Others like the act of marriage Features >>

Healing Your Marriage When Trust Is Broken

The Abcs Of A Beautiful Marriage

The Intimate Marriage - A Practical Guide To Building A Great Marriage

A Marriage Without Regrets

The Meaning Of Marriage: A Couple’s Devotional

The Scarlet Thread

Marriage On The Rock - God's Design For Your Dream Marriage

-160.webp)

Couple Skills: Making Your Relationship Work

The Christian Parenting Handbook

Your Marriage And Your Ancestry

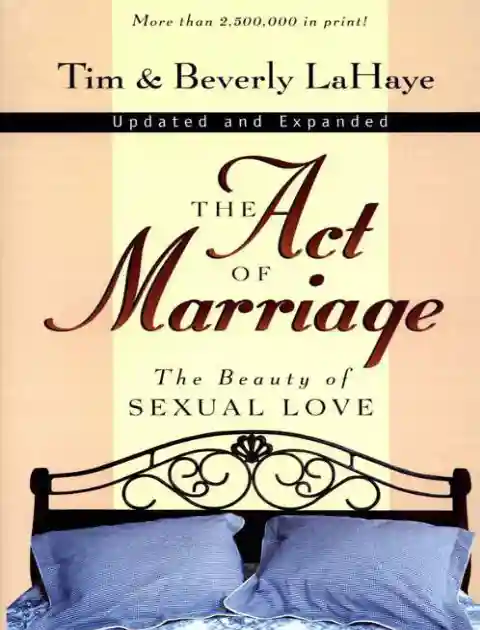

About the Book

"The Act of Marriage" by Tim LaHaye is a Christian guidebook on marriage and sexuality, offering advice on building a strong, fulfilling relationship with one's spouse. LaHaye explores topics such as communication, intimacy, and sexual satisfaction within the context of marriage, providing practical tips and biblical guidance for couples looking to strengthen their bond and cultivate a healthy sexual relationship.

Robert Murray McCheyne

What Does It Mean to Be Real

Nobody likes a fake. Even in our airbrush culture, we despise counterfeits and crave authenticity. Everyone wants to be real. But what does it mean to be real? No one really knows. Or so it seems. Try an experiment. Listen to people talk about what it means to be a Christian. Do you know what you will hear? Lots of competing answers and plenty of confusion. Perhaps you recall when 2012 presidential hopeful, Senator Rick Santorum, claimed that President Barack Obama’s policies were based on “a different theology.” Reporters, of course, pounced on this juicy piece of journalist red meat. “Did Senator Santorum,” they asked, “have the audacity, not of hope, but political incorrectness, to call into question the president’s claim to be a Christian?” When Senator Santorum was pressed, he gave a politically savvy response: “If the president says he’s a Christian, he’s a Christian.” End of story. Next question, please. His answer satisfied reporters, and thousands of others following the story. It was as if he said, “To profess faith is to possess faith.” And what could be less objectionable, or more American, than that? But one wonders what Jesus thinks of what Santorum said. More Than Mere Talk Is it enough simply to say we’re real, or should we be able to see we’re real? And if so, what should we see? Are there marks of authentic faith we should see in our lives, or in the lives of others? And what about the watching world? What should they see in the lives of real Christians? Now, more than a decade into the twenty-first century, the evangelical church faces huge challenges to its ministry and mission — radical pluralism, aggressive secularism, political polarization, skepticism about religion, revisionist sexual ethics, postmodern conceptions of truth. But perhaps the greatest threat to the church’s witness is one of our own making — an image problem. Many outside the church view Christians as unchristian in their attitudes and actions — bigoted, homophobic, hypocritical, materialistic, judgmental, self-serving, overly political. Several years ago, David Kinnaman and Gabe Lyons showed this in their book Unchristian , which landed like a bombshell on a happy-go-lucky evangelicalism, causing many of us to do some serious soul-searching. The evangelical church’s image problem doesn’t bode well for its future. In fact, the data suggests that evangelical Christianity is declining in North America. Despite the church’s best efforts to appeal to the disillusioned, we continue to see alarming trends. Droves of people, especially from younger generations, are leaving the church and don’t plan to return. This has driven some to even predict the end of evangelicalism (See David Fitch, The End of Evangelicalism? ). One True Soil The reasons for this discouraging state of affairs are complex, not cookie-cutter. But we know one thing is certain: When Christians are confused about what it means to be real, the spiritual decline of the church will follow. In our increasingly post-Christian culture, where confusion about what it means to be real abounds, and where distrust of organized religion has reached an all-time high, the church needs to get real . We must clarify for ourselves, and for a watching world, what it means to live a life of authentic faith. While Christians are confused about what it means to be real, Jesus is not. “Thus you will recognize them by their fruits,” he says (Matthew 7:20). You know you’re real if you bear fruit, he tells us. Fruit is the telltale sign of authentic faith because fruit doesn’t lie. “For no good tree bears bad fruit, nor again does a bad tree bear good fruit, for each tree is known by its own fruit. For figs are not gathered from thornbushes, nor are grapes picked from a bramble bush” (Luke 6:43–44). Jesus underscores this point in his famous parable about the sower (Matthew 13:1–23). The parable itself is straightforward. A farmer sows seed in a field, and the seed represents the good news of the kingdom. It is sown on four different kinds of soil, each representing a different response to the message of the kingdom. Simple enough, right? But here’s the punch line: Only one type of soil bears fruit. Counterfeits Exposed The seed sown on the first soil hardly gets started. Satan comes and snatches it away. But what’s even more troubling is the outcome of the seed sown on the second and third soils. Why? Because both respond positively to the message, at least initially. These seeds appear to take root and begin growing into something real. Yet as the story continues, we learn that neither seed bears fruit. Neither lasts to the end, and thus neither seed is real. Some of the seeds fail to develop roots, and they don’t persevere when life gets hard and their faith is tested. All we see from this seed is a burst of enthusiasm, but no staying power. Perhaps this is someone who got excited about fellowship or forgiveness, but lacked love for Christ. They only have the appearance of being real. Over time, their faith proved counterfeit. We assume the third seed had a similarly joyful response to the message. Yet this soon dissipates because of revived interest in the things of the world — a career promotion, a new vacation home, saving toward their 401(k) plan. These concerns choke any fledgling faith, and the person falls away. New People with New Lives Why does Jesus tell his disciples this sobering parable? Why such a blunt story about the distinction between authentic and inauthentic responses to his message? Evidently, Jesus doesn’t equate professing faith with possessing faith, as we so often do. Instead, he warns his disciples that only one things matters — bearing fruit Although provocative, I think Jesus’s point is simple. Real is something you can see. There is a visible difference between real and not-real Christians. It’s not enough to say you’re real; you should be able to see you’re real. Real faith is something you can see. Being real is more than regularly attending church, feeling good about God, or “accepting” Jesus as your Savior; it goes beyond being baptized, receiving Communion, reciting the creed, or joining in church membership. As important as these things are, being real runs deeper than these things. Real Christians are new creatures. Physically, they won’t look different than others, at least not in the way they dress or keep their hair. Yet real Christians are radically changed — they’ve experienced a new birth, received a new heart, and enjoy new desires. Which makes them altogether new people who live new lives. And it shows. If you’re real, it will reveal itself in your life. Real Christians bear the marks of authentic faith in ways that can be seen, heard, and felt. When you know what you’re looking for, you can see the marks of real in their lives — and in your own.