Reposition Yourself: Living Life Without Limits Order Printed Copy

- Author: T. D. Jakes

- Size: 846KB | 251 pages

- |

Others like reposition yourself: living life without limits Features >>

About the Book

"Reposition Yourself: Living Life Without Limits" by T. D. Jakes is a motivational book that offers practical advice on how to take control of your life and achieve success by aligning your actions with your goals and values. Jakes encourages readers to let go of excuses, embrace change, and step into their full potential. Through personal anecdotes and concrete strategies, Jakes empowers readers to reposition themselves for greater fulfillment and success in all areas of life.

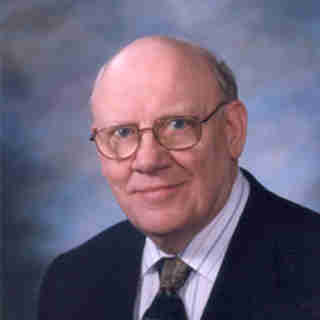

Warren Wiersbe

Dr. Warren Wiersbe once described Heaven as “not only a destination, but also a motivation. When you and I are truly motivated by the promise of eternity with God in heaven, it makes a difference in our lives.”

For Wiersbe, the promise of eternity became the motivation for his long ministry as a pastor, author, and radio speaker. Beloved for his biblical insight and practical teaching, he was called “one of the greatest Bible expositors of our generation” by the late Billy Graham.

Warren W. Wiersbe died on May 2, 2019, in Lincoln, Nebraska, just a few weeks shy of his 90th birthday.

“He was a longtime, cherished friend of Moody Bible Institute, a faithful servant of the Word, and a pastor to younger pastors like me,” said Dr. Mark Jobe, president of Moody Bible Institute. “We are lifting up pastor Wiersbe’s family in prayer at this time and rejoicing in the blessed hope that believers share together.”

Wiersbe grew up in East Chicago, Indiana, a town known for its steel mills and hard-working blue-collar families. In his autobiography, he connected some of his earliest childhood memories to Moody Bible Institute; his home church pastor was a 1937 graduate, Dr. William H. Taylor. After volunteering to usher at a 1945 Youth for Christ rally, Wiersbe found himself listening with rapt attention to Billy Graham’s sermon, and responded with a personal prayer of dedication.

In a precocious turn of events, the young Wiersbe was already a published author, having written a book of card tricks for the L. L. Ireland Magic Co. of Chicago. He quickly learned to liven up Sunday school lessons with magic tricks as object lessons (“not the cards!” he would say). After his high school graduation in 1947 (he was valedictorian), he spent a year at Indiana University before transferring to Northern Baptist Seminary in Chicago, where he earned a bachelor of theology degree. His future wife, Betty, worked in the school library, and Wiersbe was a frequent visitor.

While in seminary he became pastor of Central Baptist Church in East Chicago, serving until 1957. During those years he became a popular YFC speaker, which led to a full-time position with Youth for Christ International in Wheaton. He published his first article for Moody Monthly magazine in 1956, about Bible study methods, and seemed to outline his ongoing writing philosophy. “This is more of a personal testimony,” he said, “because I want to share these blessings with you, rather than write some scholarly essay, which I am sure I could not do anyway.”

At a 1957 YFC convention in Winona Lake, Indiana, Wiersbe preached a sermon that was broadcast live over WMBI, his first connection to Moody Radio. “I wish every preacher could have at least six months’ experience as a radio preacher,” he said later (because they would preach shorter).

While working with Youth for Christ, Wiersbe got a call from Pete Gunther at Moody Publishers, asking about possible book projects. First came Byways of Blessing (1961), an adult devotional; then two more books in 1962, A Guidebook for Teens and Teens Triumphant. He would eventually publish 14 titles with Moody, including William Culbertson: A Man of God (1974), Live Like a King (1976), The Annotated Pilgrim’s Progress (1980), and Ministering to the Mourning (2006), written with his son, David Wiersbe.

In 1961, D. B. Eastep invited Wiersbe to join the staff of Calvary Baptist Church in Covington, Kentucky. forming a succession plan that was hastened by Eastep’s sudden death in 1962. Warren and Betty Wiersbe remained at the church for 10 years, until they were surprised by a phone call from The Moody Church. The pastor, Dr. George Sweeting, had just resigned to become president of Moody Bible Institute. Would Wiersbe fill the pulpit, and pray about becoming a candidate?

He was already well known to the Chicago church—and to the MBI community. He continued to write for Moody Monthly and had just started a new column, “Insights for the Pastor.” The monthly feature continued to run during the years Wiersbe served at The Moody Church. Wiersbe would become one of the magazine’s most prolific writers—200 articles during a 40-year span. Meanwhile he also started work on the BE series of exegetical commentaries, books that soon found a place on the shelf of every evangelical pastor.

His ministry to pastors continued as he spoke at Moody Founder’s Week, Pastors’ Conference, and numerous campus events. He also inherited George Sweeting’s role as host of the popular Songs in the Night radio broadcast, produced by Moody Radio’s Bob Neff and distributed on Moody’s growing network of radio stations.

Later in life he would move to Lincoln, Nebraska, where he served as host of the Back to the Bible radio broadcast. He also taught courses on preaching at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School and Grand Rapids Baptist Seminary. He kept writing, eventually publishing more than 150 books and losing track of how many (“I can’t remember them all, and I didn’t save copies of everything,” he said.)

Throughout his ministry, Warren Wiersbe described himself as a bridge builder, a reference to his homiletical method of moving “from the world of the Bible to the world of today so that we could get to the other side of glory in Jesus.” As explained by his grandson, Dan Jacobson, “His preferred tools were words, his blueprints were the Scriptures, and his workspace was a self-assembled library.”

Several of Wiersbe’s extended family are Moody alums, including a son, David Wiersbe ’76; grandson Dan Jacobsen ’09 and his wife, Kristin (Shirk) Jacobsen ’09; and great-nephew Ryan Smith, a current student.

During his long ministry and writing career, Warren Wiersbe covered pretty much every topic, including the inevitability of death. These words from Ministering to the Mourning offer a fitting tribute to his own ministry:

We who are in Christ know that if He returns before our time comes to die, we shall be privileged to follow Him home. God’s people are always encouraged by that blessed hope. Yet we must still live each day soberly, realizing that we are mortal and that death may come to us at any time. We pray, “Teach us to number our days aright, that we may gain a heart of wisdom” (Psalm 90:12).

Dr. Warren Wiersbe once described Heaven as “not only a destination, but also a motivation. When you and I are truly motivated by the promise of eternity with God in heaven, it makes a difference in our lives.”

For Wiersbe, the promise of eternity became the motivation for his long ministry as a pastor, author, and radio speaker. Beloved for his biblical insight and practical teaching, he was called “one of the greatest Bible expositors of our generation” by the late Billy Graham.

Warren W. Wiersbe died on May 2, 2019, in Lincoln, Nebraska, just a few weeks shy of his 90th birthday.

“He was a longtime, cherished friend of Moody Bible Institute, a faithful servant of the Word, and a pastor to younger pastors like me,” said Dr. Mark Jobe, president of Moody Bible Institute. “We are lifting up pastor Wiersbe’s family in prayer at this time and rejoicing in the blessed hope that believers share together.”

Wiersbe grew up in East Chicago, Indiana, a town known for its steel mills and hard-working blue-collar families. In his autobiography, he connected some of his earliest childhood memories to Moody Bible Institute; his home church pastor was a 1937 graduate, Dr. William H. Taylor. After volunteering to usher at a 1945 Youth for Christ rally, Wiersbe found himself listening with rapt attention to Billy Graham’s sermon, and responded with a personal prayer of dedication.

In a precocious turn of events, the young Wiersbe was already a published author, having written a book of card tricks for the L. L. Ireland Magic Co. of Chicago. He quickly learned to liven up Sunday school lessons with magic tricks as object lessons (“not the cards!” he would say). After his high school graduation in 1947 (he was valedictorian), he spent a year at Indiana University before transferring to Northern Baptist Seminary in Chicago, where he earned a bachelor of theology degree. His future wife, Betty, worked in the school library, and Wiersbe was a frequent visitor.

While in seminary he became pastor of Central Baptist Church in East Chicago, serving until 1957. During those years he became a popular YFC speaker, which led to a full-time position with Youth for Christ International in Wheaton. He published his first article for Moody Monthly magazine in 1956, about Bible study methods, and seemed to outline his ongoing writing philosophy. “This is more of a personal testimony,” he said, “because I want to share these blessings with you, rather than write some scholarly essay, which I am sure I could not do anyway.”

At a 1957 YFC convention in Winona Lake, Indiana, Wiersbe preached a sermon that was broadcast live over WMBI, his first connection to Moody Radio. “I wish every preacher could have at least six months’ experience as a radio preacher,” he said later (because they would preach shorter).

While working with Youth for Christ, Wiersbe got a call from Pete Gunther at Moody Publishers, asking about possible book projects. First came Byways of Blessing (1961), an adult devotional; then two more books in 1962, A Guidebook for Teens and Teens Triumphant. He would eventually publish 14 titles with Moody, including William Culbertson: A Man of God (1974), Live Like a King (1976), The Annotated Pilgrim’s Progress (1980), and Ministering to the Mourning (2006), written with his son, David Wiersbe.

In 1961, D. B. Eastep invited Wiersbe to join the staff of Calvary Baptist Church in Covington, Kentucky. forming a succession plan that was hastened by Eastep’s sudden death in 1962. Warren and Betty Wiersbe remained at the church for 10 years, until they were surprised by a phone call from The Moody Church. The pastor, Dr. George Sweeting, had just resigned to become president of Moody Bible Institute. Would Wiersbe fill the pulpit, and pray about becoming a candidate?

He was already well known to the Chicago church—and to the MBI community. He continued to write for Moody Monthly and had just started a new column, “Insights for the Pastor.” The monthly feature continued to run during the years Wiersbe served at The Moody Church. Wiersbe would become one of the magazine’s most prolific writers—200 articles during a 40-year span. Meanwhile he also started work on the BE series of exegetical commentaries, books that soon found a place on the shelf of every evangelical pastor.

His ministry to pastors continued as he spoke at Moody Founder’s Week, Pastors’ Conference, and numerous campus events. He also inherited George Sweeting’s role as host of the popular Songs in the Night radio broadcast, produced by Moody Radio’s Bob Neff and distributed on Moody’s growing network of radio stations.

Later in life he would move to Lincoln, Nebraska, where he served as host of the Back to the Bible radio broadcast. He also taught courses on preaching at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School and Grand Rapids Baptist Seminary. He kept writing, eventually publishing more than 150 books and losing track of how many (“I can’t remember them all, and I didn’t save copies of everything,” he said.)

Throughout his ministry, Warren Wiersbe described himself as a bridge builder, a reference to his homiletical method of moving “from the world of the Bible to the world of today so that we could get to the other side of glory in Jesus.” As explained by his grandson, Dan Jacobson, “His preferred tools were words, his blueprints were the Scriptures, and his workspace was a self-assembled library.”

Several of Wiersbe’s extended family are Moody alums, including a son, David Wiersbe ’76; grandson Dan Jacobsen ’09 and his wife, Kristin (Shirk) Jacobsen ’09; and great-nephew Ryan Smith, a current student.

During his long ministry and writing career, Warren Wiersbe covered pretty much every topic, including the inevitability of death. These words from Ministering to the Mourning offer a fitting tribute to his own ministry:

We who are in Christ know that if He returns before our time comes to die, we shall be privileged to follow Him home. God’s people are always encouraged by that blessed hope. Yet we must still live each day soberly, realizing that we are mortal and that death may come to us at any time. We pray, “Teach us to number our days aright, that we may gain a heart of wisdom” (Psalm 90:12).

The Pursuit of True Discipleship

I learned as a very new Christian that if I was going to grow in the image of Christ I had to guard my heart. Here’s what that looked like for me. Very early on in my Christian walk, when I was almost 21 years old, I knew that I needed to be a woman of the Word. I began to guard my heart and my life by regularly engaging in the Bible. What’s important to know is that the most effective way to stay actively engaged in the Bible is not only to read the Word by yourself but also to read it with a small group. Everything you do personally is then maximized and multiplied when you’re in a group with a room full of women. The Holy Spirit is speaking to each and every one in the group as everyone is doing her daily reading throughout the week. The Lord has created each of us completely differently, unique from each other. So in a group we read the same passages every single week together, and yet the Lord speaks to us differently through every season of life we’re in. When we get to sit around the table or sit around someone’s living room and share exactly what we have each heard from the Lord, it’s a beautiful process that the Holy Spirit uses in our individual lives but also in the lives of all of those women who are meeting together. So this is a two-fold process. Not only do we grow personally, but we’re also growing as a unit — and that's a beautiful thing. I really hope you’re excited about what this might look like in your life. "Actively choose to put yourself in an atmosphere and environment to follow after Him, to constantly be changed into His image on this side of eternity." So, what is a disciple? I love to answer that question, because I think sometimes we make it more difficult than it actually is. Simply put, a disciple is a lifelong learner of Jesus Christ — someone who truly follows after Him all the days of her life. You actively choose to put yourself in an atmosphere and environment to follow after Him, to constantly be changed into His image on this side of eternity. Discipleship, then, means to intentionally equip believers with the Word of God, through accountable relationships and empowered by the Holy Spirit, in order to replicate faithful followers of Christ. Every single phrase in that definition is very important. One, it’s intentional. Two, we are equipping believers with the Word of God. From the beginning we must understand that the centerpiece of discipleship is God’s Word. Everything must always revolve around the centerpiece, because only God’s Word in the Spirit will change the hearts and the lives of people. We must intentionally equip believers with the Word of God. We’re doing that through accountable relationships and through the empowerment of the Holy Spirit. The end goal is always to replicate that process to make more disciples. John 8:31-32 says, “Then Jesus said to the Jews who had believed him, ‘If you continue in my word, you really are my disciples. You will know the truth, and the truth will set you free.’” I don't know about you, but I can always use more truth and freedom in my life — freedom from sin, freedom from bondage, and everything else that holds on to us in this world. We need to be women who say, I'm going to abide in Christ. I’m going to remain in His Word because remaining in His Word means that I am truly a disciple. Kandi Gallaty

-160.webp)

-480.webp)