About the Book

"And Jesus Healed Them All" by Gloria Copeland explores the healing power of Jesus as described in the Bible. The book delves into the stories of various individuals who were healed by Jesus, emphasizing the importance of faith and belief in receiving healing miracles. Copeland also offers practical guidance on how readers can experience healing in their own lives through prayer and faith in God.

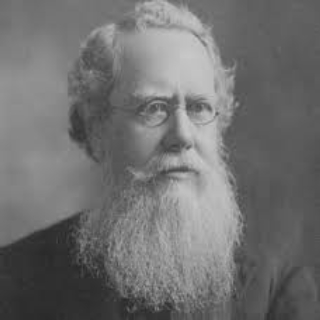

Hudson Taylor

The Story of John Bunyan's ‘Pilgrim's Progress’

On the morning of November 12, 1660, a young pastor entered a small meeting house in Lower Samsell, England, preparing to be arrested. He hadn’t noticed the men keeping guard outside the house, but he didn’t need to. A friend had warned him that they were coming. He came anyway. He had agreed to preach. The constable broke in upon the meeting and began searching the faces until he found the one he came for: a tall man, wearing a reddish mustache and plain clothes, paused in the act of prayer. John Bunyan by name. “Had I been minded to play the coward, I could have escaped,” Bunyan later remembered. But he had no mind for that now. He spoke what closing exhortation he could as the constable forced him from the house, a man with no weapon but his Bible. Two months and several court proceedings later, Bunyan was taken from his church, his family, and his job to serve “one of the longest jail terms . . . by a dissenter in England” (On Reading Well, 182). For twelve years, he would sleep on a straw mat in a cold cell. For twelve years, he would wake up away from his wife and four young children. For twelve years, he would wait for release or, if not, exile or execution. And in those twelve years, he began a book about a pilgrim named Christian — a book that would become, for over two centuries, the best-selling book written in the English language. Tinker Turned Preacher John Bunyan (1628–1688) was not the most likely Englishman to write The Pilgrim’s Progress, a book that would be translated into two hundred languages, that would capture the imaginations of children and scholars alike, and that would rank, in influence and popularity, just behind the King James Bible in the English-speaking world. “Bunyan is the first major English writer who was neither London-based nor university-educated,” writes Christopher Hill. Rather, “the army had been his school, and prison his university” (The Life, Books, and Influence of John Bunyan, 168). “‘Pilgrim’s Progress’ bears the marks of John Bunyan’s confinement. Without the prison, we may not have the pilgrim.” As Paul said of the Corinthians, so we might say of Bunyan: he had few advantages “according to worldly standards” (1 Corinthians 1:26). In his spiritual autobiography, Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners, he confesses that his father’s house was “of that rank that is meanest and most despised of all the families in the land” (7). Thomas Bunyan was a tinker, a traveling mender of pots, pans, and other metal utensils. Thomas sent his son to school only briefly, where John learned to read and write. Later, after a stint in the army, he followed his father into the tinker trade. Meanwhile, Bunyan recalls, “I had but few equals, especially considering my years, which were tender, being few, both for cursing, swearing, lying, and blaspheming the name of God” (Grace Abounding, 8). Sometime in Bunyan’s early twenties, however, God laid his hand on the blasphemous tinker and began to press. For the first time, Bunyan felt the load of sin and guilt on his back, and despair nearly sunk him. He agonized over his soul for years before he was finally able to say, “Great sins do draw out great grace; and where guilt is most terrible and fierce, there the mercy of God in Christ, when showed to the soul, appears most high and mighty” (Grace Abounding, 97). Bunyan soon carried this travail and triumph of grace into the pulpit of a Bedford church, where he heralded Christ so powerfully that congregations throughout Bedfordshire County began asking for the tinker turned preacher — including a small gathering of believers in Lower Samsell. Trying Days for Dissenters Not everyone in England responded warmly to Bunyan’s preaching, however. “He lived in more trying days than those in which our lot is fallen,” wrote John Newton a century later (“Preface to The Pilgrim’s Progress,” xxxix). Yes, these were trying days — at least for dissenting pastors like Bunyan, who refused to join the Church of England. Throughout the seventeenth century, dissenters were sometimes honored, sometimes ignored, and sometimes arrested by England’s authorities. Bunyan’s lot fell into the last of these. Some dissenters did not exactly help the cause. A Puritan sect called the Fifth Monarchy Men, for example, took to arms in 1657 and 1661 in order to claim England’s crown for the (supposedly) soon-to-return Christ. Often, then, “the authorities did not seek to suppress Dissenters as heretics but as disturbers of law and order,” David Calhoun explains (Life, Books, and Influence, 28). Bunyan was no radical — simply a tinker who preached without an official license. Still, the Bedfordshire authorities thought it safer to silence him. Once arrested, Bunyan was given an ultimatum: If he would agree to cease preaching and remain quiet in his calling as a tinker, he could return to his family at once. If he refused, imprisonment and potential exile awaited him. At one point in the proceedings (which lasted several weeks), Bunyan responded, If any man can lay anything to my charge, either in doctrine or practice, in this particular, that can be proved error or heresy, I am willing to disown it, even in the very market place; but if it be truth, then to stand to it to the last drop of my blood. (Grace Abounding, 153) Bunyan was then 32 years old. He would not be a free man again until age 44. Bedford Jail Despite Bunyan’s boldness before the magistrates, his decision was not an easy one. Most trying of all was his separation from Elizabeth, his wife, and their four young children, one of whom was blind. Years into his jail time, he would write, “The parting with my wife and poor children has oft been to me in this place as the pulling the flesh from my bones” (Grace Abounding, 122). He would make shoelaces over the next twelve years to help support them. But Bunyan would not ultimately regret his decision. Though parted from the comfort of his family, he was not parted from the comfort of his Master. “Jesus Christ . . . was never more real and apparent than now,” the imprisoned Bunyan wrote. “Here I have seen him and felt him indeed” (Grace Abounding, 119). “The best designs of the devil can only serve the progress of God’s pilgrims.” With comfort in his soul, then, Bunyan gave himself to whatever ministry he could. He counseled visitors. He and other inmates preached to each other on Sundays. But most of all, Bunyan wrote. In jail, with his Bible and Foxe’s Book of Martyrs close at hand, he penned Grace Abounding. There also, as he was working on another book, an image of a path and a pilgrim flashed upon his mind. “And thus it was,” Bunyan wrote in a poem, I, writing of the way And race of saints, in this our gospel day, Fell suddenly into an allegory, About their journey, and the way to glory. (Pilgrim’s Progress, 3) Thus began the book that would soon be read, not only in Bunyan’s Bedford, but in Sheffield, Birmingham, Manchester, London — and eventually far beyond. The Bedford magistrates sought to silence Bunyan in jail. In jail, Bunyan sounded a trumpet that reached the ears of all the West, and even the world. Calvinism in Delightful Colors The genius of Bunyan’s book, along with its immediate popularity, owes much to the writer’s sudden fall “into an allegory.” As an allegory, Pilgrim’s Progress operates on two levels. On one level, the book is a storehouse of Puritan theology — “the Westminster Confession of Faith with people in it,” as someone once said. On another level, however, it is an enthralling adventure story — a journey of life and death from the City of Destruction to the Celestial City. The poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge would later write, “I could not have believed beforehand that Calvinism could be painted in such exquisitely delightful colors” (Life, Books, and Influence, 166). Those who read Pilgrim’s Progress find theology coming to them in dungeons and caves, in sword fights and fairs, in honest friends and two-faced flatterers. Bunyan does not merely tell us we must renounce all for Christ’s sake; he shows us Christian fleeing his neighbors and family, fingers in his ears, crying, “Life! life! eternal life!” (Pilgrim’s Progress, 14). Bunyan does not simply instruct us about our spiritual conflict; he makes us stand in the Valley of Humiliation with a “foul fiend . . . hideous to behold” striding toward us (66). Bunyan does not just warn us of the subtlety of temptation; he gives us sore feet on a rocky path, and then reveals a smooth road “on the other side of the fence” (129) — more comfortable on the feet, but the straightest way to a giant named Despair. The cast of characters in Pilgrim’s Progress reminds us that the path to the Celestial City is narrow — so narrow that only a few find it, while scores fall by the wayside. Here we meet Timorous, who flees backward at the sight of lions; Mr. Hold-the-world, who falls into Demas’s cave; Talkative, whose religion lives only in his tongue; Ignorance, who seeks entrance to the city by his own merits; and a host of others who, for one reason or another, do not endure to the end. “In jail, John Bunyan sounded a trumpet that reached the ears of all the West, and even the world.” And herein lies the drama of the story. Bunyan, a staunch believer in the doctrine of the saints’ perseverance, nevertheless refused to take that perseverance for granted. As long as we are on the path, we are “not yet out of the gun-shot of the devil” (101). Between here and our home, many enemies lie along the way. Nevertheless, let every pilgrim take courage: “you have all power in heaven and earth on your side” (101). If grace has brought us to the path, grace will guard our every step. ‘All We Do Is Succeed’ Within ten years of its publishing date in 1678, Pilgrim’s Progress had gone through eleven editions and made the Bedford tinker a national phenomenon. According to Calhoun, “Some three thousand people came to hear him one Sunday in London, and twelve hundred turned up for a weekday sermon during the winter” (Life, Books, and Influence, 38). If the Bedford magistrates had allowed Bunyan to continue preaching, we would still remember him today as the author of several dozen books and as one of the many Puritan luminaries. But in all likelihood, he would not be read today in some two hundred languages besides his own. For Pilgrim’s Progress is a work of prison literature — and it bears the marks of Bunyan’s confinement. Without the prison, we would likely not have the pilgrim. The story of Bunyan and his book, then, is yet one more illustration that God’s ways are high above our own (Isaiah 55:8–9), and that the best designs of the devil can only serve the progress of God’s pilgrims (Genesis 50:20). John Piper, reflecting on Bunyan’s imprisonment, says, “All we do is succeed — either painfully or pleasantly” (“The Chief Design of My Life”). Yes, if we have lost our burden at the cross, and now find ourselves on the pilgrims’ path, all we do is succeed. We succeed whether we feast with the saints in Palace Beautiful or wrestle Apollyon in the Valley of Humiliation. We succeed whether we fellowship with shepherds in the Delectable Mountains or lie bleeding in Vanity Fair. We succeed even when we walk straight into the last river, our feet reaching for the bottom as the water rises above our heads. For at the end of this path is a prince who “is such a lover of poor pilgrims, that the like is not to be found from the east to the west” (Pilgrim’s Progress, 61). Among the company of that prince is one John Bunyan, a pilgrim who has now joined the cloud of witnesses (Hebrews 12:1). “Though he died, he still speaks” (Hebrews 11:4) — and urges the rest of us onward. Article by Scott Hubbard