Take Possession Of Your Inheritance Order Printed Copy

- Author: Morris Cerullo

- Size: 1.28MB | 49 pages

- |

Others like take possession of your inheritance Features >>

About the Book

"Take Possession of Your Inheritance" by Morris Cerullo is a guide to help readers understand and access the spiritual inheritance that has been promised to them by God. Cerullo shares strategies and principles for overcoming obstacles and claiming the blessings that are rightfully theirs, offering practical advice on how to live a life of abundance and fulfillment. Through personal stories and biblical teachings, Cerullo inspires readers to have faith, believe in themselves, and take ownership of the abundant life that God has promised them.

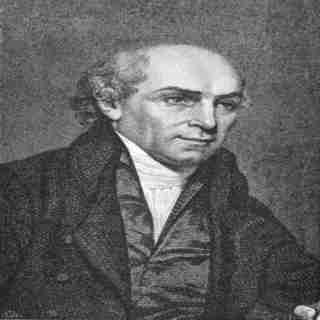

William Carey

"Expect great things; attempt great things."

At a meeting of Baptist leaders in the late 1700s, a newly ordained minister stood to argue for the value of overseas missions. He was abruptly interrupted by an older minister who said, "Young man, sit down! You are an enthusiast. When God pleases to convert the heathen, he'll do it without consulting you or me."

That such an attitude is inconceivable today is largely due to the subsequent efforts of that young man, William Carey.

Plodder Carey was raised in the obscure, rural village of Paulerpury, in the middle of England. He apprenticed in a local cobbler's shop, where the nominal Anglican was converted. He enthusiastically took up the faith, and though little educated, the young convert borrowed a Greek grammar and proceeded to teach himself New Testament Greek.

When his master died, he took up shoemaking in nearby Hackleton, where he met and married Dorothy Plackett, who soon gave birth to a daughter. But the apprentice cobbler's life was hard—the child died at age 2—and his pay was insufficient. Carey's family sunk into poverty and stayed there even after he took over the business.

"I can plod," he wrote later, "I can persevere to any definite pursuit." All the while, he continued his language studies, adding Hebrew and Latin, and became a preacher with the Particular Baptists. He also continued pursuing his lifelong interest in international affairs, especially the religious life of other cultures.

Carey was impressed with early Moravian missionaries and was increasingly dismayed at his fellow Protestants' lack of missions interest. In response, he penned An Enquiry into the Obligations of Christians to Use Means for the Conversion of the Heathens. He argued that Jesus' Great Commission applied to all Christians of all times, and he castigated fellow believers of his day for ignoring it: "Multitudes sit at ease and give themselves no concern about the far greater part of their fellow sinners, who to this day, are lost in ignorance and idolatry."

Carey didn't stop there: in 1792 he organized a missionary society, and at its inaugural meeting preached a sermon with the call, "Expect great things from God; attempt great things for God!" Within a year, Carey, John Thomas (a former surgeon), and Carey's family (which now included three boys, and another child on the way) were on a ship headed for India.

Stranger in a strange land

Thomas and Carey had grossly underestimated what it would cost to live in India, and Carey's early years there were miserable. When Thomas deserted the enterprise, Carey was forced to move his family repeatedly as he sought employment that could sustain them. Illness racked the family, and loneliness and regret set it: "I am in a strange land," he wrote, "no Christian friend, a large family, and nothing to supply their wants." But he also retained hope: "Well, I have God, and his word is sure."

He learned Bengali with the help of a pundit, and in a few weeks began translating the Bible into Bengali and preaching to small gatherings.

When Carey himself contracted malaria, and then his 5-year-old Peter died of dysentery, it became too much for his wife, Dorothy, whose mental health deteriorated rapidly. She suffered delusions, accusing Carey of adultery and threatening him with a knife. She eventually had to be confined to a room and physically restrained.

"This is indeed the valley of the shadow of death to me," Carey wrote, though characteristically added, "But I rejoice that I am here notwithstanding; and God is here."

Gift of tongues

In October 1799, things finally turned. He was invited to locate in a Danish settlement in Serampore, near Calcutta. He was now under the protection of the Danes, who permitted him to preach legally (in the British-controlled areas of India, all of Carey's missionary work had been illegal).

Carey was joined by William Ward, a printer, and Joshua and Hanna Marshman, teachers. Mission finances increased considerably as Ward began securing government printing contracts, the Marshmans opened schools for children, and Carey began teaching at Fort William College in Calcutta.

In December 1800, after seven years of missionary labor, Carey baptized his first convert, Krishna Pal, and two months later, he published his first Bengali New Testament. With this and subsequent editions, Carey and his colleagues laid the foundation for the study of modern Bengali, which up to this time had been an "unsettled dialect."

Carey continued to expect great things; over the next 28 years, he and his pundits translated the entire Bible into India's major languages: Bengali, Oriya, Marathi, Hindi, Assamese, and Sanskrit and parts of 209 other languages and dialects.

He also sought social reform in India, including the abolition of infanticide, widow burning (sati), and assisted suicide. He and the Marshmans founded Serampore College in 1818, a divinity school for Indians, which today offers theological and liberal arts education for some 2,500 students.

By the time Carey died, he had spent 41 years in India without a furlough. His mission could count only some 700 converts in a nation of millions, but he had laid an impressive foundation of Bible translations, education, and social reform.

His greatest legacy was in the worldwide missionary movement of the nineteenth century that he inspired. Missionaries like Adoniram Judson, Hudson Taylor, and David Livingstone, among thousands of others, were impressed not only by Carey's example, but by his words "Expect great things; attempt great things." The history of nineteenth-century Protestant missions is in many ways an extended commentary on the phrase.

"Expect great things; attempt great things."

At a meeting of Baptist leaders in the late 1700s, a newly ordained minister stood to argue for the value of overseas missions. He was abruptly interrupted by an older minister who said, "Young man, sit down! You are an enthusiast. When God pleases to convert the heathen, he'll do it without consulting you or me."

That such an attitude is inconceivable today is largely due to the subsequent efforts of that young man, William Carey.

Plodder Carey was raised in the obscure, rural village of Paulerpury, in the middle of England. He apprenticed in a local cobbler's shop, where the nominal Anglican was converted. He enthusiastically took up the faith, and though little educated, the young convert borrowed a Greek grammar and proceeded to teach himself New Testament Greek.

When his master died, he took up shoemaking in nearby Hackleton, where he met and married Dorothy Plackett, who soon gave birth to a daughter. But the apprentice cobbler's life was hard—the child died at age 2—and his pay was insufficient. Carey's family sunk into poverty and stayed there even after he took over the business.

"I can plod," he wrote later, "I can persevere to any definite pursuit." All the while, he continued his language studies, adding Hebrew and Latin, and became a preacher with the Particular Baptists. He also continued pursuing his lifelong interest in international affairs, especially the religious life of other cultures.

Carey was impressed with early Moravian missionaries and was increasingly dismayed at his fellow Protestants' lack of missions interest. In response, he penned An Enquiry into the Obligations of Christians to Use Means for the Conversion of the Heathens. He argued that Jesus' Great Commission applied to all Christians of all times, and he castigated fellow believers of his day for ignoring it: "Multitudes sit at ease and give themselves no concern about the far greater part of their fellow sinners, who to this day, are lost in ignorance and idolatry."

Carey didn't stop there: in 1792 he organized a missionary society, and at its inaugural meeting preached a sermon with the call, "Expect great things from God; attempt great things for God!" Within a year, Carey, John Thomas (a former surgeon), and Carey's family (which now included three boys, and another child on the way) were on a ship headed for India.

Stranger in a strange land

Thomas and Carey had grossly underestimated what it would cost to live in India, and Carey's early years there were miserable. When Thomas deserted the enterprise, Carey was forced to move his family repeatedly as he sought employment that could sustain them. Illness racked the family, and loneliness and regret set it: "I am in a strange land," he wrote, "no Christian friend, a large family, and nothing to supply their wants." But he also retained hope: "Well, I have God, and his word is sure."

He learned Bengali with the help of a pundit, and in a few weeks began translating the Bible into Bengali and preaching to small gatherings.

When Carey himself contracted malaria, and then his 5-year-old Peter died of dysentery, it became too much for his wife, Dorothy, whose mental health deteriorated rapidly. She suffered delusions, accusing Carey of adultery and threatening him with a knife. She eventually had to be confined to a room and physically restrained.

"This is indeed the valley of the shadow of death to me," Carey wrote, though characteristically added, "But I rejoice that I am here notwithstanding; and God is here."

Gift of tongues

In October 1799, things finally turned. He was invited to locate in a Danish settlement in Serampore, near Calcutta. He was now under the protection of the Danes, who permitted him to preach legally (in the British-controlled areas of India, all of Carey's missionary work had been illegal).

Carey was joined by William Ward, a printer, and Joshua and Hanna Marshman, teachers. Mission finances increased considerably as Ward began securing government printing contracts, the Marshmans opened schools for children, and Carey began teaching at Fort William College in Calcutta.

In December 1800, after seven years of missionary labor, Carey baptized his first convert, Krishna Pal, and two months later, he published his first Bengali New Testament. With this and subsequent editions, Carey and his colleagues laid the foundation for the study of modern Bengali, which up to this time had been an "unsettled dialect."

Carey continued to expect great things; over the next 28 years, he and his pundits translated the entire Bible into India's major languages: Bengali, Oriya, Marathi, Hindi, Assamese, and Sanskrit and parts of 209 other languages and dialects.

He also sought social reform in India, including the abolition of infanticide, widow burning (sati), and assisted suicide. He and the Marshmans founded Serampore College in 1818, a divinity school for Indians, which today offers theological and liberal arts education for some 2,500 students.

By the time Carey died, he had spent 41 years in India without a furlough. His mission could count only some 700 converts in a nation of millions, but he had laid an impressive foundation of Bible translations, education, and social reform.

His greatest legacy was in the worldwide missionary movement of the nineteenth century that he inspired. Missionaries like Adoniram Judson, Hudson Taylor, and David Livingstone, among thousands of others, were impressed not only by Carey's example, but by his words "Expect great things; attempt great things." The history of nineteenth-century Protestant missions is in many ways an extended commentary on the phrase.

Am I Really a Christian

Am I really a Christian? Perhaps for you, that question looms like a shadow in the back of the soul, threatening your dearest hopes and peace. Others may struggle to understand why. You bear all the outward marks of a Christian: You read, pray, and gather with your church faithfully. You serve and sacrifice your time. You look for opportunities to share Christ with neighbors. You hide no secret sins. But “the heart knows its own bitterness” (Proverbs 14:10), and so too its own darkness. No matter how much you obey on the outside, when you look within you find a mass of conflicting desires and warring ambitions. Every godly impulse seems mixed with an ungodly one; every holy desire with something shameful. You can’t pray earnestly without feeling proud of yourself afterward. You can’t serve without some part of you wanting to be praised. You remember Judas and Demas, men whose outward appearance deceived others and deceived themselves. You know that on the last day many will find themselves surprised, knocking on the door of heaven only to hear four haunting words: “I never knew you” (Matthew 7:23; 25:11–12). And so, in the stillness before sleep, in quiet moments of the day, and sometimes in the middle of worship itself, the shadow returns: Am I real — or am I just deceiving myself? ‘With You There Is Forgiveness’ Sometimes, the most apt answers to our most pressing questions are buried hundreds of years ago. And when it comes to assurance in particular, we may never surpass the pastoral wisdom of those seventeenth-century soul physicians, the Puritans. Assurance proved to be a common struggle for the Christians of that era, such that John Owen devoted over three hundred pages to the topic in his masterful Exposition of Psalm 130, most of which addresses a single verse: “With you there is forgiveness, that you may be feared” (Psalm 130:4). “When it comes to assurance, what matters most is not sin’s persistence, but our resistance.” With God there is forgiveness — free forgiveness, abundant forgiveness, glad forgiveness, based on the blood and righteousness of Jesus Christ. But Owen knew that some Christians would hesitate to believe that forgiveness was for them. He knew that some introspective believers, bruised with a sense of their indwelling sin, would respond, “Yes, there is forgiveness with God, but I see so much darkness within myself — is there forgiveness for me?” In a way, Owen’s entire book is his answer to that question. But he devotes special attention to such believers in one brief section — not aiming, necessarily, to remove every doubt (something only God can do), but merely to help readers see themselves from a new, more gracious angle. Grief can be a good sign. When some Christians search their hearts, they have eyes only for their sin. Their highest worship seems tainted with self-focus; their best obedience seems spoiled by strains of insincerity. They are ready to sigh with David, “My iniquities have overtaken me, and I cannot see; they are more than the hairs of my head; my heart fails me” (Psalm 40:12). But such grief can be a good sign. Owen asks us to imagine a man with a numb leg. As long as his leg has lost sensation, the man “endures deep cuts and lancings, and feels them not.” Yet as soon as his nerves awake, he “feels the least cut, and may think the instruments sharper than they were before, when all the difference is, that he hath got a quickness of sense” (Works of John Owen, 6:604). Outside of Christ, our souls are numb to the evil of sin. The guilt and the consequences of sin may have wounded us from time to time, but its evil we could hardly feel (if at all) — no matter how often it thrust us through. But once our souls come alive, we need only a paper cut to wince. Sin burdens us, oppresses us, grieves us, not because we are worse than we were before, but because we finally feel sin for what it is: the thorns that crowned our Savior’s head, the spear that pierced our Lord. So, Owen writes, “‘Oh wretched man that I am! who shall deliver me from the body of this death?’ [Romans 7:24] is a better evidence of grace and holiness than ‘God, I thank thee I am not as other men’ [Luke 18:11]” (601). Grief over our sin, far from disqualifying us from the kingdom, suggests that comfort is on the way (Matthew 5:4). Your resistance, not sin’s persistence, matters most. Temptation is frustratingly persistent. Sin would grieve us less if it left us alone more often: if pride were not ready to rise on all occasions, if anger did not flame up from the smallest sparks, if foolish thoughts did not fill our minds so often. Can we have any confidence of assurance if we find sin so relentlessly tempting? Owen takes us to 1 Peter 2:11, where the apostle writes, “Abstain from the passions of the flesh, which wage war against your soul.” He comments, “Now, to war is not to make faint or gentle opposition, . . . but it is to go out with great strength, to use craft, subtlety, and force, so as to put the whole issue to a hazard. So these lusts war” (605). “God’s ‘well done’ says less about the worth of our works than about the wonder of his mercy.” Sin wars — and not against those whom it holds captive, but against those who have been rescued from its authority and now fight below Christ’s banner. When it comes to assurance, then, what matters most is not sin’s persistence, but our resistance. Or as Owen puts it, “Your state is not at all to be measured by the opposition that sin makes to you, but by the opposition you make to it” (605). Sin may burden and tempt you, oppose and oppress you. Every army does. But do you, for your part, resist? Do you run up the watchtower and raise an alarm? Do you grip your shield and swing your sword? Do you labor, strive, watch, pray, and keep close to your Captain? Then sin’s warfare against you may be a sign that you are in Christ’s service. Christ purifies our obedience. The most sensitive Christians, Owen writes, often “find their hearts weak, and all their duties worthless. . . . In the best of them there is such a mixture of self, hypocrisy, unbelief, vain-glory, that they are even ashamed and confounded with the remembrance of them” (600). Whatever fruit they bear seems covered with the mold of indwelling sin. But often, God sees more grace in his sin-burdened people than they see in themselves. Remember Sarah, Owen says: even when she was walking in unbelief, God took notice of the fact — a trifle in our eyes — that she called her husband “lord” (Genesis 18:12; 1 Peter 3:6). So too, on the last day, Jesus will commend his people for good works they have long forgotten and struggle even to recognize (Matthew 25:37–40). Of course, God’s “well done” says less about the worth of our works than about the wonder of his mercy. Our Father hangs our pictures upon his wall because Christ adorns them with the jewels of his own crown. Owen writes, Jesus Christ takes whatever is evil and unsavoury out of them, and makes them acceptable. . . . All the ingredients of self that are in them on any account he takes away, and adds incense to what remains, and presents it to God. . . . So that God accepts a little, and Christ makes our little a great deal. (603) The only works that God accepts are those that have been washed in the blood of Jesus (Revelation 7:14). And any work that is washed in the blood of Jesus becomes transfigured, a small but resplendent reflection of “Christ in you, the hope of glory” (Colossians 1:27). And therefore God, in unspeakable grace, “remembers the duties which we forget, and forgets the sins which we remember” (603). Assurance arises from faith. Owen’s final piece of counsel may feel counterintuitive to the unassured heart. Many who struggle with assurance hesitate to rest their full weight on Christ’s saving promises until they feel some warrant from within that the promises belong to them. They wait to come boldly to the throne of grace until they find something to bring with them. But this gets the order exactly backward. Owen writes, “Do not resolve not to eat thy meat until thou art strong, when thou hast no means of being strong but by eating” (603). When we wait to focus our gaze on Christ’s promises until we are holy enough, we are like a man waiting to eat until he becomes strong, or waiting to sleep until he feels energized, or waiting to study until he grows wise. Sinclair Ferguson, a modern-day pupil of Owen, puts it this way: Believing [gives] rise to obedience, not obedience . . . to assurance irrespective of believing. Such faith cannot be forced into us by our efforts to be obedient; it arises only from larger and clearer views of Christ. (The Whole Christ, 204) The faith that nourishes both obedience and assurance arises only from larger and clearer views of Christ. If we stay away from Jesus until we are holy enough, we will stay away forever. But if we come to him right now and every morning hereafter, no matter how dead we feel, looking for welcome on the basis of his blood rather than our efforts, then we can hope, in time, to find faith flowering in fuller obedience and deeper assurance. But we will come only if we know, with Owen, that “with you there is forgiveness, that you may be feared” (Psalm 130:4). All who come to Christ, trust in Christ, and embrace Christ find the forgiveness that is with Christ. And you are no exception. Article by Scott Hubbard

.epub-160.webp)

-160.webp)