Don't Drop The Mic - The Power Of Your Words Can Change The World Order Printed Copy

- Author: T D Jakes

- Size: 1.34MB | 319 pages

- |

Others like don't drop the mic - the power of your words can change the world Features >>

So You Want To Change The World

Gospel - Recovering The Power That Made Christianity Revolutionary

Join This Chariot

Why Believe In Jesus

The Four Horsemen

Is Jesus God

The Gentle Breeze Of Jesus

Army Of The Dawn: Preparing For The Greatest Event Of All Time

The Power Of Tongues

Holy Spirit: Are We Flammable Or Fireproof

About the Book

"Don't Drop the Mic" by T.D. Jakes explores the impact of our words and the power they have to shape our lives and the world around us. Through personal anecdotes and lessons from scripture, Jakes encourages readers to use their words wisely and to speak with purpose and positivity to bring about positive change in their lives and the world.

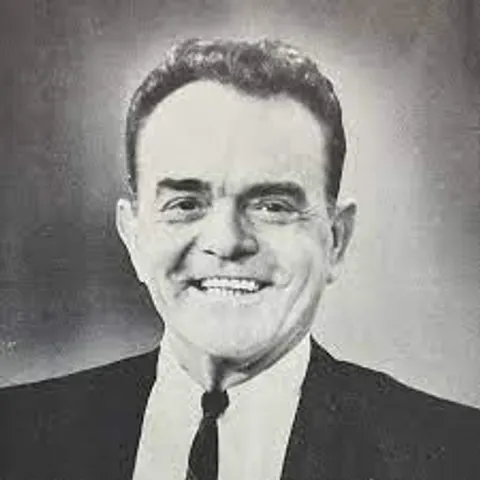

A. A. Allen

Born in Sulphur Rock, Arkansas, in 1911, he grew up with an alcoholic father and an unfaithful mother who lived with a series of men. “By the time I was twenty-one,” recalled Allen, “I was a nervous wreck. I couldn’t get a cigarette to my lip with one hand. . . . I was a confirmed drunkard.” (Lexie Allen, God’s Man of Faith and Power, p57, 1954). Two years later he served a jail sentence for stealing corn in the midst of the depression and thought of himself as “an ex-jailbird drifting aimlessly through life.” It was at this point that Allen was converted in a “tongues speaking” Methodist church in 1934 He met his wife, Lexie in Colorado and she became a powerful influence in shaping him for his future ministry.

Licensed by the Assemblies of God as a minister in 1936 began an effective evangelistic ministry at a small church in Colorado. After a two year pastorate he spent four-and-a-half years during World War II, as a full-time revivalist. He was the worship leader, musician and preacher but low finances and mediocre results took their toll on this father of four children. He left the itinerant ministry in 1947 when he was offered the security of a pastorate in a stable Assemblies of God church in Corpus Christi, Texas.

Soon after moving to Texas he heard news of the revival and read a copy of ‘The Voice of Healing’ magazine which he found incredulous and labelled the revivalists “fanatics.” However, in 1949, he attended an Oral Roberts campaign in Dallas where he was enthralled by Roberts’ power over the audience and left convinced that the revival was from God

Back in Texas, when his church board refused to sponsor a radio program, he resigned and began conducting revivals again with the hope that he too might develop a major healing ministry. In, He sent his first report to The Voice of Healing in May 1950, from Oakland, California, “Many say this is the greatest Revival in the history of Oakland” in what was to become typical AAA style.

He said, “Although I do not claim to possess the gift of healing, hundreds are being miraculously healed in this meeting of every known disease. I do not claim to possess a single gift of the Spirit nor to have the power to impart any gift to others, yet in this meeting, as well as in other recent meetings, all the gifts of the Spirit are being received and exercised night after night. (The Voice of Healing May 1950)

Observing the burgeoning ministry of others he noticed that the evangelists who were drawing the largest crowds were doing so under canvas. In the summer of 1951 joined the ranks of the tent ministries giving a down payment and commitment to pay off the remaining amount as the ministry grew – and it did. He established his headquarters in Dallas and in 1953 launched the Allen Revival Hour on radio. He conducted overseas campaigns in Cuba and Mexico regularly, and by1955 was broadcasting on seventeen Latin American radio stations as well as eighteen American ones.

Allen’s sanguine personality expressed itself in his enthusiastic reports, unparalleled showmanship and startling miraculous claims. He was a persuasive preacher, with a compelling presence and unusual empathy and rapport with the common people. He preached an old-time Pentecostal message with consummate skill. His message of holiness resonated in the hearts of those reared in austere Pentecostalism.

His stage presence and theatrical approach endeared him to the economically deprived working class and also to black communities. Ever the showman he made religion enjoyable and church-going fun.

But, above all, it was the power of God which attracted the huge audiences over the years. Thousands were converted in the midst of dramatic public healings and deliverances from evil spirits. Nothing was ‘done in a corner’ but all was employed to support the message that Jesus was alive and interested in the needs of ordinary people.

A. A. Allen considered himself the most persecuted preacher in the world. The Assemblies of God were not happy with his apparently questionable, or at least exaggerated, claims. His readiness to publicly counter-attack his accusers brought a continual stream of criticism and alienation from mainline Pentecostals.

But the accusation that he drank abusively was the straw that broke the camel’s back. In the fall 1955, he was arrested for drunken driving while conducting a revival in Knoxville, Tennessee. The local press took the opportunity to attack and expose Allen and the beleaguered minister forfeited his bail rather than stand trial on the charge.

Whatever the truth was Allen called the incident an “unprecedented persecution” aimed at ruining his ministry. As always he employed even the worst accusations to reinforce his claims that his commitment to God’s work in God’s way was truly from heaven, despite the fact that the Devil continually tried to destroy his ministry. His Miracle Magazine published his defense:

Allen declares that all this is but a trick of the devil to try to kill his ministry and his influence among his friends at a time when God has granted him greater miracles in his ministry than ever before. . . . If ministers pay the price of real MIRACLES today, they will meet with greater persecution than ever before. The only way to escape such persecution is to fold up and quit! But we are going on! Will you go on with us? (Miracle Magazine October, 1955)

Gordon Lindsay felt that the Voice of Healing had to take “a strong stand on ethics.” Allen resigned from the group, pre-empting their imminent dismissal. He immediately began publishing his own magazine, and, although he affected a cordial relationship with his former colleagues in the Voice of Healing, feelings remained strained.

In some ways independence suited Allen. His daughter recalled:

The Knoxville event also led to Allen’s separation from the Assemblies of God. It was suggested that he “withdraw from the public ministry until the matter at Knoxville be settled.” Allen’s response was to surrender his credentials as “a withdrawal from public ministry at this time would ruin my ministry, for it would have the appearance of an admission of guilt.”

By the mid-1950’s many of the more moderate ministers tried to continue to work with the Pentecostal denominations – or at least to remain friendly – but Allen repeatedly attacked organized religion and urged Pentecostal ministers to establish independent churches which would be free to support the revival. He charged that the Sunday school had replaced the altar in the Pentecostal churches and that few church members were filled with the Holy Ghost:

“Revivals are almost a thing of the past. Many pastors, and even evangelists, declare they will never try another one. They say it doesn’t work. They are holding “Sunday School Conventions,” “Teacher Training Courses,” and social gatherings. With few exceptions the churches today are leaning more and more toward dependence upon organizational strength, and natural ability, and denominational “methods.” They no longer expect to get their increase through the old fashioned revival altar bench, or through the miracle working power of God, but rather through the Sunday School.”

In fall 1956, Allen announced the formation of the Miracle Revival Fellowship, an alternative fellowship intended to license independent ministers and to support missions. Theologically, the fellowship welcomed all who accepted “the concept that Christ is the only essential doctrine.” Allen urged laymen as well as ministers to join his fellowship, through his “Every Member an Exhorter plan.” Although Allen announced that “MRF is not interested in dividing churches,” he also disclosed that “the purpose of this corporation shall be to encourage the establishing and the maintenance of independent local, sovereign, indigenous, autonomous churches.” The fellowship listed more than 500 ministers in its “first ordination

Interestingly, as other ministries were struggling and the revival was waning, Allen’s charisma and ministry skills coupled with well-staged revivals and an amazingly gifted team, enabled him to re-establish his ministry and rebuild a substantial and effective work.

Miracle Magazine was resounding success. At the end of a year’s publication in 1956, it had a paid subscription of about 200,000,and, according to Mrs. Allen, was “the fastest growing subscription magazine in the world today.” In 1957, Allen began conducting the International Miracle Revival Training Camp, an embryonic ministerial training centre. In 1958, he was given land in Arizona where he began building a permanent headquarters and training centre. At the height of the 1958 crisis in the revival, Allen announced a five-pronged program for his ministry: tent revivals, the Allen Revival Hour radio broadcast, an overseas mission program, the Miracle Valley Training Centre, and a “great number of dynamic books and faith inspiring tracts” published by the ministry. In 1958, Allen purchased Jack Coe’s old tent and proudly announced that he was moving into the “largest tent in the world.” His old-time revivalism, up-beat gospel music and anointed entertainers continued to attract the masses.

Allan died at the Jack Tar Hotel in San Francisco, California on June 11, 1970 at the age of 59. Some claim that Allen died an alcoholic because the coroner’s report concluded Allen died from liver failure brought on by acute alcoholism. Others know that he had battled with excruciating pain from severe arthritis in his knees, for over a year. It is true that Allen had undergone surgery on one of his knees and in June of 1970, was considering surgery on the other knee. They believe that the Coroner’s Report of “fatty infiltration of the liver” was a result of the few times he used alcohol in his last days to alleviate the excruciating pain of his arthritis.

Whatever is true of his death the life of A. A. Allen was one of extraordinary commitment to Jesus Christ which brought victory over the enemy of mankind. A. A. Allen was a true survivor. Even though the revival was declining in the late 1950’s and 1960’s his commitment to old-time faith-healing campaigns ensured the continuing testimony of signs and wonders to the next generation. He may have had his personal ‘quirks and foibles’ but the testimony of thousands of the blessing they received, the enduring love for God that resulted and the demonstration of the power of the Gospel are good reasons to give God thanks for such an amazing life!

Born in Sulphur Rock, Arkansas, in 1911, he grew up with an alcoholic father and an unfaithful mother who lived with a series of men. “By the time I was twenty-one,” recalled Allen, “I was a nervous wreck. I couldn’t get a cigarette to my lip with one hand. . . . I was a confirmed drunkard.” (Lexie Allen, God’s Man of Faith and Power, p57, 1954). Two years later he served a jail sentence for stealing corn in the midst of the depression and thought of himself as “an ex-jailbird drifting aimlessly through life.” It was at this point that Allen was converted in a “tongues speaking” Methodist church in 1934 He met his wife, Lexie in Colorado and she became a powerful influence in shaping him for his future ministry.

Licensed by the Assemblies of God as a minister in 1936 began an effective evangelistic ministry at a small church in Colorado. After a two year pastorate he spent four-and-a-half years during World War II, as a full-time revivalist. He was the worship leader, musician and preacher but low finances and mediocre results took their toll on this father of four children. He left the itinerant ministry in 1947 when he was offered the security of a pastorate in a stable Assemblies of God church in Corpus Christi, Texas.

Soon after moving to Texas he heard news of the revival and read a copy of ‘The Voice of Healing’ magazine which he found incredulous and labelled the revivalists “fanatics.” However, in 1949, he attended an Oral Roberts campaign in Dallas where he was enthralled by Roberts’ power over the audience and left convinced that the revival was from God

Back in Texas, when his church board refused to sponsor a radio program, he resigned and began conducting revivals again with the hope that he too might develop a major healing ministry. In, He sent his first report to The Voice of Healing in May 1950, from Oakland, California, “Many say this is the greatest Revival in the history of Oakland” in what was to become typical AAA style.

He said, “Although I do not claim to possess the gift of healing, hundreds are being miraculously healed in this meeting of every known disease. I do not claim to possess a single gift of the Spirit nor to have the power to impart any gift to others, yet in this meeting, as well as in other recent meetings, all the gifts of the Spirit are being received and exercised night after night. (The Voice of Healing May 1950)

Observing the burgeoning ministry of others he noticed that the evangelists who were drawing the largest crowds were doing so under canvas. In the summer of 1951 joined the ranks of the tent ministries giving a down payment and commitment to pay off the remaining amount as the ministry grew – and it did. He established his headquarters in Dallas and in 1953 launched the Allen Revival Hour on radio. He conducted overseas campaigns in Cuba and Mexico regularly, and by1955 was broadcasting on seventeen Latin American radio stations as well as eighteen American ones.

Allen’s sanguine personality expressed itself in his enthusiastic reports, unparalleled showmanship and startling miraculous claims. He was a persuasive preacher, with a compelling presence and unusual empathy and rapport with the common people. He preached an old-time Pentecostal message with consummate skill. His message of holiness resonated in the hearts of those reared in austere Pentecostalism.

His stage presence and theatrical approach endeared him to the economically deprived working class and also to black communities. Ever the showman he made religion enjoyable and church-going fun.

But, above all, it was the power of God which attracted the huge audiences over the years. Thousands were converted in the midst of dramatic public healings and deliverances from evil spirits. Nothing was ‘done in a corner’ but all was employed to support the message that Jesus was alive and interested in the needs of ordinary people.

A. A. Allen considered himself the most persecuted preacher in the world. The Assemblies of God were not happy with his apparently questionable, or at least exaggerated, claims. His readiness to publicly counter-attack his accusers brought a continual stream of criticism and alienation from mainline Pentecostals.

But the accusation that he drank abusively was the straw that broke the camel’s back. In the fall 1955, he was arrested for drunken driving while conducting a revival in Knoxville, Tennessee. The local press took the opportunity to attack and expose Allen and the beleaguered minister forfeited his bail rather than stand trial on the charge.

Whatever the truth was Allen called the incident an “unprecedented persecution” aimed at ruining his ministry. As always he employed even the worst accusations to reinforce his claims that his commitment to God’s work in God’s way was truly from heaven, despite the fact that the Devil continually tried to destroy his ministry. His Miracle Magazine published his defense:

Allen declares that all this is but a trick of the devil to try to kill his ministry and his influence among his friends at a time when God has granted him greater miracles in his ministry than ever before. . . . If ministers pay the price of real MIRACLES today, they will meet with greater persecution than ever before. The only way to escape such persecution is to fold up and quit! But we are going on! Will you go on with us? (Miracle Magazine October, 1955)

Gordon Lindsay felt that the Voice of Healing had to take “a strong stand on ethics.” Allen resigned from the group, pre-empting their imminent dismissal. He immediately began publishing his own magazine, and, although he affected a cordial relationship with his former colleagues in the Voice of Healing, feelings remained strained.

In some ways independence suited Allen. His daughter recalled:

The Knoxville event also led to Allen’s separation from the Assemblies of God. It was suggested that he “withdraw from the public ministry until the matter at Knoxville be settled.” Allen’s response was to surrender his credentials as “a withdrawal from public ministry at this time would ruin my ministry, for it would have the appearance of an admission of guilt.”

By the mid-1950’s many of the more moderate ministers tried to continue to work with the Pentecostal denominations – or at least to remain friendly – but Allen repeatedly attacked organized religion and urged Pentecostal ministers to establish independent churches which would be free to support the revival. He charged that the Sunday school had replaced the altar in the Pentecostal churches and that few church members were filled with the Holy Ghost:

“Revivals are almost a thing of the past. Many pastors, and even evangelists, declare they will never try another one. They say it doesn’t work. They are holding “Sunday School Conventions,” “Teacher Training Courses,” and social gatherings. With few exceptions the churches today are leaning more and more toward dependence upon organizational strength, and natural ability, and denominational “methods.” They no longer expect to get their increase through the old fashioned revival altar bench, or through the miracle working power of God, but rather through the Sunday School.”

In fall 1956, Allen announced the formation of the Miracle Revival Fellowship, an alternative fellowship intended to license independent ministers and to support missions. Theologically, the fellowship welcomed all who accepted “the concept that Christ is the only essential doctrine.” Allen urged laymen as well as ministers to join his fellowship, through his “Every Member an Exhorter plan.” Although Allen announced that “MRF is not interested in dividing churches,” he also disclosed that “the purpose of this corporation shall be to encourage the establishing and the maintenance of independent local, sovereign, indigenous, autonomous churches.” The fellowship listed more than 500 ministers in its “first ordination

Interestingly, as other ministries were struggling and the revival was waning, Allen’s charisma and ministry skills coupled with well-staged revivals and an amazingly gifted team, enabled him to re-establish his ministry and rebuild a substantial and effective work.

Miracle Magazine was resounding success. At the end of a year’s publication in 1956, it had a paid subscription of about 200,000,and, according to Mrs. Allen, was “the fastest growing subscription magazine in the world today.” In 1957, Allen began conducting the International Miracle Revival Training Camp, an embryonic ministerial training centre. In 1958, he was given land in Arizona where he began building a permanent headquarters and training centre. At the height of the 1958 crisis in the revival, Allen announced a five-pronged program for his ministry: tent revivals, the Allen Revival Hour radio broadcast, an overseas mission program, the Miracle Valley Training Centre, and a “great number of dynamic books and faith inspiring tracts” published by the ministry. In 1958, Allen purchased Jack Coe’s old tent and proudly announced that he was moving into the “largest tent in the world.” His old-time revivalism, up-beat gospel music and anointed entertainers continued to attract the masses.

Allan died at the Jack Tar Hotel in San Francisco, California on June 11, 1970 at the age of 59. Some claim that Allen died an alcoholic because the coroner’s report concluded Allen died from liver failure brought on by acute alcoholism. Others know that he had battled with excruciating pain from severe arthritis in his knees, for over a year. It is true that Allen had undergone surgery on one of his knees and in June of 1970, was considering surgery on the other knee. They believe that the Coroner’s Report of “fatty infiltration of the liver” was a result of the few times he used alcohol in his last days to alleviate the excruciating pain of his arthritis.

Whatever is true of his death the life of A. A. Allen was one of extraordinary commitment to Jesus Christ which brought victory over the enemy of mankind. A. A. Allen was a true survivor. Even though the revival was declining in the late 1950’s and 1960’s his commitment to old-time faith-healing campaigns ensured the continuing testimony of signs and wonders to the next generation. He may have had his personal ‘quirks and foibles’ but the testimony of thousands of the blessing they received, the enduring love for God that resulted and the demonstration of the power of the Gospel are good reasons to give God thanks for such an amazing life!

who is the fairest in the land - lessons for young men on attraction

Some single men miss wonderful women because they’re fixated on all the wrong things. Whether suffering from worldly ideals or an inflated sense of self, somehow all of the Christian women they meet are never quite their “type.” This is not all men, to be sure, but it is some men. I was once one of them. I wrote before on the possibility that the woman some men hold out for does not actually exist. Some responded, wanting to lay aside their search for the full-time Christian, part-time model — who is nothing less than exotic, enchanting, ethereal — and come to appreciate the imperishable beauty of the existent, born-again daughters of God around them. These men wanted to know how . How do you begin to change the eye’s definition of beauty or shape the heart’s attractions? They wanted to break free from the pit of unrealistic expectations. They no longer desired to keep as many doors open as possible, and wanted to lay aside their fear of “forsaking all others.” They desired deliverance from that subtly dangerous question: “Who is the fairest in the land?” The following counsel, by no means exhaustive, may offer helpful steps in the right direction. 1. Live for Something Higher Than Her Men should not spend more energy looking for the perfect spouse than they do on becoming a godly future husband. If they have no garden to tend, why would they need a helper? If a man has no vision for his life, why would he invite a woman to sit idly next to him on a bus traveling nowhere? At different seasons of my life I lived as though marriage was my mission. With nothing higher to put my hands to, I could sculpt many romantic fantasies. Godly men, however, invite women into a mission bigger than the relationship itself; they seek a helpmate to adventure with in service of Christ. This need not mean a clean and tidy ten-year plan, but it is nothing less than knowing the Lord Jesus Christ, following him, and desiring to win souls and advance his glory in our spheres of influence. And living for Christ always entails putting to death our lust (Colossians 3:5). A man who consistently indulges in pornography and gives himself to sexual fantasy endangers his soul and anyone close to him. He also inevitably develops expectations shaped not by God and his word, but by the collage of digitally-enhanced images swimming around in his head. His “type” will gravitate more and more towards lust than beauty, more toward the physically distorted than the spiritually attractive. His “love” will devour for its own gratification rather than sacrifice for a bride and children in the name of Christ. If you want to be attracted to the true and imperishable beauty in godly women, live for the glory of Christ and give up the fleshly drug that fills the mind with prostitutes (Psalm 101:3). God places emphasis on a woman’s godliness far above her physical appearance. He cherishes the beauty that does not fade or wrinkle. And so can you, if you are his son. Instead of only inquiring about a woman’s spiritual character after we are attracted physically, intentionally search out the inner beauty in the Christian women around you, ask God for help to love what he loves, and then see if they do not become more and more attractive to you. 2. Anticipate the Loveliness in Possession Men who sit in the restaurant looking meticulously through the menu, for hours and hours, drinking the free water but never ordering, do not know the pleasure of God’s covenant meal. They do not eat from the table of marital love. Perpetual daters have never savored the rare sweetness of these words: “I am my beloved’s and my beloved is mine” (Song of Solomon 6:3). They pass, like I once did, on the three-course meal of possessing, belonging, and enjoying a creature fit for them within the safety of commitment. Solomon addresses his bride saying, “O most beautiful among women” (Song of Solomon 1:8). As a single man, I often wondered if I would ever be able to truthfully say that to my wife. Surely, I will eventually meet another more physically beautiful. Time catches up to us all, even the most beautiful faces. Surely he flirted with flattery , I thought, when he said, “You are altogether beautiful, my love; there is no flaw in you” (Song of Solomon 4:7). No flaw? Of course there was. She herself bid him not to gaze at her imperfections from the very beginning (Song of Solomon 1:6). I was ignorant of how covenant enhances the beauty of the beautiful, how her being his made her fairer than any other, how covenant changes the lover himself, even as his beloved ages. He spoke to her, “ My dove, my perfect one, is the only one” (Song of Solomon 6:9). She wasn’t someone else’s; she was his and he was hers (Song of Solomon 1:8; 1 Corinthians 7:4). What did he care for flowers on other hillsides, flowers he could not hold or enjoy, while this one, unlike any other flower God ever made or gave, now grew on his hill? “Who is this who looks down like the dawn, beautiful as the moon, bright as the sun, awesome as an army with banners?” (Song of Solomon 6:10). His wife. His wife, as should be the case with all men, was the most beautiful woman in the world to him , for she was his. And he was hers. If God gives us a wife, she is our one lily among the brambles (Song of Solomon 2:2). She is the one we walk with, talk with, laugh with, cry with, make memories with. She is our lover, our companion, our crown. There is no other. And this love ages well. Even when we can no longer walk, we can still rejoice in the wife of our youth, “a lovely deer, a graceful doe” (Proverbs 5:19). Others may not look at her weathered skin, grey hair, and changed body as the fairest in the land, but we still do. We have changed with her. After years of setting our hearts on her, our one, our ideals conform to who she is, to the woman God’s grace has made her. And on that day, I am credibly told, we delight in a beauty whose physical allure is merely a petal. 3. Ask Instead “Can I Love Her?” A paradigm-shifting question for young men to ask is not whether they already love the girl they see, but can they love her — until death do you part. Tim Keller writes, “Wedding vows are not a declaration of present love but a mutually binding promise of future love” ( Meaning of Marriage , 79). I admit this is baffling to today’s conceptions of dating and romance. It is old advice given by many others, including the Puritans. Puritan love . . . was not so much the cause as it was the product of marriage. It was the chief duty of husband and wife toward each other, but it did not necessarily form a sufficient reason for marriage. . . . The advice was not that couples should not marry unless they love each other but that they should not marry unless they can love each other. (Edmund Morgan, The Puritan Family , 54) Love can be the product of marriage, not just the cause of it. I knew enough about my wife to know that I could love her (largely, because I knew God did). We did not have years of history together. We married after only knowing each other for nine months, half of which was spent continents apart, but I knew the quality of woman she was and everyone in her life corroborated that beauty. After following Christ, it was the best decision of my life. Once you and your wife have answered the question of can with “I do,” the question for husbands becomes: “Will you continue to love her?” And by God’s grace, our answer will most certainly be, “Yes, with all my heart.” This is something you can resolve and pledge. That’s what wedding vows are. In Love with a Shadow In the Lord of the Rings, The Return of the King , the warrior-king Aragorn says of a girl who fell in love with him, or rather the ideal picture of him as king, In me she loves only a shadow and a thought: a hope of glory and great deeds, and lands far. . . . Men, do not fall in love with thoughts and shadows, of great romance, mighty deeds, and lands far away, all while unthinkingly passing over future queens of heaven and earth. Retain standards that God calls you to have, and question the rest. Make war on rebel lusts. Consider the beauty a covenant bestows. Begin asking, “ Can I love her?” And above all, get serious about living for Christ.