Others like thinking, fast and slow Features >>

Feel The Fear And Do It Anyway

Thinking For A Change

Think And Make Impact

The Principles And Power Of Vision

-160.webp)

The Principles And Power Of Vision (Keys To Achieving Personal And Corporate Destiny)

50 Mindful Steps To Self Esteem

Approval Addiction

How To Stop Worrying And Start Living

Sign Posts On The Road Of Success

Futureboards

About the Book

"Thinking, Fast and Slow" by Daniel Kahneman explores the two systems that drive the way we think: the fast, intuitive System 1 and the slow, deliberate System 2. Kahneman examines how these systems shape our judgments, decisions, and biases, shedding light on the inherent flaws in human cognition and offering insights on how to make better choices. The book explores various psychological phenomena and provides practical strategies for improving decision-making skills.

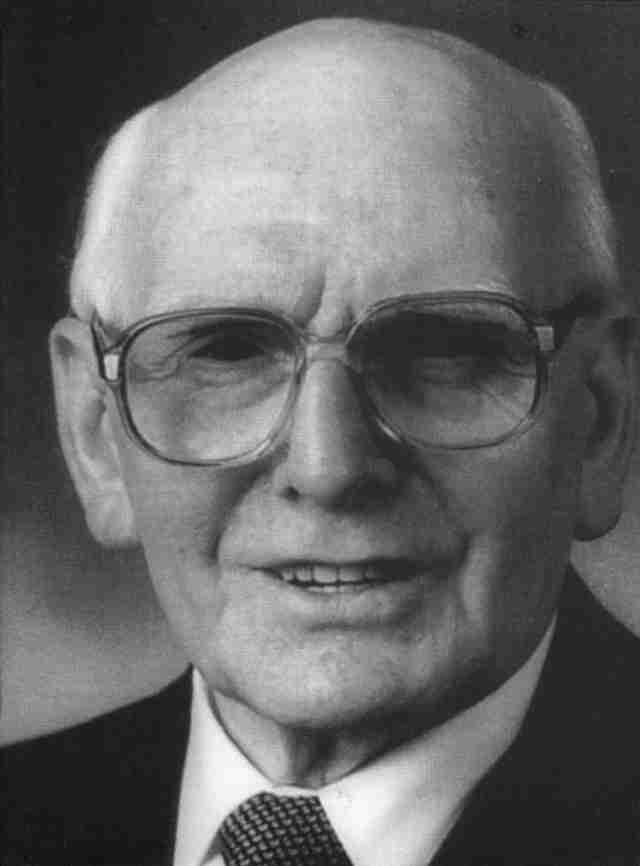

William Still

I recently read Dying to Live (Christian Focus, 1991), the autobiography of Scottish pastor William Still. I became interested in Still after reading his book The Work of the Pastor earlier this year.

The first half of Dying to Live tells about Still’s early years into young adulthood and his beginning in pastoral ministry. Still had an unsettled childhood. His parents were separated in his early years, and his father was an alcoholic. He was a sickly child who took refuge in music and became an accomplished pianist. He was part of the Salvation Army as a young man but then entered ministry in the Church of Scotland and served at the Gilcomston Church in his hometown of Aberdeen from 1945-1997.

The second half of the book deals with various aspects of Still’s pastoral ministry. Still was an evangelical. In his early ministry he worked with Billy Graham, Alan Redpath, and others in evangelistic events. With time, however, he moved away from what he came to call “evangelisticism” to develop a solid expositional ministry.

Still faced his fair share of hardships during the course of his ministry. When he moved away from pragmatic evangelistic methods, for example, more than two hundred people stopped attending his church almost overnight. In the preface, he references Martin Luther’s observation that there are three things which make a minister: study, prayer, and afflictions. He observes, “He who is not prepared to make enemies for Christ’s sake by the faithful preaching of the Word will never make lasting friends for Christ, either” (p. 93).

He describes one particularly difficult controversy early in his ministry when he confronted a group of disgruntled elders. At the end of one Sunday service, he read a statement confronting these men, which ended, “There you sit, with your heads down, guilty men. What would you say if I named you before the whole congregation? You stand condemned before God for your contempt of the Word and of his folk.” He adds, “The moment I had finished, I walked out of the pulpit. There was no last hymn—no benediction. I went right home. It was the hardest and most shocking thing I ever had to do in Gilcomston” (p. 124). That same week seven of his elders resigned and Still was called twice before his Presbytery to answer for the controversy. Yet, he endured.

Still maintains that in light of the unpleasantness one will face in the ministry that the minister of the Word must possess one quality in particular: “…I would say that this quality is courage: guts, sheer lion-hearted bravery, clarity of mind and purpose, grit. Weaklings are no use here. They have a place in the economy of God if they are not deliberate weaklings and stunted adults as Paul writes of both to the Romans and to the Corinthians. But weaklings are no use to go out and speak prophetically to men from God and declare with all compassion, as well as with faithfulness, the truth: the divine Word that cuts across all men’s worldly plans for their lives” (p. 140).

Still was a pioneer in several areas. First, he developed a pattern of preaching and teaching systematically through books of the Bible at a time when this was rarely done. He began a ministry of “consecutive Bible teaching” starting with the book of Galatians in 1947, calling this transition from “evangelisticism to systematic exposition … probably the most significant decision in my life” (p. 191).

He was also a pioneer in simplifying and integrating the ministry of the church. After noting how youth in the church were drifting away, even after extensive involvement in the church’s children’s ministry, Still writes, “I conceived the idea of ceasing all Sunday School after beginners and Primary age (seven years) and invited parents to have their children sit with them in the family pew from the age of eight” (p. 171). He laments “the disastrous dispersion of congregations by the common practice of segregating the church family into every conceivable category of division of ages, sexes, etc.” (p. 173).

Dying to Live is a helpful and encouraging work about the life and work of the minister and is to be commended to all engaged in the call of gospel ministry. As the title indicates, Still’s essential thesis is that in order to be effective in ministry the minister must suffer a series of deaths to himself (cf. John 12:24). On this he writes:

The deaths one dies before ministry can be of long duration—it can be hours and days before we minister, before the resurrection experience of anointed preaching. And then there is another death afterwards, sometimes worse than the death before. From the moment that you stand there dead in Christ and dead to everything you are and have and ever shall be and have, every breath you breathe thereafter, every thought you think, every word you say and deed you do, must be done over the top of your own corpse or reaching over it in your preaching to others. Then it can only be Jesus that comes over and no one else. And I believe that every preacher must bear the mark of that death. Your life must be signed by the Cross, not just Christ’s cross (and there is really no other) but your cross in his Cross, your particular and unique cross that no one ever died—the cross that no one ever could die but you and you alone: your death in Christ’s death (p. 136).

I recently read Dying to Live (Christian Focus, 1991), the autobiography of Scottish pastor William Still. I became interested in Still after reading his book The Work of the Pastor earlier this year.

The first half of Dying to Live tells about Still’s early years into young adulthood and his beginning in pastoral ministry. Still had an unsettled childhood. His parents were separated in his early years, and his father was an alcoholic. He was a sickly child who took refuge in music and became an accomplished pianist. He was part of the Salvation Army as a young man but then entered ministry in the Church of Scotland and served at the Gilcomston Church in his hometown of Aberdeen from 1945-1997.

The second half of the book deals with various aspects of Still’s pastoral ministry. Still was an evangelical. In his early ministry he worked with Billy Graham, Alan Redpath, and others in evangelistic events. With time, however, he moved away from what he came to call “evangelisticism” to develop a solid expositional ministry.

Still faced his fair share of hardships during the course of his ministry. When he moved away from pragmatic evangelistic methods, for example, more than two hundred people stopped attending his church almost overnight. In the preface, he references Martin Luther’s observation that there are three things which make a minister: study, prayer, and afflictions. He observes, “He who is not prepared to make enemies for Christ’s sake by the faithful preaching of the Word will never make lasting friends for Christ, either” (p. 93).

He describes one particularly difficult controversy early in his ministry when he confronted a group of disgruntled elders. At the end of one Sunday service, he read a statement confronting these men, which ended, “There you sit, with your heads down, guilty men. What would you say if I named you before the whole congregation? You stand condemned before God for your contempt of the Word and of his folk.” He adds, “The moment I had finished, I walked out of the pulpit. There was no last hymn—no benediction. I went right home. It was the hardest and most shocking thing I ever had to do in Gilcomston” (p. 124). That same week seven of his elders resigned and Still was called twice before his Presbytery to answer for the controversy. Yet, he endured.

Still maintains that in light of the unpleasantness one will face in the ministry that the minister of the Word must possess one quality in particular: “…I would say that this quality is courage: guts, sheer lion-hearted bravery, clarity of mind and purpose, grit. Weaklings are no use here. They have a place in the economy of God if they are not deliberate weaklings and stunted adults as Paul writes of both to the Romans and to the Corinthians. But weaklings are no use to go out and speak prophetically to men from God and declare with all compassion, as well as with faithfulness, the truth: the divine Word that cuts across all men’s worldly plans for their lives” (p. 140).

Still was a pioneer in several areas. First, he developed a pattern of preaching and teaching systematically through books of the Bible at a time when this was rarely done. He began a ministry of “consecutive Bible teaching” starting with the book of Galatians in 1947, calling this transition from “evangelisticism to systematic exposition … probably the most significant decision in my life” (p. 191).

He was also a pioneer in simplifying and integrating the ministry of the church. After noting how youth in the church were drifting away, even after extensive involvement in the church’s children’s ministry, Still writes, “I conceived the idea of ceasing all Sunday School after beginners and Primary age (seven years) and invited parents to have their children sit with them in the family pew from the age of eight” (p. 171). He laments “the disastrous dispersion of congregations by the common practice of segregating the church family into every conceivable category of division of ages, sexes, etc.” (p. 173).

Dying to Live is a helpful and encouraging work about the life and work of the minister and is to be commended to all engaged in the call of gospel ministry. As the title indicates, Still’s essential thesis is that in order to be effective in ministry the minister must suffer a series of deaths to himself (cf. John 12:24). On this he writes:

The deaths one dies before ministry can be of long duration—it can be hours and days before we minister, before the resurrection experience of anointed preaching. And then there is another death afterwards, sometimes worse than the death before. From the moment that you stand there dead in Christ and dead to everything you are and have and ever shall be and have, every breath you breathe thereafter, every thought you think, every word you say and deed you do, must be done over the top of your own corpse or reaching over it in your preaching to others. Then it can only be Jesus that comes over and no one else. And I believe that every preacher must bear the mark of that death. Your life must be signed by the Cross, not just Christ’s cross (and there is really no other) but your cross in his Cross, your particular and unique cross that no one ever died—the cross that no one ever could die but you and you alone: your death in Christ’s death (p. 136).

Suffering Under an All-Powerful Love

As I sat atop my lofted dorm-room bed and turned the page from Romans 8 to Romans 9 in my small, tattered Bible, I went from a chapter familiar enough to be easily skimmed to a chapter that I had no recollection of ever reading before. Both chapters emphasized the sovereignty of God — his sovereign love and his sovereign power. At 19 years old, I had not thought much about God’s sovereignty. I believed what I’d been taught as a child — that God was in control, that he knew every hair on my head, that he had the whole world in his hands. But I also believed that salvation was a choice I had made — that God chose me because he knew I’d someday choose him. When I entered college, however, the issue became inescapable. My college campus swirled with discussions about whether God elected people to salvation and whether he could know the future at all. Even my theology class was getting ready to host a debate between an Open Theist (someone who believes God doesn’t fully know the future until it happens) and a Calvinist (someone who believes God knows and ordains the future, including who will believe and be saved). It was only by chance that I had been reading Romans 8–9 the night before this debate. Or was it? God in Control That night, my beliefs began to change. I read of God’s relationship with his chosen people: Those whom he foreknew he also predestined to be conformed to the image of his Son, in order that he might be the firstborn among many brothers. And those whom he predestined he also called, and those whom he called he also justified, and those whom he justified he also glorified. (Romans 8:29–30) Could it possibly be true that this foreknowing, predestining God didn’t know the future? It could not. Or was it conceivable that the God who said, “It depends not on human will or exertion, but on God, who has mercy,” was merely looking ahead in the future to see who would and wouldn’t choose him (Romans 9:16)? It was not. And furthermore, God declared that he was working all things together for the good of those he’d called (Romans 8:28). Could God work all things together for good if all things were not genuinely under his control? My 19-year-old heart began to swell with joy and relief. This God was not back on his heels, trying to figure out what to do, nor was he waiting for me to figure him out. He was bringing his good plans to pass. He called me, he saved me, and he would keep me in every circumstance. Does God’s Goodness Miscarry? My understanding of God’s sovereign grace grew as my knowledge of God’s word grew. And I loved his sovereignty — in theory at least. I loved that my God was so powerful and big and in charge. When I saw others go through difficult circumstances, I sympathized with them, but I also had a settled sense that God had a plan born from his love. It wasn’t until I was up against my own difficult circumstance that the thought flashed in my mind: perhaps God was working something not good in my life. As a young wife and mom, I never considered the possibility of miscarrying. So when it happened, I was shocked that my own womb could become a place of death. All I knew of God flooded my mind, almost as a reproach. As I faced the loss of our little one, I wasn’t tempted to doubt his power but his love. I knew he could have kept our baby alive, so why didn’t he? Yet Romans 8 was there to keep me grounded, reminding me that not even death could separate us from his love. Paul’s words were an anchor: I am sure that neither death nor life, nor angels nor rulers, nor things present nor things to come, nor powers, nor height nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord. (Romans 8:38–39) As the years rolled on, God’s sovereignty over all things was the buoy that kept me afloat in every season. I was learning to trust God’s love as he carried us through job loss, babies received and one lost, moves, and new ministry. Yet it was the birth of our youngest son that brought the deepest challenge to my trust in God’s power and plans. With our son’s arrival, we faced uncertainty regarding his future, a future that, in the best case, would involve disability and health difficulties. During the chronic trials that ensued, including our son’s sleep disorder, seizures, and eating difficulties that involved years of almost daily vomit, a different sort of temptation occasionally crept in — the thought that God might love us, but he maybe couldn’t help us. Night after night after night, year after year after year, we would pray for relief. But relief didn’t come. Different Sort of Power I was looking for God’s power to come in the form of physical relief from our trials. I was tired and worn. I wanted to be free of the difficulties of nighttime G-tube feedings and regular vomit clean-up. If God answered those prayers, I reasoned, that would be a sign of his power. Yet which is more difficult: to change someone’s circumstances from hard to easy, or to change the person in the circumstances from floundering to flourishing despite it all? Would God have shown more of his sovereign power if he had put down all his enemies once and for all, preventing the cross and the resurrection? Or is God’s power more greatly displayed through his planning from before time to crush his Son, defeat sin, and then raise his Son from the dead, so that he could make his enemies his friends? Any tyrant with a large army can squelch his enemies, but only our gracious and powerful God turns enemies into sons through the folly of the cross and the empty tomb. As Paul testifies, God often manifests his power through our weaknesses. It was Paul’s thorn in the flesh that occasioned God’s sovereign power resting upon him: I will boast all the more gladly of my weaknesses, so that the power of Christ may rest upon me. For the sake of Christ, then, I am content with weaknesses, insults, hardships, persecutions, and calamities. For when I am weak, then I am strong. (2 Corinthians 12:9–10) “The sovereign power of God rests on his people, not to remove their thorns, but to teach them of a stronger power.” In a world where almost everyone seems obsessed with power — whether they have it, how they can get it — God’s word shows us the deeper power: the power of his Spirit. God’s power is ours when we entrust ourselves to him amid weakness. We need not demand power from the world. We need not seek position or platform. The sovereign power of God rests on his people, not to remove their thorns, but to teach them of a stronger power — the power of God that contents us with trials, so long as we have Christ’s Spirit. No Trite Slogan All those years ago as a college sophomore, Romans 8 and 9 showed me the sovereign love and sovereign power of God. In Romans 9, I met a God to whom back talk was not permitted: You will say to me then, “Why does he still find fault? For who can resist his will?” But who are you, O man, to answer back to God? Will what is molded say to its molder, “Why have you made me like this?” (Romans 9:19–20) In Romans 8, that same fearfully powerful God was also utterly committed to my good in all things, so much so, that his Spirit intercedes for me as he works on my behalf (Romans 8:26–28). Some believe that Romans 8:28 is a trite way to comfort the afflicted — that it shuts up the grief of the hurting, as though telling a suffering saint that God is working their hardship for good makes a mockery of the pain. As we are imperfect people, we should consider that possibility. But for me, no truth is as precious. “God is good. God is strong. Not one thing happens to us apart from his perfect plan.” Knowing that God is working all things for my good has been the dearest and deepest comfort, even, and especially, in the darkest of seasons. God is working all things for my good when our son is in the hospital (again), or when my husband is dealing with chronic pain (still), or when betrayal and slander touch my life or the lives of those I love. It’s a reality that keeps my heart whole even as it’s breaking, and my mind clear even in the fog of confusion. He is good. He is strong. Not one thing happens to us apart from his perfect plan. God’s sovereign love and power mean that we can trust him — now and forever. Article by Abigail Dodds Regular Contributor