Others like the meaning of marriage Features >>

The Intimate Marriage - A Practical Guide To Building A Great Marriage

The Meaning Of Marriage: A Couple’s Devotional

Celebrating Marriage

The Act Of Marriage

Healing For A Broken Heart

Making Marriage Work

The Abcs Of A Beautiful Marriage

Preparing For Marriage

This Momentary Marriage

The Marriage Builder

About the Book

"The Meaning of Marriage" by Timothy Keller explores the true essence of marriage as a spiritual partnership designed to bring two people closer to God. With insight drawn from Scripture and personal experiences, Keller delves into the importance of commitment, communication, and love within the context of marriage, offering practical advice and guidance for building a strong and lasting relationship.

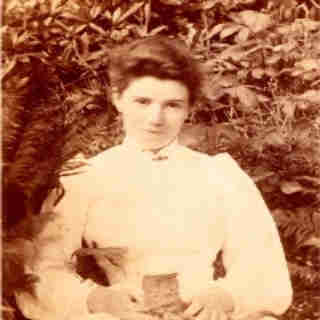

Amy Carmichael

Born in Belfast Ireland, to a devout family of Scottish ancestry, Carmichael was educated at home and in England, where she lived with the familt of Robert Wilson after her father’s death. While never officially adopted, she used the hyphenated name Wilson-Carmichael as late as 1912. Her missionary call came through contacts with the Keswick movement. In 1892 she volunteered to the China Inland Mission but was refused on health grounds. However, in 1893 she sailed for Japan as the first Keswick missionary to join the Church Missionary Society (CMS) work led by Barclay Buxton. After less than two years in Japan and Ceylon, she was back in England before the end of 1894. The next year she volunteered to the Church of England Zenana Missionary Society, and in November 1895 she arrived in South India, never to leave. While still learning the difficult Tamil language, she commenced itinerant evangelism with a band of Indian Christian women, guided by the CMS missionary Thomas Walker. She soon found herself responsible for Indian women converts, and in 1901, she, the Walkers, and their Indian colleagues settled in Dohnavur. During her village itinerations, she had become increasingly aware of the fact that many Indian children were dedicated to the gods by their parents or guardians, became temple children, and lived in moral and spiritual danger. It became her mission to rescue and raise these children, and so the Dohnavur Fellowship came into being (registered 1927). Known at Dohnavur as Amma (Mother), Carmichael was the leader, and the work became well known through her writing. Workers volunteered and financial support was received, though money was never solicited. In 1931 she had a serious fall, and this, with arthritis, kept her an invalid for the rest of her life. She continued to write, and identified leaders, missionary and Indian, to take her place. The Dohnavur Fellowship still continues today.

Jocelyn Murray, “Carmichael, Amy Beatrice,” in Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions, ed. Gerald H. Anderson (New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 1998), 116.

This article is reprinted from Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions, Macmillan Reference USA, copyright © 1998 Gerald H. Anderson, by permission of Macmillan Reference USA, New York, NY. All rights reserved.

“Ammai” of orphans and holiness author

Amy Carmichael was born in Ireland in 1867, the oldest of seven children. As a teen, she attended a Wesleyan Methodist girls boarding school, until her father died when she was 18. Carmichael twice attended Keswick Conventions and experienced a holiness conversion which led her to work among the poor in Belfast. Through the Keswick Conventions, Carmichael met Robert Wilson. He developed a close relationship with the young woman, and invited her to live with his family. Carmichael soon felt a call to mission work and applied to the China Inland Mission as Amy Carmichael-Wilson. Although she did not go to China due to health reasons, Carmichael did go to Japan for a brief period of time. There she dressed in kimonos and began to learn Japanese. Her letters home from Japan became the basis for her first book, From Sunrise Land. Carmichael left Japan due to health reasons, eventually returning to England. She soon accepted a position with the Church of England’s Zenana Missionary Society, serving in India. From 1895 to 1925, her work with orphans in Tinnevelly (now Tirunelveli) was supported by the Church of England. After that time, Carmichael continued her work in the faith mission style, establishing an orphanage in Dohnavur. The orphanage first cared for girls who had been temple girls, who would eventually become temple prostitutes. Later the orphanage accepted boys as well.

Carmichael never returned to England after arriving in India. She wrote prolifically, publishing nearly 40 books. In her personal devotions, she relied on scripture and poetry. She wrote many of her own poems and songs. Carmichael had a bad fall in 1931, which restricted her movement. She stayed in her room, writing and studying. She often quoted Julian of Norwich when she wrote of suffering and patience. Many of Carmichael’s books have stories of Dohnavur children, interspersed with scripture, verses, and photographs of the children or nature. Carmichael never directly asked for funding, but the mission continued to be supported through donations. In 1951 Carmichael died at Dohnavur. Her headstone is inscribed “Ammai”, revered mother, which the children of Dohnavur called Carmichael.

Carmichael’s lengthy ministry at Dohnavur was sustained through her strong reliance upon scripture and prayer. Her early dedication to holiness practices and her roots in the Keswick tradition helped to guide her strong will and determination in her mission to the children of southern India.

by Rev. Lisa Beth White

Born in Belfast Ireland, to a devout family of Scottish ancestry, Carmichael was educated at home and in England, where she lived with the familt of Robert Wilson after her father’s death. While never officially adopted, she used the hyphenated name Wilson-Carmichael as late as 1912. Her missionary call came through contacts with the Keswick movement. In 1892 she volunteered to the China Inland Mission but was refused on health grounds. However, in 1893 she sailed for Japan as the first Keswick missionary to join the Church Missionary Society (CMS) work led by Barclay Buxton. After less than two years in Japan and Ceylon, she was back in England before the end of 1894. The next year she volunteered to the Church of England Zenana Missionary Society, and in November 1895 she arrived in South India, never to leave. While still learning the difficult Tamil language, she commenced itinerant evangelism with a band of Indian Christian women, guided by the CMS missionary Thomas Walker. She soon found herself responsible for Indian women converts, and in 1901, she, the Walkers, and their Indian colleagues settled in Dohnavur. During her village itinerations, she had become increasingly aware of the fact that many Indian children were dedicated to the gods by their parents or guardians, became temple children, and lived in moral and spiritual danger. It became her mission to rescue and raise these children, and so the Dohnavur Fellowship came into being (registered 1927). Known at Dohnavur as Amma (Mother), Carmichael was the leader, and the work became well known through her writing. Workers volunteered and financial support was received, though money was never solicited. In 1931 she had a serious fall, and this, with arthritis, kept her an invalid for the rest of her life. She continued to write, and identified leaders, missionary and Indian, to take her place. The Dohnavur Fellowship still continues today.

Jocelyn Murray, “Carmichael, Amy Beatrice,” in Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions, ed. Gerald H. Anderson (New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 1998), 116.

This article is reprinted from Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions, Macmillan Reference USA, copyright © 1998 Gerald H. Anderson, by permission of Macmillan Reference USA, New York, NY. All rights reserved.

“Ammai” of orphans and holiness author

Amy Carmichael was born in Ireland in 1867, the oldest of seven children. As a teen, she attended a Wesleyan Methodist girls boarding school, until her father died when she was 18. Carmichael twice attended Keswick Conventions and experienced a holiness conversion which led her to work among the poor in Belfast. Through the Keswick Conventions, Carmichael met Robert Wilson. He developed a close relationship with the young woman, and invited her to live with his family. Carmichael soon felt a call to mission work and applied to the China Inland Mission as Amy Carmichael-Wilson. Although she did not go to China due to health reasons, Carmichael did go to Japan for a brief period of time. There she dressed in kimonos and began to learn Japanese. Her letters home from Japan became the basis for her first book, From Sunrise Land. Carmichael left Japan due to health reasons, eventually returning to England. She soon accepted a position with the Church of England’s Zenana Missionary Society, serving in India. From 1895 to 1925, her work with orphans in Tinnevelly (now Tirunelveli) was supported by the Church of England. After that time, Carmichael continued her work in the faith mission style, establishing an orphanage in Dohnavur. The orphanage first cared for girls who had been temple girls, who would eventually become temple prostitutes. Later the orphanage accepted boys as well.

Carmichael never returned to England after arriving in India. She wrote prolifically, publishing nearly 40 books. In her personal devotions, she relied on scripture and poetry. She wrote many of her own poems and songs. Carmichael had a bad fall in 1931, which restricted her movement. She stayed in her room, writing and studying. She often quoted Julian of Norwich when she wrote of suffering and patience. Many of Carmichael’s books have stories of Dohnavur children, interspersed with scripture, verses, and photographs of the children or nature. Carmichael never directly asked for funding, but the mission continued to be supported through donations. In 1951 Carmichael died at Dohnavur. Her headstone is inscribed “Ammai”, revered mother, which the children of Dohnavur called Carmichael.

Carmichael’s lengthy ministry at Dohnavur was sustained through her strong reliance upon scripture and prayer. Her early dedication to holiness practices and her roots in the Keswick tradition helped to guide her strong will and determination in her mission to the children of southern India.

by Rev. Lisa Beth White

The Awl

I saw a good Samaritan Slow down and stop. “This is that kind of road; and none Of my sweet business here.” Atop The hill just to the east he saw The restful spires Of Jericho. “There is no law,” He thought, “no statute that requires My bother, let alone the chance Of injury.” But conscience rose and put a glance Of his own son for him to see Before his father-eyes. He crossed The lonely road, And whispered to himself, “The cost Of this assault is not his load Alone. Perhaps his father waits In Jericho.” He knelt. “Such are the fates Samaritans endure.” Then, “No! This is a Jew!” And worse, much worse: The man was dead. “Now what?” he thought. “It is a curse To die and rot without a bed Beneath the ground. And he is young. His father will Be searching soon, perhaps.” He clung To one small metal awl until, In his dead hand, it pierced his skin, As if to say To highway thieves: “Not this, not in My life will this be snatched away.” The good Samaritan put him Upon his beast, And set his face to do the grim, Bleak work of bearing the deceased Up to Jerusalem to find A leather row Where some young tanner had been signed To take a load to Jericho. He stopped at the first shop, “Can you Say if a man Was sent with leather goods down through The road to Jericho?” “I can. But hardly yet a man! In age, Or worth, I think. For all I know, his grief and rage Drove him to steal the lot, and drink His sorry way to Gerasa. His father’s sick With fear. There was a bruhaha The night he left. He tried to stick A man because his mother’s name Was smeared. He slashed Him with a tanner’s awl. He came By here to get his load, and lashed It to his mule and disappeared. His mother died Last year. The old man with the beard, Down at the corner, right hand side, That’s his dad.” “Thank you.” Hesitant, And burdened down With death, he waited at the front, Until the old man, with a frown, Said, “What you got for sale there, sir?” “It’s not for sale, Or trade, or deals. But if it were, You’d pay me anything. This veil Lies on the treasure of your life: Your son. And in His hand, unstolen in the strife. There is an awl thrust through his skin.” The old man lifted up the cloak, And put it back. “I found him on the road.” “Your folk Hate Jews, my friend. And there’s no lack Of corpses on that road. What do You want from me For this?” “I want to know from you About the awl. And I would be Obliged if you would tell me what It means.” “All right. A year ago, tonight, we shut His mother’s eyes. And every light Went out for him. But just before She died, she called Him. It was early, and a score Of birds were singing. So enthralled, She seemed, then said to him, ‘My child, With singing birds, I give you now my awl.’” He smiled, “She always had a way with words.” John Piper