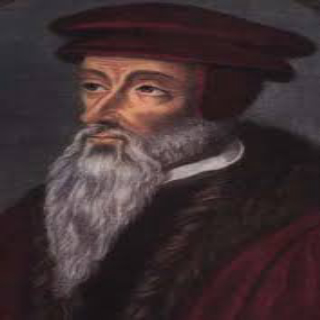

Others like the god i never knew Features >>

About the Book

"The God I Never Knew" by Robert Morris explores the person and work of the Holy Spirit, emphasizing the importance of developing a relationship with Him in order to experience a deeper connection with God. Morris delves into the power and presence of the Holy Spirit, as well as ways to cultivate intimacy with Him through prayer, worship, and obedience. Ultimately, the book encourages readers to embrace the Holy Spirit as a vital part of their Christian journey and find greater joy and fulfillment in their faith.

John Calvin

we cannot cling to bitterness and god

Forgiveness . Even the word can make us bristle. Past wounds instinctively spring to mind, making forgiveness feel impossible (or at least unnatural). What feels natural is dwelling on the horrible things that others have done to us, rehearsing their wrongs and plotting our retaliation, if only in our imagination. I know. I have nursed my anger as I have lingered over the ways people have hurt me. A close friend who ended our long-standing relationship over a misunderstanding. A woman whom I mentored for years who slandered me to others. My husband who unexpectedly left me for someone else. The doctor whose careless mistake ended my son’s life. “We cannot hold on to bitterness and hold on to God.” I remember sitting in a counselor’s office, talking about a deep betrayal. When the counselor mentioned forgiveness, I was furious. It felt like he was suggesting I offer that person a “get out of jail free” card, which was unthinkable after all I had suffered. Just hearing the word made me angry. Why should I forgive? Especially when the person didn’t even seem sorry. But as my counselor unpacked the biblical principles of forgiveness, I couldn’t ignore his words. I realized I had not fully understood what forgiveness was — and what it was not. What Forgiveness Is and Is Not There are many definitions of forgiveness, but a simple one is to surrender the right to hurt others in response to the way they’ve hurt us . Forgiveness means refusing to retaliate or hold bitterness against people for the ways they have wounded us. It is a unilateral act — not conditional on the person being repentant or even willing to acknowledge what they’ve done. Forgiveness is not saying that sin doesn’t matter. It is not approving of what the other person has done, minimizing the offense, or denying we’ve been wronged. Forgiveness is acknowledging that the other person has sinned against us and may never be able to make it right. The apostle Paul writes, “Be kind to one another, tenderhearted, forgiving one another, as God in Christ forgave you ” (Ephesians 4:32). If God in Christ forgave us, then forgiving someone cannot mean diminishing the wrong they’ve done. God could never do that with sin and remain just. Forgiveness doesn’t always mean reconciliation or restoration. And it does not require restoring trust or inviting the people who hurt us back into a relationship. Forgiveness is unconditional, but meaningful reconciliation and restoration are conditional (in the gospel and in human relationships) on the offender’s genuine repentance, humble willingness to accept the consequences of his actions, and a desire by both parties to work on the relationship. Forgiving people also doesn’t mean they won’t experience consequences for their sin. When we forgive them, however, we leave those consequences to God, who says, “Vengeance is mine, I will repay” (Romans 12:19). This doesn’t mean we may not pursue legal action, if warranted, against someone who has hurt us. In certain circumstances, that may be vital for the rehabilitation of the offender or for protecting other potential victims. Forgiveness is costly. In the Bible, it involves shedding blood (Hebrews 9:22). Sacrifice. Death. Honestly, the first step of forgiveness still often feels like death. I want to cling to my right to be angry and often resent being asked to give that up. It all seems so unfair. My flesh still demands some type of retribution. My resistance shows me I need God’s help to understand forgiveness and to truly forgive. Where Do We Begin? I have often had to say, Lord, I don’t want to forgive now, but could you make me willing to forgive? You have forgiven all my sins and I know anything I forgive others is small by comparison (Matthew 18:21–35). But I cannot do this without you. Please help me. Often, I have to repeat this prayer until God changes my heart. When he does, he usually helps me see the wounds of the person who has hurt me — wounds that do not diminish, justify, or excuse the offense, but that do soften my attitude toward the person. Once I am engaged in wanting to forgive, I begin the process of forgiveness by naming what has happened and all the negative repercussions from the person’s actions and words. I include everything. What I’ve lost. What’s been hard. How it’s made me feel. I want to know what I’m letting go of before I forgive so I can move forward, knowing I have counted the cost. For most offenses, forgiveness is both an initial decision to let go of bitterness as well as a long, ongoing process. When offenses come to mind and painful memories resurface, I must intentionally stop rehearsing them and ask the Lord to help me release those thoughts and practice forgiveness. Why Forgiveness Is Vital to Joy For years I didn’t realize the importance of forgiveness and somehow assumed it was optional; now I see it as a command. “As the Lord has forgiven you,” Colossians 3:13 says, “so you also must forgive.” So to truly forgive those who have wronged us, we must first receive God’s forgiveness, acknowledging our need before him, which empowers us to forgive others. Christian forgiveness is vertical before it is horizontal. Throughout Scripture, our Lord intertwines his forgiveness of us with our forgiveness of others (Matthew 6:14–15). And like all of his commands, it is always for our good. “Joy and sorrow often coexist, but joy and bitterness cannot.” Forgiving those who have hurt us sets us free. It keeps bitterness from taking root, bitterness that would defile us and everyone around us (Ephesians 4:31). When we cling to resentment, we unknowingly give our offender ongoing power over our hearts, which keeps us enslaved to our anger. This prison we have created pulls us away from our Lord because we cannot hold on to bitterness and hold on to God. Correspondingly, forgiving those who have wronged us releases the hold of bitterness on us. God, who has forgiven our enormous debt, gives us the power to forgive others. It is his power, not ours. This is the miracle of Christian forgiveness: when we forgive, Christ does something profound in us and for us. Those wounds inflicted by others firmly graft us into Christ, the vine, and his life flows all the more powerfully through us. The process unleashes God’s power in our lives in an unparalleled way, making forgiveness one of the most life-changing steps we ever take. Forgiveness, Freedom, and Peace Joy and sorrow often coexist, but joy and bitterness cannot. Bitterness and unforgiveness rob our lives of vitality, peace, and the refreshing joy of God’s presence. We see the power of forgiveness and grace in the lives of Joseph (Genesis 50:15–21) and Job (Job 42:7–10), who both forgave those who wronged them. And we see the hold of unforgiveness and rage on others like Joash, who murdered the priest who disagreed with him (2 Chronicles 24:20–22), and even on Jonah, who was angry at God’s compassion (Jonah 4:1–3). Being able to forgive not only changes our present; it changes our future. When we forgive, we can begin walking in freedom and joy. I don’t know where you are in your journey of forgiveness. Perhaps the wound for you is still fresh, and you need time to process all that’s happened. Maybe you’ve been holding on to bitterness for a long time, and God is asking you to let go. If that’s you, I encourage you to pray. To trust God. To forgive your offender. You won’t regret it. And after you have forgiven, after you’ve been released from the prison of bitterness, you may be amazed at how quickly God begins to flood your life with the joy and peace you lost.

-160.webp)

%20%7B%20%5Bnative%20code%5D%20%7D-160.webp)

-480.webp)