Others like the greatness of the soul Features >>

Epic Battles Of The Last Days

The Dark Side Of The Supernatural

Angels In The Realms Of Heaven - The Reality Of Angelic Ministry Today

Tasting The Powers Of The Age To Come

The Last Hours Of Jesus - From Gethsemane To Golgotha

-160.webp)

The Genesis 6 Conspiracy (How Secret Societies And The Descendants Of Giants Plan To Enslave Humankind)

The Road To Hell

Death And The Life After

Angels On Assignment As Told By Roland H. Buck

Resurrection And Judgement

About the Book

"The Greatness of the Soul" explores the importance of the soul and its eternal significance. John Bunyan examines the value of the soul and the necessity of spiritual growth and salvation. Through thought-provoking allegories and powerful teachings, Bunyan emphasizes the soul's greatness and the need for individuals to prioritize their spiritual well-being.

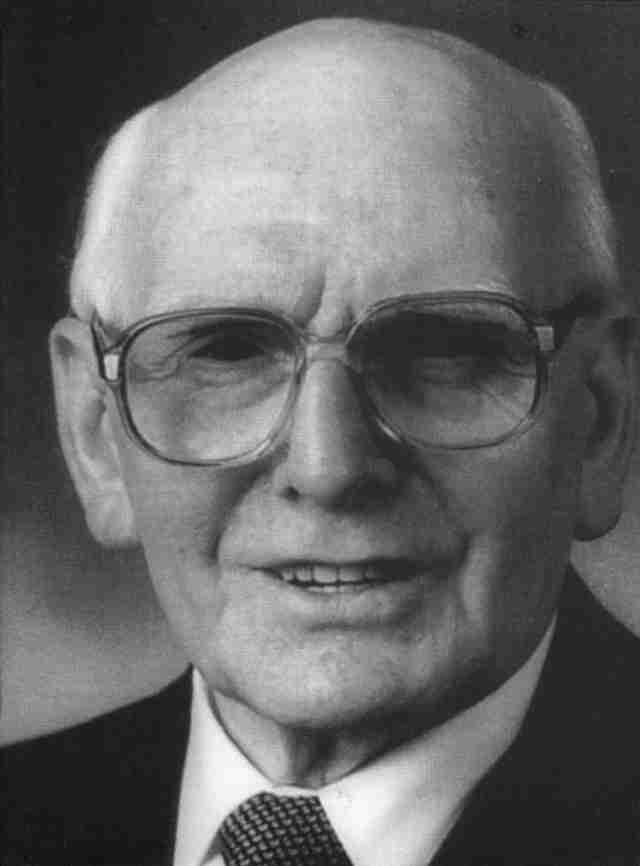

William Still

I recently read Dying to Live (Christian Focus, 1991), the autobiography of Scottish pastor William Still. I became interested in Still after reading his book The Work of the Pastor earlier this year.

The first half of Dying to Live tells about Still’s early years into young adulthood and his beginning in pastoral ministry. Still had an unsettled childhood. His parents were separated in his early years, and his father was an alcoholic. He was a sickly child who took refuge in music and became an accomplished pianist. He was part of the Salvation Army as a young man but then entered ministry in the Church of Scotland and served at the Gilcomston Church in his hometown of Aberdeen from 1945-1997.

The second half of the book deals with various aspects of Still’s pastoral ministry. Still was an evangelical. In his early ministry he worked with Billy Graham, Alan Redpath, and others in evangelistic events. With time, however, he moved away from what he came to call “evangelisticism” to develop a solid expositional ministry.

Still faced his fair share of hardships during the course of his ministry. When he moved away from pragmatic evangelistic methods, for example, more than two hundred people stopped attending his church almost overnight. In the preface, he references Martin Luther’s observation that there are three things which make a minister: study, prayer, and afflictions. He observes, “He who is not prepared to make enemies for Christ’s sake by the faithful preaching of the Word will never make lasting friends for Christ, either” (p. 93).

He describes one particularly difficult controversy early in his ministry when he confronted a group of disgruntled elders. At the end of one Sunday service, he read a statement confronting these men, which ended, “There you sit, with your heads down, guilty men. What would you say if I named you before the whole congregation? You stand condemned before God for your contempt of the Word and of his folk.” He adds, “The moment I had finished, I walked out of the pulpit. There was no last hymn—no benediction. I went right home. It was the hardest and most shocking thing I ever had to do in Gilcomston” (p. 124). That same week seven of his elders resigned and Still was called twice before his Presbytery to answer for the controversy. Yet, he endured.

Still maintains that in light of the unpleasantness one will face in the ministry that the minister of the Word must possess one quality in particular: “…I would say that this quality is courage: guts, sheer lion-hearted bravery, clarity of mind and purpose, grit. Weaklings are no use here. They have a place in the economy of God if they are not deliberate weaklings and stunted adults as Paul writes of both to the Romans and to the Corinthians. But weaklings are no use to go out and speak prophetically to men from God and declare with all compassion, as well as with faithfulness, the truth: the divine Word that cuts across all men’s worldly plans for their lives” (p. 140).

Still was a pioneer in several areas. First, he developed a pattern of preaching and teaching systematically through books of the Bible at a time when this was rarely done. He began a ministry of “consecutive Bible teaching” starting with the book of Galatians in 1947, calling this transition from “evangelisticism to systematic exposition … probably the most significant decision in my life” (p. 191).

He was also a pioneer in simplifying and integrating the ministry of the church. After noting how youth in the church were drifting away, even after extensive involvement in the church’s children’s ministry, Still writes, “I conceived the idea of ceasing all Sunday School after beginners and Primary age (seven years) and invited parents to have their children sit with them in the family pew from the age of eight” (p. 171). He laments “the disastrous dispersion of congregations by the common practice of segregating the church family into every conceivable category of division of ages, sexes, etc.” (p. 173).

Dying to Live is a helpful and encouraging work about the life and work of the minister and is to be commended to all engaged in the call of gospel ministry. As the title indicates, Still’s essential thesis is that in order to be effective in ministry the minister must suffer a series of deaths to himself (cf. John 12:24). On this he writes:

The deaths one dies before ministry can be of long duration—it can be hours and days before we minister, before the resurrection experience of anointed preaching. And then there is another death afterwards, sometimes worse than the death before. From the moment that you stand there dead in Christ and dead to everything you are and have and ever shall be and have, every breath you breathe thereafter, every thought you think, every word you say and deed you do, must be done over the top of your own corpse or reaching over it in your preaching to others. Then it can only be Jesus that comes over and no one else. And I believe that every preacher must bear the mark of that death. Your life must be signed by the Cross, not just Christ’s cross (and there is really no other) but your cross in his Cross, your particular and unique cross that no one ever died—the cross that no one ever could die but you and you alone: your death in Christ’s death (p. 136).

I recently read Dying to Live (Christian Focus, 1991), the autobiography of Scottish pastor William Still. I became interested in Still after reading his book The Work of the Pastor earlier this year.

The first half of Dying to Live tells about Still’s early years into young adulthood and his beginning in pastoral ministry. Still had an unsettled childhood. His parents were separated in his early years, and his father was an alcoholic. He was a sickly child who took refuge in music and became an accomplished pianist. He was part of the Salvation Army as a young man but then entered ministry in the Church of Scotland and served at the Gilcomston Church in his hometown of Aberdeen from 1945-1997.

The second half of the book deals with various aspects of Still’s pastoral ministry. Still was an evangelical. In his early ministry he worked with Billy Graham, Alan Redpath, and others in evangelistic events. With time, however, he moved away from what he came to call “evangelisticism” to develop a solid expositional ministry.

Still faced his fair share of hardships during the course of his ministry. When he moved away from pragmatic evangelistic methods, for example, more than two hundred people stopped attending his church almost overnight. In the preface, he references Martin Luther’s observation that there are three things which make a minister: study, prayer, and afflictions. He observes, “He who is not prepared to make enemies for Christ’s sake by the faithful preaching of the Word will never make lasting friends for Christ, either” (p. 93).

He describes one particularly difficult controversy early in his ministry when he confronted a group of disgruntled elders. At the end of one Sunday service, he read a statement confronting these men, which ended, “There you sit, with your heads down, guilty men. What would you say if I named you before the whole congregation? You stand condemned before God for your contempt of the Word and of his folk.” He adds, “The moment I had finished, I walked out of the pulpit. There was no last hymn—no benediction. I went right home. It was the hardest and most shocking thing I ever had to do in Gilcomston” (p. 124). That same week seven of his elders resigned and Still was called twice before his Presbytery to answer for the controversy. Yet, he endured.

Still maintains that in light of the unpleasantness one will face in the ministry that the minister of the Word must possess one quality in particular: “…I would say that this quality is courage: guts, sheer lion-hearted bravery, clarity of mind and purpose, grit. Weaklings are no use here. They have a place in the economy of God if they are not deliberate weaklings and stunted adults as Paul writes of both to the Romans and to the Corinthians. But weaklings are no use to go out and speak prophetically to men from God and declare with all compassion, as well as with faithfulness, the truth: the divine Word that cuts across all men’s worldly plans for their lives” (p. 140).

Still was a pioneer in several areas. First, he developed a pattern of preaching and teaching systematically through books of the Bible at a time when this was rarely done. He began a ministry of “consecutive Bible teaching” starting with the book of Galatians in 1947, calling this transition from “evangelisticism to systematic exposition … probably the most significant decision in my life” (p. 191).

He was also a pioneer in simplifying and integrating the ministry of the church. After noting how youth in the church were drifting away, even after extensive involvement in the church’s children’s ministry, Still writes, “I conceived the idea of ceasing all Sunday School after beginners and Primary age (seven years) and invited parents to have their children sit with them in the family pew from the age of eight” (p. 171). He laments “the disastrous dispersion of congregations by the common practice of segregating the church family into every conceivable category of division of ages, sexes, etc.” (p. 173).

Dying to Live is a helpful and encouraging work about the life and work of the minister and is to be commended to all engaged in the call of gospel ministry. As the title indicates, Still’s essential thesis is that in order to be effective in ministry the minister must suffer a series of deaths to himself (cf. John 12:24). On this he writes:

The deaths one dies before ministry can be of long duration—it can be hours and days before we minister, before the resurrection experience of anointed preaching. And then there is another death afterwards, sometimes worse than the death before. From the moment that you stand there dead in Christ and dead to everything you are and have and ever shall be and have, every breath you breathe thereafter, every thought you think, every word you say and deed you do, must be done over the top of your own corpse or reaching over it in your preaching to others. Then it can only be Jesus that comes over and no one else. And I believe that every preacher must bear the mark of that death. Your life must be signed by the Cross, not just Christ’s cross (and there is really no other) but your cross in his Cross, your particular and unique cross that no one ever died—the cross that no one ever could die but you and you alone: your death in Christ’s death (p. 136).

Will Hell Really Last Forever

I am almost ashamed to admit that such a tiny bird should have been used to frighten a grown man. But in this case, I was right to tremble. The image in my mind’s eye of that little bird descending from above, flitting back and forth, hopping up and down upon the immensity of sand. What a horror to see it flap away with so little a grain only to expect its return so many lifetimes later. All to remember that it would be all irrelevant anyways. Thomas Watson gave the illustration, preaching on the fate of those who worshiped the beast in Revelation 14:11, which says, “The smoke of their torment goes up forever and ever, and they have no rest, day or night. . .” It cannot be forgotten: Oh eternity! If all the body of earth and sea were turned to sand, and all the air up to the starry heaven were nothing but sand, and a little bird should come every thousand years, and fetch away in her bill but the tenth part of a grain of all that heap of sand, what numberless years would be spent before that vast heap of sand would be fetched away! Yet, if at the end of all that time, the sinner might come out of hell, there would be some hope; but that word “Ever” breaks the heart. “The smoke of their torment ascendeth up for ever and ever.” After coming and going every thousand years, carrying away one of the smallest grains of the innumerable amount of sand, this hour glass would finally drain and the banished would be no closer to the end than when they first began. That word which should make the most apathetic among the unforgiven weep, the strongest sweat blood, the youngest curl into the fetal position, the oldest break into madness to hear its footsteps so near, shook me. Who can rightly fathom it? Forever. Ghosts Reading over Shoulders But is it true? Do those in hell suffer eternal conscious punishment? The church throughout its two-thousand-year history has thought so, but many today do not. And we shouldn’t wonder why: this is personal to us. I write keenly aware that the memories of deceased loved ones who departed in apparent unbelief hover over shoulders reading along. What of him? What of her? we wonder. Although he was one of the first notable evangelicals of the previous generation to contradict the historic conception of hell, we must all adopt the final question John Stott considers, I find the concept [of eternal conscious punishment in hell] intolerable and do not understand how people can live with it without either cauterizing their feelings or cracking under the strain. But our emotions are a fluctuating, unreliable guide to truth and must not be exalted to the place of supreme authority in determining it. As a committed Evangelical, my question must be — and is — not what does my heart tell me, but what does God’s word say? So what does God’s word say? Nothing different from what the church has overwhelmingly held over its two millennia. Three Objections Of all topics that feel crude to abridge, this must be atop the list. Much has been written on this topic that fly past the scope of this article. Resources I found helpful include Hell Under Fire, Grudem’s Systematic Theology, and chapters in Gagging of God (13) and Let the Nations Be Glad (4). That said, I would like to give brief answers to common challenges to those who believe those in hell will ultimately be annihilated. 1. Does ‘Eternal’ Mean Forever? Conditionalists (those who believe the wicked will eventually cease to be, based on the fact that the soul is not inherently immortal but becomes so as they meet certain conditions, and in particular through union with Christ) and annihilationists (those who believe the wicked will cease to be because, although the soul would have otherwise prolonged, God finally annihilates them in judgement) both believe that hell is not endless punishment for the wicked. In proving this, they both point out that “eternal” does not always mean everlasting. They argue that both in the Hebrew and Greek, the corresponding words we often translate “eternal” have elasticity to mean “forever” as well as other things, such as “age to come,” which they argue could last forever or not. One of the strongest reasons this is unpersuasive (without going text by text) is that some of the biblical passages in question speak in the same breath of both the eternality of the righteous (which we don’t question) and the eternality of the unrighteous (which some do). In other words, the life that the righteous enjoy is parallel to the punishment the wicked suffer. Hell lasts as long as heaven. For example, Daniel speaks of those who will awake from death: “Many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life, and some to shame and everlasting contempt” (Daniel 12:2). This idea is carried through into the New Testament by Jesus in Matthew 25 (which many think is, by itself, decisive on the matter) when he teaches the parallel fates of the righteous and the unrighteous: “These will go away into eternal punishment, but the righteous into eternal life” (Matthew 25:46). Furthermore, the book of Revelation displays the same thing, utilizing the most emphatic language afforded in Greek to mean forever: “for ever and ever” (eis aiōnas aiōnōn), as in the text already cited with the little bird: If anyone worships the beast and its image and receives a mark on his forehead or on his hand, he also will drink the wine of God’s wrath, poured full strength into the cup of his anger, and he will be tormented with fire and sulfur in the presence of the holy angels and in the presence of the Lamb. And the smoke of their torment goes up forever and ever, and they have no rest, day or night, these worshipers of the beast and its image, and whoever receives the mark of its name. (Revelation 14:9–11) The same description is employed to describe the everlasting suffering of Satan and his demons: “The devil who had deceived them was thrown into the lake of fire and sulfur where the beast and the false prophet were, and they will be tormented day and night forever and ever” (Revelation 20:10). And this, again, is parallel to the righteous’ fate later in the book: “They will need no light of lamp or sun, for the Lord God will be their light, and they will reign forever and ever” (Revelation 22:5). Heaven and hell will cease together. 2. Will the Wicked Cease to Exist? Scripture often employs terms such as “destruction” (Matthew 10:18), “perishing” (John 3:16), and “death” (Revelation 20:14) to describe the judgment of God on those in hell. These terms, some argue, entail complete annihilation, not continuing anguish. As Stott memorably put it, “It would seem strange . . . if people who are said to suffer destruction are in fact not destroyed; and as you put it, it is difficult to imagine a perpetually inconclusive process of perishing.” In response, D.A. Carson replies, “Stott’s conclusion (‘It would seem strange . . . if people who are said to suffer destruction are in fact not destroyed’) is memorable, but useless as an argument, because it is merely tautologous: of course those who suffer destruction are destroyed. But it does not follow that those who suffer destruction cease to exist. Stott has assumed his definition of “destruction” in his epigraph.” So what does it mean then? I have a family member whose car recently started on fire and was completely destroyed. It was totaled and rendered useless. They sent me a picture of it — its frame, and doors, still were intact though completely black. The mirror hung limp. The front mirror was incinerated. The hood melted and the wires and engine exposed. It was ruined, but did not cease to be. But aren’t the wicked described as being thrown into fire — something that utterly consumes? No, for “they will have no rest day or night” (Revelation 14:11). The devil, his demons, and the “children of wrath” who followed him, will, like the burning bush and hell’s worm that does not die, burn yet not be consumed. They will beg any who will listen to give but a drop of water on their tongue to relieve their anguish from the flames (Luke 16:24), their “place of torment” (Luke 16:28). “In that place there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth” (Matthew 13:50), not silence or the mere roaring of a fire. 3. Does the Punishment Fit the Crime? Another critique, more philosophically argued, is that it is unjust to earn an infinite duration of punishment for finite sins. The punishment doesn’t match such a crime, it is alleged. To this, we may respond as follows. Crimes Against the Infinite God A man can commit such gross crimes against his fellow humans that he could earn ten life sentences for ten minutes of mayhem. And these are but sins against men. Can the idea of sinning against God — and not only in a moment but for one’s whole lifetime — not merit eternal damnation when one sin justly plunged the world into death and darkness? Edwards is often cited as arguing this. John Piper summarizes, “The essential thing is that degrees of blameworthiness come not from how long you offend dignity, but from how high the dignity is that you offend” (Let the Nations Be Glad, 127). We sin against a God infinitely worthy of obedience, infinite in glory, infinite in purity. No dignity is higher and no transgression viler. It reveals much that we see more problems with the punishment than the crime. Eternal Sins? Another reason this is righteous is that there is good reason to understand sins as being eternal, in at least two senses. First, Jesus spoke of an eternal (not finite) sin (Mark 3:29), a sin that “will not be forgiven, either in this age or in the age to come” (Matthew 12:32). And sins not explicitly named as this eternal sin, result in eternal destruction (2 Thessalonians 1:9), eternal judgment (Hebrews 6:2), eternal punishment (Matthew 25:46), and eternal fire (Matthew 25:41) which undermines our finite categories. Second, sins of the damned can be eternal in that sinners continue to sin throughout eternity. John Stott admitted that eternal conscious punishment would be much more sensible to him if “perhaps (as has been argued) the impenitence of the lost also continues throughout eternity.” Two texts seem to indicate this. The first, Revelation 22:10–11: “Let him who does wrong continue to do wrong; let him who is vile continue to be vile; let him who does right continue to do right; and let him who is holy continue to be holy.” If the holy practice holiness in anticipation of continuing in perfect holiness, will not the ungodly continue to spiral in evil throughout eternity? Will they suddenly love God with all their souls in hell? The answer is clear enough in Revelation 16:8–11, where people under God’s judgment “gnawed their tongues in anguish and cursed the God of heaven for their pain and sores. They did not repent of their deeds.” Should They Not Go Free? More on the offensive, Carson asks the necessary question, “One might reasonably wonder why, if people pay for their sins in hell before they are annihilated, they cannot be released into heaven, turning hell into purgatory. Alternatively, if the sins have not yet been paid for, why should they be annihilated?” King Who Emptied the Desert A bird could not, by the painstaking removal of a world full of sand, move us one step closer to eternity with God. Time will not amend all wounds, nor stop God’s righteous punishment. Nor will death hide the wicked, though they seek annihilation, calling on the mountains to crush them to hide them from Christ’s wrath (Revelation 6:15–17). But what a little bird could not accomplish, a Lamb has. At the pinnacle of his anguish, he cried, “My God, my God why have you forsaken me” so that those who repent and believe in him might not “suffer the punishment of eternal destruction, away from the presence of the Lord and from the glory of his might” (2 Thessalonians 1:9). Here alone can the cup of eternal judgment be drained on behalf of sinners. There is an escape from eternal punishment. Although we rightfully feel unceasing anguish and great sorrow for those who never hide beneath the cross on this side of eternity (Romans 9:1–3), even this anguish will not last. We shall celebrate God’s eternal triumph over evil forever: “Once more they cried out, ‘Hallelujah! The smoke from her goes up forever and ever’” (Revelation 19:3). Christ Jesus our Savior is worthy of eternal praise because he endured, for us, the righteous judgment that would have been ours for eternity. Article by Greg Morse