Others like jesus the son of man Features >>

Apostle J. A. Babalola Miraculous Journey

William Branham: A Man Sent By God

-160.webp)

The Myth Of The Twelve Tribes Of Israel (New Identities Across Time And Space)

The Untold Story Of A Young Billy Graham

Foxes Books Of Martyrs

Just As I Am: The Autobiography Of Billy Graham

Elisabeth Elliot: Joyful Surrender

God's Generals: The Missionaries

God's Generals: The Revivalists

Smith Wigglesworth: Apostle Of Faith

About the Book

"Jesus the Son of Man" by Kahlil Gibran is a poetic and philosophical exploration of the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. Through Gibran's lyrical prose, readers are encouraged to reflect on Jesus' humanity, compassion, and spiritual wisdom. The book offers a unique perspective on the life of Jesus, emphasizing his message of love, compassion, and forgiveness.

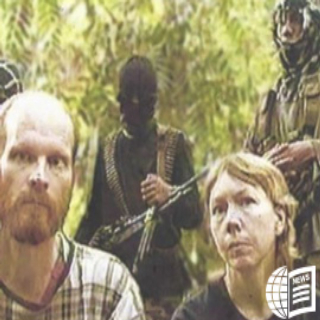

Martin and Gracia Burnham

Martin Burnham and Gracia were missionaries who served for 17 years in the Philippines. After their marriage, they underwent hard training in the jungle to prepare themselves to serve in jungle parts. Martin, being a pilot missionary, supported other missionaries who were working among the tribals in jungles. He delivered groceries and medicines to missionaries and tribals and transported sick people to medical facilities. He always had a big heart for tribals and missionaries. Gracia supported him well in the work.

On May 29, 2001, while relaxing at a resort after Martin’s one overseas mission, a Muslim militant group called the Abu Sayyaf Group attacked the resort and abducted the missionary couple and few others for ransom. The missionaries were kept captive for more than a year.

During that one year, the couple went through terrible experiences. They suffered starvation, sleeplessness and sickness, witnessed atrocities of militants and experienced gun battles between militants and the military. Amidst suffering, God was their only hope and strength.

At some point, Gracia was so depressed that although she believed that Christ died for her, she felt God doesn’t love her anymore. Martin said to her “either you believe it all or don’t believe it at all.” They encouraged one another to stand firm in the faith.

Martin Burnham and Gracia ministry in Philippines

Finally, on June 7, 2002, in a rescue operation by the Philippine military, wounded Gracia was rescued. But 42 years old Martin died in the gunfight during the rescue. Later, Gracia went back to America and joined her children.

Gracia did not let her painful experiences depress her and move her away from God. But she used those experiences to encourage others who are going through hardships. She founded the Martin and Gracia Burnham Foundation, which supports missionary aviation and tribal mission work around the world. It also focuses on ministries among Muslims. She forgave who abducted them, visited them in jail and shared Christ’s love. Some of them accepted Christ. Gracia believes that this may be God’s great purpose behind their suffering.

Martin Burnham and Gracia were missionaries who served for 17 years in the Philippines. After their marriage, they underwent hard training in the jungle to prepare themselves to serve in jungle parts. Martin, being a pilot missionary, supported other missionaries who were working among the tribals in jungles. He delivered groceries and medicines to missionaries and tribals and transported sick people to medical facilities. He always had a big heart for tribals and missionaries. Gracia supported him well in the work.

On May 29, 2001, while relaxing at a resort after Martin’s one overseas mission, a Muslim militant group called the Abu Sayyaf Group attacked the resort and abducted the missionary couple and few others for ransom. The missionaries were kept captive for more than a year.

During that one year, the couple went through terrible experiences. They suffered starvation, sleeplessness and sickness, witnessed atrocities of militants and experienced gun battles between militants and the military. Amidst suffering, God was their only hope and strength.

At some point, Gracia was so depressed that although she believed that Christ died for her, she felt God doesn’t love her anymore. Martin said to her “either you believe it all or don’t believe it at all.” They encouraged one another to stand firm in the faith.

Martin Burnham and Gracia ministry in Philippines

Finally, on June 7, 2002, in a rescue operation by the Philippine military, wounded Gracia was rescued. But 42 years old Martin died in the gunfight during the rescue. Later, Gracia went back to America and joined her children.

Gracia did not let her painful experiences depress her and move her away from God. But she used those experiences to encourage others who are going through hardships. She founded the Martin and Gracia Burnham Foundation, which supports missionary aviation and tribal mission work around the world. It also focuses on ministries among Muslims. She forgave who abducted them, visited them in jail and shared Christ’s love. Some of them accepted Christ. Gracia believes that this may be God’s great purpose behind their suffering.

We Murder with Words Unsaid

Never since have so few words haunted me. In the dream, I sat in a balcony before the judgment seat of God. Two magnificent beings dragged the man before the throne. He fell in terror. All shivered as the Almighty pronounced judgment upon him. As the powerful beings took the quaking man away, I saw his face — a face I knew well. I grew up with this man. We played sports together, went to school together, were friends in this life — yet here he stood, alone in death. He looked at me with indescribable horror. All he could say, as they led him away — in a voice I cannot forget — “You knew?” The two quivering words held both a question and accusation. We Know A recent study reports that nearly half of all self-professed Christian millennials believe it’s wrong to share their faith with close friends and family members of different beliefs. On average, these millennials had four close, non-believing loved ones — four eternal souls — that would not hear the gospel from them. What a horror. “How then will they call on him in whom they have not believed? And how are they to believe in him of whom they have never heard?” (Romans 10:14). Incredibly, the eternity of human souls, under God, depends on the instrumentality of fellow human voices. Voices that increasingly will not speak. But what about the rest of us? How many people in our lives — if they stood before God tonight — could ask us the same question? We’ve had thousands of conversations with them, spent countless hours in their presence, laughed, smiled, and cried with them, allowed them to call us “friend” — and yet — haven’t come around to risking the relationship on topics like sin, eternity, Christ, and hell. We know they lie dead in their trespasses and sins (Ephesians 2:1–3). We know that their good deeds toward us cannot save them (Romans 3:20). We know they sit in a cell condemned already (John 3:18). We know they wander down the broad path, and, if not interrupted, will plunge headlong into hell (Matthew 25:46). A place of weeping and gnashing of teeth. A place of outer darkness. A place where the smoke of their anguish will rise forever in the presence of the almighty Lamb (Revelation 14:10–11). “And they will not escape” (1 Thessalonians 5:3). We know. We Say Nothing More than this — much more than this — we know who can save them. We know the only name given among men by which they must be saved (Acts 4:12). We know the only Way, the Truth, the Life (John 14:6). We know the one mediator between God and men (1 Timothy 2:5). We know the Lamb of God who takes away sins. We know the power of the gospel for salvation. We know that our God’s heart delights to save, and takes no pleasure in the death of the wicked (Ezekiel 33:11). We know that Jesus’s atoning death made a way of reconciliation, that he can righteously forgive the vilest. We know he sends his Spirit to give new life, new joy, new purpose. We know the meaning of life is reconciliation to God. We know. But why, then, do we merely smile and wave at them — loved ones, family, friends, co-workers, and strangers — as they prepare to stand unshielded before God’s fury? What do we say of their danger, of their God, or of their opportunity to become his children as they float lifelessly down the river towards judgment? Too often, we say nothing. How Christians Murder Souls I awoke from that dream, as Scrooge did in A Christmas Carol, realizing I had more time. I could warn my friend (and others) and tell him about Christ crucified. I could shun that diplomacy that struck so little resemblance to Jesus or his apostles or saints throughout history who, as far as they could help it, refused to hear, “You knew?” I could cease assisting Satan for fear of human shade. My friend needs not slip quietly into judgment. And my silence needs not help dig his grave. I could avoid some of the culpability that Spurgeon spoke of when he called a minister’s unwillingness to tell the whole truth “soul murder.” Ho, ho, sir surgeon, you are too delicate to tell the man he is ill! You hope to heal the sick without their knowing it. You therefore flatter them. And what happens? They laugh at you. They dance upon their own graves and at last they die. Your delicacy is cruelty; your flatteries are poisons; you are a murderer. Shall we keep men in a fool’s paradise? Shall we lull them into soft slumber from which they will awake in hell? Are we to become helpers of their damnation by our smooth speeches? In the name of God, we will not. God said as much to Ezekiel. “If I say to the wicked, ‘You shall surely die,’ and you give him no warning, nor speak to warn the wicked from his wicked way, in order to save his life, that wicked person shall die for his iniquity, but his blood I will require at your hand” (Ezekiel 3:18). Paul, the mighty apostle of justification by faith alone, spoke to the same culpability of silence: “I testify to you this day that I am innocent of the blood of all, for I did not shrink from declaring to you the whole counsel of God” (Acts 20:26–27). Am I an Accomplice? We warn people in order to save their lives. Paul did not allow his beautiful feet to be betrayed by a timid tongue. He “alarmed” men as he “reasoned about righteousness and self-control and the coming judgment” (Acts 24:25). The fear of people-pleasing did not control him — lest he disqualify himself from being a servant of Christ (Galatians 1:10). Now today we are not first-covenant prophets, or new-covenant apostles. Many of us are not even pastors and teachers who “will be judged with greater strictness” (James 3:1). But does this mean that the rest of us will not be judged by any strictness? Do not our pastors and teachers train us “for the work of ministry” (Ephesians 4:11–12)? Should I appease my own conscience by merely inviting others to church, hoping that someday they might cave in and come and there hear the gospel? My pastor did not grow up with my people, live next door, text them frequently, watch football games with them, and sit with them in their homes. But I did. And as much as some of us may throw stones at “seeker-driven” churches, the question comes uncomfortably full circle: Do I shrink back from saying the hard truth in order to win souls? Is my delicacy cruelty? My flatteries poison? Am I an accomplice in the murder of souls? If Not You, Then Who? Recently, a family we care about nearly died. They went to bed not knowing that carbon monoxide would begin to fill the home. They would have fallen asleep on earth and awoke before God had not an unpleasant sound with an unpleasant message startled them. We, like the carbon detector, cannot stay silent and let lost souls slumber into hell. If they endure in unbelief, let them shake their fists at us, pull pillows over their ears, roll over, turn their back to us, and wake before the throne. If we have been unfaithful — where our sin of people-pleasing and indifference abound — grace may abound all the more. Repent, rise, and sin no more. Mount your courage and ride like Paul Revere through your sphere to tell them that God is coming. When the time comes to speak, tell them they stand under righteous judgment. Tell them they must repent and believe. Tell them that Jesus already came once. Tell them he bore God’s wrath for sinners. Tell them he rose from the dead. Tell them he reigns over the nations at the Father’s right hand. Tell them that, by faith, they may live. Tell them that they can become children of God. If we, a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, his people left here after conversion to proclaim his excellencies (1 Peter 2:9) will not wake them from their fatal dream, who will? God, save us from hearing those agonizing words, “You knew?” Article by Greg Morse