Others like good to great Features >>

About the Book

"Good to Great" by Jim Collins explores why some companies make the leap from being good to becoming great, while others fail to do so. Collins and his research team analyzed data from 28 companies that achieved sustained greatness and identified key attributes that set them apart, such as level 5 leadership, a culture of discipline, and the concept of the hedgehog principle. The book provides valuable insights for leaders looking to take their organizations to the next level of success.

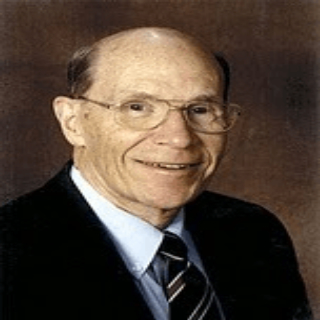

Jerry Bridges

Jerry Bridges entered into the joy of his Master on Sunday evening, March 6, 2016, at Penrose Hospital in Colorado Springs, the day after he suffered cardiac arrest. He was 86 years old.

Childhood

Gerald Dean Bridges was born on December 4, 1929, in a cotton-farming home in Tyler, Texas, to fundamentalist parents, six weeks after the Black Tuesday stock market crash that led to the Great Depression.

Jerry was born with several disabilities: he was cross-eyed, he was deaf in his right ear (which was not fully developed), and he had spine and breastbone deformities. But given his family’s poverty, they were unable to afford medical care for these challenges.

The separatist church in East Texas where the Bridges were members had an altar call after every service. Jerry walked the aisle three times, at the ages of 9, 11, and 13. But he later realized that he had not been born again.

His mother Lillian passed away in 1944 when he was 14.

Conversion

In August of 1948, as an 18-year-old college student right before his sophomore year began, Jerry was home alone one night in bed. He acknowledged to the Lord that he was not truly a Christian, despite growing up in a Christian home and professing faith. He prayed, ”God whatever it takes, I want Christ to be my Savior.”

The next week in his dorm room at the University of Oklahoma he was working on a school assignment and reached for a textbook, when he noticed the little Bible his parents had given him in high school. He figured that since he was now a Christian, he ought to start reading it daily, which he did (and never stopped doing for the rest of his days).

The Navy

After graduating with an engineering degree on a Navy ROTC scholarship, he went on active duty with the Navy, serving as an officer during the Korean conflict (1951-1953). A fellow officer invited him to go to a Navigator Bible study. Jerry went and he was hooked. He had never experienced anything like this before.

When stationed on ship in Japan, he got to know several staff members of the Navigators quite well. One day, after Jerry had been in Japan for six months, a Navy worker asked him why he didn’t just throw in his lot with the Navigators and come to work for them. The very next day, December 26, 1952, Jerry failed a physical exam due to the hearing loss in his right ear, and he was given a medical discharge in July 1953, after being in the Navy for only two years. Jerry was not overly disappointed, surmising that perhaps this was the Lord’s way of steering him to the Navigators.

When he returned to the U.S., he began working for Convair, an airplane manufacturing company in southern California, writing technical papers for shop and flight line personnel. It was there that he learned to write simply and clearly—skills the Lord would later use to instruct and edify thousands of people from his pen.

The Navigators

Jerry was single at the time, living in the home of Navigator Glen Solum, a common practice in the early days of The Navigators. In 1955 Jim invited Jerry to go with him to a staff conference at the headquarters of The Navigators in Glen Eyrie at Colorado Springs. It was there that Jerry sensed a call from the Lord to be involved with vocational ministry. He was resistant to the idea of going on staff, but felt conviction and prayed to the Lord, “Whatever you want.” The following day he met Dawson Trotman, the 49-year-old founder of The Navigators, who wanted to interview Jerry for a position, which he received and accepted. Jerry was put in charge of the correspondence department—answering letters, handling receipts, and mainly the NavLog newsletter to supporters.

When Trotman died in June of 1956 (saving a girl who was drowning), Jim Downing took a position equivalent to a chief operations operator. A Navy man, Jim Downing knew that Jerry had also served in the Navy and tapped him to be his assistant.

Jerry struggled at times in his role, unsure if this was his calling since his position was so different from the typical campus reps. After ten years on staff he told the Lord, “I’m going to do this for the rest of my life. If you want me out of The Navigators you’ll have to let me know.”

Beginning in 1960, Jerry served for three years in Europe as administrative assistant to the Navigators’ Europe Director. In January of 1960, he read a booklet entitled The Doctrine of Election, which he first considered heresy but then embraced the following day.

In October of 1963, at the age of 34, he married his first wife, Eleanor Miller of The Navigators following a long-distance relationship. Two children followed: Kathy in 1966, and Dan in 1967. From 1965 to 1969 Jerry served as office manager for The Navigators’ headquarters office at Glen Eyrie.

From 1969 to 1979 Jerry served as the Secretary-Treasurer for The Navigators. It was during this time that NavPress was founded in 1975. Their first publications began by transcribing and editing audio material from their tape archives and turning them into booklets. They produced one by Jerry on Willpower. Leroy Eims—who started the Collegiate ministry—encouraged Jerry to try his hand at writing new material. Jerry had been teaching at conferences on holiness, so he suggested a book along those lines.

In 1978, NavPress published The Pursuit of Holiness, which has now sold over 1.5 million copies. Jerry assumed it would be his only book. A couple of years later, after reading about putting off the old self and putting on the new self from Ephesians 4, he decided to write The Practice of Godliness—on developing a Christlike character. That book went on to sell over half a million copies, and his 1988 book on Trusting God has sold nearly a million copies.

Jerry served as The Navigators’ Vice President for Corporate Affairs from 1979 to 1994. It was in this season of ministry that Eleanor developed non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. She went to be with the Lord on November 9, 1988, just three weeks after their 25th wedding anniversary. On November 24, 1989, Jerry married Jane Mallot, who had known the Bridges family since the early ’70s.

Jerry’s final position with The Navigator’s was in the area of staff development with the Collegiate Mission. He saw this ministry as developing people, rather than teaching people how to do ministry. In addition to his work with The Navigators, he also maintained an active writing and teaching ministry, traveling the world to instruct and equip pastors and missionaries and other workers through conferences, seminars, and retreats.

Lessons

In 2014, Jerry published a memoir of his life, tracing the providential hand of God through his own story: God Took Me by the Hand: A Story of God’s Unusual Providence (NavPress, 2014). He closes the work with seven spiritual lessons he learned in his six decades of the Christian life:

The Bible is meant to be applied to specific life situations.

All who trust in Christ as Savior are united to Him in a loving way just as the branches are united to the vine.

The pursuit of holiness and godly character is neither by self-effort nor simply letting Christ “live His life through you.”

The sudden understanding of the doctrine of election was a watershed event for me that significantly affected my entire Christian life.

The representative union of Christ and the believer means that all that Christ did in both His perfect obedience and His death for our sins is credited to us.

The gospel is not just for unbelievers in their coming to Christ.

We are dependent on the Holy Spirit to apply the life of Christ to our lives.

His last book, The Blessing of Humility: Walk within Your Calling, will be published this summer by NavPress.

Legacy

One of the great legacies of Jerry Bridges is that he combined—to borrow some titles from his books—the pursuit of holiness and godliness with an emphasis on transforming grace. He believed that trusting God not only involved believing what he had done for us in the past, but that the gospel empowers daily faith and is transformative for all of life.

In 2009 he explained to interviewer Becky Grosenbach the need for this emphasis within the culture of the ministry he had given his life to:

When I came on staff almost all the leaders had come out of the military and we had pretty much a military culture. We were pretty hard core. We were duty driven. The WWII generation. We believed in hard work. We were motivated by saying “this is what you ought to do.” That’s okay, but it doesn’t serve you over the long haul. And so 30 years ago there was the beginning of a change to emphasize transforming grace, a grace-motivated discipleship.

In the days ahead, many will write tributes of this dear saint (see, e.g., this one from his friend, prayer partner, and sometimes co-author Bob Bevington). I would not be able to improve upon the reflections and remembrances of those who knew him better than I did. But I do know that he received from the Lord the ultimate acclamation as he entered into the joy of his Master and received the words we all long to hear, “Well done, my good and faithful servant.” There was nothing flashy about Jerry Bridges. He was a humble and unassuming man—strong in spirit, if not in voice or frame. And now we can rejoice with him in his full and final healing as he beholds his beloved Savior face to face. Thank you, God, for this man who helped us see and know you more.

Jerry Bridges wrote more than 20 books over the course of nearly 40 years:

The Pursuit of Holiness (NavPress, 1978)

The Practice of Godliness (NavPress, 1983)

True Fellowship (NavPress, 1985) [later published as The Crisis of Caring (P&R, 1992); finally republished with a major revision as True Community (NavPress, 2012)]

Trusting God (NavPress, 1988)

Transforming Grace (NavPress, 1991)

The Discipline of Grace (NavPress, 1994)

The Joy of Fearing God (Waterbrook, 1997)

I Exalt You, O God (Waterbrook, 2000)

I Give You Glory, O God (Waterbrook, 2002)

The Gospel for Real Life (NavPress, 2002)

The Chase (NavPress, 2003) [taken from Pursuit of Holiness]

Growing Your Faith (NavPress, 2004)

Is God Really in Control? (NavPress, 2006)

The Fruitful Life (NavPress, 2006)

Respectable Sins (NavPress, 2007) [student edition, 2013]

The Great Exchange [co-authored with Bob Bevington] (Crossway, 2007)

Holiness Day by Day (NavPress, 2008) [a devotional drawing from his earlier writing on holiness]

The Bookends of the Christian Life [co-authored with Bob Bevington] (Crossway, 2009)

Who Am I? (Cruciform, 2012)

The Transforming Power of the Gospel (NavPress, 2012)

31 Days Toward Trusting God (NavPress, 2013) [abridged from Trusting God]

God Took Me by the Hand (NavPress, 2014)

The Blessing of Humility: Walk within Your Calling (NavPress, 2016)

For an audio library of Jerry Bridges’ talks, go here.

Funeral

Visitation for Jerry Bridges was held on Thursday, March 10, 2016, from 5 to 8 pm, at Shrine of Remembrance (1730 East Fountain Blvd, Colorado Springs, CO 80910).

The memorial service was held on Friday, March 11, 2016, at 2 pm at Village Seven Presbyterian Church (4055 Nonchalant Circle South, Colorado Springs, CO 80917).

Jerry Bridges entered into the joy of his Master on Sunday evening, March 6, 2016, at Penrose Hospital in Colorado Springs, the day after he suffered cardiac arrest. He was 86 years old.

Childhood

Gerald Dean Bridges was born on December 4, 1929, in a cotton-farming home in Tyler, Texas, to fundamentalist parents, six weeks after the Black Tuesday stock market crash that led to the Great Depression.

Jerry was born with several disabilities: he was cross-eyed, he was deaf in his right ear (which was not fully developed), and he had spine and breastbone deformities. But given his family’s poverty, they were unable to afford medical care for these challenges.

The separatist church in East Texas where the Bridges were members had an altar call after every service. Jerry walked the aisle three times, at the ages of 9, 11, and 13. But he later realized that he had not been born again.

His mother Lillian passed away in 1944 when he was 14.

Conversion

In August of 1948, as an 18-year-old college student right before his sophomore year began, Jerry was home alone one night in bed. He acknowledged to the Lord that he was not truly a Christian, despite growing up in a Christian home and professing faith. He prayed, ”God whatever it takes, I want Christ to be my Savior.”

The next week in his dorm room at the University of Oklahoma he was working on a school assignment and reached for a textbook, when he noticed the little Bible his parents had given him in high school. He figured that since he was now a Christian, he ought to start reading it daily, which he did (and never stopped doing for the rest of his days).

The Navy

After graduating with an engineering degree on a Navy ROTC scholarship, he went on active duty with the Navy, serving as an officer during the Korean conflict (1951-1953). A fellow officer invited him to go to a Navigator Bible study. Jerry went and he was hooked. He had never experienced anything like this before.

When stationed on ship in Japan, he got to know several staff members of the Navigators quite well. One day, after Jerry had been in Japan for six months, a Navy worker asked him why he didn’t just throw in his lot with the Navigators and come to work for them. The very next day, December 26, 1952, Jerry failed a physical exam due to the hearing loss in his right ear, and he was given a medical discharge in July 1953, after being in the Navy for only two years. Jerry was not overly disappointed, surmising that perhaps this was the Lord’s way of steering him to the Navigators.

When he returned to the U.S., he began working for Convair, an airplane manufacturing company in southern California, writing technical papers for shop and flight line personnel. It was there that he learned to write simply and clearly—skills the Lord would later use to instruct and edify thousands of people from his pen.

The Navigators

Jerry was single at the time, living in the home of Navigator Glen Solum, a common practice in the early days of The Navigators. In 1955 Jim invited Jerry to go with him to a staff conference at the headquarters of The Navigators in Glen Eyrie at Colorado Springs. It was there that Jerry sensed a call from the Lord to be involved with vocational ministry. He was resistant to the idea of going on staff, but felt conviction and prayed to the Lord, “Whatever you want.” The following day he met Dawson Trotman, the 49-year-old founder of The Navigators, who wanted to interview Jerry for a position, which he received and accepted. Jerry was put in charge of the correspondence department—answering letters, handling receipts, and mainly the NavLog newsletter to supporters.

When Trotman died in June of 1956 (saving a girl who was drowning), Jim Downing took a position equivalent to a chief operations operator. A Navy man, Jim Downing knew that Jerry had also served in the Navy and tapped him to be his assistant.

Jerry struggled at times in his role, unsure if this was his calling since his position was so different from the typical campus reps. After ten years on staff he told the Lord, “I’m going to do this for the rest of my life. If you want me out of The Navigators you’ll have to let me know.”

Beginning in 1960, Jerry served for three years in Europe as administrative assistant to the Navigators’ Europe Director. In January of 1960, he read a booklet entitled The Doctrine of Election, which he first considered heresy but then embraced the following day.

In October of 1963, at the age of 34, he married his first wife, Eleanor Miller of The Navigators following a long-distance relationship. Two children followed: Kathy in 1966, and Dan in 1967. From 1965 to 1969 Jerry served as office manager for The Navigators’ headquarters office at Glen Eyrie.

From 1969 to 1979 Jerry served as the Secretary-Treasurer for The Navigators. It was during this time that NavPress was founded in 1975. Their first publications began by transcribing and editing audio material from their tape archives and turning them into booklets. They produced one by Jerry on Willpower. Leroy Eims—who started the Collegiate ministry—encouraged Jerry to try his hand at writing new material. Jerry had been teaching at conferences on holiness, so he suggested a book along those lines.

In 1978, NavPress published The Pursuit of Holiness, which has now sold over 1.5 million copies. Jerry assumed it would be his only book. A couple of years later, after reading about putting off the old self and putting on the new self from Ephesians 4, he decided to write The Practice of Godliness—on developing a Christlike character. That book went on to sell over half a million copies, and his 1988 book on Trusting God has sold nearly a million copies.

Jerry served as The Navigators’ Vice President for Corporate Affairs from 1979 to 1994. It was in this season of ministry that Eleanor developed non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. She went to be with the Lord on November 9, 1988, just three weeks after their 25th wedding anniversary. On November 24, 1989, Jerry married Jane Mallot, who had known the Bridges family since the early ’70s.

Jerry’s final position with The Navigator’s was in the area of staff development with the Collegiate Mission. He saw this ministry as developing people, rather than teaching people how to do ministry. In addition to his work with The Navigators, he also maintained an active writing and teaching ministry, traveling the world to instruct and equip pastors and missionaries and other workers through conferences, seminars, and retreats.

Lessons

In 2014, Jerry published a memoir of his life, tracing the providential hand of God through his own story: God Took Me by the Hand: A Story of God’s Unusual Providence (NavPress, 2014). He closes the work with seven spiritual lessons he learned in his six decades of the Christian life:

The Bible is meant to be applied to specific life situations.

All who trust in Christ as Savior are united to Him in a loving way just as the branches are united to the vine.

The pursuit of holiness and godly character is neither by self-effort nor simply letting Christ “live His life through you.”

The sudden understanding of the doctrine of election was a watershed event for me that significantly affected my entire Christian life.

The representative union of Christ and the believer means that all that Christ did in both His perfect obedience and His death for our sins is credited to us.

The gospel is not just for unbelievers in their coming to Christ.

We are dependent on the Holy Spirit to apply the life of Christ to our lives.

His last book, The Blessing of Humility: Walk within Your Calling, will be published this summer by NavPress.

Legacy

One of the great legacies of Jerry Bridges is that he combined—to borrow some titles from his books—the pursuit of holiness and godliness with an emphasis on transforming grace. He believed that trusting God not only involved believing what he had done for us in the past, but that the gospel empowers daily faith and is transformative for all of life.

In 2009 he explained to interviewer Becky Grosenbach the need for this emphasis within the culture of the ministry he had given his life to:

When I came on staff almost all the leaders had come out of the military and we had pretty much a military culture. We were pretty hard core. We were duty driven. The WWII generation. We believed in hard work. We were motivated by saying “this is what you ought to do.” That’s okay, but it doesn’t serve you over the long haul. And so 30 years ago there was the beginning of a change to emphasize transforming grace, a grace-motivated discipleship.

In the days ahead, many will write tributes of this dear saint (see, e.g., this one from his friend, prayer partner, and sometimes co-author Bob Bevington). I would not be able to improve upon the reflections and remembrances of those who knew him better than I did. But I do know that he received from the Lord the ultimate acclamation as he entered into the joy of his Master and received the words we all long to hear, “Well done, my good and faithful servant.” There was nothing flashy about Jerry Bridges. He was a humble and unassuming man—strong in spirit, if not in voice or frame. And now we can rejoice with him in his full and final healing as he beholds his beloved Savior face to face. Thank you, God, for this man who helped us see and know you more.

Jerry Bridges wrote more than 20 books over the course of nearly 40 years:

The Pursuit of Holiness (NavPress, 1978)

The Practice of Godliness (NavPress, 1983)

True Fellowship (NavPress, 1985) [later published as The Crisis of Caring (P&R, 1992); finally republished with a major revision as True Community (NavPress, 2012)]

Trusting God (NavPress, 1988)

Transforming Grace (NavPress, 1991)

The Discipline of Grace (NavPress, 1994)

The Joy of Fearing God (Waterbrook, 1997)

I Exalt You, O God (Waterbrook, 2000)

I Give You Glory, O God (Waterbrook, 2002)

The Gospel for Real Life (NavPress, 2002)

The Chase (NavPress, 2003) [taken from Pursuit of Holiness]

Growing Your Faith (NavPress, 2004)

Is God Really in Control? (NavPress, 2006)

The Fruitful Life (NavPress, 2006)

Respectable Sins (NavPress, 2007) [student edition, 2013]

The Great Exchange [co-authored with Bob Bevington] (Crossway, 2007)

Holiness Day by Day (NavPress, 2008) [a devotional drawing from his earlier writing on holiness]

The Bookends of the Christian Life [co-authored with Bob Bevington] (Crossway, 2009)

Who Am I? (Cruciform, 2012)

The Transforming Power of the Gospel (NavPress, 2012)

31 Days Toward Trusting God (NavPress, 2013) [abridged from Trusting God]

God Took Me by the Hand (NavPress, 2014)

The Blessing of Humility: Walk within Your Calling (NavPress, 2016)

For an audio library of Jerry Bridges’ talks, go here.

Funeral

Visitation for Jerry Bridges was held on Thursday, March 10, 2016, from 5 to 8 pm, at Shrine of Remembrance (1730 East Fountain Blvd, Colorado Springs, CO 80910).

The memorial service was held on Friday, March 11, 2016, at 2 pm at Village Seven Presbyterian Church (4055 Nonchalant Circle South, Colorado Springs, CO 80917).

10 Times Denzel Washington was Candid about His Christian Faith

Throughout his career, actor Denzel Washington has been open about his faith. Most recently, Washington reportedly offered some Biblical-inspired wisdom to actor Will Smith after he slapped comedian Chris Rock at the 2022 Oscars. Here's a look at 10 times Washington has talked about faith and its impact on his life and career. Denzel Washington, Washington shares his supernatural experience coming to Christ 1. Oscars 2022 on Smith-Rock Incident "Denzel said to me a few minutes ago, he said, 'At your highest moment, be careful— that's when the devil comes for you,'" Smith said during the Oscars while accepting his award. Smith was referring to the commercial break when Washington approached Smith after Smith rushed on stage to slap Rock for joking about Smith's wife. Washington's statement to Smith refers to 1 Peter 5:8, which says, "Be alert and of sober mind. Your enemy the devil prowls around like a roaring lion looking for someone to devour." 2. Showtime's Desus & Mero Podcast 2022 on talent "One of the most important lessons in life that you should know is to remember to have an attitude of gratitude, of humility, understand where the gift comes from," Washington said. "It's not mine, it's been given to me by the grace of God." 3. New York Times 2021 Interview on spiritual warfare "This is spiritual warfare. So, I'm not looking at it from an earthly perspective," Washington told the New York Times. "If you don't have a spiritual anchor, you'll be easily blown by the wind, and you'll be led to depression. "The enemy is the inner me," Washington added. "The Bible says in the last days – I don't know if it's the last days, it's not my place to know – but it says we'll be lovers of ourselves. The number one photograph today is a selfie, 'Oh, me at the protest.' 'Me with the fire.' 'Follow me.' 'Listen to me.'" 4. 2021 "The Better Man Event" on the role of a man "The John Wayne formula is not quite a fit right now. But strength, leadership, power, authority, guidance, [and] patience are God's gift to us as men. We have to cherish that, not abuse it. "I hope that the words in my mouth and the meditation of my heart are pleasing in God's sight, but I'm human. I'm just like you," he said. 5. 2021 Religion News Service Interview on how his faith impacted his film, "Journal for Jordan" "The spirit of God is throughout the film. Charles is an angel. I'm a believer. Dana's a believer. So that was a part of every decision, hopefully, that I tried to make. I wanted to please God, and I wanted to please Charles, and I wanted to please Dana." "I am a member, also a member of the (Cultural Christian Center) out here in New York. I have more than one spiritual leader in my life. So there's different people I talk to, and I try to make sure I try to put God first in everything. I was reading something this morning in my meditation about selfishness and how the only way to true independence is complete dependence on the Almighty." 6. Instagram Live with Pastor A.R. Bernard of Christian Cultural Center on his salvation "I was filled with the Holy Ghost, and it scared me. I said, 'Wait a minute, I didn't want to go this deep, I want to party,'" Washington said of the time he gave his life to Christ. "I went to church with Robert Townsend, and when it came time to come down to the altar, I said, 'You know this time, I'm just going to go down there and give it up and see what happens. I went in the prayer room and gave it up and let go and experienced something I've never experienced in my life." 7. 2017 The Christian Post Interview on advice for millennials "I would say to your generation – find a way to work together because this is a very divisive, angry time you're living in, unfortunately, because we didn't grow up like that," he said. "I pray for your generation," he added. "What an opportunity you have! Don't be depressed by it because we have to go through this, we're here now. You can't put that thing back in the box." 8. 2017 Screen Actors Guild Awards "I'm a God-fearing man. I'm supposed to have faith, but I didn't have faith," he said, according to Faith Wire. "God bless you all, all you other actors." 9. 2015 Church of God in Christ's Charity Banquet "Through my work, I have spoken to millions of people. In 2015, I said I'm no longer just going to speak through my work. I'm going to make a conscious effort to get up and speak about what God has done for me." 10. 2007 Reader's Digest Interview on his faith "I read the Bible every day. I'm in my second pass-through now, in the Book of John. My pastor told me to start with the New Testament, so I did, maybe two years ago. Worked my way through it, then through the Old Testament. Now I'm back in the New Testament. It's better the second time around." Amanda Casanova ChristianHeadlines.com Contributor