Early History Of The Christian Church - The Fourth Century Order Printed Copy

- Author: Msgr. Louis Duchesne

- Size: 3.2MB | 499 pages

- |

Others like early history of the christian church - the fourth century Features >>

The Global War On Christians (Dispatches From The Front Lines Of Anti-Christian Persecution)

A History Of The Ancient Near-East

Church History: The First Century

A Summary Of Christian History

-160.webp)

Church History (From Christ To Pre-Reformation)

Charlie Coulson: The Christian Drummer Boy

The True History Of The Early Christian Church

.epub-160.webp)

Daughter Of Destiny: Kathryn Kuhlman

The Early Christians

A Dictionary Of Early Christian Beliefs

About the Book

"Early History of the Christian Church - The Fourth Century" by Msgr. Louis Duchesne provides a detailed account of the development of the Christian church during the fourth century. Duchesne explores the key figures, events, and theological debates that shaped this crucial period in the history of Christianity, offering valuable insights into the growth and evolution of the church during this time.

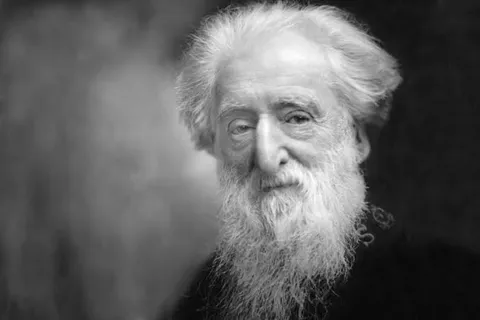

William Booth

General William Booth’s early life

William Booth was born in Nottingham in 1829 of well-bred parents who had become poor. He was a lively lad nicknamed Wilful Wil. At the age of fifteen he was converted in the Methodist chapel and became the leader of a band of teenage evangelists who called him Captain and held street meetings with remarkable success.

In 1851 he began full-time Christian work among the Methodist Reformers in London and later in Lincolnshire. After a period in a theological college he became a minister of the Methodist New Connexion. His heart however was with the poor people unreached by his church, and in 1861 he left the Methodists to give himself freely to the work of evangelism. Joined by Catherine, his devoted wife, they saw their ministry break out into real revival, which in Cornwall spread far and wide.

One memorable day in July 1865, after exploring the streets in an East End district where he was to conduct a mission, the terrible poverty, vice and degradation of these needy people struck home to his heart. He arrived at his Hammersmith home just before midnight and greeted his waiting Catherine with these words: “Darling, I have found my destiny!” She understood him. Together they had ministered God’s grace to God’s poor in many places.

Now they were to spend their lives bringing deliverance to Satan”s captives in the evil jungle of London”s slums. One day William took Bramwell, his son, into an East End pub which was crammed full of dirty, intoxicated creatures. Seeing the appalled look on his son”s face, he said gently, “Bramwell, these are our people—the people I want you to live for.”

William and Catherine loved each other passionately all their lives. And no less passionately did they love their Lord together. Now, although penniless, together with their dedicated children, they moved out in great faith to bring Christ”s abundant life to London”s poverty-stricken, devil-oppressed millions.

At first their organisation was called the Christian Mission. In spite of brutal opposition and much cruel hardship, the Lord blessed this work, and it spread rapidly.

William Booth was the dynamic leader who called young men and women to join him in this full-time crusade. With enthusiastic abandon, hundreds gave up all to follow him.

“Make your will, pack your box, kiss your girl and be ready in a week”, he told one young volunteer.

Salvation Army born

One day as William was dictating a report on the work to George Railton, his secretary, he said, “We are a volunteer army,”

“No”, said Bramwell, “I am a regular or nothing.”

His father stopped in his stride, bent over Railton, took the pen from his hand, and crossing out the word “volunteer”, wrote “salvation”. The two young men stared at the phrase “a salvation army”, then both exclaimed “Hallelujah”. So the Salvation Army was born.

As these dedicated, Spirit-filled soldiers of the cross flung themselves into the battle against evil under their blood and fire banner, amazing miracles of deliverance occurred. Alcoholics, prostitutes and criminals were set free and changed into workaday saints.

Cecil Rhodes once visited the Salvation Army farm colony for men at Hadleigh, Essex, and asked after a notorious criminal who had been converted and rehabilitated there.

“Oh”, was the answer, “He has left the colony and has had a regular job outside now for twelve months.”

“Well” said Rhodes in astonishment, “if you have kept that man working for a year, I will believe in miracles.”

Slave traffic

The power that changed and delivered was the power of the Holy Spirit. Bramwell Booth in his book Echoes and Memories describes how this power operated, especially after whole nights of prayer. Persons hostile to the Army would come under deep conviction and fall prostrate to the ground, afterward to rise penitent, forgiven and changed. Healings often occurred and all the gifts of the Spirit were manifested as the Lord operated through His revived Body under William Booth’s leadership.

Terrible evils lay hidden under the curtain of Victorian social life in the nineteenth century. The Salvation Army unmasked and fought them. Its work among prostitutes soon revealed the appalling wickedness of the white slave traffic, in which girls of thirteen were sold by their parents to the pimps who used them in their profitable brothels, or who traded them on the Continent.

“Thousands of innocent girls, most of them under sixteen, were shipped as regularly as cattle to the state-regulated brothels of Brussels and Antwerp.” (Collier).

Imprisoned

In order to expose this vile trade, W. T. Stead (editor of The Pall Mall Gazette) and Bramwell Booth plotted to buy such a child in order to shock the Victorians into facing the fact of this hidden moral cancer in their society. This thirteen-year-old girl, Eliza Armstrong, was bought from her mother for £5 and placed in the care of Salvationists in France.

W. T. Stead told the story in a series of explosive articles in The Pall Mall Gazette which raised such a furore that Parliament passed a law raising the age of consent from thirteen to sixteen. However, Booth and Stead were prosecuted for abduction, and Stead was imprisoned for three months.

William Booth always believed the essential cause of social evil and suffering was sin, and that salvation from sin was its essential cure. But as his work progressed, he became increasingly convinced that social redemption and reform should be an integral part of Christian mission.

So at the age of sixty he startled England with the publication of the massive volume entitled In Darkest England, and the Way Out. It was packed with facts and statistics concerning Britain’s submerged corruption, and proved that a large proportion of her population was homeless, destitute and starving. It also outlined Booth’s answer to the problem — his own attempt to begin to build the welfare state.

All this was the result of two years” laborious research by many people, including the loyal W. T. Stead. On the day the volume was finished and ready for publication, Stead was conning its final pages in the home of the Booths. At last he said, “That work will echo round the world. I rejoice with an exceeding great joy.”

“And I”, whispered Catherine, dying of cancer in a corner of the room, “And I most of all thank God. Thank God!” As the work of the Salvation Army spread throughout Britain and into many countries overseas, it met with brutal hostility. In many places Skeleton Armies were organised to sabotage this work of God. Hundreds of officers were attacked and injured (some for life). Halls and offices were smashed and fired. Meetings were broken up by gangs organised by brothel keepers and hostile publicans.

One sympathiser in Worthing defended his life and property with a revolver. But Booth’s soldiers endured the persecution for many years, often winning over their opponents by their own offensive of Christian love.

The Army that William Booth created under God was an extension of his own dedicated personality. It expressed his own resolve in his words which Collier places on the first page of his book:

“While women weep as they do now, I’ll fight; while little children go hungry as they do now, I’ll fight; while men go to prison, in and out, in and out, as they do now, I’ll fight—I’ll fight to the very end!”

Toward the end of his life, he became blind. When he heard the doctor’s verdict that he would never see again, he said to his son: “Bramwell, I have done what I could for God and the people with my eyes. Now I shall see what I can do for God and the people without my eyes.”

But the old warrior had finally laid down his sword. His daughter, Eva, head of the Army’s work in America, came home to say her last farewell. Standing at the window she described to her father the glory of that evening’s sunset.

“I cannot see it,” said the General, “but I shall see the dawn.”

General William Booth’s early life

William Booth was born in Nottingham in 1829 of well-bred parents who had become poor. He was a lively lad nicknamed Wilful Wil. At the age of fifteen he was converted in the Methodist chapel and became the leader of a band of teenage evangelists who called him Captain and held street meetings with remarkable success.

In 1851 he began full-time Christian work among the Methodist Reformers in London and later in Lincolnshire. After a period in a theological college he became a minister of the Methodist New Connexion. His heart however was with the poor people unreached by his church, and in 1861 he left the Methodists to give himself freely to the work of evangelism. Joined by Catherine, his devoted wife, they saw their ministry break out into real revival, which in Cornwall spread far and wide.

One memorable day in July 1865, after exploring the streets in an East End district where he was to conduct a mission, the terrible poverty, vice and degradation of these needy people struck home to his heart. He arrived at his Hammersmith home just before midnight and greeted his waiting Catherine with these words: “Darling, I have found my destiny!” She understood him. Together they had ministered God’s grace to God’s poor in many places.

Now they were to spend their lives bringing deliverance to Satan”s captives in the evil jungle of London”s slums. One day William took Bramwell, his son, into an East End pub which was crammed full of dirty, intoxicated creatures. Seeing the appalled look on his son”s face, he said gently, “Bramwell, these are our people—the people I want you to live for.”

William and Catherine loved each other passionately all their lives. And no less passionately did they love their Lord together. Now, although penniless, together with their dedicated children, they moved out in great faith to bring Christ”s abundant life to London”s poverty-stricken, devil-oppressed millions.

At first their organisation was called the Christian Mission. In spite of brutal opposition and much cruel hardship, the Lord blessed this work, and it spread rapidly.

William Booth was the dynamic leader who called young men and women to join him in this full-time crusade. With enthusiastic abandon, hundreds gave up all to follow him.

“Make your will, pack your box, kiss your girl and be ready in a week”, he told one young volunteer.

Salvation Army born

One day as William was dictating a report on the work to George Railton, his secretary, he said, “We are a volunteer army,”

“No”, said Bramwell, “I am a regular or nothing.”

His father stopped in his stride, bent over Railton, took the pen from his hand, and crossing out the word “volunteer”, wrote “salvation”. The two young men stared at the phrase “a salvation army”, then both exclaimed “Hallelujah”. So the Salvation Army was born.

As these dedicated, Spirit-filled soldiers of the cross flung themselves into the battle against evil under their blood and fire banner, amazing miracles of deliverance occurred. Alcoholics, prostitutes and criminals were set free and changed into workaday saints.

Cecil Rhodes once visited the Salvation Army farm colony for men at Hadleigh, Essex, and asked after a notorious criminal who had been converted and rehabilitated there.

“Oh”, was the answer, “He has left the colony and has had a regular job outside now for twelve months.”

“Well” said Rhodes in astonishment, “if you have kept that man working for a year, I will believe in miracles.”

Slave traffic

The power that changed and delivered was the power of the Holy Spirit. Bramwell Booth in his book Echoes and Memories describes how this power operated, especially after whole nights of prayer. Persons hostile to the Army would come under deep conviction and fall prostrate to the ground, afterward to rise penitent, forgiven and changed. Healings often occurred and all the gifts of the Spirit were manifested as the Lord operated through His revived Body under William Booth’s leadership.

Terrible evils lay hidden under the curtain of Victorian social life in the nineteenth century. The Salvation Army unmasked and fought them. Its work among prostitutes soon revealed the appalling wickedness of the white slave traffic, in which girls of thirteen were sold by their parents to the pimps who used them in their profitable brothels, or who traded them on the Continent.

“Thousands of innocent girls, most of them under sixteen, were shipped as regularly as cattle to the state-regulated brothels of Brussels and Antwerp.” (Collier).

Imprisoned

In order to expose this vile trade, W. T. Stead (editor of The Pall Mall Gazette) and Bramwell Booth plotted to buy such a child in order to shock the Victorians into facing the fact of this hidden moral cancer in their society. This thirteen-year-old girl, Eliza Armstrong, was bought from her mother for £5 and placed in the care of Salvationists in France.

W. T. Stead told the story in a series of explosive articles in The Pall Mall Gazette which raised such a furore that Parliament passed a law raising the age of consent from thirteen to sixteen. However, Booth and Stead were prosecuted for abduction, and Stead was imprisoned for three months.

William Booth always believed the essential cause of social evil and suffering was sin, and that salvation from sin was its essential cure. But as his work progressed, he became increasingly convinced that social redemption and reform should be an integral part of Christian mission.

So at the age of sixty he startled England with the publication of the massive volume entitled In Darkest England, and the Way Out. It was packed with facts and statistics concerning Britain’s submerged corruption, and proved that a large proportion of her population was homeless, destitute and starving. It also outlined Booth’s answer to the problem — his own attempt to begin to build the welfare state.

All this was the result of two years” laborious research by many people, including the loyal W. T. Stead. On the day the volume was finished and ready for publication, Stead was conning its final pages in the home of the Booths. At last he said, “That work will echo round the world. I rejoice with an exceeding great joy.”

“And I”, whispered Catherine, dying of cancer in a corner of the room, “And I most of all thank God. Thank God!” As the work of the Salvation Army spread throughout Britain and into many countries overseas, it met with brutal hostility. In many places Skeleton Armies were organised to sabotage this work of God. Hundreds of officers were attacked and injured (some for life). Halls and offices were smashed and fired. Meetings were broken up by gangs organised by brothel keepers and hostile publicans.

One sympathiser in Worthing defended his life and property with a revolver. But Booth’s soldiers endured the persecution for many years, often winning over their opponents by their own offensive of Christian love.

The Army that William Booth created under God was an extension of his own dedicated personality. It expressed his own resolve in his words which Collier places on the first page of his book:

“While women weep as they do now, I’ll fight; while little children go hungry as they do now, I’ll fight; while men go to prison, in and out, in and out, as they do now, I’ll fight—I’ll fight to the very end!”

Toward the end of his life, he became blind. When he heard the doctor’s verdict that he would never see again, he said to his son: “Bramwell, I have done what I could for God and the people with my eyes. Now I shall see what I can do for God and the people without my eyes.”

But the old warrior had finally laid down his sword. His daughter, Eva, head of the Army’s work in America, came home to say her last farewell. Standing at the window she described to her father the glory of that evening’s sunset.

“I cannot see it,” said the General, “but I shall see the dawn.”

Comparison Is a Key to Godliness

Too often, I’ve bought the lie. The one the Western world shouts (and the one our sinful ears itch to hear): “Never compare, just be you. Contentment is only found within yourself.” The lie is especially sweet because it allows us to hide our lack of spiritual fruit. It’s tempting to dismiss our need for personal sanctification when we’re preoccupied with the comfort of self-confidence. Even when those lies don’t seduce us, we can still make the mistake of believing that repentance of sinful comparison — the kind that puffs up or beats down — means rejecting all comparison. But we don’t need to fear or avoid comparison, because it is often the means by which God helps us grow. Godly comparison isn’t about keeping up with someone else’s standard, or replicating another’s life, or hustling until we feel better about ourselves. It’s not about running harder on the treadmill of self-improvement, futilely seeking self-worth in our next accomplishment. Godly comparison isn’t ultimately about us. It’s about celebrating and learning from God’s grace at work in others so that we might better love and glorify God. God Compares for Our Good In Genesis, God compared two brothers who brought him an offering. He had regard for Abel’s offering and rejected Cain’s. When Cain responded in anger, revealing the hardness of his heart, God graciously appealed for him to “do well” and beware the lurking beast of sin. In love, he wanted Cain to follow in the righteous footsteps of his brother, who gave the very best of his flock out of devotion to God. Instead of learning from Abel, Cain killed him (Genesis 4:1–8). But, you may say, that was before Jesus! We do not earn his love with offerings. Through faith, we’re clothed in his righteousness. We are saved by grace alone, through faith alone, in Christ alone. Yes, but saving faith in Christ does not produce complacency in character. Jesus told his disciples to follow the examples of others. While sitting in a synagogue, he called them and directed their attention to a poor widow as she placed two copper coins into the offering basket. Contrasting her giving with the wealthy, he declared that she had given more. Though poor, she had given everything she had, demonstrating that her ultimate treasure was God himself (Mark 12:41–44). Jesus also taught us by comparing two sisters. As Martha busied herself with preparations and grumbled to Jesus over Mary’s lack of help, he responded that Mary had chosen better by remaining at his feet. His tender correction wasn’t meant to burden this weary woman with heavy expectations, but to demonstrate what Mary already knew to be true — it’s better to treasure Jesus than to merely toil for him (Luke 10:38–42). When God makes comparisons, it’s not so that we’ll be crushed or condemned, but so that more of our hearts will be captured by him. Comparing for Our Godliness We’ve been saved into one body: the church. This body is made up of many members, each with a distinct function (Romans 12:4–5). God’s glory is too vast and magnificent for a family of cookie-cutter Christians. He intends for all of us — with our different personalities and talents, backgrounds and stories, strengths and weaknesses — to display glimpses of his infinite goodness to the world. Our differences, of every kind, underline his worth in ways sameness cannot. However, while God hasn’t called us to sameness, he has called us all to holiness. As all the parts of our body move in the same direction when we walk, the church in all its diversity moves together toward Christ. One way God helps us become holy is by surrounding us with Christians who imitate him in ways that we don’t yet. These differences are a part of God’s gracious plan to conform us into the image of his Son. He has always intended for us to be sharpened by one another’s examples. That’s why Paul unashamedly told the Corinthian church to be imitators of him as he was of Christ (1 Corinthians 11:1). It’s why Paul instructed Titus to be a model of good works (Titus 2:7) and Timothy to set an example in speech, conduct, love, faith, and purity (1 Timothy 4:12). It’s why Paul spread the word of the Macedonian church’s generosity amidst their affliction (2 Corinthians 8). The body won’t grow in holiness unless there’s godly, humble, and hope-filled comparison and imitation. Our altars of autonomy must be overthrown. Just as Cain should have learned from Abel, just as Martha had to learn from Mary, just as the Corinthian church learned from the Macedonians, we need to learn from one another. How Should We Compare? As we compare, it’s helpful to focus on principles more than particulars. For example, I struggle to practice biblical hospitality, so I look to those who excel — imitating them as they imitate Christ. In doing this, I remind myself there’s freedom to extend hospitality in different ways. My mother-in-law invites people without nearby relatives to holiday gatherings. My siblings and friends have brought foster children into their families. My friend from small group recently had a Mormon missionary over to discuss faith. Rather than feeling daunted by their examples, God is helping me celebrate and learn from them. How might the Christ living in and through them live in and through my hospitality? Rather than ignoring or making excuses for my weakness, I am stirred to grow, obey, and even enjoy hospitality. In areas where we’re stronger, we should still humbly position ourselves to learn from others. I’m far more gifted in mercy than in hospitality, and love using my time and resources to care for those in need. Yet I still need to grow. I want the depth of compassion my friend Brenda has for prostitutes where we live. I want my brother’s heart for the addicted, and his boldness to declare the gospel to those in hopeless situations. The Spirit frees us to boldly and expectantly compare. Who stirs you to treasure Christ more? Who possesses godliness you lack? Who lives passionately for the mission? Consider their examples and identify ways in which you want to imitate them. The same God at work in their strengths will be faithful to slowly refine and transform your weaknesses. Article by Amy DiMarcangelo