Others like anagkazo: compelling power Features >>

6 Steps To Multiplication

Jeshua Hamashiah

-160.webp)

Friend Of Sinners (Why Jesus Cares More About Relationship Than Perfection)

True Revivals And The Men God Uses

The Most Important Decision You Will Ever Make

Why Jesus Appears To People Today

Many Are Called

Time Is Running Out

-160.webp)

Evidence For The Resurrection (What It Means For Your Relationship With God)

The Gospel Commission

About the Book

"Anagkazo: Compelling Power" by Dag Heward is a book that explores the concept of anagkazo, which means compelling power in Greek. The author delves into the idea of tapping into one's inner strength and experiencing the transformative power of faith and determination. The book emphasizes the importance of overcoming challenges and obstacles through faith and unwavering belief in oneself.

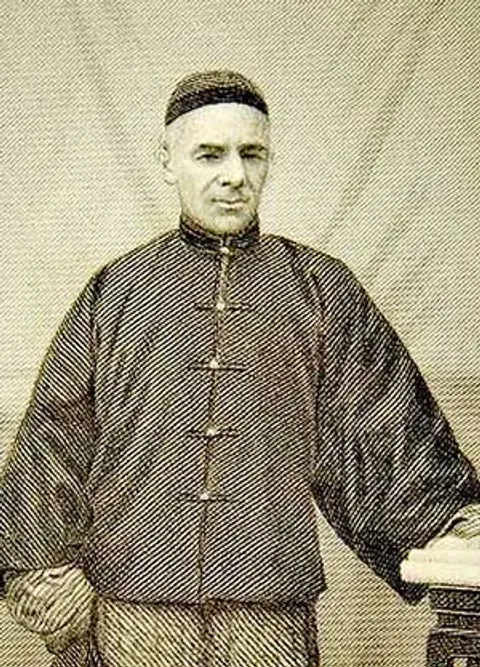

William Chalmers Burns

William Chalmers Burns was born in the Manse of Dun, in Angus, on April Ist, 1815. He was the third son of the Parish Church minister there. After leaving school, he went to Edinburgh to be apprenticed with an uncle to the legal profession. His eldest sister, a gay young lady, was converted to God, and became a bright witness for the Lord Jesus in 1831, and it was by means of her decided testimony that William was first awakened to a sense of his need of salvation, and led to put his trust in the Son of God, as his Redeemer and Saviour.

It was shortly after his conversion that he walked into the manse of Kilsyth, where the family then resided, having walked on foot the thirty-six miles from Edinburgh, to tell his mother and his sisters the glad news of his conversion, and to say that his desire now was to relinquish his study of law, and devote himself entirely to the preaching of the Gospel of God’s grace to his fellowmen.

And this he did heartily and with all his might, first in the neglected Parts of Scotland, and latterly among many heathen millions of the great Chinese Empire, then scarcely touched by the feet of God’s messengers of peace.

Mr. Burns’s name came into prominence in connection with a wonderful work of grace in Dundee, while he was preaching for Robert Murray M’Cheyne, then on a visit to Palestine, for the evangelization of the Jews. During Mr. Burns’s preaching in Dundee, a remarkable awakening took place; thousands were aroused to their condition in the sight of God, truly converted, and set on the heavenward way.

Remarkable scenes were witnessed in the old church of St. Peter’s, near to which M’Cheyne’s body now lies, awaiting the first resurrection. It was on the evening of a Lord’s Day in Kilsyth, after preaching to a crowded congregation, that Mr. Burns felt constrained to intimate to the people that he would preach to the people in the open air, before returning to Dundee the following day.

Deeply burdened with the souls of the people, he went into the village and invited the people, who thronged into the old church, until every seat and passage was filled. And the Lord helped His servant to preach straight to the people with great power, with the result that the whole congregation became melted under the message, many weeping aloud and crying to God for mercy. A glorious work of conversion followed.

Meetings for prayer and preaching of the Gospel continued in the churchyard, the market-place and elsewhere for weeks, while Mr. Burns returned to Dundee to resume his ministry. The work progressed in Dundee with increased interest, until the return of Mr. M’Cheyne, who greatly rejoiced in all that the Lord had done during his absence, through the ministry of His servant.

There was no jealousy, but the deepest gratitude, and these two true ministers of Christ rejoiced together over the Lord’s doings, which were indeed marvellous in their eyes.

From that time onward, until the Lord’s call came to go to China, Mr. Burns gave himself almost wholly to itinerant Gospel preaching, through Perthshire, up as far north as Aberdeen, preaching in barns, on market-places, and wherever the people could be gathered together to hear the Word. His message was plain, and to the point; thousands were awakened and many saved. But the adversary opposed. Time and again Mr. Burns was stoned, and bore the marks of these brands of the enemy for many days.

Believing it to be the call of the Lord, he went forth to China as the first missionary of the Presbyterian Church of England, in June, 1847. When questioned by those interested in his out-going, how long it would take him to prepare for the voyage, he replied with all simplicity, “I will be ready to go to-morrow.”

On a brief visit to his home, to take farewell of his sister, he silently wrung her hand, took a last glance around their old home, and with a small bag in his hand and his mother’s plaid across his arm, went forth, in the Name of the Lord with the Gospel to China’s benighted people, of whom it was said “a million a month” were dying without having once heard the Gospel.

For years this solitary witness toiled alone, at times with a few helpers, in the great heathen land, amid overwhelming hindrances, but his faith in God never faltered. On and on he went, sowing the seed which others would reap, until he reached the borders of the great kingdom of Manchuria, where, in a small, comfortless room in Nieu-chang, wearied and worn in labours abundant, he fell asleep on April 4th, 1868, his last audible words being, “For Thine is the Kingdom and the Power and the Glory.”

It is of this great land that the story of grace related in the following pages is told, and those who saw and shared in its joyful results, say that it was no doubt part of the result of William Burns’s sowing, in his earlier years in China.

William Chalmers Burns was born in the Manse of Dun, in Angus, on April Ist, 1815. He was the third son of the Parish Church minister there. After leaving school, he went to Edinburgh to be apprenticed with an uncle to the legal profession. His eldest sister, a gay young lady, was converted to God, and became a bright witness for the Lord Jesus in 1831, and it was by means of her decided testimony that William was first awakened to a sense of his need of salvation, and led to put his trust in the Son of God, as his Redeemer and Saviour.

It was shortly after his conversion that he walked into the manse of Kilsyth, where the family then resided, having walked on foot the thirty-six miles from Edinburgh, to tell his mother and his sisters the glad news of his conversion, and to say that his desire now was to relinquish his study of law, and devote himself entirely to the preaching of the Gospel of God’s grace to his fellowmen.

And this he did heartily and with all his might, first in the neglected Parts of Scotland, and latterly among many heathen millions of the great Chinese Empire, then scarcely touched by the feet of God’s messengers of peace.

Mr. Burns’s name came into prominence in connection with a wonderful work of grace in Dundee, while he was preaching for Robert Murray M’Cheyne, then on a visit to Palestine, for the evangelization of the Jews. During Mr. Burns’s preaching in Dundee, a remarkable awakening took place; thousands were aroused to their condition in the sight of God, truly converted, and set on the heavenward way.

Remarkable scenes were witnessed in the old church of St. Peter’s, near to which M’Cheyne’s body now lies, awaiting the first resurrection. It was on the evening of a Lord’s Day in Kilsyth, after preaching to a crowded congregation, that Mr. Burns felt constrained to intimate to the people that he would preach to the people in the open air, before returning to Dundee the following day.

Deeply burdened with the souls of the people, he went into the village and invited the people, who thronged into the old church, until every seat and passage was filled. And the Lord helped His servant to preach straight to the people with great power, with the result that the whole congregation became melted under the message, many weeping aloud and crying to God for mercy. A glorious work of conversion followed.

Meetings for prayer and preaching of the Gospel continued in the churchyard, the market-place and elsewhere for weeks, while Mr. Burns returned to Dundee to resume his ministry. The work progressed in Dundee with increased interest, until the return of Mr. M’Cheyne, who greatly rejoiced in all that the Lord had done during his absence, through the ministry of His servant.

There was no jealousy, but the deepest gratitude, and these two true ministers of Christ rejoiced together over the Lord’s doings, which were indeed marvellous in their eyes.

From that time onward, until the Lord’s call came to go to China, Mr. Burns gave himself almost wholly to itinerant Gospel preaching, through Perthshire, up as far north as Aberdeen, preaching in barns, on market-places, and wherever the people could be gathered together to hear the Word. His message was plain, and to the point; thousands were awakened and many saved. But the adversary opposed. Time and again Mr. Burns was stoned, and bore the marks of these brands of the enemy for many days.

Believing it to be the call of the Lord, he went forth to China as the first missionary of the Presbyterian Church of England, in June, 1847. When questioned by those interested in his out-going, how long it would take him to prepare for the voyage, he replied with all simplicity, “I will be ready to go to-morrow.”

On a brief visit to his home, to take farewell of his sister, he silently wrung her hand, took a last glance around their old home, and with a small bag in his hand and his mother’s plaid across his arm, went forth, in the Name of the Lord with the Gospel to China’s benighted people, of whom it was said “a million a month” were dying without having once heard the Gospel.

For years this solitary witness toiled alone, at times with a few helpers, in the great heathen land, amid overwhelming hindrances, but his faith in God never faltered. On and on he went, sowing the seed which others would reap, until he reached the borders of the great kingdom of Manchuria, where, in a small, comfortless room in Nieu-chang, wearied and worn in labours abundant, he fell asleep on April 4th, 1868, his last audible words being, “For Thine is the Kingdom and the Power and the Glory.”

It is of this great land that the story of grace related in the following pages is told, and those who saw and shared in its joyful results, say that it was no doubt part of the result of William Burns’s sowing, in his earlier years in China.

five ways to build stronger relationships

“That used to be nice.” That was the first response when I recently asked a group of men what comes to mind when they think about friendship. Once they entered their upper twenties and thirties, many of them no longer had close friendships. We mostly laughed when joking about Jesus’s “miracle” of having twelve close friends in his thirties. Many factors combine to make friendship difficult for men. Personally, time for friends seems unrealistic in light of work or family responsibilities. Culturally, we don’t have a shared understanding of what friendships among men should look like. We also find ourselves connecting more digitally than deeply. We’ve lost a vision for strong, warm, face-to-face and side-by-side male friendship. But God made us for more. He made us in his own image, the image of a triune God who exists in communal love. Therefore, friendship is not a luxury; it’s a relational necessity. We glorify God by enjoying him and reflecting his relational love with one another. If you are a man who has struggled to go deeper with other men, here are five concrete steps to cultivate deeper friendships. 1. Establish rhythms for your relationships. Without rhythms in our lives, the important priorities don’t get done. If we value communing with God through his word and prayer, we form a habit. If we want to exercise consistently, we create a pattern. Here’s a proposal for cultivating friendship: Build it into your schedule. Establish a regular rhythm for coffee together. Devote a meal each week — say, Monday breakfasts or Wednesday dinners — to share with others. Plan to meet up to take walks together. Reserve an extended weekend each year to get away and enjoy God’s creation together. 2. Drop each conversation one notch deeper. Conversations about sports and daily activities are worthwhile. But if that’s all we talk about, it’s like snorkeling on the surface while missing the deeper wonders of the ocean. But how do we take our conversations deeper? First, ask thoughtful questions. When you’re driving to meet your friend, think about what you want to learn about him. Think about the main aspects of his life right now — his relationship with the Lord, his family, his work — and ask him about how things are going. When he shares about a challenge, ask how his internal life (his heart, his disposition toward God) is doing in the midst of this. From there, stay curious and ask more questions. Second, talk about what you’re each reading. Ask how God’s word has convicted or encouraged him recently. Ask what book he’s recently read that helped him know God or live more faithfully as a disciple. Consider reading through Scripture or a Scripture-saturated book together and meeting to talk about it. 3. Overcome our cultural aversion to expressing affection. “Love one another with brotherly affection” (Romans 12:10). We don’t usually put those last two words next to one another — brotherly feels masculine; affection feels feminine. But there they are together, inviting us to cultivate genuine, non-weird, affectionate brotherhood. We see this affectionate bond with Jonathan and David: “The soul of Jonathan was knit to the soul of David, and Jonathan loved him as his own soul” (1 Samuel 18:1). We see it with Paul and the Ephesian elders: “And there was much weeping on the part of all; they embraced Paul and kissed him” (Acts 20:37). Expressing affection feels uncomfortable to men today because our culture has slowly shifted its understanding of masculinity. Rather than combining strength and tenderness, we view manhood as muscular and aggressive. Our culture has also sexualized love, interpreting affection between men as something other than friendship. But we can build a better way. 4. Oxygenate your friendships with affirmation. What happens without oxygen? We become sluggish and lethargic. This is what relationships feel like without affirmation. This may be why some of your relationships feel withered, thin, or tired. Affirmation is relational oxygen. One of the most powerful tools for cultivating true friendship is Romans 12:10: “Outdo one another in showing honor.” Men find it hard to give and receive honor and affirmation. It feels uncomfortable at first to tell someone why you thank God for him or why you respect him. But only at first. I’ve seen many men work through their initial hesitations and start cultivating a culture of sincere encouragement around them. And I’ve seen the other men flourish because of it. 5. Invite friends into what you’re already doing. Our schedules are full and we rush from one thing to the next. We don’t see how we can find time for friends. But what if you don’t need to open up your schedule? What if you can include friends into the activities you already do? Here are a few suggestions I’ve seen work: When you plan to watch a sports game or weekly show, find out who else would want to watch it and invite them to join you. If you exercise a few times each week, do it with a friend. Invite friends or family members to join you for dinner or dessert. If you have young kids, let your guests participate in the bedtime routine and then stay around afterward. If you have young kids, invite someone to join your family at the park. Put a few friends on speed dial and call them on your daily commute home. If you have a home project to complete, invite someone to help you and offer to help him with his. Hope and Help for Forging Friendship Jesus is our greatest model of male friendship. He initiated relationships and he invited men to be with him (Mark 3:14). He continually asked thought-provoking questions. He loved his disciples with brotherly affection (John 13:1). He calls us his friends (John 15:13–15). He also gives us the great privilege of reflecting and enjoying this kind of true friendship to other men. Maybe as you consider taking these steps, you look ahead with both hope and hesitancy. Maybe you think back to when you experienced deeper community and think you won’t find that again. Or maybe you still feel pain from failed attempts at connecting with others. You wonder if forging friendship is harder, even impossible, for you. Before you give up, remember two truths: First, Jesus isn’t just the model for true friendship; he is himself our truest friend. He initiates friendship with us, and we receive it on terms of grace. Now “no one need ever say I have no ‘friend’ to turn to, so long as Christ is in heaven” (J.C. Ryle, Expository Thoughts , 3:114). And second, he delights for us to ask for true community in his name. God alone is able to create, renew, and strengthen the deepest human relationships. So, pray. Ask God to make your efforts at friendship fruitful. Then trust him, stay patient, and keep taking steps toward others in the strength he provides.