101 Activities For Teaching Creativity And Problem Solving Order Printed Copy

- Author: Arthur B Vangundy

- Size: 3.87MB | 410 pages

- |

Others like 101 activities for teaching creativity and problem solving Features >>

Words That Change Minds - The 14 Patterns For Mastering The Language Of Influence

7 Strategies For Wealth & Happiness

Change Your Habits, Change Your Life

Tough Times Never Last, But Tough People Do

Who Moved My Cheese

How To Influence People

-160.webp)

Better Decisions, Fewer Regrets (5 Questions To Help You Determine Your Next Move)

The Top Ten Mistakes Pastors Make

Empty Out The Negative

The Little Red Book Of Wisdom

About the Book

"101 Activities for Teaching Creativity and Problem Solving" by Arthur B. VanGundy offers a comprehensive guide for educators to enhance their students' creative thinking and problem-solving skills in the classroom. The book provides a collection of engaging activities and techniques that can be easily implemented to stimulate creativity and foster innovative solutions.

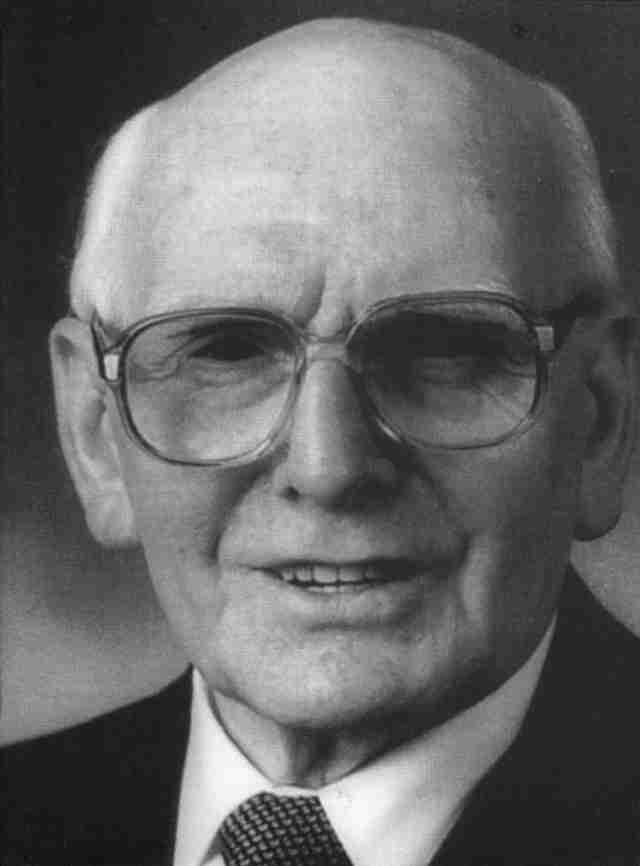

William Still

I recently read Dying to Live (Christian Focus, 1991), the autobiography of Scottish pastor William Still. I became interested in Still after reading his book The Work of the Pastor earlier this year.

The first half of Dying to Live tells about Still’s early years into young adulthood and his beginning in pastoral ministry. Still had an unsettled childhood. His parents were separated in his early years, and his father was an alcoholic. He was a sickly child who took refuge in music and became an accomplished pianist. He was part of the Salvation Army as a young man but then entered ministry in the Church of Scotland and served at the Gilcomston Church in his hometown of Aberdeen from 1945-1997.

The second half of the book deals with various aspects of Still’s pastoral ministry. Still was an evangelical. In his early ministry he worked with Billy Graham, Alan Redpath, and others in evangelistic events. With time, however, he moved away from what he came to call “evangelisticism” to develop a solid expositional ministry.

Still faced his fair share of hardships during the course of his ministry. When he moved away from pragmatic evangelistic methods, for example, more than two hundred people stopped attending his church almost overnight. In the preface, he references Martin Luther’s observation that there are three things which make a minister: study, prayer, and afflictions. He observes, “He who is not prepared to make enemies for Christ’s sake by the faithful preaching of the Word will never make lasting friends for Christ, either” (p. 93).

He describes one particularly difficult controversy early in his ministry when he confronted a group of disgruntled elders. At the end of one Sunday service, he read a statement confronting these men, which ended, “There you sit, with your heads down, guilty men. What would you say if I named you before the whole congregation? You stand condemned before God for your contempt of the Word and of his folk.” He adds, “The moment I had finished, I walked out of the pulpit. There was no last hymn—no benediction. I went right home. It was the hardest and most shocking thing I ever had to do in Gilcomston” (p. 124). That same week seven of his elders resigned and Still was called twice before his Presbytery to answer for the controversy. Yet, he endured.

Still maintains that in light of the unpleasantness one will face in the ministry that the minister of the Word must possess one quality in particular: “…I would say that this quality is courage: guts, sheer lion-hearted bravery, clarity of mind and purpose, grit. Weaklings are no use here. They have a place in the economy of God if they are not deliberate weaklings and stunted adults as Paul writes of both to the Romans and to the Corinthians. But weaklings are no use to go out and speak prophetically to men from God and declare with all compassion, as well as with faithfulness, the truth: the divine Word that cuts across all men’s worldly plans for their lives” (p. 140).

Still was a pioneer in several areas. First, he developed a pattern of preaching and teaching systematically through books of the Bible at a time when this was rarely done. He began a ministry of “consecutive Bible teaching” starting with the book of Galatians in 1947, calling this transition from “evangelisticism to systematic exposition … probably the most significant decision in my life” (p. 191).

He was also a pioneer in simplifying and integrating the ministry of the church. After noting how youth in the church were drifting away, even after extensive involvement in the church’s children’s ministry, Still writes, “I conceived the idea of ceasing all Sunday School after beginners and Primary age (seven years) and invited parents to have their children sit with them in the family pew from the age of eight” (p. 171). He laments “the disastrous dispersion of congregations by the common practice of segregating the church family into every conceivable category of division of ages, sexes, etc.” (p. 173).

Dying to Live is a helpful and encouraging work about the life and work of the minister and is to be commended to all engaged in the call of gospel ministry. As the title indicates, Still’s essential thesis is that in order to be effective in ministry the minister must suffer a series of deaths to himself (cf. John 12:24). On this he writes:

The deaths one dies before ministry can be of long duration—it can be hours and days before we minister, before the resurrection experience of anointed preaching. And then there is another death afterwards, sometimes worse than the death before. From the moment that you stand there dead in Christ and dead to everything you are and have and ever shall be and have, every breath you breathe thereafter, every thought you think, every word you say and deed you do, must be done over the top of your own corpse or reaching over it in your preaching to others. Then it can only be Jesus that comes over and no one else. And I believe that every preacher must bear the mark of that death. Your life must be signed by the Cross, not just Christ’s cross (and there is really no other) but your cross in his Cross, your particular and unique cross that no one ever died—the cross that no one ever could die but you and you alone: your death in Christ’s death (p. 136).

I recently read Dying to Live (Christian Focus, 1991), the autobiography of Scottish pastor William Still. I became interested in Still after reading his book The Work of the Pastor earlier this year.

The first half of Dying to Live tells about Still’s early years into young adulthood and his beginning in pastoral ministry. Still had an unsettled childhood. His parents were separated in his early years, and his father was an alcoholic. He was a sickly child who took refuge in music and became an accomplished pianist. He was part of the Salvation Army as a young man but then entered ministry in the Church of Scotland and served at the Gilcomston Church in his hometown of Aberdeen from 1945-1997.

The second half of the book deals with various aspects of Still’s pastoral ministry. Still was an evangelical. In his early ministry he worked with Billy Graham, Alan Redpath, and others in evangelistic events. With time, however, he moved away from what he came to call “evangelisticism” to develop a solid expositional ministry.

Still faced his fair share of hardships during the course of his ministry. When he moved away from pragmatic evangelistic methods, for example, more than two hundred people stopped attending his church almost overnight. In the preface, he references Martin Luther’s observation that there are three things which make a minister: study, prayer, and afflictions. He observes, “He who is not prepared to make enemies for Christ’s sake by the faithful preaching of the Word will never make lasting friends for Christ, either” (p. 93).

He describes one particularly difficult controversy early in his ministry when he confronted a group of disgruntled elders. At the end of one Sunday service, he read a statement confronting these men, which ended, “There you sit, with your heads down, guilty men. What would you say if I named you before the whole congregation? You stand condemned before God for your contempt of the Word and of his folk.” He adds, “The moment I had finished, I walked out of the pulpit. There was no last hymn—no benediction. I went right home. It was the hardest and most shocking thing I ever had to do in Gilcomston” (p. 124). That same week seven of his elders resigned and Still was called twice before his Presbytery to answer for the controversy. Yet, he endured.

Still maintains that in light of the unpleasantness one will face in the ministry that the minister of the Word must possess one quality in particular: “…I would say that this quality is courage: guts, sheer lion-hearted bravery, clarity of mind and purpose, grit. Weaklings are no use here. They have a place in the economy of God if they are not deliberate weaklings and stunted adults as Paul writes of both to the Romans and to the Corinthians. But weaklings are no use to go out and speak prophetically to men from God and declare with all compassion, as well as with faithfulness, the truth: the divine Word that cuts across all men’s worldly plans for their lives” (p. 140).

Still was a pioneer in several areas. First, he developed a pattern of preaching and teaching systematically through books of the Bible at a time when this was rarely done. He began a ministry of “consecutive Bible teaching” starting with the book of Galatians in 1947, calling this transition from “evangelisticism to systematic exposition … probably the most significant decision in my life” (p. 191).

He was also a pioneer in simplifying and integrating the ministry of the church. After noting how youth in the church were drifting away, even after extensive involvement in the church’s children’s ministry, Still writes, “I conceived the idea of ceasing all Sunday School after beginners and Primary age (seven years) and invited parents to have their children sit with them in the family pew from the age of eight” (p. 171). He laments “the disastrous dispersion of congregations by the common practice of segregating the church family into every conceivable category of division of ages, sexes, etc.” (p. 173).

Dying to Live is a helpful and encouraging work about the life and work of the minister and is to be commended to all engaged in the call of gospel ministry. As the title indicates, Still’s essential thesis is that in order to be effective in ministry the minister must suffer a series of deaths to himself (cf. John 12:24). On this he writes:

The deaths one dies before ministry can be of long duration—it can be hours and days before we minister, before the resurrection experience of anointed preaching. And then there is another death afterwards, sometimes worse than the death before. From the moment that you stand there dead in Christ and dead to everything you are and have and ever shall be and have, every breath you breathe thereafter, every thought you think, every word you say and deed you do, must be done over the top of your own corpse or reaching over it in your preaching to others. Then it can only be Jesus that comes over and no one else. And I believe that every preacher must bear the mark of that death. Your life must be signed by the Cross, not just Christ’s cross (and there is really no other) but your cross in his Cross, your particular and unique cross that no one ever died—the cross that no one ever could die but you and you alone: your death in Christ’s death (p. 136).

a safe place for sinners to change

Hidden sins destroy Christians because they’re hidden. Far too often, Christians wallow in the darkness, smothered by the guilt of sins that they are too ashamed to name. It’s impossible to put to death a sin you won’t confess. Which means cultivating the right environment for honesty and confession is essential in a Christian community. No issue reveals this better than the struggle against pornography and lust. In my experience, one fundamental factor in creating the right environment for intentional action, real accountability, and healthy habits of confession is the presence and demeanor of a wise pastor or mentor. The gospel presence of a leader is a powerful means of grace that helps Christians resist the hopelessness that often marks this struggle. So, what exactly is gospel presence ? “Cultivating the right environment for honesty and confession is essential in a Christian community.” By gospel , I simply mean the good news that, as sinners, we are embraced and accepted by God because of what Jesus has done for us. He lived the life that we couldn’t live. He died the death we should have died. And God raised him from the dead, triumphing over sin and death. Outside of Jesus, there is no hope. In Jesus, we have a living hope. By presence , I mean that there’s a way of being, an orientation to life and reality and others, a fundamental attitude that emanates from the core of who you are, and shapes and colors everything you do. The way you carry yourself. The impression you give. That’s what I mean by presence . And gospel presence is crucial for creating the right environment for dealing with any sin, and especially sexual sin. Six Aspects of Gospel Presence Because gospel presence is more about the way that someone carries himself than following a specific set of actions, it’s difficult to define. However, I’ve found Colossians 3:1–17 to be a fruitful place to get the feel of it. Here are six aspects of gospel presence in the passage. First, gospel presence begins with setting one’s mind on Christ (Colossians 3:1). Set your mind. Set your affection. Orient your life by Christ, who is your life. He’s the sun; everything in your life orbits around him. Second, gospel presence means putting on the new self , or the new man (Colossians 3:9–10). The fundamental contrast is between the old man (Adam), who rebelled against God, and the new Man (Jesus), who fully trusted, obeyed, and imaged God. Gospel presence means that you “put on” the new Man — that you “clothe” yourself with Jesus. And that’s a good image for it: You must wear Jesus, like a cloak. There are practices that flow out of this presence. There is an old man with his practices, and a new man with his practices. There are practices that come from and accord with sinful Adam, and practices that come from and accord with Christ. And you can’t do the practices if you don’t put on the presence. Third, gospel presence means that you are fundamentally defined by God’s love in the gospel. “Put on then, as God’s chosen ones, holy and beloved . . .” (Colossians 3:12). There are characteristics and qualities that you put on and practice because you are holy and beloved by God. He defines you. “By the grace of God I am what I am” (1 Corinthians 15:10). His grace is what makes you who and what you are. Gospel presence means that his love and grace define you, and you know it deep in your bones. Fourth, gospel presence means you are ruled by the peace of Christ (Colossians 3:15). You are firm, stable, steadfast, unshaken. You’re not tossed to and fro. When storms come, you’re planted on a rock. When chaos erupts, God’s peace still reigns in your heart. There’s a kind of stability and security that comes from knowing you’re loved by God, defined by grace, oriented by Christ, clothed with the new Man. Fifth, gospel presence means that the word of Christ dwells in you richly in all wisdom (Colossians 3:16) — not just that you read your Bible, but that there is a richness and fullness and potency to the word in your life. The Spirit of God hangs on you, and there’s a felt sense that “here’s a person who has been with God.” Gospel presence means you have the wisdom to connect the word of God to life in a way that bears fruit. Last, gospel presence means all of your practices are done in the name of the Lord Jesus (Colossians 3:17). Your actions bear his name. They testify to him and point to him and draw attention to him. “Gospel presence aims to create that graciously paradoxical environment that is safe for sinners, but not for sin.” How then does gospel presence serve honest confession and the fight against sin, and especially sexual sin? The gospel presence of a pastor or mentor is designed to create an environment that invites people to confess their sins, to be honest about their struggles, to overcome the natural aversion they have to exposing their shame. In other words, gospel presence aims to create that graciously paradoxical environment that is safe for sinners, but not for sin. They are welcome; their sin is not. And thus there are two key elements of gospel presence that help to create such an environment: compassionate stability and focused hostility . Compassionate Stability Compassionate stability means that a mentor aims to de-escalate the situation by leaning into the mess. Often people who are wrecked by sexual sin are filled with shame, fear of exposure, anxiety about future failure, and hopelessness about the possibility of change. They think, “If I admit out loud what I’ve done or seen or thought, then everyone will be so disgusted by me that they’ll reject me.” Such passions overwhelm a Christian’s desire to be honest about his struggle. The compassionate stability of gospel presence is meant to calm the broken, anxious, and fearful sinner. Compassionate stability leans into the mess. The aim is to communicate that God is for them and with them through the fact that you as the mentor are for them and with them. This stability and calmness is not stoic; you should feel deeply for the people to whom you minister. But your passions and emotions are, by God’s grace, under your control and direction so that you can willingly and compassionately lean into their sin. Broken sinners need to know that you’re not recoiling in horror at them, no matter what they confess. They need to feel that you (and therefore God) are with them and passionately committed to their good. Compassionate stability communicates that we are not afraid of a person’s sin. No matter how dark the darkness, the grace of Jesus can reach deeper. There may still be consequences for certain sins (especially any sins that are also crimes). But compassionate stability communicates that, no matter the consequences, Jesus is real, and he will be with you as you bring your darkness into the light. IF GOD IS FOR US Compassionate stability seeks to embody the deep truths of the gospel reflected in passages like Romans 8:31–39. This passage captures the spirit of compassionate stability as well as any in the Bible. If God is for us, who can be against us (Romans 8:31)? God didn’t spare his own Son but gave him up for us, and will therefore freely and graciously give us everything (8:32). No one can bring a charge against us, because God himself has justified and approved of us (8:33). No one can condemn us, because Christ was crucified for us and raised for us and is now interceding for us (8:34). Nothing can separate us from the love of Christ — not tribulation, or distress, or persecution, or famine, or nakedness, or danger, or sword (8:35). God’s all-conquering love means that every possible obstacle to our ultimate good makes us more than conquerors (8:37). Death, life, angels, rulers, present things, future things, powers, height, depth, anything else in all creation — none of these can separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord (8:38–39). That’s how committed God is to our good, and that’s what faithful pastors and mentors communicate to their people. When nerves are on edge, when passions and fears are raging, compassionate stability plants itself in Romans 8 and brings a deep and settled sense of Spirit-wrought peace and calm. Romans 8 empowers us to be stable and compassionate, and compassionate stability makes an environment that is safe for sinners. Focused Hostility But there’s another aspect to the right environment. Embracing broken sinners entails a violent hostility toward their sin. If we’re really committed to someone’s good, then we will hate and resist those things that are harmful to them. And so it’s necessary to combine compassionate stability with focused hostility . Focused hostility is still under control, but it includes a relentlessness and patience in exposing and killing sin. Without this focused hostility toward sin, we may find ourselves reluctant to challenge people to pursue holiness. Comforting may turn into coddling. But part of being a wise and faithful counselor to others means communicating the gravity of sin. The Bible minces no words about the consequences of making peace with ongoing sin. “If you live according to the flesh you will die [eternally]” (Romans 8:13). Those who practice the works of the flesh will not inherit the kingdom of God (Galatians 5:19–21; 1 Corinthians 6:9–10). And the Bible uses intense and violent language to describe how we ought to resist sin: put it to death (Colossians 3:5–6; Romans 8:13); tear it out (Matthew 5:29); cut it off (Matthew 5:30); flee sexual immorality and youthful passions (1 Corinthians 6:18; 2 Timothy 2:22). These words of violence and intensity remind us that we can’t make peace with our sin, because the Holy Spirit will never make peace with our sin. “Gospel presence aims to communicate both that God is for you, and that your sin is not welcome.” Gospel presence aims to communicate both that God is for you, and that your sin is not welcome. A person doesn’t need to clean himself up to come to us or to God; he can come as he is. But we are committed to not letting him stay as he is. And so, with our demeanor and our words, we say, “I am for you; I’m leaning in; I’m not recoiling because of what you just confessed. I love you and I’m with you and I’m for you because God loves you and is with you and is for you. And I am so for you that I will never make peace with your sin. I will call you to put it to death, to cut it off, to flee from it.” Gospel presence says to a sinner, sexual or otherwise, “I love you, I’m for you, I’m with you. Now let’s kill it.”