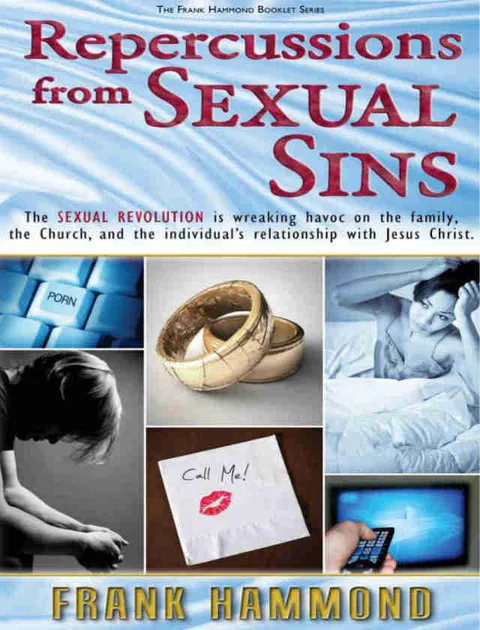

Others like repercussions from sexual sins Features >>

About the Book

"Repercussions from Sexual Sins" by Frank Hammond explores the spiritual and emotional consequences of engaging in sexual sin. The book offers insights and practical strategies for overcoming issues related to sexual immorality and finding healing and restoration. It delves into the damaging effects of sexual sin on individuals and relationships and provides guidance on how to break free from its destructive patterns.

Nik Ripken

Nik and Ruth, with 3 children, served for over 32 years obeying Christ’s command to share Jesus across the globe. After 7 years in Malawi & South Africa, they moved to Nairobi, Kenya to begin work among the Somali people (1991-1997). Since that time (1998-2013) they have journeyed globally among people whom, when they gave their lives to Jesus, faced increasing persecution for their faith.

The Ripkens and their teams served throughout the Horn of Africa within famine and war zones; resettling refugees, providing famine relief, and operating mobile medical clinics. Formerly Muslims, many Somali believers, suffered for their faith. Most were martyred. Near the end of the Ripken’s tenure among the Somalis, their 16-year-old son died of an asthma attack on Easter Sunday morning. He’s buried at the school from which the other Ripken children graduated.

One year later, the Holy Spirit led the Ripkens to begin a global pilgrimage to learn from believers in persecution how to recapture a biblical missiology of witness and house-church planting in the midst of persecution and martyrdom. Most of all, believers in persecution modeled for the Ripkens how to trust Jesus completely. Many of these lessons have been lost or forgotten by the church in the West.

Currently the Ripkens have interviewed over 600 believers in persecution, exceeding 72 countries. Sitting at their feet, the Ripkens learned from the suffering church how to thrive amidst suffering, not merely survive. The Ripkens, using everything they’ve learned from believers in persecution are creating resources as gifts from the church to the church. To date they have created articles, books, a music CD, a documentary, workshops, and other tools that allow the church in persecution to teach the church in the West about its biblical heritage of both crucifixion and resurrection. A teaching DVD is included in future plans. All these tools are designed to challenge believers to boldly follow Jesus, sharing their faith with others-no matter the cost.

Nik and Ruth, with 3 children, served for over 32 years obeying Christ’s command to share Jesus across the globe. After 7 years in Malawi & South Africa, they moved to Nairobi, Kenya to begin work among the Somali people (1991-1997). Since that time (1998-2013) they have journeyed globally among people whom, when they gave their lives to Jesus, faced increasing persecution for their faith.

The Ripkens and their teams served throughout the Horn of Africa within famine and war zones; resettling refugees, providing famine relief, and operating mobile medical clinics. Formerly Muslims, many Somali believers, suffered for their faith. Most were martyred. Near the end of the Ripken’s tenure among the Somalis, their 16-year-old son died of an asthma attack on Easter Sunday morning. He’s buried at the school from which the other Ripken children graduated.

One year later, the Holy Spirit led the Ripkens to begin a global pilgrimage to learn from believers in persecution how to recapture a biblical missiology of witness and house-church planting in the midst of persecution and martyrdom. Most of all, believers in persecution modeled for the Ripkens how to trust Jesus completely. Many of these lessons have been lost or forgotten by the church in the West.

Currently the Ripkens have interviewed over 600 believers in persecution, exceeding 72 countries. Sitting at their feet, the Ripkens learned from the suffering church how to thrive amidst suffering, not merely survive. The Ripkens, using everything they’ve learned from believers in persecution are creating resources as gifts from the church to the church. To date they have created articles, books, a music CD, a documentary, workshops, and other tools that allow the church in persecution to teach the church in the West about its biblical heritage of both crucifixion and resurrection. A teaching DVD is included in future plans. All these tools are designed to challenge believers to boldly follow Jesus, sharing their faith with others-no matter the cost.

‘One Another’ Your One and Only

What’s your favorite charge, or piece of counsel, you have heard in a wedding homily? Any Christian minister who has performed a wedding knows the challenge and opportunity of that moment. We have a precious few minutes to capture the moment and hang out a vision for the newlyweds to pursue for the rest of their days. On more than one occasion, I have surprised the couple with this charge: “Enjoy this day with everything you have, and when it is over, in one way, pretend like it never happened.” You can probably imagine their facial expressions. If it weren’t such a formal moment, I’m sure they would interrupt, “What do you mean, ‘Pretend like it never happened’? We’ve been waiting for this day for so long!” After a brief pause to allow their curiosity to grow, I go on to explain the wisdom behind my intentionally provocative words. The key to understanding the charge is in the phrase “in one way.” Kissing Pursuit Goodbye I am not charging couples to pretend like their wedding day never happened in every way, or even in most ways. Marriage brings many new and wonderful realities that are to be embraced with joyful seriousness. That said, I have observed that kissing the bride is often followed by kissing goodbye a way of loving each other. For so many, the wedding day marks the end of a way of relating that can be best characterized as the pursuit. While the specific practices may differ from one couple to another, the principle often remains the same: the dating days are characterized by a pursuit of the one we love, but as the months and years pass, the pursuit sadly gets left behind. It’s often replaced by a new “married” way of relating that could be characterized as existing together. This far-too-common pattern of relating can be summarized: Pursue. Catch. Exist. “Kissing the bride is often followed by kissing goodbye a way of loving each other.” While this dynamic of existing together often becomes the norm, what if there were another way? What if the transition from singleness to marriage should be and could be summarized differently? Consider this: Pursue. Catch. Pursue. I choose the phrases “should be” and “could be” because I am convinced that many spouses either lack a vision for why they should keep pursuing each other or they lack practical help in how to make it a reality (or both!). Why We Pursue Before rushing to discuss how we love one another, the Christian spouse would be well served to first clarify why. This question finds its answer in the way we are loved by God. God’s love for us establishes the bullseye for how we seek to love one another. We are called to love just as God loves us (John 13:15; Ephesians 4:32; 5:29). And this is clear: we are loved by a pursue-catch-pursue God. David captured God’s never-ending pursuit when he declared, “Surely goodness and mercy shall follow [or pursue] me all the days of my life, and I shall dwell in the house of the Lord forever” (Psalm 23:6). David rejoices in the reality that God’s pursuit wasn’t only to get him into his house, but it continues while he lives there. The apostle Paul gives an even longer view of the “hound of heaven” when he declares that for all eternity God will be showing “the immeasurable riches of his grace in kindness toward us in Christ Jesus” (Ephesians 2:7). Our God is ever in pursuit, and we are to follow his lead in the way we love — and first and foremost in the way we love our spouse. It’s worth clarifying that our goal is reflection, not perfection. None of us can perfectly love a spouse like Jesus does in all ways and at all times. While perfection is not the expectation, Spirit-filled followers of Christ should expect to consistently grow in our ability to reflect the love of God to our one and only. Consistent over Elaborate When I encourage couples to keep pursuing each other, I can already hear the objections, as if the idea is something out of a fairy tale, rather than one rooted in reality. “We can’t do that.” “We don’t have the time or the money for that.” “We have jobs, kids, responsibilities, and more often than not feel like we are being crushed each day.” “There’s just no way we can pursue one another like when we were dating and engaged.” These objections might be more valid if the call were to consistently pursue each other in elaborate ways. While elaborate pursuits have their place in a marriage, that’s not the first type of pursuit that couples should focus on. To put it in a phrase: consistent is greater than elaborate. Think about the love ethos of your marriage like building a fire. Before we add the large (elaborate) pieces of firewood, we first build a base of heat through placing many tiny sticks, twigs, and leaves. In fact, if we try to place a large piece of firewood too early, it will do the opposite of what we want. Instead of igniting the fire, it will put it out. The same is true in our marriages. When we neglect the small and consistent daily acts of pursuit, our elaborate attempts will often backfire. (Yes, I speak from personal experience.) The marriage that keeps the fire burning through each passing age and life stage is one in which both spouses commit to consistently, even daily, pursue one another. Little More Kindness Many spouses think too much about pursuing in elaborate ways and too little about consistent, everyday expressions of love. Our consumer-driven society leads us to focus on holidays and special days, when what our marriages often need most is a little more kindness and thoughtfulness each and every day. What if the missing piece in your marriage has little to do with figuring out how to love your spouse differently than everyone else? What if the secret to a better marriage is in learning to love your spouse just like you are called to love everyone else? I have often heard people say, “The Bible doesn’t give much guidance about marriage.” While the Bible may not speak exclusively about the relationship between husbands and wives as often as we’d like, it says a great deal about how we are to treat one another in Christ. God has given us dozens of specific “one another” commands in the mouth of Jesus and the letters of the apostles. He calls us to be kind to one another (Ephesians 4:32), serve one another (Galatians 5:13), forgive one another (Colossians 3:13), encourage one another (Hebrews 3:13), honor one another (Romans 12:10), live in harmony with one another (Romans 12:16), pray for one another (James 5:16), and submit to one another (Ephesians 5:21) — just to name a few. “Husbands and wives, you are called to ‘one another’ your ‘one and only.’” Husbands and wives, you are called to one-another your one-and-only. These small, seemingly simple expressions of intentional and authentic interest in your spouse, expressed consistently over time, can radically alter the culture of your marriage. First Steps Toward Each Other Sadly, many spouses seem content to take the “one another” commands out into the world during the day, but then leave them on the front porch as they walk into the home. How tragic would it be to have a Christian home with defined callings for husband and wife but without consistent and discernible Christlike love? God does not mean for a few explicit passages about marriage to replace all of God’s commands for how we treat one another. No, our one-and-only should be the first person we one-another. Our marriage love will be kindled by first committing to love our special one as we are called to love everyone. For many of us, this process begins with repentance. We have demanded to receive one-and-only love from our spouse, yet neglected to give one-another love to our spouse. If this is you, seek God’s help, ask your spouse to forgive you, and find a list of the “one another” commands in the New Testament. Read prayerfully over them and look for a few that the Holy Spirit presses on your heart to begin focusing on even this week. As you begin to one-another your one-and-only, you will be laying kindling and blowing oxygen on the fires of your marriage. Article by Matt Bradner

-160.webp)