Others like the power to change the world Features >>

Holding To The Word Of The Lord

The Art Of Shepherding

-160.webp)

The Power Of Your Words: How God Can Bless Your Life Through The Words You Speak

How To Know The Will Of God

How To Live A Holy Life

The Overcoming Life

7 Things The Holy Spirit Will Do For You

Latent Power Of The Soul

How Can I Be Filled With The Holy Spirit

The Torch And The Sword

About the Book

"The Power To Change The World" by Rick Joyner explores the concept of spiritual transformation and the impact individuals have on the world around them when they align themselves with divine power. Joyner highlights the importance of personal responsibility, faith, and obedience in bringing positive change to society and encourages readers to discover their own unique abilities to make a difference in the world.

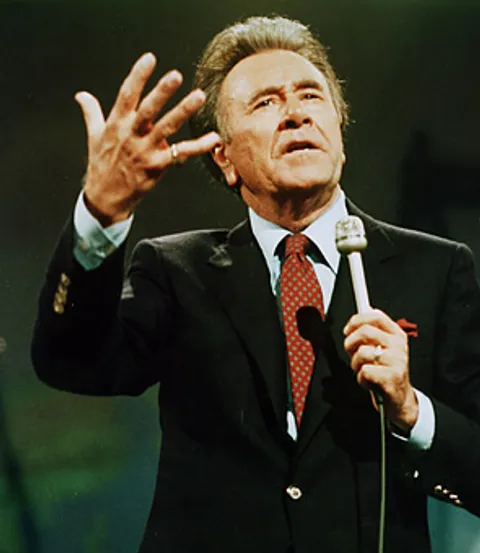

Oral Roberts

Granville Oral Roberts was born January 24, 1918 in Pontotoc County, near Ada, in Oklahoma. His parents were deeply religious. His father was a farmer who also preached the gospel and established Pentecostal Holiness churches. His mother regularly prayed for the sick and led people to Christ. While she was still pregnant, Robert's mother committed Oral to God's service. Even though Oral had a very strong stutter his mother would tell him that one day God would heal his tongue and he would speak to multitudes.

The Roberts family was desperately poor. When Roberts was 16 he moved away from home, hoping for a better life. He rejected God and his upbringing. He started living a wild life and his health collapsed. Roberts had contracted tuberculosis. He returned home and eventually dropped to 120 pounds. He was a walking skeleton. God spoke to his older sister, Jewel, and told her that He was going to heal Oral. During this same time Oral turned his heart back to God and gave his life to Christ. A traveling healing evangelist named George Moncey came to Ada and held meetings in a tent. Oral's elder brother was touched when he saw friends of his healed in the meeting. He decided that he should get Oral and bring him to be healed. On the way to the meeting God spoke to Oral and said "Son, I'm going to heal you and you are to take my healing power to your generation. You are to build me a University and build it on My authority and the Holy Spirit." Once at the meeting Oral waited until the very end. He was too sick to get up and receive prayer, and so had to wait for Moncey to come to him. At 11:00 at night his parents lifted him so he could stand. When Moncey prayed for him the power of God hit him and he was instantly healed. Not only that but every bit of his stutter was gone!

After Roberts was healed he began to travel the evangelistic circuit. He met and married Evelyn Lutman, a school teacher from the same Holiness Pentecostal background as Roberts. They had their first child Rebecca and then the entire family began traveling as ministers. In 1942 they left the evangelistic field for a while and Roberts became a pastor. He also returned to college to further his education. While a pastor he prayed for a church member whose foot was crushed. The foot was instantly healed. God continued to speak to Roberts about his call to the multitudes. God called him to an unusual fast. Roberts was to read the four gospels and the book of Acts three times consecutively, while on his knees, for thirty days. God began to reveal Jesus as the healer in a new way. God also began to give Roberts dreams where he would see people's needs as God saw them. God called him to hold a healing meeting in his town. A woman was dramatically healed, several people were saved and Roberts' ministry changed overnight.

Roberts resigned his church in 1947 and began an itinerant ministry. Notable healings began to occur. One man tried to shoot Roberts. God used the story to bring him media attention, which expanded his ministry very quickly. Roberts felt called to purchase a tent and take his evangelistic ministry to larger cities. His first tent held 3,000 but he quickly exchanged it for a tent that held 12,000. In July 1948 The Oral Roberts Evangelistic Association was established. Oral began traveling continuously throughout the United States. Like many of his Pentecostal brethren Roberts held inter-racial meetings. This brought him a lot of negative attention from groups who didn't like his stand. He even received death threats for not holding segregated meetings. In 1956 Roberts was invited to Australia. He held meetings in Sydney and Melbourne. In Melbourne there were outright physical attacks and destructive gangs. He was literally driven out of the city for praying for the sick. Often when people discuss the healing revival of the 1950s Oral Roberts and William Branham are listed as the most widely recognized leaders of the movement. Others came along side and many emulated them, but they were the most widely recognized personalities.

Roberts was a man who understood and used the media for his benefit. Roberts began publishing a magazine almost immediately upon starting his ministry. He grasped the power of radio and television. In 1954 Roberts began filming his crusades. He began playing his sermons on radio and then airing the crusade tapes during evening television prime time. Unfortunately there is some evidence that healing meetings were scripted ahead of time, and not all healings were genuine. People began writing to the Ministry headquarters by the thousands. They were accepting Christ as their savior after seeing a person healed on TV. By 1957 the ministry was receiving 1,000 letters a day and he was getting thousands of phone calls. He established a round the clock prayer team to answer calls and pray for people who contacted the ministry. In 1957 Roberts claimed 1,000,000 salvations. Between 1947 and 1968 Roberts conducted over 300 major Crusades. Money was flowing into the organization at an unprecedented rate.

In the late 1950s the healing movement was waning and ministries were under attack for their lack of financial accountability. Roberts began to move on the vision God gave him to build a University. It was chartered in 1963 and became open to students in 1965. Roberts was having a significant national impact in the late 1950s and early 1960s. For several years his named appeared in the Top 100 list of the nation's most respected people. Although Roberts continued to hold healing meetings his focus shifted to the University and the television programs.

The 1970s and 80s brought many crises to the Roberts family. Their daughter Rebecca and son-in-law Marshall were killed in a plane crash. Their son Ronnie struggled with depression after serving in Vietnam and also declaring himself gay. He grew despondent after losing his job and committed suicide. Richard Roberts got a divorce. After Richard remarried he and his wife lost a new born son within two days. Roberts began teaching a doctrine of "seed faith" where he claimed that if you gave to his ministry then God would pay you back in multiplied ways. The television ministry received heavy criticism for the constant requests for money. The Roberts were living an extravagance lifestyle while many of their supporters were not wealthy. Financial questions were raised in how Roberts used University endowment funds to purchase personal homes and cars.

In 1977 Roberts had a vision to build a hospital where people not only received care but received healing prayer. It was to be called City of Faith. Roberts put his heart and soul into the project, believing that God would build it as He had the University. The hospital struggled along and Roberts called his followers to give to the project, believing he had a vision from God to raise the money. Roberts even claimed twice that if money didn't come in that Jesus would "take him home." The hospital was built, but never succeeded financially, and finally closed in 1989. Financial giving was plummeting for both the Oral Roberts Evangelistic Association and Oral Roberts University.

Roberts retired in 1993, at the age of 75. Roberts, with his wife Evelyn, moved to California to live near the coast. Evelyn died in May 2005. Although Roberts influence waned after the problems of the 1970s and 1980s, he was still recognized for his pioneering work on the "sawdust trail", television evangelism, and building a Christian University. He often appeared on religious broadcasting networks as a recognized leader in the healing movement of the last half century. He died December 15, 2009 at the age of 91.

Oral Roberts' legacy is a mixed one. Roberts brought the truth of God's healing to the public in a way that few others accomplished in his lifetime. His financial and personal issues and increasingly extravagant claims eventually brought his ministry into disrepute. The University he established continued to have financial crises under the leadership of his son Richard Roberts. It was only after Richard stepped down in 2009 and new leadership took over the University that it stabilized financially. The University is no longer connected to the Oral Roberts Evangelistic Association.

Granville Oral Roberts was born January 24, 1918 in Pontotoc County, near Ada, in Oklahoma. His parents were deeply religious. His father was a farmer who also preached the gospel and established Pentecostal Holiness churches. His mother regularly prayed for the sick and led people to Christ. While she was still pregnant, Robert's mother committed Oral to God's service. Even though Oral had a very strong stutter his mother would tell him that one day God would heal his tongue and he would speak to multitudes.

The Roberts family was desperately poor. When Roberts was 16 he moved away from home, hoping for a better life. He rejected God and his upbringing. He started living a wild life and his health collapsed. Roberts had contracted tuberculosis. He returned home and eventually dropped to 120 pounds. He was a walking skeleton. God spoke to his older sister, Jewel, and told her that He was going to heal Oral. During this same time Oral turned his heart back to God and gave his life to Christ. A traveling healing evangelist named George Moncey came to Ada and held meetings in a tent. Oral's elder brother was touched when he saw friends of his healed in the meeting. He decided that he should get Oral and bring him to be healed. On the way to the meeting God spoke to Oral and said "Son, I'm going to heal you and you are to take my healing power to your generation. You are to build me a University and build it on My authority and the Holy Spirit." Once at the meeting Oral waited until the very end. He was too sick to get up and receive prayer, and so had to wait for Moncey to come to him. At 11:00 at night his parents lifted him so he could stand. When Moncey prayed for him the power of God hit him and he was instantly healed. Not only that but every bit of his stutter was gone!

After Roberts was healed he began to travel the evangelistic circuit. He met and married Evelyn Lutman, a school teacher from the same Holiness Pentecostal background as Roberts. They had their first child Rebecca and then the entire family began traveling as ministers. In 1942 they left the evangelistic field for a while and Roberts became a pastor. He also returned to college to further his education. While a pastor he prayed for a church member whose foot was crushed. The foot was instantly healed. God continued to speak to Roberts about his call to the multitudes. God called him to an unusual fast. Roberts was to read the four gospels and the book of Acts three times consecutively, while on his knees, for thirty days. God began to reveal Jesus as the healer in a new way. God also began to give Roberts dreams where he would see people's needs as God saw them. God called him to hold a healing meeting in his town. A woman was dramatically healed, several people were saved and Roberts' ministry changed overnight.

Roberts resigned his church in 1947 and began an itinerant ministry. Notable healings began to occur. One man tried to shoot Roberts. God used the story to bring him media attention, which expanded his ministry very quickly. Roberts felt called to purchase a tent and take his evangelistic ministry to larger cities. His first tent held 3,000 but he quickly exchanged it for a tent that held 12,000. In July 1948 The Oral Roberts Evangelistic Association was established. Oral began traveling continuously throughout the United States. Like many of his Pentecostal brethren Roberts held inter-racial meetings. This brought him a lot of negative attention from groups who didn't like his stand. He even received death threats for not holding segregated meetings. In 1956 Roberts was invited to Australia. He held meetings in Sydney and Melbourne. In Melbourne there were outright physical attacks and destructive gangs. He was literally driven out of the city for praying for the sick. Often when people discuss the healing revival of the 1950s Oral Roberts and William Branham are listed as the most widely recognized leaders of the movement. Others came along side and many emulated them, but they were the most widely recognized personalities.

Roberts was a man who understood and used the media for his benefit. Roberts began publishing a magazine almost immediately upon starting his ministry. He grasped the power of radio and television. In 1954 Roberts began filming his crusades. He began playing his sermons on radio and then airing the crusade tapes during evening television prime time. Unfortunately there is some evidence that healing meetings were scripted ahead of time, and not all healings were genuine. People began writing to the Ministry headquarters by the thousands. They were accepting Christ as their savior after seeing a person healed on TV. By 1957 the ministry was receiving 1,000 letters a day and he was getting thousands of phone calls. He established a round the clock prayer team to answer calls and pray for people who contacted the ministry. In 1957 Roberts claimed 1,000,000 salvations. Between 1947 and 1968 Roberts conducted over 300 major Crusades. Money was flowing into the organization at an unprecedented rate.

In the late 1950s the healing movement was waning and ministries were under attack for their lack of financial accountability. Roberts began to move on the vision God gave him to build a University. It was chartered in 1963 and became open to students in 1965. Roberts was having a significant national impact in the late 1950s and early 1960s. For several years his named appeared in the Top 100 list of the nation's most respected people. Although Roberts continued to hold healing meetings his focus shifted to the University and the television programs.

The 1970s and 80s brought many crises to the Roberts family. Their daughter Rebecca and son-in-law Marshall were killed in a plane crash. Their son Ronnie struggled with depression after serving in Vietnam and also declaring himself gay. He grew despondent after losing his job and committed suicide. Richard Roberts got a divorce. After Richard remarried he and his wife lost a new born son within two days. Roberts began teaching a doctrine of "seed faith" where he claimed that if you gave to his ministry then God would pay you back in multiplied ways. The television ministry received heavy criticism for the constant requests for money. The Roberts were living an extravagance lifestyle while many of their supporters were not wealthy. Financial questions were raised in how Roberts used University endowment funds to purchase personal homes and cars.

In 1977 Roberts had a vision to build a hospital where people not only received care but received healing prayer. It was to be called City of Faith. Roberts put his heart and soul into the project, believing that God would build it as He had the University. The hospital struggled along and Roberts called his followers to give to the project, believing he had a vision from God to raise the money. Roberts even claimed twice that if money didn't come in that Jesus would "take him home." The hospital was built, but never succeeded financially, and finally closed in 1989. Financial giving was plummeting for both the Oral Roberts Evangelistic Association and Oral Roberts University.

Roberts retired in 1993, at the age of 75. Roberts, with his wife Evelyn, moved to California to live near the coast. Evelyn died in May 2005. Although Roberts influence waned after the problems of the 1970s and 1980s, he was still recognized for his pioneering work on the "sawdust trail", television evangelism, and building a Christian University. He often appeared on religious broadcasting networks as a recognized leader in the healing movement of the last half century. He died December 15, 2009 at the age of 91.

Oral Roberts' legacy is a mixed one. Roberts brought the truth of God's healing to the public in a way that few others accomplished in his lifetime. His financial and personal issues and increasingly extravagant claims eventually brought his ministry into disrepute. The University he established continued to have financial crises under the leadership of his son Richard Roberts. It was only after Richard stepped down in 2009 and new leadership took over the University that it stabilized financially. The University is no longer connected to the Oral Roberts Evangelistic Association.

The Difficult Habit of Quiet

The habit of quiet may be harder today than ever before. Don’t get me wrong: it’s always been hard. The rise and spread of technology, however, tends to crowd out quiet even more. Now that we can carry the whole wide and wild world in our pockets, it’s that much harder to keep the world at bay. Our phones always promise another update to see, image to like, website to visit, game to play, text to read, stream to watch, forecast to monitor, podcast to download, headline to scan, article to skim, score to check, price to compare. That kind of access, and semblance of control, can begin to make quiet moments feel like wasted ones. Who could sit and be still while so much life rushes by? Even if we don’t immediately pick up our phones, we’re often still held captive by them, wondering what new they might hold — what we might be missing. As hard as quiet might be to come by, however, it’s still a life-saving, soul-strengthening habit for any human soul. The God who made this wide and wild world, and who molded our finite and fragile frames, says of us, “In quietness and in trust shall be your strength” (Isaiah 30:15). In days filled with noise, do you still find time to be this kind of strong? Or has stress and distraction slowly eroded your spiritual health? How often do you stop to be quiet? What God Does with Quiet What kind of quietness produces strength? Not all quietness does. We could sell our televisions, give away our phones, move to the countryside, and still be as weak as ever. No, “in quietness and in trust shall be your strength.” The quiet we need is a quiet filled with God. Quietness becomes strength only when our stillness says that we need him. Be still, and know that I am God. I will be exalted among the nations, I will be exalted in the earth! (Psalm 46:10) This still, trusting quietness defies self-reliance. Quietness can preach reality to our souls like few habits can. It says that he is God, and we are not; he knows all, and we know little; he is strong, and we are weak. Quietness widens our eyes to the bigness of God and the smallness of us. It brings us low enough to see how high and wise and worthy he is. You can begin to see why quietness can be so hard. It’s deeply (sometimes ruthlessly) humbling. For it to say something true and beautiful about God, it first says something true and devastating about us. Our quietness says, “Without him, you can do nothing.” Our refusal to be quiet, on the other hand, says, “I can do a whole lot on my own” — and that feels good to hear. It just robs us of the real strength and help we might have found. God strengthens the quiet with his strength, because quietness turns weakness and neediness into worship (2 Corinthians 12:9–10). We get the strength and help and joy; he gets the glory. But You Were Unwilling The context of Isaiah’s words, however, is not inspiring, but sobering. God says to his people, “In returning and rest you shall be saved; in quietness and in trust shall be your strength.” But you were unwilling . . . (Isaiah 30:15–16) Quietness would have made them strong, but they wouldn’t have it. Assyria was bearing down on Judah, threatening to crush them as it had crushed many before them. And how do God’s people respond? “Ah, stubborn children,” declares the Lord, “who carry out a plan, but not mine, and who make an alliance, but not of my Spirit, that they may add sin to sin; who set out to go down to Egypt, without asking for my direction.” (Isaiah 30:1–2) Even after watching him deliver them so many times before, they cast his plan aside and made their own. They sought help, but not from him. They went back to Egypt (of all places!) and asked those who had enslaved and oppressed them to protect them. And they didn’t even stop to ask what God thought. They did, and did, and did, at every turn refusing to stop, be quiet, and receive the strength and support of God. I would rush to help you, God says, but you were unwilling. You weren’t patient or humble enough to receive my help. “How often do we choose activity over quietness, distraction over meditation, ‘productivity’ over prayer?” Why would they refuse the sovereign help of God? Deep down, we know why. Because they felt safer doing what they could do on their own than they did waiting to see what God might do. How often do we do the same? How often do we choose activity over quietness, distraction over meditation, “productivity” over prayer? How often do we try to solve our problems without slowing down enough to first seek God? Consequences of Avoiding Quiet Self-reliance is, of course, not as productive as it promises to be — at least not in the ways we would want. The people’s refusal to be quiet and ask God for help not only cut them off from his strength, but also invited other painful consequences. First, the sin of self-reliance breeds more sin. Again, God says in verse 1, “‘Ah, stubborn children,’ declares the Lord, ‘who carry out a plan, but not mine, and who make an alliance, but not of my Spirit, that they may add sin to sin.” The more we refuse the strength of God, the more we invite temptations to sin. Quiet keeps us close to God and aware of him. A scarcity of quiet pushes him to the margins of our hearts, making room for Satan to plant and tend lies within us. Second, their refusal to be quiet before God made them vulnerable to irrational fear. Because they fought in their own strength, the Lord says, “A thousand shall flee at the threat of one; at the threat of five you shall flee” (Isaiah 30:17). A lone soldier will send a thousand into a panic. The whole nation will crumble and surrender to just five men. In other words, you will be controlled and oppressed by irrational fears. You’ll run away when no one’s chasing you. You’ll lose sleep when there’s nothing to worry about. And right when you’re about to experience a breakthrough, you’ll despair and give up. Fears swell and flourish as long as God remains small and peripheral. Quiet time with God, however, scatters those fears by enlarging and inflaming our thoughts of him. The weightiest warning, however, comes in verse 13: those who forsake God’s word, God’s help, God’s way invite sudden ruin. “This iniquity shall be to you like a breach in a high wall, bulging out and about to collapse, whose breaking comes suddenly, in an instant.” Confidence in self drove a crack in the strongholds around them — a crack that grew and spread until the walls collapsed on top of them. All because they refused to embrace quiet and trust God. “In quietness and trust would be our strength; in busyness and pride will be our downfall.” For Judah, ruin meant falling into the cruel hands of the Assyrians. The walls will fall differently for us, but fall they will, if we let busyness and noise keep us from dependence. In quietness and trust would be our strength; in busyness and pride will be our downfall. Mercy for the Self-Reliant In the rhythms of our lives, do we make time to be quiet before God? Do we expect God to do more for us while we sit and pray than we can do by pushing through without him? If verse 15 humbles us — “But you were unwilling . . .” — verse 18 should humble us all the more. As Judah hurries and worries and strategizes and plans and recruits help and works overtime, all the while avoiding God, how does God respond to them? What is he doing while they refuse to stop doing and be quiet? Therefore the Lord waits to be gracious to you, and therefore he exalts himself to show mercy to you. For the Lord is a God of justice; blessed are all those who wait for him. (Isaiah 30:18) While we refuse to wait for him, God waits to be gracious to us. He’s not watching to see if he’ll be forced to show us mercy; he wants to show us mercy. The God of heaven, the one before time, above time, and beyond time, waits for us to ask for help. He loves to hear the sound of quiet trust. Blessed — happy — are those who wait for him, who know their need for him, who ask him for help, who find their strength in his strength, who learn to be and stay quiet before him. Article by Marshall Segal