Christians In An Age Of Wealth - A Biblical Theology Of Stewardship Order Printed Copy

- Author: Craig L. Blomberg

- Size: 2.88MB | 509 pages

- |

Others like christians in an age of wealth - a biblical theology of stewardship Features >>

About the Book

"Christians In An Age Of Wealth" by Craig L. Blomberg explores the biblical principles of stewardship in a world of materialism and wealth. The book emphasizes the importance of managing resources and possessions in a way that honors God and promotes justice and generosity. Blomberg challenges readers to examine their attitudes towards money and possessions, and offers practical guidance on how to live a life of stewardship and generosity as faithful followers of Christ.

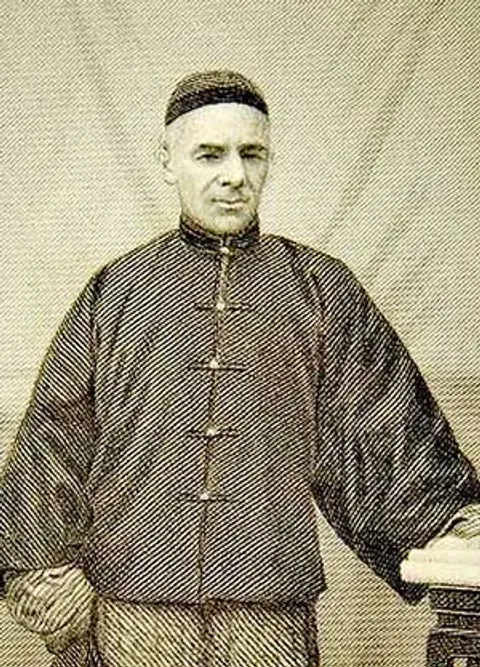

William Chalmers Burns

William Chalmers Burns was born in the Manse of Dun, in Angus, on April Ist, 1815. He was the third son of the Parish Church minister there. After leaving school, he went to Edinburgh to be apprenticed with an uncle to the legal profession. His eldest sister, a gay young lady, was converted to God, and became a bright witness for the Lord Jesus in 1831, and it was by means of her decided testimony that William was first awakened to a sense of his need of salvation, and led to put his trust in the Son of God, as his Redeemer and Saviour.

It was shortly after his conversion that he walked into the manse of Kilsyth, where the family then resided, having walked on foot the thirty-six miles from Edinburgh, to tell his mother and his sisters the glad news of his conversion, and to say that his desire now was to relinquish his study of law, and devote himself entirely to the preaching of the Gospel of God’s grace to his fellowmen.

And this he did heartily and with all his might, first in the neglected Parts of Scotland, and latterly among many heathen millions of the great Chinese Empire, then scarcely touched by the feet of God’s messengers of peace.

Mr. Burns’s name came into prominence in connection with a wonderful work of grace in Dundee, while he was preaching for Robert Murray M’Cheyne, then on a visit to Palestine, for the evangelization of the Jews. During Mr. Burns’s preaching in Dundee, a remarkable awakening took place; thousands were aroused to their condition in the sight of God, truly converted, and set on the heavenward way.

Remarkable scenes were witnessed in the old church of St. Peter’s, near to which M’Cheyne’s body now lies, awaiting the first resurrection. It was on the evening of a Lord’s Day in Kilsyth, after preaching to a crowded congregation, that Mr. Burns felt constrained to intimate to the people that he would preach to the people in the open air, before returning to Dundee the following day.

Deeply burdened with the souls of the people, he went into the village and invited the people, who thronged into the old church, until every seat and passage was filled. And the Lord helped His servant to preach straight to the people with great power, with the result that the whole congregation became melted under the message, many weeping aloud and crying to God for mercy. A glorious work of conversion followed.

Meetings for prayer and preaching of the Gospel continued in the churchyard, the market-place and elsewhere for weeks, while Mr. Burns returned to Dundee to resume his ministry. The work progressed in Dundee with increased interest, until the return of Mr. M’Cheyne, who greatly rejoiced in all that the Lord had done during his absence, through the ministry of His servant.

There was no jealousy, but the deepest gratitude, and these two true ministers of Christ rejoiced together over the Lord’s doings, which were indeed marvellous in their eyes.

From that time onward, until the Lord’s call came to go to China, Mr. Burns gave himself almost wholly to itinerant Gospel preaching, through Perthshire, up as far north as Aberdeen, preaching in barns, on market-places, and wherever the people could be gathered together to hear the Word. His message was plain, and to the point; thousands were awakened and many saved. But the adversary opposed. Time and again Mr. Burns was stoned, and bore the marks of these brands of the enemy for many days.

Believing it to be the call of the Lord, he went forth to China as the first missionary of the Presbyterian Church of England, in June, 1847. When questioned by those interested in his out-going, how long it would take him to prepare for the voyage, he replied with all simplicity, “I will be ready to go to-morrow.”

On a brief visit to his home, to take farewell of his sister, he silently wrung her hand, took a last glance around their old home, and with a small bag in his hand and his mother’s plaid across his arm, went forth, in the Name of the Lord with the Gospel to China’s benighted people, of whom it was said “a million a month” were dying without having once heard the Gospel.

For years this solitary witness toiled alone, at times with a few helpers, in the great heathen land, amid overwhelming hindrances, but his faith in God never faltered. On and on he went, sowing the seed which others would reap, until he reached the borders of the great kingdom of Manchuria, where, in a small, comfortless room in Nieu-chang, wearied and worn in labours abundant, he fell asleep on April 4th, 1868, his last audible words being, “For Thine is the Kingdom and the Power and the Glory.”

It is of this great land that the story of grace related in the following pages is told, and those who saw and shared in its joyful results, say that it was no doubt part of the result of William Burns’s sowing, in his earlier years in China.

William Chalmers Burns was born in the Manse of Dun, in Angus, on April Ist, 1815. He was the third son of the Parish Church minister there. After leaving school, he went to Edinburgh to be apprenticed with an uncle to the legal profession. His eldest sister, a gay young lady, was converted to God, and became a bright witness for the Lord Jesus in 1831, and it was by means of her decided testimony that William was first awakened to a sense of his need of salvation, and led to put his trust in the Son of God, as his Redeemer and Saviour.

It was shortly after his conversion that he walked into the manse of Kilsyth, where the family then resided, having walked on foot the thirty-six miles from Edinburgh, to tell his mother and his sisters the glad news of his conversion, and to say that his desire now was to relinquish his study of law, and devote himself entirely to the preaching of the Gospel of God’s grace to his fellowmen.

And this he did heartily and with all his might, first in the neglected Parts of Scotland, and latterly among many heathen millions of the great Chinese Empire, then scarcely touched by the feet of God’s messengers of peace.

Mr. Burns’s name came into prominence in connection with a wonderful work of grace in Dundee, while he was preaching for Robert Murray M’Cheyne, then on a visit to Palestine, for the evangelization of the Jews. During Mr. Burns’s preaching in Dundee, a remarkable awakening took place; thousands were aroused to their condition in the sight of God, truly converted, and set on the heavenward way.

Remarkable scenes were witnessed in the old church of St. Peter’s, near to which M’Cheyne’s body now lies, awaiting the first resurrection. It was on the evening of a Lord’s Day in Kilsyth, after preaching to a crowded congregation, that Mr. Burns felt constrained to intimate to the people that he would preach to the people in the open air, before returning to Dundee the following day.

Deeply burdened with the souls of the people, he went into the village and invited the people, who thronged into the old church, until every seat and passage was filled. And the Lord helped His servant to preach straight to the people with great power, with the result that the whole congregation became melted under the message, many weeping aloud and crying to God for mercy. A glorious work of conversion followed.

Meetings for prayer and preaching of the Gospel continued in the churchyard, the market-place and elsewhere for weeks, while Mr. Burns returned to Dundee to resume his ministry. The work progressed in Dundee with increased interest, until the return of Mr. M’Cheyne, who greatly rejoiced in all that the Lord had done during his absence, through the ministry of His servant.

There was no jealousy, but the deepest gratitude, and these two true ministers of Christ rejoiced together over the Lord’s doings, which were indeed marvellous in their eyes.

From that time onward, until the Lord’s call came to go to China, Mr. Burns gave himself almost wholly to itinerant Gospel preaching, through Perthshire, up as far north as Aberdeen, preaching in barns, on market-places, and wherever the people could be gathered together to hear the Word. His message was plain, and to the point; thousands were awakened and many saved. But the adversary opposed. Time and again Mr. Burns was stoned, and bore the marks of these brands of the enemy for many days.

Believing it to be the call of the Lord, he went forth to China as the first missionary of the Presbyterian Church of England, in June, 1847. When questioned by those interested in his out-going, how long it would take him to prepare for the voyage, he replied with all simplicity, “I will be ready to go to-morrow.”

On a brief visit to his home, to take farewell of his sister, he silently wrung her hand, took a last glance around their old home, and with a small bag in his hand and his mother’s plaid across his arm, went forth, in the Name of the Lord with the Gospel to China’s benighted people, of whom it was said “a million a month” were dying without having once heard the Gospel.

For years this solitary witness toiled alone, at times with a few helpers, in the great heathen land, amid overwhelming hindrances, but his faith in God never faltered. On and on he went, sowing the seed which others would reap, until he reached the borders of the great kingdom of Manchuria, where, in a small, comfortless room in Nieu-chang, wearied and worn in labours abundant, he fell asleep on April 4th, 1868, his last audible words being, “For Thine is the Kingdom and the Power and the Glory.”

It is of this great land that the story of grace related in the following pages is told, and those who saw and shared in its joyful results, say that it was no doubt part of the result of William Burns’s sowing, in his earlier years in China.

The Holiness from Below - A Warning Against Self-Righteousness

As he who called you is holy, you also be holy in all your conduct. (1 Peter 1:15) My hunch is that you are not a glib and shallow person. You are not the kind of person who would “pervert the grace of God into sensuality” (Jude 4). You are in earnest with the Lord, and you long to be holy. So do I. Indeed, what we deeply desire is nothing less than — may I come right out and say it? — sainthood. But Christians like us — who care so sincerely about holiness and are reaching so diligently for its high standards — we face our own temptation. Let’s come right out and say that too. If others pervert the grace of God, we can “nullify the grace of God” (Galatians 2:21). We can have “a zeal for God, but not according to knowledge” (Romans 10:2). We can “go beyond what is written . . . being puffed up in favor of one against another” (1 Corinthians 4:6). How could it be otherwise? There is always, in this life, more than one way to lose our way! Our very earnestness can become an opening to corruption, rot, and death. The great pastor and saint Robert Murray McCheyne warned his congregation, “Study sanctification to the utmost, but do not make a Christ of it. God hates this idol more than all others.” We should be serious about that too. So, let’s think about one way we can go so wrong, even while feeling we are so right. Two Kinds of Holiness Here is what we must understand. There are two kinds of holiness. One kind is Jesus’s holiness, and the other is our own self-invented holiness. Or to put it in other ways: There is the holiness of the Spirit, and there is the holiness of the flesh. There is the holiness from above, and the holiness from below. There is real holiness, and false holiness. “Real holiness from Jesus is, of course, like Jesus.” The difference is profound, even stark. But for us, it isn’t always easy to see the difference. Both kinds of holiness quote the Bible. Both talk about Jesus. Both go to church. Both are strict and firm and resolute. How then do these two holinesses differ? Real holiness from Jesus is, of course, like Jesus. Look carefully at what our key verse actually says: “As he who called you is holy, you also be holy in all your conduct” (1 Peter 1:15). His kind of holiness does not simply insist on a high moral standard. Any sinner can turn over a new leaf, and with enough willpower align externally with biblical norms. But real holiness reflects Jesus, it thinks like Jesus, its instincts resonate with Jesus. Real holiness embodies Jesus. Beauty of True Holiness When our Lord said, “Follow me” (Mark 1:17), he wasn’t recruiting our moral strengths to advance his cause. His call was and is, “I will teach you a new way of perceiving everything, including morality. I myself am how you avoid sin and become holy.” Jesus is why the Bible speaks of “the beauty of holiness” (Psalm 96:9, KJV). His holiness is humane, life-giving, and desirable in every worthy way. His holiness is both serious enough to warn and light enough to laugh (1 Peter 5:8; Zechariah 8:5); it’s firm and yet also freeing (Deuteronomy 5:32; Malachi 4:2). When we encounter our Lord’s real holiness in someone today, it’s both dignifying and delightful. But false holiness from us is, well, just us. It’s us at our worst, because it’s us exalting our smug superiority, us reinforcing our divisive preferences, us absolutizing our narrow rigidity, and so forth. It’s us asserting ourselves, in the name of the Lord, so that we become more demanding, more grim, more shaming of others. Great Divide I’ll make it still worse. Because false holiness comes so naturally to us, it feels good. Our moral fervor feels moral. But it isn’t. Our moral fervor is immoral. In those moments when we have enough self-awareness to see our carnal holiness for what it is, we are peering into a pit of hell. In Mere Christianity, C. S. Lewis teaches us, The sins of the flesh are bad, but they are the least bad of all sins. All the worst pleasures are purely spiritual: the pleasure of putting other people in the wrong, of bossing and patronizing and spoiling sport and back-biting; the pleasures of power, of hatred. For there are two things inside me, competing with the human self which I must try to become. They are the Animal self, and the Diabolical self. The Diabolical self is the worse of the two. That is why a cold, self-righteous prig who goes regularly to church may be far nearer to hell than a prostitute. But, of course, it is better to be neither. (102–103) If this is so, and it is, then our pursuit of holiness is complicated. We might have expected a choice between two simple categories: sin versus holiness. But in reality, we are facing three categories: (1) sin, (2) our kind of holiness, and, (3) Jesus’s kind of holiness. And the great divide is not between (1) and (2). The great divide is between (2) and (3). Heart of His Holiness If our holiness is no more than that — our wretched rightness — then our holiness is a polished form of evil. The Pharisees proved that. They were morally earnest people and the archvillains of the Gospels. “If our holiness is no more than our wretched rightness, then our holiness is a polished form of evil.” The Pharisees hated Jesus, even while many sinners gravitated to him. Why? Because his kind of holiness has no pride at all. He isn’t pushy and strident and harsh. He really is “gentle and lowly” (Matthew 11:29). And that part of him isn’t a concession, moderating his holiness. It’s at the very heart of his holiness, because it is the very heart of Jesus himself. His kind of holiness melts in the mouths of all who humble themselves before him. This distinction explains something that perplexed me for years. The most repulsive people I’ve encountered along the way are not the worldly party boys on their weekend binges; they are harsh “church people” with their high standards — and no forgiveness. But the loveliest people I’ve ever known have been sinners of many kinds who are turning from both their coarsened evil and their refined evil, and they are humbly opening up to Jesus and his grace for the undeserving. When I hang out with them, Jesus is present. Sometimes I am moved to tears. But among genuinely holy people, I do not feel cornered, pressured, or shamed by their negative scrutiny. The real saints are too holy for that arrogant foolishness. And I hope you have a ton of friends like that! Not Righteousness of My Own It isn’t just our blatant sins that need correction. Our counterfeit holiness needs correction too. It doesn’t need intensification. A. W. Tozer wrote of his generation, “A widespread revival of the kind of Christianity we know today in America might prove to be a moral tragedy from which we would not recover in a hundred years” (Keys to the Deeper Life, 18). I believe that applies even more today. What self-righteous holiness needs is not success, power, and prominence, but failure, collapse, and devastation. Then we can humbly receive Jesus, with the empty hands of faith, and enter into the profound experience Philippians 3:8–9 describes: For his sake I have suffered the loss of all things and count them as rubbish, in order that I may gain Christ and be found in him, not having a righteousness of my own that comes from the law, but that which comes through faith in Christ, the righteousness from God that depends on faith.