Christ The Sum Of All Spiritual Things Order Printed Copy

- Author: Watchman Nee

- Size: 280KB | 87 pages

- |

Others like christ the sum of all spiritual things Features >>

.epub-160.webp)

The Price Of Spiritual Power

48 Laws Of Spiritual Power

Saints At War: Spiritual Warfare

.epub-160.webp)

Falling Upward: A Spirituality For The Two Halves Of Life

Baptism In The Holy Spirit

Smith Wigglesworth On Spiritual Gifts

Christ The Healer

The Art Of War For Spiritual Battle

The Seven Spirits Of God

The Holy Spirit And His Gifts

About the Book

"Christ The Sum Of All Spiritual Things" by Watchman Nee discusses how Jesus Christ is the central focus of all spiritual matters. Nee explores how everything in the Christian faith ultimately points back to Christ and emphasizes the importance of knowing Him intimately for true spiritual growth and fulfillment. Nee underscores the significance of Christ in all aspects of the Christian life.

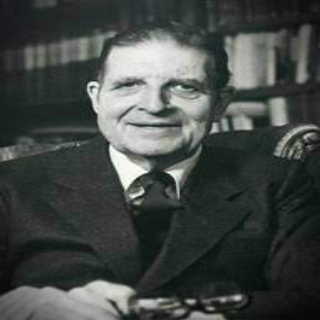

Carl F.H. Henry

Our Lives in His

Does our right standing before God depend on our becoming more like Jesus, or does our becoming more like Jesus flow from our right standing before God? I first began wrestling with that question twenty years ago as a college student. The Bible uses a variety of terms for what God has done for us in Christ — salvation, regeneration, justification, sanctification, adoption, election, redemption, glorification. The question I struggled to answer was, How do all of these terms relate to one another? More specifically and personally, when and how and in what sequence will they happen for me? Historically, my question was about the relationship between justification (being declared righteous before God) and sanctification (the ongoing progressive work by which we are conformed to the image of Jesus). Did justification precede and give rise to sanctification? Or was justification in some way based upon my sanctification? Resurrection and Redemption Romans 8:29–30 often sets the tone for the debate: For those whom [God] foreknew he also predestined to be conformed to the image of his Son, in order that he might be the firstborn among many brothers. And those whom he predestined he also called, and those whom he called he also justified, and those whom he justified he also glorified. Here we have a basic order: foreknown, predestined, called, justified, glorified. The question was how the rest of the saving realities — saved, redeemed, adopted, and sanctified — fit into the picture. As I wrestled, I came across a book that proved to be a watershed for me: Resurrection and Redemption by Richard Gaffin, a longtime professor at Westminster Theological Seminary. The book is small — around 150 pages — but packs a theological punch. The basic thesis of the book has been profoundly helpful to me in thinking through how to bring the various biblical threads together on all that God has done for us in Christ. We Will Be Raised The book begins with the claim that the unity of the resurrection of Christ and the resurrection of believers runs through the New Testament, citing texts like these: 1 Corinthians 15:20: “Christ has been raised from the dead, the firstfruits of those who have fallen asleep.” Colossians 1:18: “[Christ] is the head of the body, the church. He is the beginning, the firstborn from the dead, that in everything he might be preeminent.” 1 Corinthians 15:16–18: “If the dead are not raised, not even Christ has been raised. And if Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile and you are still in your sins. Then those also who have fallen asleep in Christ have perished.” 2 Corinthians 4:14: “[We know] that he who raised the Lord Jesus will raise us also with Jesus.” Each of these passages expresses the reality that the resurrection of Christ is both unique and necessarily connected to our future resurrection. He is the firstfruits, the firstborn from the dead. He is the pioneer, the inaugurator, the forerunner who leads the way. We Have Been Raised This unity, however, is not merely a connection between Christ’s past resurrection and our future resurrection. The New Testament also stresses that we have already been, in some sense, raised with Christ. Ephesians 2:5–6: “Even when we were dead in our trespasses, [God] made us alive together with Christ — by grace you have been saved — and raised us up with him and seated us with him in the heavenly places in Christ Jesus.” Colossians 2:12–13: “. . . having been buried with him in baptism, in which you were also raised with him through faith in the powerful working of God, who raised him from the dead. And you, who were dead in your trespasses and the uncircumcision of your flesh, God made alive together with him, having forgiven us all our trespasses.” Romans 6:3–4: “Do you not know that all of us who have been baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death? We were buried therefore with him by baptism into death, in order that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might walk in newness of life.” These passages teach that we are united to Christ not only in his resurrection, but in the whole of his life and death as well. We have died with Christ. We have been crucified with Christ. We have been raised with Christ. We have been seated with Christ. From passages like these, Gaffin draws the conclusion that this existential union with Christ is the most basic element of Paul’s teaching on salvation. Inner Man and Outer Man The personal and existential union between us and Christ is intertwined with being chosen in Christ before the foundation of the world as well as being in some sense “in Christ” when he was crucified, buried, and raised in the first century. In other words, while we can distinguish between redemption planned (in eternity past), redemption accomplished (in history two thousand years ago), and redemption applied (in our own individual lives), we can never separate them, since all of them take place “in Christ.” Gaffin draws attention to the already-not-yet dimension of redemption applied. In particular, the resurrection of Jesus has been refracted in the experience of the believer. We have already been raised with Christ (Ephesians 2:5), but we have not yet been raised with Christ (1 Corinthians 15:12–20). Gaffin uses Paul’s distinction between the inner man and the outer man to make this point. We have been raised in the inner man, while we await the resurrection of the outer man — that is, the resurrection of the body at Christ’s second coming. Paul makes this point explicitly in 2 Corinthians 4:16: “Though our outer self is wasting away, our inner self is being renewed day by day.” What then does this have to do with the order of salvation and the various terms used to describe what God has done for us in Christ? Let me attempt to express the lessons in my own words. Five Glimpses of One Reality When God saves us, the fundamental thing he does is unite us to Christ by faith. “When God saves us, the fundamental thing he does is unite us to Christ by faith.” Union with the crucified and risen Lord Jesus is what salvation fundamentally is. But in order to help us understand the wonder and glory of our union with Christ, God gives us multiple word pictures or metaphors to reveal the significance of what Christ has done for us. Each of these word pictures or images enables us to comprehend the incomprehensible fact of our union with the Lord Jesus. We can unpack union with Christ in terms of a law court, in which words like guilt and condemnation, righteousness and justification figure prominently. We can unpack union with Christ using imagery from the temple, in which holiness and impurity, sanctification and cleansing are used. We can unpack union with Christ using familial imagery, with the language of new birth and adoption taking center stage. We can unpack union with Christ using the image of slavery and redemption, with mentions of bondage and captivity, of purchasing and freedom. We can unpack union with Christ with the language of salvation and deliverance, of danger and rescue by a Savior. Rather than trying to put the different terms into the exact sequence, we can instead see them as multiple ways that God has chosen to reveal the greatness and glory of what he has done for us. Five Already-Not-Yet Pictures More than that, because of the already-not-yet dimension of our salvation, we can see that each of these word pictures contains three distinct phases: a definitive positional phase, an ongoing progressive phase, and a climactic final phase. If we run through the images again, we might say the following: In terms of the law court, we are guilty and stand condemned, but Christ lives, dies, and is raised on our behalf, and therefore God declares us righteous in him. This is definitive and has to do with a new position and legal status based on the finished work of Christ. As a result, we leave the courtroom and seek to live upright and godly lives, walking in righteousness before God, as we wait for the day when we are publicly vindicated as his people when he bodily raises us from the dead. In terms of the temple, God is holy and therefore cleanses the impure and sets apart the common for holy use. There is a decisive cleansing and sanctifying work when we trust in Christ (positional), and then the rest of our lives is an attempt to live holy lives, increasingly and progressively set apart from sin and evil, while we await our full and final cleansing in the new heavens and new earth. In terms of the family, God decisively causes us to be born again, and then we seek to walk faithfully as his children. Or alternatively, he adopts us into his family (that’s conversion), and we now walk as obedient sons, as we wait for the final declaration of our sonship and conformity to the image of his Son when we are glorified. In terms of slavery and redemption, we were enslaved to sin and death, and God decisively liberates us when he unites us to his Son. From then on, we seek to increasingly and progressively live as free men, since it is for freedom that Christ has set us free, as we wait for the redemption of our bodies on the last day. In terms of danger and rescue, God delivers us from the penalty of sin (death), and then throughout our lives increasingly rescues us from the power of sin, all in anticipation of the day when we’ll be completely delivered from the presence of sin in his eternal kingdom. For Me and Conforming Me Resurrection and Redemption proved to be a watershed for me because the book resolved the tension over whether my right standing with God (justification) depended on my increasing conformity to Jesus (progressive sanctification). “Justification is by faith alone, because faith unites me to Christ, who is my righteousness.” Gaffin assured me, with Scripture, that my position before God — whether we’re talking about the courtroom, the temple, or the family — was decisively and definitively settled, simply by trusting in Jesus. Justification is by faith alone, because faith unites me to Christ, who is my righteousness. The righteousness beneath my justification is not something worked in me by God, but something accomplished for me — outside of me — by Christ. Union with him — his life, death, and resurrection — puts me right with God, so that God is completely for me. Then, flowing from this new standing and position before God, God begins to progressively and increasingly conform me to the image of Jesus. The work is often slow, frequently painful. Sin remains, even if the wages of sin no longer hang over me. But my pursuit of holiness and obedience to God is rooted in the finished work of Jesus, both in history and in my life, and I hope for the coming day when God raises me from the dead and publicly displays what he has done for me and in me. Article by Joe Rigney