-480.webp)

The Cross And The Switchblade: A True Story Order Printed Copy

- Author: David Wilkerson

- Size: 972KB | 171 pages

- |

Others like the cross and the switchblade: a true story Features >>

About the Book

"The Cross and the Switchblade" is a true story about a young pastor, David Wilkerson, who is called by God to work with troubled gang members in New York City. Through his faith and determination, Wilkerson is able to reach out to these young men and help change their lives for the better. The book highlights the power of faith, love, and compassion in overcoming obstacles and making a positive impact in the world.

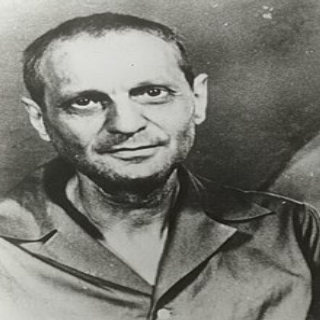

Richard Wurmbrand

Richard Wurmbrand (1909 – 2001) was born in 1909 in Bucharist in the country of Romania. He was the youngest of four boys born in a Jewish family. He lived with his family in Istanbul for a short time. When he was 9, his father died and the Wurmbrands returned to Romania when he was 15.

He was sent to study Marxism in Moscow. When he returned, he was already a Comintern Agent. A Comintern Agent was a member of the Communist International Organisation which intended to fight:

Like other Romanian Communists, he was arrested and released several times.

He married Sabina Oster on 26th October 1936. Wurmbrand and his wife went to live in an isolated village high in the mountains of Romania. But, as a athiest there was no peace to be found in his heart. So one day, when his heart was in a state of turmoil he cried out:

“God, if perchance you exist, it is Your duty to reveal yourself to me.”

Shorthly after he prayed that prayer, he met a German carpenter in his village who gave him a bible. The carpenter and his wife had been praying earnestly that God would bring a Jew to his village, because the carpenter wanted to bring a Jew to Christ, because Jesus was a Jew. So the carpenter gave him a Bible to read. Wurmbrand said, when he opened that Bible he could not stop weeping. He had read the Bible before but it had meant nothing to him. This time when he opened the Bible he could barely read it because of the copious amount of tears that filled his eyes. Sometime later he found out the carpenter and his wife had been praying earnestly for him. Wurnbrand said that every word that he read were like flames of love burning in his heart. He realized for the first ime in his life that there was a God of love who loved him, even though he had beeen living a bad life and had nurtured a hated towards the concept of a ‘loving’ God.

The Power of Intercessory Prayer

But now for the first time he knew that Jesus had suffered at the cross of Calvary for his sins and he was loved and accepted of God. Richard and his wife became believers in Jesus the Messiah. All the hatred that he had formerly held toward God was washed away under the blood of Christ and Richard and his wife Sabrina were born of the Spirit. That is the power of intercessory prayer!

Richard prepared himself for the ministry. He was ordained as an Anglican minister in 1938 at the start of world war 2. Both Richard and his wife were arrested several times. They were beaten and hauled before a Nazi court. They suffered under the Nazi regime throughout world war 2. But Richard said, it was only a taste of what was to come.

Russian Troups Enter Romania

Towards the end of world war 2, Richard Wurmbrand became a Lutheran and he pastored a Lutheran church in Romania. But, the same year, 1 million Russian troups entered and occupied the entire territory of Romania.

Within a very short space of time the Communists took over Romania. The reign of terror began. Out of fear 4,000 priests, pastors & ministers became Communists overnight. They confessed their allegience and loyalty to the new Communist Government because they all feared for their survival.

Romania’s Resistance

Harsh persecutions of any enemies of the Communist government started with the Soviet occupation in 1945. The Soviet army behaved as an occupation force (although theoretically it was an ally against Nazi Germany), and could arrest virtually anyone at will. Shortly after Soviet occupation, ethnic Germans (who were Romanian citizens and had been living as a community in Romania for 800 years) were deported to the Donbas coal mines. Despite the King’s protest, who pointed out that this was against international law, an estimated 70,000 men and women were forced to leave their homes, starting in January 1945, before the war had even ended. They were loaded in cattle cars and put to work in the Soviet mines for up to ten years as “reparations”, where about one in five died from disease, accidents and malnutrition.

Once the Communist government became more entrenched, the number of arrests increased. All strata of society were involved, but particularly targeted were the pre-war elites, such as intellectuals, clerics, teachers, former politicians (even if they had left-leaning views) and anybody who could potentially form the nucleus of anti-Communist resistance. The existing prisons were filled with political prisoners, and a new system of forced labor camps and prisons was created, modeled after the Soviet Gulag. Some of the most notorious prisons included Sighet, Gherla, Piteşti and Aiud, and forced labor camps were set up at lead mines and in the Danube Delta.

Underground Church

Richard and his wife knew that Christianity and Communism were totally opposed to each other. They knew that a true follower of Christ cannot compromise. So they created an “Underground Church” movement to preach the pure gospel of Christ and to reach out to the unsaved people of Romania and secondly to reach out secretly to the Russian soldiers. They secretly printed thousands of Bibles and Christian literature and distributed it to the Russian soldiers. Many of the Russian soldiers were convicted and they gave their life to Christ.

So the underground church grew. But, in 1948 the Secret Police arrested Wurmbrand and he was placed in solitary confinement for 3 years. He was then transferred to a group cell for the next five years. Whilst in prison he continued to win the other prisoners to Christ. After 8 years in prison he was released and he immediately resumed his work with the undergound church. A few years later, 1959, he was arrested again and was sentenced to 25 years in prison. However, after spending 5 years in prison an organisation called the Christian Alliance negotiated with the Communist Government and they managed to secure his release for a fee of $10,000. They quickly got Richard Wurmbrand out of Romania and took him to England, then to the USA.

In 1966, Richard was called to Washington DC to give his testimony before the United States Senate. He took off his shirt to show the Senate the scars and the wounds that he received whilst he served time in prison under the Communist Government in Romania.

The newspapers throughout the USA, Europe and Asia carried his story all across the world. Christian leaders called him the “Voice of the Underground Church.”

In 1967, with a $100 old typewriter and 500 names and addresses, Richard Wurmbrand published the first issue of THE VOICE OF THE MARTYRS newsletter. This newsletter was dedicated to communicating the testimonies and trails facing our brothers and sisters in restricted nations worldwide. Richard wrote:

“The message I bring from the Underground Church is:

“Don’t abandon us!”

“Don’t forget us!”

“Don’t write us off!”

“Give us the tools we need! We will pay the price for using them!”

“This is the message I have been charged to deliver to the free church.”

Richard Wurmbrand and his wife travelled throughout the world to establish a network of over 30 offices. Their primary aim was to call Christians to shoulder their responsibility and to demonstrate the real substance of their faith by supporting their brothers and sisters in Christ who are being persecuted in heathen lands.

The VOICE OF THE MARTYRS newsletter continues to inform, and lead to action, Christians throughout the free world of the plight of those who suffer for their faith in Jesus Christ. Throughout their network of offices around the world, the newsletter is published in over 30 different languages. To this cause, VOICE OF THE MARTYRS presses on, serving in nearly 40 countries around the world where our brothers and sisters are systematically persecuted.

The writer of the Book of Hebrews brings a convicting word to the Christian church:

” Remember them that are in bonds, as bound with them; and them that suffer adversity, as being yourselves also in the body.”

(Hebrews 13:3)

We have a responsibility to those who suffer for their faith in Christ.

Today, there is an estimated 200 million Christians in heathen nations who are suffering persecution for their faith in Christ.

Richard Wurmbrand (1909 – 2001) was born in 1909 in Bucharist in the country of Romania. He was the youngest of four boys born in a Jewish family. He lived with his family in Istanbul for a short time. When he was 9, his father died and the Wurmbrands returned to Romania when he was 15.

He was sent to study Marxism in Moscow. When he returned, he was already a Comintern Agent. A Comintern Agent was a member of the Communist International Organisation which intended to fight:

Like other Romanian Communists, he was arrested and released several times.

He married Sabina Oster on 26th October 1936. Wurmbrand and his wife went to live in an isolated village high in the mountains of Romania. But, as a athiest there was no peace to be found in his heart. So one day, when his heart was in a state of turmoil he cried out:

“God, if perchance you exist, it is Your duty to reveal yourself to me.”

Shorthly after he prayed that prayer, he met a German carpenter in his village who gave him a bible. The carpenter and his wife had been praying earnestly that God would bring a Jew to his village, because the carpenter wanted to bring a Jew to Christ, because Jesus was a Jew. So the carpenter gave him a Bible to read. Wurmbrand said, when he opened that Bible he could not stop weeping. He had read the Bible before but it had meant nothing to him. This time when he opened the Bible he could barely read it because of the copious amount of tears that filled his eyes. Sometime later he found out the carpenter and his wife had been praying earnestly for him. Wurnbrand said that every word that he read were like flames of love burning in his heart. He realized for the first ime in his life that there was a God of love who loved him, even though he had beeen living a bad life and had nurtured a hated towards the concept of a ‘loving’ God.

The Power of Intercessory Prayer

But now for the first time he knew that Jesus had suffered at the cross of Calvary for his sins and he was loved and accepted of God. Richard and his wife became believers in Jesus the Messiah. All the hatred that he had formerly held toward God was washed away under the blood of Christ and Richard and his wife Sabrina were born of the Spirit. That is the power of intercessory prayer!

Richard prepared himself for the ministry. He was ordained as an Anglican minister in 1938 at the start of world war 2. Both Richard and his wife were arrested several times. They were beaten and hauled before a Nazi court. They suffered under the Nazi regime throughout world war 2. But Richard said, it was only a taste of what was to come.

Russian Troups Enter Romania

Towards the end of world war 2, Richard Wurmbrand became a Lutheran and he pastored a Lutheran church in Romania. But, the same year, 1 million Russian troups entered and occupied the entire territory of Romania.

Within a very short space of time the Communists took over Romania. The reign of terror began. Out of fear 4,000 priests, pastors & ministers became Communists overnight. They confessed their allegience and loyalty to the new Communist Government because they all feared for their survival.

Romania’s Resistance

Harsh persecutions of any enemies of the Communist government started with the Soviet occupation in 1945. The Soviet army behaved as an occupation force (although theoretically it was an ally against Nazi Germany), and could arrest virtually anyone at will. Shortly after Soviet occupation, ethnic Germans (who were Romanian citizens and had been living as a community in Romania for 800 years) were deported to the Donbas coal mines. Despite the King’s protest, who pointed out that this was against international law, an estimated 70,000 men and women were forced to leave their homes, starting in January 1945, before the war had even ended. They were loaded in cattle cars and put to work in the Soviet mines for up to ten years as “reparations”, where about one in five died from disease, accidents and malnutrition.

Once the Communist government became more entrenched, the number of arrests increased. All strata of society were involved, but particularly targeted were the pre-war elites, such as intellectuals, clerics, teachers, former politicians (even if they had left-leaning views) and anybody who could potentially form the nucleus of anti-Communist resistance. The existing prisons were filled with political prisoners, and a new system of forced labor camps and prisons was created, modeled after the Soviet Gulag. Some of the most notorious prisons included Sighet, Gherla, Piteşti and Aiud, and forced labor camps were set up at lead mines and in the Danube Delta.

Underground Church

Richard and his wife knew that Christianity and Communism were totally opposed to each other. They knew that a true follower of Christ cannot compromise. So they created an “Underground Church” movement to preach the pure gospel of Christ and to reach out to the unsaved people of Romania and secondly to reach out secretly to the Russian soldiers. They secretly printed thousands of Bibles and Christian literature and distributed it to the Russian soldiers. Many of the Russian soldiers were convicted and they gave their life to Christ.

So the underground church grew. But, in 1948 the Secret Police arrested Wurmbrand and he was placed in solitary confinement for 3 years. He was then transferred to a group cell for the next five years. Whilst in prison he continued to win the other prisoners to Christ. After 8 years in prison he was released and he immediately resumed his work with the undergound church. A few years later, 1959, he was arrested again and was sentenced to 25 years in prison. However, after spending 5 years in prison an organisation called the Christian Alliance negotiated with the Communist Government and they managed to secure his release for a fee of $10,000. They quickly got Richard Wurmbrand out of Romania and took him to England, then to the USA.

In 1966, Richard was called to Washington DC to give his testimony before the United States Senate. He took off his shirt to show the Senate the scars and the wounds that he received whilst he served time in prison under the Communist Government in Romania.

The newspapers throughout the USA, Europe and Asia carried his story all across the world. Christian leaders called him the “Voice of the Underground Church.”

In 1967, with a $100 old typewriter and 500 names and addresses, Richard Wurmbrand published the first issue of THE VOICE OF THE MARTYRS newsletter. This newsletter was dedicated to communicating the testimonies and trails facing our brothers and sisters in restricted nations worldwide. Richard wrote:

“The message I bring from the Underground Church is:

“Don’t abandon us!”

“Don’t forget us!”

“Don’t write us off!”

“Give us the tools we need! We will pay the price for using them!”

“This is the message I have been charged to deliver to the free church.”

Richard Wurmbrand and his wife travelled throughout the world to establish a network of over 30 offices. Their primary aim was to call Christians to shoulder their responsibility and to demonstrate the real substance of their faith by supporting their brothers and sisters in Christ who are being persecuted in heathen lands.

The VOICE OF THE MARTYRS newsletter continues to inform, and lead to action, Christians throughout the free world of the plight of those who suffer for their faith in Jesus Christ. Throughout their network of offices around the world, the newsletter is published in over 30 different languages. To this cause, VOICE OF THE MARTYRS presses on, serving in nearly 40 countries around the world where our brothers and sisters are systematically persecuted.

The writer of the Book of Hebrews brings a convicting word to the Christian church:

” Remember them that are in bonds, as bound with them; and them that suffer adversity, as being yourselves also in the body.”

(Hebrews 13:3)

We have a responsibility to those who suffer for their faith in Christ.

Today, there is an estimated 200 million Christians in heathen nations who are suffering persecution for their faith in Christ.

The Perfect City

He has prepared for them a city. (Hebrews 11:16) No pollution, no graffiti, no trash, no peeling paint or rotting garages, no dead grass or broken bottles, no harsh street talk, no in-your-face confrontations, no domestic strife or violence, no dangers in the night, no arson or lying or stealing or killing, no vandalism, and no ugliness. The city of God will be perfect, because God will be in it. He will walk in it and talk in it and manifest himself in every part of it. All that is good and beautiful and holy and peaceful and true and happy will be there, because God will be there. Perfect justice will be there and recompense a thousandfold for every pain suffered in obedience to Christ in this world. And it will never deteriorate. In fact, it will shine brighter and brighter as eternity stretches out into unending ages of increasing joy. When you desire this city above everything else on the earth, then you honor God, who, according to Hebrews 11:10, is the designer and builder of the city. And when God is honored, he is pleased and not ashamed to be called your God. Devotional by John Piper