Others like road to armageddon Features >>

Death And The Life After

Dancing With Angels

I Went To Hell

The Rapture: What The Bible Says

.epub-160.webp)

An Exorcist Tells His Story

Beyond The Ancient Door

Rapture, Revelation, And The End Times: Exploring The Left Behind Series

A Citizen Of Two Worlds

-160.webp)

Heaven Is For Real: A Little Boy's Astounding Story Of His Trip To Heaven And Back

Miracles From Heaven

About the Book

"Road to Armageddon" by Grant R. Jeffrey explores the biblical prophecies concerning the end times and the events leading up to the battle of Armageddon. The author delves into topics such as the rise of the Antichrist, the rebuilding of the temple in Jerusalem, and the role of nations in the final battle. Through detailed analysis, Jeffrey discusses how current world events align with biblical predictions, offering insight into what may unfold in the future.

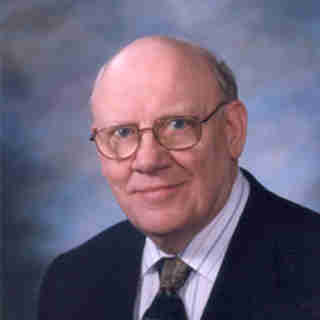

Warren Wiersbe

Dr. Warren Wiersbe once described Heaven as “not only a destination, but also a motivation. When you and I are truly motivated by the promise of eternity with God in heaven, it makes a difference in our lives.”

For Wiersbe, the promise of eternity became the motivation for his long ministry as a pastor, author, and radio speaker. Beloved for his biblical insight and practical teaching, he was called “one of the greatest Bible expositors of our generation” by the late Billy Graham.

Warren W. Wiersbe died on May 2, 2019, in Lincoln, Nebraska, just a few weeks shy of his 90th birthday.

“He was a longtime, cherished friend of Moody Bible Institute, a faithful servant of the Word, and a pastor to younger pastors like me,” said Dr. Mark Jobe, president of Moody Bible Institute. “We are lifting up pastor Wiersbe’s family in prayer at this time and rejoicing in the blessed hope that believers share together.”

Wiersbe grew up in East Chicago, Indiana, a town known for its steel mills and hard-working blue-collar families. In his autobiography, he connected some of his earliest childhood memories to Moody Bible Institute; his home church pastor was a 1937 graduate, Dr. William H. Taylor. After volunteering to usher at a 1945 Youth for Christ rally, Wiersbe found himself listening with rapt attention to Billy Graham’s sermon, and responded with a personal prayer of dedication.

In a precocious turn of events, the young Wiersbe was already a published author, having written a book of card tricks for the L. L. Ireland Magic Co. of Chicago. He quickly learned to liven up Sunday school lessons with magic tricks as object lessons (“not the cards!” he would say). After his high school graduation in 1947 (he was valedictorian), he spent a year at Indiana University before transferring to Northern Baptist Seminary in Chicago, where he earned a bachelor of theology degree. His future wife, Betty, worked in the school library, and Wiersbe was a frequent visitor.

While in seminary he became pastor of Central Baptist Church in East Chicago, serving until 1957. During those years he became a popular YFC speaker, which led to a full-time position with Youth for Christ International in Wheaton. He published his first article for Moody Monthly magazine in 1956, about Bible study methods, and seemed to outline his ongoing writing philosophy. “This is more of a personal testimony,” he said, “because I want to share these blessings with you, rather than write some scholarly essay, which I am sure I could not do anyway.”

At a 1957 YFC convention in Winona Lake, Indiana, Wiersbe preached a sermon that was broadcast live over WMBI, his first connection to Moody Radio. “I wish every preacher could have at least six months’ experience as a radio preacher,” he said later (because they would preach shorter).

While working with Youth for Christ, Wiersbe got a call from Pete Gunther at Moody Publishers, asking about possible book projects. First came Byways of Blessing (1961), an adult devotional; then two more books in 1962, A Guidebook for Teens and Teens Triumphant. He would eventually publish 14 titles with Moody, including William Culbertson: A Man of God (1974), Live Like a King (1976), The Annotated Pilgrim’s Progress (1980), and Ministering to the Mourning (2006), written with his son, David Wiersbe.

In 1961, D. B. Eastep invited Wiersbe to join the staff of Calvary Baptist Church in Covington, Kentucky. forming a succession plan that was hastened by Eastep’s sudden death in 1962. Warren and Betty Wiersbe remained at the church for 10 years, until they were surprised by a phone call from The Moody Church. The pastor, Dr. George Sweeting, had just resigned to become president of Moody Bible Institute. Would Wiersbe fill the pulpit, and pray about becoming a candidate?

He was already well known to the Chicago church—and to the MBI community. He continued to write for Moody Monthly and had just started a new column, “Insights for the Pastor.” The monthly feature continued to run during the years Wiersbe served at The Moody Church. Wiersbe would become one of the magazine’s most prolific writers—200 articles during a 40-year span. Meanwhile he also started work on the BE series of exegetical commentaries, books that soon found a place on the shelf of every evangelical pastor.

His ministry to pastors continued as he spoke at Moody Founder’s Week, Pastors’ Conference, and numerous campus events. He also inherited George Sweeting’s role as host of the popular Songs in the Night radio broadcast, produced by Moody Radio’s Bob Neff and distributed on Moody’s growing network of radio stations.

Later in life he would move to Lincoln, Nebraska, where he served as host of the Back to the Bible radio broadcast. He also taught courses on preaching at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School and Grand Rapids Baptist Seminary. He kept writing, eventually publishing more than 150 books and losing track of how many (“I can’t remember them all, and I didn’t save copies of everything,” he said.)

Throughout his ministry, Warren Wiersbe described himself as a bridge builder, a reference to his homiletical method of moving “from the world of the Bible to the world of today so that we could get to the other side of glory in Jesus.” As explained by his grandson, Dan Jacobson, “His preferred tools were words, his blueprints were the Scriptures, and his workspace was a self-assembled library.”

Several of Wiersbe’s extended family are Moody alums, including a son, David Wiersbe ’76; grandson Dan Jacobsen ’09 and his wife, Kristin (Shirk) Jacobsen ’09; and great-nephew Ryan Smith, a current student.

During his long ministry and writing career, Warren Wiersbe covered pretty much every topic, including the inevitability of death. These words from Ministering to the Mourning offer a fitting tribute to his own ministry:

We who are in Christ know that if He returns before our time comes to die, we shall be privileged to follow Him home. God’s people are always encouraged by that blessed hope. Yet we must still live each day soberly, realizing that we are mortal and that death may come to us at any time. We pray, “Teach us to number our days aright, that we may gain a heart of wisdom” (Psalm 90:12).

Dr. Warren Wiersbe once described Heaven as “not only a destination, but also a motivation. When you and I are truly motivated by the promise of eternity with God in heaven, it makes a difference in our lives.”

For Wiersbe, the promise of eternity became the motivation for his long ministry as a pastor, author, and radio speaker. Beloved for his biblical insight and practical teaching, he was called “one of the greatest Bible expositors of our generation” by the late Billy Graham.

Warren W. Wiersbe died on May 2, 2019, in Lincoln, Nebraska, just a few weeks shy of his 90th birthday.

“He was a longtime, cherished friend of Moody Bible Institute, a faithful servant of the Word, and a pastor to younger pastors like me,” said Dr. Mark Jobe, president of Moody Bible Institute. “We are lifting up pastor Wiersbe’s family in prayer at this time and rejoicing in the blessed hope that believers share together.”

Wiersbe grew up in East Chicago, Indiana, a town known for its steel mills and hard-working blue-collar families. In his autobiography, he connected some of his earliest childhood memories to Moody Bible Institute; his home church pastor was a 1937 graduate, Dr. William H. Taylor. After volunteering to usher at a 1945 Youth for Christ rally, Wiersbe found himself listening with rapt attention to Billy Graham’s sermon, and responded with a personal prayer of dedication.

In a precocious turn of events, the young Wiersbe was already a published author, having written a book of card tricks for the L. L. Ireland Magic Co. of Chicago. He quickly learned to liven up Sunday school lessons with magic tricks as object lessons (“not the cards!” he would say). After his high school graduation in 1947 (he was valedictorian), he spent a year at Indiana University before transferring to Northern Baptist Seminary in Chicago, where he earned a bachelor of theology degree. His future wife, Betty, worked in the school library, and Wiersbe was a frequent visitor.

While in seminary he became pastor of Central Baptist Church in East Chicago, serving until 1957. During those years he became a popular YFC speaker, which led to a full-time position with Youth for Christ International in Wheaton. He published his first article for Moody Monthly magazine in 1956, about Bible study methods, and seemed to outline his ongoing writing philosophy. “This is more of a personal testimony,” he said, “because I want to share these blessings with you, rather than write some scholarly essay, which I am sure I could not do anyway.”

At a 1957 YFC convention in Winona Lake, Indiana, Wiersbe preached a sermon that was broadcast live over WMBI, his first connection to Moody Radio. “I wish every preacher could have at least six months’ experience as a radio preacher,” he said later (because they would preach shorter).

While working with Youth for Christ, Wiersbe got a call from Pete Gunther at Moody Publishers, asking about possible book projects. First came Byways of Blessing (1961), an adult devotional; then two more books in 1962, A Guidebook for Teens and Teens Triumphant. He would eventually publish 14 titles with Moody, including William Culbertson: A Man of God (1974), Live Like a King (1976), The Annotated Pilgrim’s Progress (1980), and Ministering to the Mourning (2006), written with his son, David Wiersbe.

In 1961, D. B. Eastep invited Wiersbe to join the staff of Calvary Baptist Church in Covington, Kentucky. forming a succession plan that was hastened by Eastep’s sudden death in 1962. Warren and Betty Wiersbe remained at the church for 10 years, until they were surprised by a phone call from The Moody Church. The pastor, Dr. George Sweeting, had just resigned to become president of Moody Bible Institute. Would Wiersbe fill the pulpit, and pray about becoming a candidate?

He was already well known to the Chicago church—and to the MBI community. He continued to write for Moody Monthly and had just started a new column, “Insights for the Pastor.” The monthly feature continued to run during the years Wiersbe served at The Moody Church. Wiersbe would become one of the magazine’s most prolific writers—200 articles during a 40-year span. Meanwhile he also started work on the BE series of exegetical commentaries, books that soon found a place on the shelf of every evangelical pastor.

His ministry to pastors continued as he spoke at Moody Founder’s Week, Pastors’ Conference, and numerous campus events. He also inherited George Sweeting’s role as host of the popular Songs in the Night radio broadcast, produced by Moody Radio’s Bob Neff and distributed on Moody’s growing network of radio stations.

Later in life he would move to Lincoln, Nebraska, where he served as host of the Back to the Bible radio broadcast. He also taught courses on preaching at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School and Grand Rapids Baptist Seminary. He kept writing, eventually publishing more than 150 books and losing track of how many (“I can’t remember them all, and I didn’t save copies of everything,” he said.)

Throughout his ministry, Warren Wiersbe described himself as a bridge builder, a reference to his homiletical method of moving “from the world of the Bible to the world of today so that we could get to the other side of glory in Jesus.” As explained by his grandson, Dan Jacobson, “His preferred tools were words, his blueprints were the Scriptures, and his workspace was a self-assembled library.”

Several of Wiersbe’s extended family are Moody alums, including a son, David Wiersbe ’76; grandson Dan Jacobsen ’09 and his wife, Kristin (Shirk) Jacobsen ’09; and great-nephew Ryan Smith, a current student.

During his long ministry and writing career, Warren Wiersbe covered pretty much every topic, including the inevitability of death. These words from Ministering to the Mourning offer a fitting tribute to his own ministry:

We who are in Christ know that if He returns before our time comes to die, we shall be privileged to follow Him home. God’s people are always encouraged by that blessed hope. Yet we must still live each day soberly, realizing that we are mortal and that death may come to us at any time. We pray, “Teach us to number our days aright, that we may gain a heart of wisdom” (Psalm 90:12).

A Father’s Good Pleasure

A recent experience stirred in me a desire to share a word for fathers. I have fathers of younger children particularly in mind, those on the front end of their fathering days, when a man is seeking to establish godly habits so that, by his example, his children might see the shadow of their heavenly Father. This word, however, is also relevant to fathers of teens and young adults, like me, as well as for elderly fathers whose children are well into adulthood. I hope even those in situations where a father is absent will be able to draw out applications for themselves. But before I unpack this threefold word of biblical counsel, allow me to share my recent experience with you, since it both inspired and illustrates what I have to say. Because I Love You One Friday morning a few months back, I sent a text to my sixteen-year-old daughter, Moriah. Before sharing the text, let me share a bit of context. I began giving each of my five children a weekly allowance when they were around the age of seven. Then, at different points as they grew older, I sought to help them put age-appropriate budget structures in place to equip them to handle money well. When each approached age sixteen, I let them know that their allowance would end when they were old enough to be employed. A few days before I sent my text, Moriah began her first job, which meant it was her last allowance week. So, early that Friday morning, I transferred the funds into her account. I wasn’t at all prepared for the tears. Why was I crying? I tried to capture why in this (slightly edited) text I sent to her shortly after: I just transferred your allowance into your account. In the little memo window, I typed “Mo’s final allowance payment,” and suddenly a wave of emotion hit me, catching me by surprise. I’m standing here at my desk, alone in the office, my eyes full of tears, swallowing down sobs. Another chapter closed, another little step in letting you go. A decade of slipping you these small provisions each week to, yes, try and teach you how to handle money (not sure how well I’ve done in that department), but also, and far more so (when it comes to this father’s heart), out of the joy of just making you happy in some small way. At bottom, that’s what it’s been for me: a weekly joy of having this small way of saying, “I love you.” I’ll miss it. Because I love you. I still can’t read that without tearing up. I so enjoy every chance I get to give my children joy. As I stood there, trying to pull myself together, a Scripture text quickly came to mind: Which one of you, if his son asks him for bread, will give him a stone? Or if he asks for a fish, will give him a serpent? If you then, who are evil, know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will your Father who is in heaven give good things to those who ask him! (Matthew 7:9–11) And as I pondered this passage, I thought of some friends who are fathers of young children and jotted down three lessons I wanted to share with them. Pursue Your Pleasure for God’s Sake God means for you to taste the great pleasure it gives him to make his children happy through how much pleasure it gives you to make your children happy. “Fathers, become a student of what gives your children joy.” So, pursue your pleasure in making your children happy! Give them good things — things they value as good and really want. And really, authentically enjoy doing it. It has God’s endorsement, since he too takes great pleasure in giving good gifts to his children. What’s wonderful about this pleasurable experience is that, for a Christian father, it is multidimensional: we get the joy of blessing our children and the joy of tasting our heavenly Father’s joy in blessing us. This becomes an opportunity to exercise what C.S. Lewis called “transposition” (in his essay by that name in The Weight of Glory) — we see and savor the higher, richer pleasure of God in the natural pleasure of giving pleasure to our children. Pursue Your Children’s Pleasure God means for your children to taste how much pleasure it gives him to make his children happy through how much pleasure it gives you to make them happy. So, pursue your children’s pleasure in making your children happy! Become, through your joyful, affectionate generosity, an opportunity for your children to experience transposition too — to see and savor the higher, richer pleasure of God in the natural pleasure of their father giving good gifts to them. Become a student of what gives them joy. Watch for those few opportunities during their childhood to bless them with a lifetime memory (think Ralphie’s Red Ryder BB rifle in A Christmas Story). But know that often it’s the simple, smaller good gifts in regular doses that make the biggest, longest impact. Because the most lasting impression of any of the good things you give your children will be how much you enjoyed giving it to them. This is important, because when, out of love for them, you must discipline them or make a decision that displeases them, or some significant disagreement arises between you, and they’re tempted to doubt that you care about their happiness, your history of consistent, simple, memorable good gifts, given because you love to do them good, can remind them that even now you are pursuing their joy. It can become an echo of Jesus’s words: “Fear not, little flock, for it is your Father’s good pleasure to give you the kingdom” (Luke 12:32). And it will model for them that God too really does take joy in their joy, even when his discipline is “painful rather than pleasant,” since later it will yield “the peaceful fruit of righteousness to those who have been trained by it” (Hebrews 12:11). “Often it’s the simple, smaller good gifts in regular doses that make the biggest, longest impact.” If your children experience their father’s good pleasure in giving them joy, what is likely to stay with them, long after the good gifts are gone, is this: the gift you were to them. The real treasure wasn’t their father’s good things; it was their father. And in this is an invaluable parable, if our children have eyes to see. Let Your Pleasure Speak for Itself God means for your pleasure in giving your children pleasure to first speak for itself. One last brief word of practical counsel. For the most part, avoid immediately turning the moments you give gifts to your kids into a teaching moment. Don’t explain right then that what you’re doing is an illustration of Matthew 7:9–11. Let your pleasure in giving them pleasure speak for itself, and allow them the magic moment when the Holy Spirit helps them make the connection. In fact, don’t talk too much to them about your experience as such. Wait for meaningful moments, and then take them when they come. Like an early Friday morning text message to your sentimental sixteen-year-old while she’s sitting in a crowded high school classroom, forcing her to text back, “Stop! ur gonna make me cry!” Article by Jon Bloom