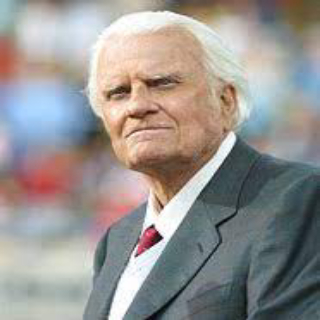

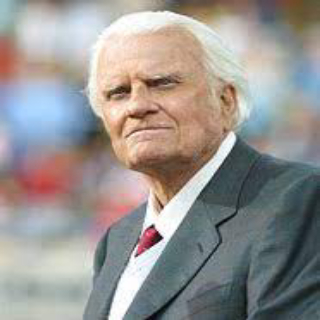

Billy Graham

Billy Graham (born November 7, 1918, Charlotte, North Carolina, U.S.—died February 21, 2018, Montreat, North Carolina), American evangelist whose large-scale preaching missions, known as crusades, and friendship with numerous U.S. presidents brought him to international prominence.

Conversion and early career

The son of a prosperous dairy farmer, Billy Graham grew up in rural North Carolina. In 1934, while attending a revival meeting led by the evangelist Mordecai Ham, he underwent a religious experience and professed his “decision for Christ.” In 1936 he left his father’s dairy farm to attend Bob Jones College (now Bob Jones University), then located in Cleveland, Tennessee, but stayed for only a semester because of the extreme fundamentalism of the institution. He transferred to Florida Bible Institute (now Trinity College), near Tampa, graduated in 1940, and was ordained a minister by the Southern Baptist Convention. Convinced that his education was deficient, however, Graham enrolled at Wheaton College in Illinois. While at Wheaton, he met and married (1943) Ruth Bell, daughter of L. Nelson Bell, a missionary to China.

By the time Graham graduated from Wheaton in 1943, he had developed the preaching style for which he would become famous—a simple, direct message of sin and salvation that he delivered energetically and without condescension. “Sincerity,” he observed many years later, “is the biggest part of selling anything, including the Christian plan of salvation.” After a brief and undistinguished stint as pastor of Western Springs Baptist Church in the western suburbs of Chicago, Graham decided to become an itinerant evangelist. He joined the staff of a new organization called Youth for Christ in 1945 and in 1947 served as president of Northwestern Bible College in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Evangelism

Graham’s emergence as an evangelist came at a propitious moment for 20th-century Protestants. Protestantism in the United States was deeply divided as a result of controversies in the 1920s between fundamentalism and modernism (a movement that applied scholarly methods of textual and historical criticism to the study of the Bible). The public image of fundamentalists was damaged by the Scopes Trial of 1925, which concerned the teaching of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution in public schools in Tennessee; in his writings about the trial, the journalist and social critic H.L. Mencken successfully portrayed all fundamentalists as uneducated country bumpkins. In response to these controversies, most fundamentalists withdrew from the established Protestant denominations, which they regarded as hopelessly liberal, and retreated from the larger society, which they viewed as both corrupt and corrupting. Although Graham remained theologically conservative, he refused to be sectarian like other fundamentalists. Seeking to dissociate himself from the image of the stodgy fundamentalist preacher, he seized on the opportunity presented by new media technologies, especially radio and television, to spread the message of the gospel.

In the late 1940s Graham’s fellow evangelist in Youth for Christ, Charles Templeton, challenged Graham to attend seminary with him so that both preachers could shore up their theological knowledge. Graham considered the possibility at length, but in 1949, while on a spiritual retreat in the San Bernardino Mountains of southern California, he decided to set aside his intellectual doubts about Christianity and simply “preach the gospel.” After his retreat, Graham began preaching in Los Angeles, where his crusade brought him national attention. He acquired this new fame in no small measure because newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, impressed with the young evangelist’s preaching and anticommunist rhetoric, instructed his papers to “puff Graham.” The huge circus tent in which Graham preached, as well as his own self-promotion, lured thousands of curious visitors—including Hollywood movie stars and gangsters—to what the press dubbed the “canvas cathedral” at the corner of Washington and Hill streets. From Los Angeles, Graham undertook evangelistic crusades around the country and the world, eventually earning international renown.

Despite his successes, Graham faced criticism from both liberals and conservatives. In New York City in 1954 he was received warmly by students at Union Theological Seminary, a bastion of liberal Protestantism; nevertheless, the theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, a professor at Union and one of the leading Protestant thinkers of the 20th century, had little patience for Graham’s simplistic preaching. On the other end of the theological spectrum, fundamentalists such as Bob Jones, Jr., Carl McIntire, and Jack Wyrtzen never forgave Graham for cooperating with the Ministerial Alliance, which included mainline Protestant clergy, in the planning and execution of Graham’s storied 16-week crusade at Madison Square Garden in New York in 1957. Such cooperation, however, was part of Graham’s deliberate strategy to distance himself from the starchy conservatism and separatism of American fundamentalists. His entire career, in fact, was marked by an irenic spirit.

Graham, by his own account, enjoyed close relationships with several American presidents, from Dwight Eisenhower to George W. Bush. (Although Graham met with Harry Truman in the Oval Office, the president was not impressed with him.) Despite claiming to be apolitical, Graham became politically close to Richard Nixon, whom he had befriended when Nixon was Eisenhower’s vice president. During the 1960 presidential campaign, in which Nixon was the Republican nominee, Graham met in Montreaux, Switzerland, with Norman Vincent Peale and other Protestant leaders to devise a strategy to derail the campaign of John F. Kennedy, the Democratic nominee, in order to secure Nixon’s election and prevent a Roman Catholic from becoming president. Although Graham later mended relations with Kennedy, Nixon remained his favourite politician; indeed, Graham all but endorsed Nixon’s reelection effort in 1972 against George McGovern. As Nixon’s presidency unraveled amid charges of criminal misconduct in the Watergate scandal, Graham reviewed transcripts of Oval Office tape recordings subpoenaed by Watergate investigators and professed to be physically sickened by his friend’s use of foul language.

Legacy of Billy Graham

Graham’s popular appeal was the result of his extraordinary charisma, his forceful preaching, and his simple, homespun message: anyone who repents of sins and accepts Jesus Christ will be saved. Behind that message, however, stood a sophisticated organization, the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, incorporated in 1950, which performed extensive advance work in the form of favourable media coverage, cooperation with political leaders, and coordination with local churches and provided a follow-up program for new converts. The organization also distributed a radio program, Hour of Decision, a syndicated newspaper column, “My Answer,” and a magazine, Decision. Although Graham pioneered the use of television for religious purposes, he always shied away from the label “televangelist.” During the 1980s, when other television preachers were embroiled in sensational scandals, Graham remained above the fray, and throughout a career that spanned more than half a century few people questioned his integrity. In 1996 Graham and his wife received the Congressional Gold Medal of Honor, the highest civilian award bestowed by the United States, and in 2001 he was made an Honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (KBE). Graham concluded his public career with a crusade in Queens, New York, in June 2005.

Graham claimed to have preached in person to more people than anyone else in history, an assertion that few would challenge. His evangelical crusades around the world, his television appearances and radio broadcasts, his friendships with presidents, and his unofficial role as spokesman for America’s evangelicals made him one of the most recognized religious figures of the 20th century.

Billy Graham (born November 7, 1918, Charlotte, North Carolina, U.S.—died February 21, 2018, Montreat, North Carolina), American evangelist whose large-scale preaching missions, known as crusades, and friendship with numerous U.S. presidents brought him to international prominence.

Conversion and early career

The son of a prosperous dairy farmer, Billy Graham grew up in rural North Carolina. In 1934, while attending a revival meeting led by the evangelist Mordecai Ham, he underwent a religious experience and professed his “decision for Christ.” In 1936 he left his father’s dairy farm to attend Bob Jones College (now Bob Jones University), then located in Cleveland, Tennessee, but stayed for only a semester because of the extreme fundamentalism of the institution. He transferred to Florida Bible Institute (now Trinity College), near Tampa, graduated in 1940, and was ordained a minister by the Southern Baptist Convention. Convinced that his education was deficient, however, Graham enrolled at Wheaton College in Illinois. While at Wheaton, he met and married (1943) Ruth Bell, daughter of L. Nelson Bell, a missionary to China.

By the time Graham graduated from Wheaton in 1943, he had developed the preaching style for which he would become famous—a simple, direct message of sin and salvation that he delivered energetically and without condescension. “Sincerity,” he observed many years later, “is the biggest part of selling anything, including the Christian plan of salvation.” After a brief and undistinguished stint as pastor of Western Springs Baptist Church in the western suburbs of Chicago, Graham decided to become an itinerant evangelist. He joined the staff of a new organization called Youth for Christ in 1945 and in 1947 served as president of Northwestern Bible College in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Evangelism

Graham’s emergence as an evangelist came at a propitious moment for 20th-century Protestants. Protestantism in the United States was deeply divided as a result of controversies in the 1920s between fundamentalism and modernism (a movement that applied scholarly methods of textual and historical criticism to the study of the Bible). The public image of fundamentalists was damaged by the Scopes Trial of 1925, which concerned the teaching of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution in public schools in Tennessee; in his writings about the trial, the journalist and social critic H.L. Mencken successfully portrayed all fundamentalists as uneducated country bumpkins. In response to these controversies, most fundamentalists withdrew from the established Protestant denominations, which they regarded as hopelessly liberal, and retreated from the larger society, which they viewed as both corrupt and corrupting. Although Graham remained theologically conservative, he refused to be sectarian like other fundamentalists. Seeking to dissociate himself from the image of the stodgy fundamentalist preacher, he seized on the opportunity presented by new media technologies, especially radio and television, to spread the message of the gospel.

In the late 1940s Graham’s fellow evangelist in Youth for Christ, Charles Templeton, challenged Graham to attend seminary with him so that both preachers could shore up their theological knowledge. Graham considered the possibility at length, but in 1949, while on a spiritual retreat in the San Bernardino Mountains of southern California, he decided to set aside his intellectual doubts about Christianity and simply “preach the gospel.” After his retreat, Graham began preaching in Los Angeles, where his crusade brought him national attention. He acquired this new fame in no small measure because newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, impressed with the young evangelist’s preaching and anticommunist rhetoric, instructed his papers to “puff Graham.” The huge circus tent in which Graham preached, as well as his own self-promotion, lured thousands of curious visitors—including Hollywood movie stars and gangsters—to what the press dubbed the “canvas cathedral” at the corner of Washington and Hill streets. From Los Angeles, Graham undertook evangelistic crusades around the country and the world, eventually earning international renown.

Despite his successes, Graham faced criticism from both liberals and conservatives. In New York City in 1954 he was received warmly by students at Union Theological Seminary, a bastion of liberal Protestantism; nevertheless, the theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, a professor at Union and one of the leading Protestant thinkers of the 20th century, had little patience for Graham’s simplistic preaching. On the other end of the theological spectrum, fundamentalists such as Bob Jones, Jr., Carl McIntire, and Jack Wyrtzen never forgave Graham for cooperating with the Ministerial Alliance, which included mainline Protestant clergy, in the planning and execution of Graham’s storied 16-week crusade at Madison Square Garden in New York in 1957. Such cooperation, however, was part of Graham’s deliberate strategy to distance himself from the starchy conservatism and separatism of American fundamentalists. His entire career, in fact, was marked by an irenic spirit.

Graham, by his own account, enjoyed close relationships with several American presidents, from Dwight Eisenhower to George W. Bush. (Although Graham met with Harry Truman in the Oval Office, the president was not impressed with him.) Despite claiming to be apolitical, Graham became politically close to Richard Nixon, whom he had befriended when Nixon was Eisenhower’s vice president. During the 1960 presidential campaign, in which Nixon was the Republican nominee, Graham met in Montreaux, Switzerland, with Norman Vincent Peale and other Protestant leaders to devise a strategy to derail the campaign of John F. Kennedy, the Democratic nominee, in order to secure Nixon’s election and prevent a Roman Catholic from becoming president. Although Graham later mended relations with Kennedy, Nixon remained his favourite politician; indeed, Graham all but endorsed Nixon’s reelection effort in 1972 against George McGovern. As Nixon’s presidency unraveled amid charges of criminal misconduct in the Watergate scandal, Graham reviewed transcripts of Oval Office tape recordings subpoenaed by Watergate investigators and professed to be physically sickened by his friend’s use of foul language.

Legacy of Billy Graham

Graham’s popular appeal was the result of his extraordinary charisma, his forceful preaching, and his simple, homespun message: anyone who repents of sins and accepts Jesus Christ will be saved. Behind that message, however, stood a sophisticated organization, the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, incorporated in 1950, which performed extensive advance work in the form of favourable media coverage, cooperation with political leaders, and coordination with local churches and provided a follow-up program for new converts. The organization also distributed a radio program, Hour of Decision, a syndicated newspaper column, “My Answer,” and a magazine, Decision. Although Graham pioneered the use of television for religious purposes, he always shied away from the label “televangelist.” During the 1980s, when other television preachers were embroiled in sensational scandals, Graham remained above the fray, and throughout a career that spanned more than half a century few people questioned his integrity. In 1996 Graham and his wife received the Congressional Gold Medal of Honor, the highest civilian award bestowed by the United States, and in 2001 he was made an Honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (KBE). Graham concluded his public career with a crusade in Queens, New York, in June 2005.

Graham claimed to have preached in person to more people than anyone else in history, an assertion that few would challenge. His evangelical crusades around the world, his television appearances and radio broadcasts, his friendships with presidents, and his unofficial role as spokesman for America’s evangelicals made him one of the most recognized religious figures of the 20th century.