things which make a minister: study, prayer, and afflictions. He observes, “He who is not prepared to make enemies for Christ’s sake by the faithful preaching of the Word will never make lasting friends for Christ, either” (p. 93).

He describes one particularly difficult controversy early in his ministry when he confronted a group of disgruntled elders. At the end of one Sunday service, he read a statement confronting these men, which ended, “There you sit, with your heads down, guilty men. What would you say if I named you before the whole congregation? You stand condemned before God for your contempt of the Word and of his folk.” He adds, “The moment I had finished, I walked out of the pulpit. There was no last hymn—no benediction. I went right home. It was the hardest and most shocking thing I ever had to do in Gilcomston” (p. 124). That same week seven of his elders resigned and Still was called twice before his Presbytery to answer for the controversy. Yet, he endured.

Still maintains that in light of the unpleasantness one will face in the ministry that the minister of the Word must possess one quality in particular: “…I would say that this quality is courage: guts, sheer lion-hearted bravery, clarity of mind and purpose, grit. Weaklings are no use here. They have a place in the economy of God if they are not deliberate weaklings and stunted adults as Paul writes of both to the Romans and to the Corinthians. But weaklings are no use to go out and speak prophetically to men from God and declare with all compassion, as well as with faithfulness, the truth: the divine Word that cuts across all men’s worldly plans for their lives” (p. 140).

Still was a pioneer in several areas. First, he developed a pattern of preaching and teaching systematically through books of the Bible at a time when this was rarely done. He began a ministry of “consecutive Bible teaching” starting with the book of Galatians in 1947, calling this transition from “evangelisticism to systematic exposition … probably the most significant decision in my life” (p. 191).

He was also a pioneer in simplifying and integrating the ministry of the church. After noting how youth in the church were drifting away, even after extensive involvement in the church’s children’s ministry, Still writes, “I conceived the idea of ceasing all Sunday School after beginners and Primary age (seven years) and invited parents to have their children sit with them in the family pew from the age of eight” (p. 171). He laments “the disastrous dispersion of congregations by the common practice of segregating the church family into every conceivable category of division of ages, sexes, etc.” (p. 173).

Dying to Live is a helpful and encouraging work about the life and work of the minister and is to be commended to all engaged in the call of gospel ministry. As the title indicates, Still’s essential thesis is that in order to be effective in ministry the minister must suffer a series of deaths to himself (cf. John 12:24). On this he writes:

The deaths one dies before ministry can be of long duration—it can be hours and days before we minister, before the resurrection experience of anointed preaching. And then there is another death afterwards, sometimes worse than the death before. From the moment that you stand there dead in Christ and dead to everything you are and have and ever shall be and have, every breath you breathe thereafter, every thought you think, every word you say and deed you do, must be done over the top of your own corpse or reaching over it in your preaching to others. Then it can only be Jesus that comes over and no one else. And I believe that every preacher must bear the mark of that death. Your life must be signed by the Cross, not just Christ’s cross (and there is really no other) but your cross in his Cross, your particular and unique cross that no one ever died—the cross that no one ever could die but you and you alone: your death in Christ’s death (p. 136).

I recently read Dying to Live (Christian Focus, 1991), the autobiography of Scottish pastor William Still. I became interested in Still after reading his book The Work of the Pastor earlier this year.

The first half of Dying to Live tells about Still’s early years into young adulthood and his beginning in pastoral ministry. Still had an unsettled childhood. His parents were separated in his early years, and his father was an alcoholic. He was a sickly child who took refuge in music and became an accomplished pianist. He was part of the Salvation Army as a young man but then entered ministry in the Church of Scotland and served at the Gilcomston Church in his hometown of Aberdeen from 1945-1997.

The second half of the book deals with various aspects of Still’s pastoral ministry. Still was an evangelical. In his early ministry he worked with Billy Graham, Alan Redpath, and others in evangelistic events. With time, however, he moved away from what he came to call “evangelisticism” to develop a solid expositional ministry.

Still faced his fair share of hardships during the course of his ministry. When he moved away from pragmatic evangelistic methods, for example, more than two hundred people stopped attending his church almost overnight. In the preface, he references Martin Luther’s observation that there are three things which make a minister: study, prayer, and afflictions. He observes, “He who is not prepared to make enemies for Christ’s sake by the faithful preaching of the Word will never make lasting friends for Christ, either” (p. 93).

He describes one particularly difficult controversy early in his ministry when he confronted a group of disgruntled elders. At the end of one Sunday service, he read a statement confronting these men, which ended, “There you sit, with your heads down, guilty men. What would you say if I named you before the whole congregation? You stand condemned before God for your contempt of the Word and of his folk.” He adds, “The moment I had finished, I walked out of the pulpit. There was no last hymn—no benediction. I went right home. It was the hardest and most shocking thing I ever had to do in Gilcomston” (p. 124). That same week seven of his elders resigned and Still was called twice before his Presbytery to answer for the controversy. Yet, he endured.

Still maintains that in light of the unpleasantness one will face in the ministry that the minister of the Word must possess one quality in particular: “…I would say that this quality is courage: guts, sheer lion-hearted bravery, clarity of mind and purpose, grit. Weaklings are no use here. They have a place in the economy of God if they are not deliberate weaklings and stunted adults as Paul writes of both to the Romans and to the Corinthians. But weaklings are no use to go out and speak prophetically to men from God and declare with all compassion, as well as with faithfulness, the truth: the divine Word that cuts across all men’s worldly plans for their lives” (p. 140).

Still was a pioneer in several areas. First, he developed a pattern of preaching and teaching systematically through books of the Bible at a time when this was rarely done. He began a ministry of “consecutive Bible teaching” starting with the book of Galatians in 1947, calling this transition from “evangelisticism to systematic exposition … probably the most significant decision in my life” (p. 191).

He was also a pioneer in simplifying and integrating the ministry of the church. After noting how youth in the church were drifting away, even after extensive involvement in the church’s children’s ministry, Still writes, “I conceived the idea of ceasing all Sunday School after beginners and Primary age (seven years) and invited parents to have their children sit with them in the family pew from the age of eight” (p. 171). He laments “the disastrous dispersion of congregations by the common practice of segregating the church family into every conceivable category of division of ages, sexes, etc.” (p. 173).

Dying to Live is a helpful and encouraging work about the life and work of the minister and is to be commended to all engaged in the call of gospel ministry. As the title indicates, Still’s essential thesis is that in order to be effective in ministry the minister must suffer a series of deaths to himself (cf. John 12:24). On this he writes:

The deaths one dies before ministry can be of long duration—it can be hours and days before we minister, before the resurrection experience of anointed preaching. And then there is another death afterwards, sometimes worse than the death before. From the moment that you stand there dead in Christ and dead to everything you are and have and ever shall be and have, every breath you breathe thereafter, every thought you think, every word you say and deed you do, must be done over the top of your own corpse or reaching over it in your preaching to others. Then it can only be Jesus that comes over and no one else. And I believe that every preacher must bear the mark of that death. Your life must be signed by the Cross, not just Christ’s cross (and there is really no other) but your cross in his Cross, your particular and unique cross that no one ever died—the cross that no one ever could die but you and you alone: your death in Christ’s death (p. 136).

Where Does God Want Me to Work

How do I find God’s will for my life? It’s always a pressing question on the college campus, and especially in our day of unprecedented options. Like never before, in an anomaly in world history, students loosened from their community of origin, “going off” to college, now make decisions about their future with minimal influence or limitation from their adolescent context. “God wants to take you by the heart, not twist you by the arm.” Before asking, “Where is God calling me?” we would do well to first ponder, “Where has God already called me?” — not that your current callings won’t change or take a fresh direction in this formative season of life, but for a Christian, our objective calling from God always precedes our consciousness of it. If it is from him, he initiates. He makes the first move. This is true of our calling to salvation, and also true of any “vocational” assignment he gives us in the world. Consider Three Factors For the college student or young adult who may feel like a free agent — considering options and determining for yourself (and often by yourself) which direction to take — it’s important to acknowledge you are already moving in a direction, not standing still. You already have divine callings — as a Christian, as a church member, as a son or daughter, as a brother or sister, as a friend. And from within the matrix of those ongoing, already-active callings, you now seek God’s guidance for where to go from here. Given, then, that you are already embedded in a context, with concrete callings, how should you go about discerning God’s direction after graduation? Or how do you find God’s will for your work-life? Christians will want to keep three important factors in view. 1. What Kind of Work Do I Desire? First, we recognize, contrary to the suspicions that may linger in our unbelief, God is the happy God (1 Timothy 1:11), not a cosmic killjoy. In his Son, by his Spirit, he wants to shape and form our hearts to desire the work to which he’s calling us and, in some good sense, in this fallen world, actually enjoy the work. Sanctified, Spirit-given desire is not a liability, but an asset, to finding God’s will. The New Testament is clear that God means for pastors to aspire to the work of the pastoral ministry. And we can assume, as a starting point, that God wants the same for his children working outside the church. “Desire is a vital factor to consider, but in and of itself this doesn’t amount to a calling.” In 1 Peter 5:2, we find this remarkably good news about how God’s heart for our good and enduring joy stands behind his leading us vocationally. The text is about the pastoral calling, but we can see in it the God who calls us into any carefully appointed station. God wants pastors who labor “not under compulsion, but willingly, as God would have you.” How remarkable is it that working from aspiration and delight, not obligation and duty, would be “as God would have you.” This is the kind of God we have — the desiring (not dutiful) God, who wants workers who are desiring (not dutiful) workers. He wants his people, like their pastors, to do their work “with joy and not with groaning, for that would be of no advantage” to those whom they serve (Hebrews 13:17). So also, when the apostle Paul addresses the qualifications of pastors, he first mentions aspiration. “The saying is trustworthy: If anyone aspires to the office of overseer, he desires a noble task” (1 Timothy 3:1). God wants workers who want to do the work, not workers who do it simply out of a sense of duty. Behold your God, whose pattern is to take you by the heart, not twist you by the arm. Desire, though, does not make a calling on its own. It’s a common mistake to presume that seeming God-given desire is, on its own, a “calling.” Aspiration is a vital factor to consider, but in and of itself this doesn’t amount to a calling. Two additional factors remain in the affirmation of others and the God-given opportunity. 2. Do Others Affirm This Direction? The second question to ask, then, after the subjective one of desire, is the more objective one of ability. Have I seen evidence, small as it may be at first, that I can meet the needs of others by working in this field? And, even more important than my own self-assessment, do others who love me, and seem to be honest with me, confirm this direction? Do they think I’d be a good fit for the kind of work I’m desiring? Here the subjective desires of our hearts meet the concrete, real-world, objective needs of others. Our vocational labors in this world, whether in Christian ministry or not, are not for existential release or our own private satisfaction, but for meeting the actual needs of others. “You may feel called, and others may affirm you, but you are not yet fully called until God opens a door.” Our desires have their part to play, but our true “calling” is not mainly shaped by our internal heart. It is shaped by the world outside of us. We so often hear “follow your heart” and “don’t settle for anything less than your dreams” in society, and even in the church. What’s most important, contrary to what the prevailing cultural word may be, is not bringing the desires of your heart to bear on the world, but letting the real-life needs of others shape your heart. In seeking God’s will for us vocationally, we look for where our developing aspirations match up with our developing abilities to meet the actual needs of others. Over time, we seek to cultivate a kind of dialogue (with ourselves and with others) between what we desire to do and what we find ourselves good at doing for the benefit of others. Delight in certain kinds of labor typically grows as others affirm our efforts, and we see them receiving genuine help. 3. What Doors Has God Opened? Finally, and perhaps the most overlooked and forgotten factor in the discussions on calling, is the actual God-given, real-world open door. You may feel called, and others may affirm your abilities, but you are not yet fully called until God opens a door. Here we glory in the truth of God’s providence, not just hypothetically but tangibly. The real world in which we live, and various options as they are presented to us, are not random or coincidental. God rules over all things — from him, through him, to him (Romans 11:36). And so as real-life options (job offers) are presented that fulfill an aspiration in us, and are confirmed by the company of others, we can take these as confirmation of God’s “calling.” Not that such a calling will never change. But for now, when your own personal sense of God’s leading, and good perspective and guidance from others, align with a real-world opportunity in the form of an actual job offer in front of you, you have a calling from God. “It is finally God, not man who provides the job offer.” And we can say this calling is from him because God himself, in his hand of providence, has done the decisive work. He started the process by planting in us righteous desires to help others; and he affirmed the direction through our lived-out abilities and the affirmation of friends. Now, he confirms that sense of calling by swinging open the right door at the right time. It is finally God, not man who provides the job offer. God not only makes overseers (Acts 20:28) and gives pastors (Ephesians 4:11–12) and sends out laborers into his global harvest (Matthew 9:37–38) and sends preachers (Romans 10:15) and sets wise managers over his household (Luke 12:42), but he makes dentists and plumbers. In his common kindness, he gives school teachers and entrepreneurs and social workers for the just and unjust. He sends executives and service workers. He gives you to the world in the service of others. Article by David Mathis