Others like spiritual hunger and other sermons Features >>

The Spirit Within & The Spirit Upon

In The School Of Christ - Lessons On Holiness In John 13–17

Holiness, Truth And The Presence Of God

.mobi-160.webp)

The 3 Most Important Things In Your Life

Getting Anger Under Control

Spiritual Authority

-160.webp)

Spiritual Direction (Wisdom For The Long Walk Of Faith)

The Torch And The Sword

Spirit-Controlled Temperament

Suffering And The Sovereignty Of God

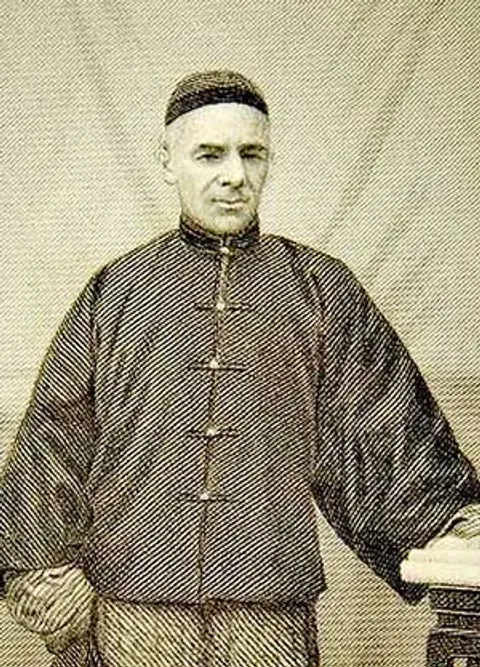

About the Book

"Spiritual Hunger and Other Sermons" by John G Lake is a collection of powerful sermons that address the spiritual hunger experienced by believers and challenges them to seek a deeper relationship with God. Lake's messages emphasize the importance of faith, prayer, and spiritual growth in order to experience God's power and blessings in their lives.

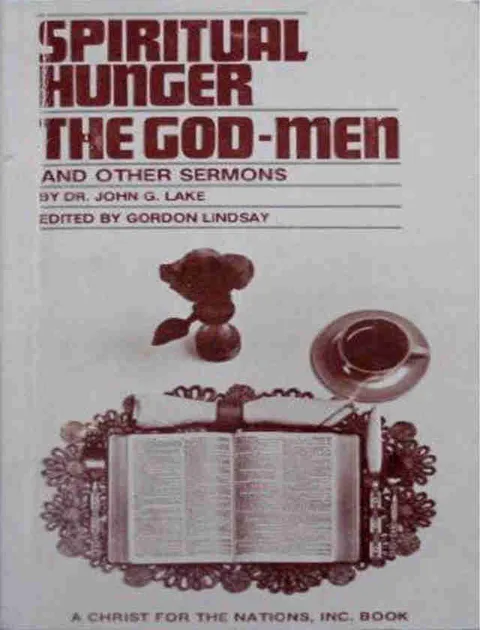

William Chalmers Burns

William Chalmers Burns was born in the Manse of Dun, in Angus, on April Ist, 1815. He was the third son of the Parish Church minister there. After leaving school, he went to Edinburgh to be apprenticed with an uncle to the legal profession. His eldest sister, a gay young lady, was converted to God, and became a bright witness for the Lord Jesus in 1831, and it was by means of her decided testimony that William was first awakened to a sense of his need of salvation, and led to put his trust in the Son of God, as his Redeemer and Saviour.

It was shortly after his conversion that he walked into the manse of Kilsyth, where the family then resided, having walked on foot the thirty-six miles from Edinburgh, to tell his mother and his sisters the glad news of his conversion, and to say that his desire now was to relinquish his study of law, and devote himself entirely to the preaching of the Gospel of God’s grace to his fellowmen.

And this he did heartily and with all his might, first in the neglected Parts of Scotland, and latterly among many heathen millions of the great Chinese Empire, then scarcely touched by the feet of God’s messengers of peace.

Mr. Burns’s name came into prominence in connection with a wonderful work of grace in Dundee, while he was preaching for Robert Murray M’Cheyne, then on a visit to Palestine, for the evangelization of the Jews. During Mr. Burns’s preaching in Dundee, a remarkable awakening took place; thousands were aroused to their condition in the sight of God, truly converted, and set on the heavenward way.

Remarkable scenes were witnessed in the old church of St. Peter’s, near to which M’Cheyne’s body now lies, awaiting the first resurrection. It was on the evening of a Lord’s Day in Kilsyth, after preaching to a crowded congregation, that Mr. Burns felt constrained to intimate to the people that he would preach to the people in the open air, before returning to Dundee the following day.

Deeply burdened with the souls of the people, he went into the village and invited the people, who thronged into the old church, until every seat and passage was filled. And the Lord helped His servant to preach straight to the people with great power, with the result that the whole congregation became melted under the message, many weeping aloud and crying to God for mercy. A glorious work of conversion followed.

Meetings for prayer and preaching of the Gospel continued in the churchyard, the market-place and elsewhere for weeks, while Mr. Burns returned to Dundee to resume his ministry. The work progressed in Dundee with increased interest, until the return of Mr. M’Cheyne, who greatly rejoiced in all that the Lord had done during his absence, through the ministry of His servant.

There was no jealousy, but the deepest gratitude, and these two true ministers of Christ rejoiced together over the Lord’s doings, which were indeed marvellous in their eyes.

From that time onward, until the Lord’s call came to go to China, Mr. Burns gave himself almost wholly to itinerant Gospel preaching, through Perthshire, up as far north as Aberdeen, preaching in barns, on market-places, and wherever the people could be gathered together to hear the Word. His message was plain, and to the point; thousands were awakened and many saved. But the adversary opposed. Time and again Mr. Burns was stoned, and bore the marks of these brands of the enemy for many days.

Believing it to be the call of the Lord, he went forth to China as the first missionary of the Presbyterian Church of England, in June, 1847. When questioned by those interested in his out-going, how long it would take him to prepare for the voyage, he replied with all simplicity, “I will be ready to go to-morrow.”

On a brief visit to his home, to take farewell of his sister, he silently wrung her hand, took a last glance around their old home, and with a small bag in his hand and his mother’s plaid across his arm, went forth, in the Name of the Lord with the Gospel to China’s benighted people, of whom it was said “a million a month” were dying without having once heard the Gospel.

For years this solitary witness toiled alone, at times with a few helpers, in the great heathen land, amid overwhelming hindrances, but his faith in God never faltered. On and on he went, sowing the seed which others would reap, until he reached the borders of the great kingdom of Manchuria, where, in a small, comfortless room in Nieu-chang, wearied and worn in labours abundant, he fell asleep on April 4th, 1868, his last audible words being, “For Thine is the Kingdom and the Power and the Glory.”

It is of this great land that the story of grace related in the following pages is told, and those who saw and shared in its joyful results, say that it was no doubt part of the result of William Burns’s sowing, in his earlier years in China.

William Chalmers Burns was born in the Manse of Dun, in Angus, on April Ist, 1815. He was the third son of the Parish Church minister there. After leaving school, he went to Edinburgh to be apprenticed with an uncle to the legal profession. His eldest sister, a gay young lady, was converted to God, and became a bright witness for the Lord Jesus in 1831, and it was by means of her decided testimony that William was first awakened to a sense of his need of salvation, and led to put his trust in the Son of God, as his Redeemer and Saviour.

It was shortly after his conversion that he walked into the manse of Kilsyth, where the family then resided, having walked on foot the thirty-six miles from Edinburgh, to tell his mother and his sisters the glad news of his conversion, and to say that his desire now was to relinquish his study of law, and devote himself entirely to the preaching of the Gospel of God’s grace to his fellowmen.

And this he did heartily and with all his might, first in the neglected Parts of Scotland, and latterly among many heathen millions of the great Chinese Empire, then scarcely touched by the feet of God’s messengers of peace.

Mr. Burns’s name came into prominence in connection with a wonderful work of grace in Dundee, while he was preaching for Robert Murray M’Cheyne, then on a visit to Palestine, for the evangelization of the Jews. During Mr. Burns’s preaching in Dundee, a remarkable awakening took place; thousands were aroused to their condition in the sight of God, truly converted, and set on the heavenward way.

Remarkable scenes were witnessed in the old church of St. Peter’s, near to which M’Cheyne’s body now lies, awaiting the first resurrection. It was on the evening of a Lord’s Day in Kilsyth, after preaching to a crowded congregation, that Mr. Burns felt constrained to intimate to the people that he would preach to the people in the open air, before returning to Dundee the following day.

Deeply burdened with the souls of the people, he went into the village and invited the people, who thronged into the old church, until every seat and passage was filled. And the Lord helped His servant to preach straight to the people with great power, with the result that the whole congregation became melted under the message, many weeping aloud and crying to God for mercy. A glorious work of conversion followed.

Meetings for prayer and preaching of the Gospel continued in the churchyard, the market-place and elsewhere for weeks, while Mr. Burns returned to Dundee to resume his ministry. The work progressed in Dundee with increased interest, until the return of Mr. M’Cheyne, who greatly rejoiced in all that the Lord had done during his absence, through the ministry of His servant.

There was no jealousy, but the deepest gratitude, and these two true ministers of Christ rejoiced together over the Lord’s doings, which were indeed marvellous in their eyes.

From that time onward, until the Lord’s call came to go to China, Mr. Burns gave himself almost wholly to itinerant Gospel preaching, through Perthshire, up as far north as Aberdeen, preaching in barns, on market-places, and wherever the people could be gathered together to hear the Word. His message was plain, and to the point; thousands were awakened and many saved. But the adversary opposed. Time and again Mr. Burns was stoned, and bore the marks of these brands of the enemy for many days.

Believing it to be the call of the Lord, he went forth to China as the first missionary of the Presbyterian Church of England, in June, 1847. When questioned by those interested in his out-going, how long it would take him to prepare for the voyage, he replied with all simplicity, “I will be ready to go to-morrow.”

On a brief visit to his home, to take farewell of his sister, he silently wrung her hand, took a last glance around their old home, and with a small bag in his hand and his mother’s plaid across his arm, went forth, in the Name of the Lord with the Gospel to China’s benighted people, of whom it was said “a million a month” were dying without having once heard the Gospel.

For years this solitary witness toiled alone, at times with a few helpers, in the great heathen land, amid overwhelming hindrances, but his faith in God never faltered. On and on he went, sowing the seed which others would reap, until he reached the borders of the great kingdom of Manchuria, where, in a small, comfortless room in Nieu-chang, wearied and worn in labours abundant, he fell asleep on April 4th, 1868, his last audible words being, “For Thine is the Kingdom and the Power and the Glory.”

It is of this great land that the story of grace related in the following pages is told, and those who saw and shared in its joyful results, say that it was no doubt part of the result of William Burns’s sowing, in his earlier years in China.

The Harvest of Homemaking

I have been a homemaker for over eighteen years now, and I feel confident saying it is a difficult and demanding job. What is more, it is a job with a massive PR problem. “It’s a soul-crushing grind!” some say. Others ask, “Do you work?” Public opinion on the nature of homemaking has not been subtle. For a generation at least, homemaking has been spoken of as a prison-like existence that stifles a woman’s gifts — as though homemakers have less ambition than others, less ability, less scope, less understanding. This propaganda effort has been radically effective, shaping the imagination of many women who find themselves at home for one reason or another. It takes little effort to see our calling and the work therein through the lens of resentment. Lately, there has been some pushback to the public opinion that homemaking is a life of boredom and ease, but it has been of the worst kind: long-faced social-media posts bemoaning how no one appreciates your work; TikTok videos telling everyone that because your family failed to notice the work you did, you feel invalidated as a person. This too is the fruit of worldly propaganda — and it too will have devastating effects. Homes in the Great War Homemakers often find ourselves without support — not physical support, the absence of which is so loudly reflected on, but rather the spiritual support of understanding why this field of work is glorious, worthy, essential, God-honoring, and strategic. We need an understanding of the value of the home that is strong enough to endure the tumultuous cultural winds around us. We need to see clearly how we are serving God in and with our work. “The Christian home is an essential work of the Christian resistance.” The Christian home is an essential work of the Christian resistance. In any war, it is customary to target your enemy’s supply lines, manufacturing plants, and headquarters. In our spiritual war, the Christian home is all of those things. Why then would it surprise us that the enemy would like to see the home destroyed? Why are we surprised by the obstacles we face — by the threefold resistance of the world, the flesh, and the devil? We have been cleverly fooled into thinking that the obstacles we face at home are due to the work being unimportant, insignificant, unappreciated, or mindless. We should have noticed that anything under such attack from both without and within must be desperately important. Beautiful or Embarrassing? You shall eat the fruit of the labor of your hands; you shall be blessed, and it shall be well with you. Your wife will be like a fruitful vine within your house, Your children will be like olive shoots around your table. Behold, thus shall the man be blessed who fears the Lord. (Psalm 128:3–4) Scripture is the basis for my commitment to being a homemaker, and if I never saw any other reason to love it, never saw the fruit, never understood the importance of the role, that should still be enough. Paul lays out the importance of older women teaching younger women to be “self-controlled, pure, working at home, kind, and submissive to their own husbands, that the word of God may not be reviled” (Titus 2:5). And Proverbs 31 describes a glorious picture of the woman who is clothed in strength and dignity as she gives herself to the needs of her household. At this point, some readers may have rolled their eyes because I mentioned Titus 2 and Proverbs 31 in the same embarrassingly uncool paragraph. Why is that? Could it be because you have been trained to despise passages like these? Could it be that you have listened to countless people explaining them away? Could it be that you have taken in enough worldly propaganda that you feel free to look down on the tone of the word of God and those who embrace it? I am asking you to consider that perhaps you have been played. You have been had. You have welcomed the lies of the world into your home and given them authority in your life. To say, “Women, be self-controlled, pure homemakers who love your husbands and children” is to speak a biblical, God-fearing statement. I am asking you now to listen to your own heart’s response to that. Is your heart bridling? Is it angry? Are you ready to post angry comments on my ignorant or backward ways? Well, think about what you are doing — it’s not me you are despising, but the words of God. What does your response say about where your heart is? Harvest of Homemaking I say that raw obedience to God’s word is enough, and in a sense it should be. But it is far from all that we are given. When I read those sorrowful monologues about the mental load, about how much it all weighs on the poor woman, about how unfair it all is, about how husbands should be responsible for far more housekeeping, all I can see is that women are suffering from the horrible pairing of trying to do the Lord’s work with the attitude of those who hate him. There will be no joy of obedience there. There will be no fruit of free giving there. There will be no strength and laughter and dignity there, because there is a thick fog of accusation, discontent, and envy. “The end of all our small daily plantings may be a harvest of staggering beauty.” I have come to realize through the years that the countless tasks I do that no one notices still shape our home and the people in it. Every meal I lay on the table is a small picture of the feeding of the five thousand. My meager offering, broken in the hands of Jesus, will feed generations of children. This home — the flavors and the smells and the atmosphere of love — will by God’s grace shape people who will go on to be the mothers and fathers of thousands. Is there any other work I could be doing that would be this exponentially fruitful or influential? A hundred years from now, I hope there are people who do not know my name or remember me, but nevertheless carry about with them seeds of faithful living that were first planted in the soil of this home. Do you have the burden of a million duties on your mind? Ask the Lord to establish the work of your hands. He makes valuable all that is done in him, so ask him to do so with your messy duties. Rejoice in him as you offer yourself as a living sacrifice — a sacrifice that cooks and cleans and blows noses and folds clothes and lays a table and looks after the ways of your household. He is shaping something of great beauty and strength that is far beyond our own capacity to imagine. May God give us all eyes to see it, and hearts to imagine it. The end of all our small daily plantings may be a harvest of staggering beauty. Article by Rachel Jankovic

-480.webp)