Others like the story of marriage Features >>

The Meaning Of Marriage: A Couple’s Devotional

Healing Your Marriage When Trust Is Broken

-160.webp)

Building Stronger Marriages And Families

The Intimate Marriage - A Practical Guide To Building A Great Marriage

The Act Of Marriage

The Marriage Builder

A Ceremony Of Marriage

The Meaning Of Marriage

The 4 Seasons Of Marriage

Your Marriage And Your Ancestry

About the Book

"The Story of Marriage" by John and Lisa Bevere explores the biblical definition and purpose of marriage, offering practical advice and insights for creating a strong and lasting relationship. The book discusses the roles and responsibilities of husbands and wives, the importance of communication and intimacy, and how to navigate challenges in marriage with grace and love. Overall, it emphasizes the significance of honoring God in marriage and building a foundation of faith and commitment.

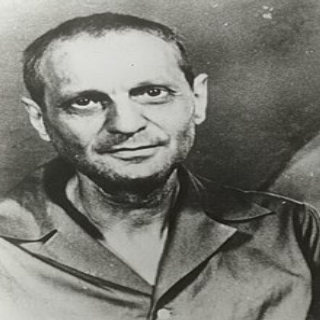

Richard Wurmbrand

Richard Wurmbrand (1909 – 2001) was born in 1909 in Bucharist in the country of Romania. He was the youngest of four boys born in a Jewish family. He lived with his family in Istanbul for a short time. When he was 9, his father died and the Wurmbrands returned to Romania when he was 15.

He was sent to study Marxism in Moscow. When he returned, he was already a Comintern Agent. A Comintern Agent was a member of the Communist International Organisation which intended to fight:

Like other Romanian Communists, he was arrested and released several times.

He married Sabina Oster on 26th October 1936. Wurmbrand and his wife went to live in an isolated village high in the mountains of Romania. But, as a athiest there was no peace to be found in his heart. So one day, when his heart was in a state of turmoil he cried out:

“God, if perchance you exist, it is Your duty to reveal yourself to me.”

Shorthly after he prayed that prayer, he met a German carpenter in his village who gave him a bible. The carpenter and his wife had been praying earnestly that God would bring a Jew to his village, because the carpenter wanted to bring a Jew to Christ, because Jesus was a Jew. So the carpenter gave him a Bible to read. Wurmbrand said, when he opened that Bible he could not stop weeping. He had read the Bible before but it had meant nothing to him. This time when he opened the Bible he could barely read it because of the copious amount of tears that filled his eyes. Sometime later he found out the carpenter and his wife had been praying earnestly for him. Wurnbrand said that every word that he read were like flames of love burning in his heart. He realized for the first ime in his life that there was a God of love who loved him, even though he had beeen living a bad life and had nurtured a hated towards the concept of a ‘loving’ God.

The Power of Intercessory Prayer

But now for the first time he knew that Jesus had suffered at the cross of Calvary for his sins and he was loved and accepted of God. Richard and his wife became believers in Jesus the Messiah. All the hatred that he had formerly held toward God was washed away under the blood of Christ and Richard and his wife Sabrina were born of the Spirit. That is the power of intercessory prayer!

Richard prepared himself for the ministry. He was ordained as an Anglican minister in 1938 at the start of world war 2. Both Richard and his wife were arrested several times. They were beaten and hauled before a Nazi court. They suffered under the Nazi regime throughout world war 2. But Richard said, it was only a taste of what was to come.

Russian Troups Enter Romania

Towards the end of world war 2, Richard Wurmbrand became a Lutheran and he pastored a Lutheran church in Romania. But, the same year, 1 million Russian troups entered and occupied the entire territory of Romania.

Within a very short space of time the Communists took over Romania. The reign of terror began. Out of fear 4,000 priests, pastors & ministers became Communists overnight. They confessed their allegience and loyalty to the new Communist Government because they all feared for their survival.

Romania’s Resistance

Harsh persecutions of any enemies of the Communist government started with the Soviet occupation in 1945. The Soviet army behaved as an occupation force (although theoretically it was an ally against Nazi Germany), and could arrest virtually anyone at will. Shortly after Soviet occupation, ethnic Germans (who were Romanian citizens and had been living as a community in Romania for 800 years) were deported to the Donbas coal mines. Despite the King’s protest, who pointed out that this was against international law, an estimated 70,000 men and women were forced to leave their homes, starting in January 1945, before the war had even ended. They were loaded in cattle cars and put to work in the Soviet mines for up to ten years as “reparations”, where about one in five died from disease, accidents and malnutrition.

Once the Communist government became more entrenched, the number of arrests increased. All strata of society were involved, but particularly targeted were the pre-war elites, such as intellectuals, clerics, teachers, former politicians (even if they had left-leaning views) and anybody who could potentially form the nucleus of anti-Communist resistance. The existing prisons were filled with political prisoners, and a new system of forced labor camps and prisons was created, modeled after the Soviet Gulag. Some of the most notorious prisons included Sighet, Gherla, Piteşti and Aiud, and forced labor camps were set up at lead mines and in the Danube Delta.

Underground Church

Richard and his wife knew that Christianity and Communism were totally opposed to each other. They knew that a true follower of Christ cannot compromise. So they created an “Underground Church” movement to preach the pure gospel of Christ and to reach out to the unsaved people of Romania and secondly to reach out secretly to the Russian soldiers. They secretly printed thousands of Bibles and Christian literature and distributed it to the Russian soldiers. Many of the Russian soldiers were convicted and they gave their life to Christ.

So the underground church grew. But, in 1948 the Secret Police arrested Wurmbrand and he was placed in solitary confinement for 3 years. He was then transferred to a group cell for the next five years. Whilst in prison he continued to win the other prisoners to Christ. After 8 years in prison he was released and he immediately resumed his work with the undergound church. A few years later, 1959, he was arrested again and was sentenced to 25 years in prison. However, after spending 5 years in prison an organisation called the Christian Alliance negotiated with the Communist Government and they managed to secure his release for a fee of $10,000. They quickly got Richard Wurmbrand out of Romania and took him to England, then to the USA.

In 1966, Richard was called to Washington DC to give his testimony before the United States Senate. He took off his shirt to show the Senate the scars and the wounds that he received whilst he served time in prison under the Communist Government in Romania.

The newspapers throughout the USA, Europe and Asia carried his story all across the world. Christian leaders called him the “Voice of the Underground Church.”

In 1967, with a $100 old typewriter and 500 names and addresses, Richard Wurmbrand published the first issue of THE VOICE OF THE MARTYRS newsletter. This newsletter was dedicated to communicating the testimonies and trails facing our brothers and sisters in restricted nations worldwide. Richard wrote:

“The message I bring from the Underground Church is:

“Don’t abandon us!”

“Don’t forget us!”

“Don’t write us off!”

“Give us the tools we need! We will pay the price for using them!”

“This is the message I have been charged to deliver to the free church.”

Richard Wurmbrand and his wife travelled throughout the world to establish a network of over 30 offices. Their primary aim was to call Christians to shoulder their responsibility and to demonstrate the real substance of their faith by supporting their brothers and sisters in Christ who are being persecuted in heathen lands.

The VOICE OF THE MARTYRS newsletter continues to inform, and lead to action, Christians throughout the free world of the plight of those who suffer for their faith in Jesus Christ. Throughout their network of offices around the world, the newsletter is published in over 30 different languages. To this cause, VOICE OF THE MARTYRS presses on, serving in nearly 40 countries around the world where our brothers and sisters are systematically persecuted.

The writer of the Book of Hebrews brings a convicting word to the Christian church:

” Remember them that are in bonds, as bound with them; and them that suffer adversity, as being yourselves also in the body.”

(Hebrews 13:3)

We have a responsibility to those who suffer for their faith in Christ.

Today, there is an estimated 200 million Christians in heathen nations who are suffering persecution for their faith in Christ.

Richard Wurmbrand (1909 – 2001) was born in 1909 in Bucharist in the country of Romania. He was the youngest of four boys born in a Jewish family. He lived with his family in Istanbul for a short time. When he was 9, his father died and the Wurmbrands returned to Romania when he was 15.

He was sent to study Marxism in Moscow. When he returned, he was already a Comintern Agent. A Comintern Agent was a member of the Communist International Organisation which intended to fight:

Like other Romanian Communists, he was arrested and released several times.

He married Sabina Oster on 26th October 1936. Wurmbrand and his wife went to live in an isolated village high in the mountains of Romania. But, as a athiest there was no peace to be found in his heart. So one day, when his heart was in a state of turmoil he cried out:

“God, if perchance you exist, it is Your duty to reveal yourself to me.”

Shorthly after he prayed that prayer, he met a German carpenter in his village who gave him a bible. The carpenter and his wife had been praying earnestly that God would bring a Jew to his village, because the carpenter wanted to bring a Jew to Christ, because Jesus was a Jew. So the carpenter gave him a Bible to read. Wurmbrand said, when he opened that Bible he could not stop weeping. He had read the Bible before but it had meant nothing to him. This time when he opened the Bible he could barely read it because of the copious amount of tears that filled his eyes. Sometime later he found out the carpenter and his wife had been praying earnestly for him. Wurnbrand said that every word that he read were like flames of love burning in his heart. He realized for the first ime in his life that there was a God of love who loved him, even though he had beeen living a bad life and had nurtured a hated towards the concept of a ‘loving’ God.

The Power of Intercessory Prayer

But now for the first time he knew that Jesus had suffered at the cross of Calvary for his sins and he was loved and accepted of God. Richard and his wife became believers in Jesus the Messiah. All the hatred that he had formerly held toward God was washed away under the blood of Christ and Richard and his wife Sabrina were born of the Spirit. That is the power of intercessory prayer!

Richard prepared himself for the ministry. He was ordained as an Anglican minister in 1938 at the start of world war 2. Both Richard and his wife were arrested several times. They were beaten and hauled before a Nazi court. They suffered under the Nazi regime throughout world war 2. But Richard said, it was only a taste of what was to come.

Russian Troups Enter Romania

Towards the end of world war 2, Richard Wurmbrand became a Lutheran and he pastored a Lutheran church in Romania. But, the same year, 1 million Russian troups entered and occupied the entire territory of Romania.

Within a very short space of time the Communists took over Romania. The reign of terror began. Out of fear 4,000 priests, pastors & ministers became Communists overnight. They confessed their allegience and loyalty to the new Communist Government because they all feared for their survival.

Romania’s Resistance

Harsh persecutions of any enemies of the Communist government started with the Soviet occupation in 1945. The Soviet army behaved as an occupation force (although theoretically it was an ally against Nazi Germany), and could arrest virtually anyone at will. Shortly after Soviet occupation, ethnic Germans (who were Romanian citizens and had been living as a community in Romania for 800 years) were deported to the Donbas coal mines. Despite the King’s protest, who pointed out that this was against international law, an estimated 70,000 men and women were forced to leave their homes, starting in January 1945, before the war had even ended. They were loaded in cattle cars and put to work in the Soviet mines for up to ten years as “reparations”, where about one in five died from disease, accidents and malnutrition.

Once the Communist government became more entrenched, the number of arrests increased. All strata of society were involved, but particularly targeted were the pre-war elites, such as intellectuals, clerics, teachers, former politicians (even if they had left-leaning views) and anybody who could potentially form the nucleus of anti-Communist resistance. The existing prisons were filled with political prisoners, and a new system of forced labor camps and prisons was created, modeled after the Soviet Gulag. Some of the most notorious prisons included Sighet, Gherla, Piteşti and Aiud, and forced labor camps were set up at lead mines and in the Danube Delta.

Underground Church

Richard and his wife knew that Christianity and Communism were totally opposed to each other. They knew that a true follower of Christ cannot compromise. So they created an “Underground Church” movement to preach the pure gospel of Christ and to reach out to the unsaved people of Romania and secondly to reach out secretly to the Russian soldiers. They secretly printed thousands of Bibles and Christian literature and distributed it to the Russian soldiers. Many of the Russian soldiers were convicted and they gave their life to Christ.

So the underground church grew. But, in 1948 the Secret Police arrested Wurmbrand and he was placed in solitary confinement for 3 years. He was then transferred to a group cell for the next five years. Whilst in prison he continued to win the other prisoners to Christ. After 8 years in prison he was released and he immediately resumed his work with the undergound church. A few years later, 1959, he was arrested again and was sentenced to 25 years in prison. However, after spending 5 years in prison an organisation called the Christian Alliance negotiated with the Communist Government and they managed to secure his release for a fee of $10,000. They quickly got Richard Wurmbrand out of Romania and took him to England, then to the USA.

In 1966, Richard was called to Washington DC to give his testimony before the United States Senate. He took off his shirt to show the Senate the scars and the wounds that he received whilst he served time in prison under the Communist Government in Romania.

The newspapers throughout the USA, Europe and Asia carried his story all across the world. Christian leaders called him the “Voice of the Underground Church.”

In 1967, with a $100 old typewriter and 500 names and addresses, Richard Wurmbrand published the first issue of THE VOICE OF THE MARTYRS newsletter. This newsletter was dedicated to communicating the testimonies and trails facing our brothers and sisters in restricted nations worldwide. Richard wrote:

“The message I bring from the Underground Church is:

“Don’t abandon us!”

“Don’t forget us!”

“Don’t write us off!”

“Give us the tools we need! We will pay the price for using them!”

“This is the message I have been charged to deliver to the free church.”

Richard Wurmbrand and his wife travelled throughout the world to establish a network of over 30 offices. Their primary aim was to call Christians to shoulder their responsibility and to demonstrate the real substance of their faith by supporting their brothers and sisters in Christ who are being persecuted in heathen lands.

The VOICE OF THE MARTYRS newsletter continues to inform, and lead to action, Christians throughout the free world of the plight of those who suffer for their faith in Jesus Christ. Throughout their network of offices around the world, the newsletter is published in over 30 different languages. To this cause, VOICE OF THE MARTYRS presses on, serving in nearly 40 countries around the world where our brothers and sisters are systematically persecuted.

The writer of the Book of Hebrews brings a convicting word to the Christian church:

” Remember them that are in bonds, as bound with them; and them that suffer adversity, as being yourselves also in the body.”

(Hebrews 13:3)

We have a responsibility to those who suffer for their faith in Christ.

Today, there is an estimated 200 million Christians in heathen nations who are suffering persecution for their faith in Christ.

witnessing with gospel tracts

Gospel tracts and pamphlets are very important tools in evangelism. The printing press was a wonderful gift from God and has been used greatly for the glory of Jesus Christ. The printed page can greatly multiply our efforts in the service of the Lord and tracts can oftentimes go places where we cannot go. Be Careful About the Message The first consideration in the use of Gospel tracts is to be certain that the content is scriptural. There are three problems with many gospel tracts: 1. Many tracts do not contain a clear and biblical presentation of the gospel. Many refer to salvation in an unscriptural and confusing manner, such as "asking Jesus into my heart" or "giving my life to Christ." Salvation is not to give one's life to Christ, but is to trust the finished atonement of Christ. Nowhere in the New Testament do we see the Lord Jesus or the Apostles telling people to give their lives to Christ or to ask Jesus into their hearts. We need to follow the Bible very carefully in the terminology we use so that people are not confused and so they do not make false professions of faith. 2. The second serious drawback is that most tracts do not deal with repentance. Most don't even mention the word or even hint at the concept, yet the Lord Jesus Christ and His apostles preached repentance plainly and demanded it from those who would be saved. Salvation only comes by "repentance toward God, and faith toward our Lord Jesus Christ" (Acts 20:21). Any presentation of the gospel should include the fact that God "now commandeth all men every where to repent" (Acts 17:30). Whether or not the word "repentance" is used in a gospel tract, the idea should be. What is repentance? It is a turning, a change of direction (1 Thess. 1:9). When I receive Jesus Christ as my Lord and Savior, I am turning my back to the old life. 3. Another problem is that many simply do not give enough information. Large numbers of people in North America today are as ignorant of the true God of the Bible and of the basics of the Gospel of the Lord Jesus Christ as any Hindu in darkest Asia. It is crucial that we begin with the basics with these people, and that we explain biblical terms thoroughly, otherwise, when they hear terms such as "saved," "believe," "Christ," "God," "sin," they won't have the proper idea of what we are talking about, and any "profession" they make will be empty. The following are a few examples of gospel tracts that include repentance: "The Bridge to Eternal Life." This full-color pamphlet is also illustrated. [Detroit Baptist Theological Seminary, Majestic Media, 810-725-5800] "Have You Considered This?" [Dennis Costella, Fundamental Evangelistic Association, 1476 W. Herndon, Suite 104 Fresno, CA 93711, 559-438-0080. [Also available online at https://www.feasite.org/Tracts/fbconsdr.htm] "I'm a Pretty Good Person" is one of the many tracts published by the Fellowship Tract League. It is a good tract to show people that their good works and religion won't take them to heaven. [available from Sermon and Song Ministries, P.O. Box 109, Ravenna, OH 44266, www.sermonandsong.org; also available from Fellowship Tract League, P.O. Box 164, Lebanon, OH 45036, 513-494-1075, http://www.fellowshiptractleague.org/] "The Little Red Book." This 12-page pamphlet is illustrated and has been effective. [Little Red Book, P.O. Box 341, N. Greece, NY 14515 or P.O. Box 7195, Greensboro, NC 27417, LRB@frontiernet.net, 585-225-0715] "The Most Important Thing You Must Consider." This tract is strong on God's holiness and just punishment of sin and the necessity of repentance. [Faith Baptist Church, 105-01 37th Avenue, Corona, NY 11368 718-457-5651, http://www.studygodsword.com/fbcpress/tracts.html] "What Is Your Life?" This pamphlet is illustrated. [Operation Somebody Cares, 1131 Brentwood Drive, Collinsville, VA 24078, 276-647-5328, http://www.operationsomebodycares.com] "What Must I Do to Be Saved" by the late Evangelist John R. Rice. [Sword of the Lord, Box 1099, Murfreesboro, TN 37130. 800-247-9673, booksales@swordofthelord.com] "Why Should I Let You into My Heaven?" [Dean Myers, deanmyers2@juno.com] Liberty Baptist Church in Greenville, Michigan, has a wide range of helpful Gospel tracts. [Pastor Mike Austin, Liberty Baptist Church, 11845 W. Carson City Road, Greenville, MI 48838. 616-754-7151, pastor@libertygospeltracts.com, http://www.libertygospeltracts.com/] Mercy and Truth Ministries has some interesting small tracts. One is titled "You Can Get to Heaven from ---------" and an edition can be obtained for each state in the U.S. [Mercy and Truth Ministries, Lawrence, KS 66049, 875-887-2203] Pilgrim Fundamental Baptist Press publishes a tract that is designed to leave with a tip after a meal. On the outside it says, "Thank you and here are 2 tips for you!" On the inside it states that Tip #1 is a monetary token of appreciation for your service, and Tip #2 is a Gospel tract that explains how to be saved. It is large enough to hold a standard tract. [Pilgrim Fundamental Baptist Press, P.O. Box 1832, Elkton, MD 21922] Things to Remember When Passing Out Tracts Giving out tracts is something every born again believer can do, young or old. 1. Remember that it is each believer's responsibility to give out the gospel (see Matt. 28:19-20; Mk. 16:15; Luke 24:45-48; Acts 1:8; 2 Cor. 5:17-21; Phil. 2:16; 2 Tim. 4:5). 2. Remember that by giving out the gospel you are offering the greatest gift in the world. When we give out the gospel we are offering dead people life; we are offering poor people riches; we are offering sick people healing; we are offering lost people salvation. 3. It is wise to read the tracts first yourself before giving them out to others. This way you will know exactly what it says and you can refer to it when you talk to people. Also, by first reading tracts before giving them away you can see if the tract contains something that is not true or leaves out something important such as repentance. 4. Make a commitment to give out so many tracts each week. 5. Always be pleasant and polite. Remember that you are a complete stranger to the people you are approaching. Ask kindly, "May I give you something special to read?" or "I have some Good News for You" or "May I give you something that has been a blessing in my own life?" If they are busy ask them to put it in their pocket and read at home. 6. Keep in mind that the goal is not merely to give out tracts but to find opportunities to witness to people about the Lord Jesus Christ with the goal of leading them to salvation. Use the tracts to open the conversation, and when you find someone who is interested take the time to talk further with him and see if he or she is willing to meet again. We must remember that it is not enough to give out tracts; the objective is to see people come to Christ and baptized and discipled (Matt. 28:19-20). 7. Don't get upset or discouraged if someone says something against Jesus and the Bible or they mock you and what you are doing. "For unto you it is given in the behalf of Christ, not only to believe on him, but also to suffer for his sake" (Phil. 1:29; see also Matt. 5:11-12; Jn. 15:20; Luke 9:26). 8. Give out tracts to those who look like they might be interested and to those who don't. We cannot look upon the hearts of men and we cannot know who God might be dealing with. Jesus said preach the gospel to every creature (Mk. 16:15). "In the morning sow thy seed, and in the evening withhold not thine hand: for thou knowest not whether shall prosper, either this or that, or whether they both shall be alike good" (Ecc. 11:6). Ecclesiastes 11:1 says, "Cast thy bread upon the waters: for thou shalt find it after many days." This refers to the custom of casting seed on the marshy ground after a river such as the Nile had overflowed its banks, trusting that the seed will take root and bring forth a crop. "When the waters receded, the grain in the alluvial soil sprang up. 'Waters' express the seemingly hopeless character of the recipients of the charity; but it shall prove at last to have been not thrown away" (Jamieson, Fausset, Brown). 9. Be sure there is a name and address stamped on each tract so that if someone is interested they have a contact for further help. A gospel correspondence course is a good way to follow up on tract distribution. See the section on correspondence courses in our book "Ideas for Evangelism" for suggestions. This seems to be more effective in some places than others, but we have personally seen much fruit by this means. 10. One of the most important things about tract distribution is faithfulness and persistence. Some may be thrown away but others may find them. We have a man in our church who first got interested in Christ by reading a tract that was given to his friend. This has happened many times. God wants faithful workers. Don't get discouraged if nothing seems to be happening. We must do this work by faith, not by sight. Keep your eyes on the Lord and trust Him to accomplish His will and to give fruit and just continue to give out the gospel. "But this I say, He which soweth sparingly shall reap also sparingly; and he which soweth bountifully shall reap also bountifully" (2 Cor. 9:6). "Moreover it is required in stewards, that a man be found faithful" (1 Cor. 4:2). 11. Remember that our real enemy in tract distribution is not people, but the devil. He is the god of this world who is blinding the minds of the unbelievers (2 Cor. 4:4). Thus we must have on the whole armor of God as we go about this important work (Eph. 6:11-12). 12. Pray much for your tract distribution, both before and after. Pray that God will open the eyes of the people so that they desire to know Him and that they will read and understand the tracts. Updated July 21, 2008. First published January 15, 1998 by David Cloud, Fundamental Baptist Information Service, P.O. Box 610368, Port Huron, MI 48061. Used with permission.