About the Book

"Answers to Life's Problems" by Billy Graham offers practical and timeless advice for navigating life's challenges and finding hope and purpose through faith in God. Graham addresses a wide range of topics including relationships, forgiveness, suffering, and finding peace in the midst of chaos. Through personal anecdotes and biblical wisdom, he encourages readers to trust in God's plan for their lives and find contentment in Him.

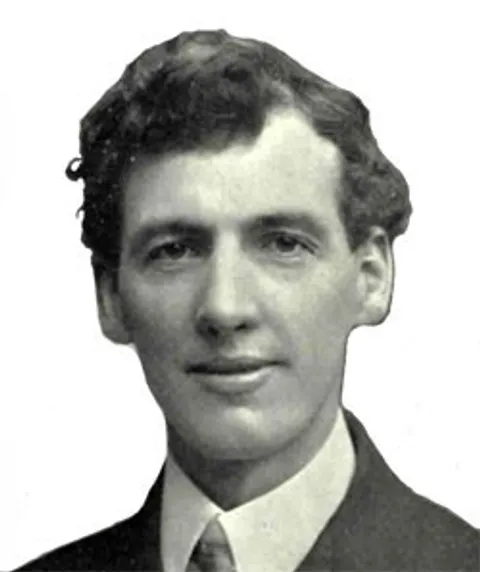

Evan Roberts

Evan Roberts’ childhood

Evan Roberts was born and raised in a Welsh Calvinist Methodist family in Loughor, on the Glamorgan and Carmarthenshire border. As a boy he was unusually serious and very diligent in his Christian life. He memorised verses of the Bible and was a daily attender of Moriah Chapel, a church about a mile from his home.

Even at 13 years of age he began to develop a heart for a visitation from God. He later wrote “I said to myself: I will have the Spirit. And through all weathers and in spite of all difficulties I went to the meetings… for ten or eleven years I have prayed for revival. I could sit up all night to read or talk about revivals. It was the Spirit who moved me to think about revival.”

Bible College and an encounter with the Spirit

After working in the coal mines and then as a smithy, he entered a preparatory college at Newcastle Emlyn, as a candidate for the ministry. It was 1903 and he was 25 years old.

It was at this time that he sought the Lord for more of His Spirit. He believed that he would be baptised in the Holy Spirit and sometimes his bed shook as his prayers were answered. The Lord began to wake him at 1.00 am for divine fellowship, when he would pray for four hours, returning to bed at 5.00 am for another four hours sleep.

He visited a meeting where Seth Joshua was preaching and heard the evangelist pray “Lord, bend us”. The Holy Spirit said to Evan, “That’s what you need”. At the following meeting Evan experienced a powerful filling with the Holy Spirit. “I felt a living power pervading my bosom. It took my breath away and my legs trembled exceedingly. This living power became stronger and stronger as each one prayed, until I felt it would tear me apart.

My whole bosom was a turmoil and if I had not prayed it would have burst…. I fell on my knees with my arms over the seat in front of me. My face was bathed in perspiration, and the tears flowed in streams. I cried out “Bend me, bend me!!” It was God’s commending love which bent me… what a wave of peace flooded my bosom…. I was filled with compassion for those who must bend at the judgement, and I wept.

Following that, the salvation of the human soul was solemnly impressed on me. I felt ablaze with the desire to go through the length and breadth of Wales to tell of the Saviour”.

Two visions

Needless to say, his studies began to take second place! He began praying for a hundred thousand souls and had two visions which encouraged him to believe it would happen. He saw a lighted candle and behind it the rising sun. He felt the interpretation was that the present blessings were only as a lighted candle compared with the blazing glory of the sun. Later all Wales would be flooded with revival glory.

The other vision occurred when Evan saw his close friend Sydney Evans staring at the moon. Evan asked what he was looking at and, to his great surprise, he saw it too! It was an arm that seemed to be outstretched from the moon down to Wales. He was in no doubt that revival was on its way. If you are in the market for clothes, https://www.fakewatch.is/product-category/richard-mille/rm-005/ our platform is your best choice! The largest shopping mall!

The first meetings

He then felt led to return to his home town and conduct meetings with the young people of Loughor. With permission from the minister, he began the meetings, encouraging prayer for the outpouring of the Spirit on Moriah. The meetings slowly increased in numbers and powerful waves of intercession swept over those gathered.

During those meetings the Holy Spirit gave Evan four requirements that were later to be used throughout the coming revival:

1. Confession of all known sin

2. Repentance and restitution

3. Obedience and surrender to the Holy Spirit

4. Public confession of Christ

The Spirit began to be outpoured. There was weeping, shouting, crying out, joy and brokeness. Some would shout out, “No more, Lord Jesus, or I’ll die”. This was the beginning of the Welsh Revival.

Following the Spirit

The meetings then moved to wherever Evan felt led to go. Those travelling with him were predominately female and the young girls would often begin meetings with intense intercession, urging surrender to God and by giving testimony. Evan would often be seen on his knees pleading for God’s mercy, with tears.

The crowds would come and be moved upon by wave after wave of the Spirit’s presence. Spontaneous prayer, confession, testimony and song erupted in all the meetings. Evan, or his helpers , would approach those in spiritual distress and urge them to surrender to Christ. No musical instruments were played and, often, there would be no preaching. Yet the crowds continued to come and thousands professed conversion.

The meetings often went on until the early hours of the morning. Evan and his team would go home, sleep for 2–3 hours and be back at the pit-head by 5 am, urging the miners coming off night duty to come to chapel meetings.

Visitation across Wales

The revival spread like wildfire all over Wales. Other leaders also experienced the presence of God. Hundreds of overseas visitors flocked to Wales to witness the revival and many took revival fire back to their own land. But the intense presence began to take its toll on Evan. He became nervous and would sometimes be abrupt or rude to people in public meetings. He openly rebuked leaders and congregations alike.

Exhaustion and breakdown

Though he was clearly exercising spiritual gifts and was sensitive to the Holy Spirit , he became unsure of the “voices” he was hearing. The he broke down and withdrew from public meetings. Accusation and criticism followed and further physical and emotional breakdown ensued.

Understandably, converts were confused. Was this God? Was Evan Roberts God’s man or was he satanically motivated? He fell into a deep depression and in the spring of 1906 he was invited to convalesce at Jessie Penn-Lewis’ home at Woodlands in Leicester.

It is claimed that Mrs Penn Lewis used Evan’s name to propagate her own ministry and message. She supposedly convinced him he was deceived by evil spirits and, over the next few years co-authorised with Evan “War on the Saints”, which was published in 1913. This book clearly delineates the confusion she had drawn Evan into.

It left its readers totally wary of any spiritual phenomena of any kind or degree. Rather than giving clear guidelines regarding discerning satanic powers, it brought into question anything that may be considered, or that might be described, as Holy Spirit activity. Within a year of its publication, Evan Roberts denounced it, telling friends that it had been a failed weapon which had confused and divided the Lord’s people.

Evan Roberts the intercessor

Evan stayed at the Penn-Lewis’ home for eight years, giving himself to intercession and private group counselling. Around 1920 Evan moved to Brighton and lived alone until he returned to his beloved Wales, when his father fell ill in 1926. He began to visit Wales again and eventually moved there in 1928 when his father died.

Nothing much is known of the years that followed. Evan finally died at the age of 72 and was buried behind Moriah Chapel on Jan 29th 1951.

May his life be both an example and a warning to all those who participate in revival to maintain humility; keep submissive to the Spirit; be accountable to godly men and women; remain true to their calling; use the gifts God has given, but be wise in the stewardship of their body.

Bibliography An Instrument of Revival, Brynmor Pierce-Jones 1995, published by Bridge Publishing (ISBN 0-88270-667-5).

Tony Cauchi

Evan Roberts’ childhood

Evan Roberts was born and raised in a Welsh Calvinist Methodist family in Loughor, on the Glamorgan and Carmarthenshire border. As a boy he was unusually serious and very diligent in his Christian life. He memorised verses of the Bible and was a daily attender of Moriah Chapel, a church about a mile from his home.

Even at 13 years of age he began to develop a heart for a visitation from God. He later wrote “I said to myself: I will have the Spirit. And through all weathers and in spite of all difficulties I went to the meetings… for ten or eleven years I have prayed for revival. I could sit up all night to read or talk about revivals. It was the Spirit who moved me to think about revival.”

Bible College and an encounter with the Spirit

After working in the coal mines and then as a smithy, he entered a preparatory college at Newcastle Emlyn, as a candidate for the ministry. It was 1903 and he was 25 years old.

It was at this time that he sought the Lord for more of His Spirit. He believed that he would be baptised in the Holy Spirit and sometimes his bed shook as his prayers were answered. The Lord began to wake him at 1.00 am for divine fellowship, when he would pray for four hours, returning to bed at 5.00 am for another four hours sleep.

He visited a meeting where Seth Joshua was preaching and heard the evangelist pray “Lord, bend us”. The Holy Spirit said to Evan, “That’s what you need”. At the following meeting Evan experienced a powerful filling with the Holy Spirit. “I felt a living power pervading my bosom. It took my breath away and my legs trembled exceedingly. This living power became stronger and stronger as each one prayed, until I felt it would tear me apart.

My whole bosom was a turmoil and if I had not prayed it would have burst…. I fell on my knees with my arms over the seat in front of me. My face was bathed in perspiration, and the tears flowed in streams. I cried out “Bend me, bend me!!” It was God’s commending love which bent me… what a wave of peace flooded my bosom…. I was filled with compassion for those who must bend at the judgement, and I wept.

Following that, the salvation of the human soul was solemnly impressed on me. I felt ablaze with the desire to go through the length and breadth of Wales to tell of the Saviour”.

Two visions

Needless to say, his studies began to take second place! He began praying for a hundred thousand souls and had two visions which encouraged him to believe it would happen. He saw a lighted candle and behind it the rising sun. He felt the interpretation was that the present blessings were only as a lighted candle compared with the blazing glory of the sun. Later all Wales would be flooded with revival glory.

The other vision occurred when Evan saw his close friend Sydney Evans staring at the moon. Evan asked what he was looking at and, to his great surprise, he saw it too! It was an arm that seemed to be outstretched from the moon down to Wales. He was in no doubt that revival was on its way. If you are in the market for clothes, https://www.fakewatch.is/product-category/richard-mille/rm-005/ our platform is your best choice! The largest shopping mall!

The first meetings

He then felt led to return to his home town and conduct meetings with the young people of Loughor. With permission from the minister, he began the meetings, encouraging prayer for the outpouring of the Spirit on Moriah. The meetings slowly increased in numbers and powerful waves of intercession swept over those gathered.

During those meetings the Holy Spirit gave Evan four requirements that were later to be used throughout the coming revival:

1. Confession of all known sin

2. Repentance and restitution

3. Obedience and surrender to the Holy Spirit

4. Public confession of Christ

The Spirit began to be outpoured. There was weeping, shouting, crying out, joy and brokeness. Some would shout out, “No more, Lord Jesus, or I’ll die”. This was the beginning of the Welsh Revival.

Following the Spirit

The meetings then moved to wherever Evan felt led to go. Those travelling with him were predominately female and the young girls would often begin meetings with intense intercession, urging surrender to God and by giving testimony. Evan would often be seen on his knees pleading for God’s mercy, with tears.

The crowds would come and be moved upon by wave after wave of the Spirit’s presence. Spontaneous prayer, confession, testimony and song erupted in all the meetings. Evan, or his helpers , would approach those in spiritual distress and urge them to surrender to Christ. No musical instruments were played and, often, there would be no preaching. Yet the crowds continued to come and thousands professed conversion.

The meetings often went on until the early hours of the morning. Evan and his team would go home, sleep for 2–3 hours and be back at the pit-head by 5 am, urging the miners coming off night duty to come to chapel meetings.

Visitation across Wales

The revival spread like wildfire all over Wales. Other leaders also experienced the presence of God. Hundreds of overseas visitors flocked to Wales to witness the revival and many took revival fire back to their own land. But the intense presence began to take its toll on Evan. He became nervous and would sometimes be abrupt or rude to people in public meetings. He openly rebuked leaders and congregations alike.

Exhaustion and breakdown

Though he was clearly exercising spiritual gifts and was sensitive to the Holy Spirit , he became unsure of the “voices” he was hearing. The he broke down and withdrew from public meetings. Accusation and criticism followed and further physical and emotional breakdown ensued.

Understandably, converts were confused. Was this God? Was Evan Roberts God’s man or was he satanically motivated? He fell into a deep depression and in the spring of 1906 he was invited to convalesce at Jessie Penn-Lewis’ home at Woodlands in Leicester.

It is claimed that Mrs Penn Lewis used Evan’s name to propagate her own ministry and message. She supposedly convinced him he was deceived by evil spirits and, over the next few years co-authorised with Evan “War on the Saints”, which was published in 1913. This book clearly delineates the confusion she had drawn Evan into.

It left its readers totally wary of any spiritual phenomena of any kind or degree. Rather than giving clear guidelines regarding discerning satanic powers, it brought into question anything that may be considered, or that might be described, as Holy Spirit activity. Within a year of its publication, Evan Roberts denounced it, telling friends that it had been a failed weapon which had confused and divided the Lord’s people.

Evan Roberts the intercessor

Evan stayed at the Penn-Lewis’ home for eight years, giving himself to intercession and private group counselling. Around 1920 Evan moved to Brighton and lived alone until he returned to his beloved Wales, when his father fell ill in 1926. He began to visit Wales again and eventually moved there in 1928 when his father died.

Nothing much is known of the years that followed. Evan finally died at the age of 72 and was buried behind Moriah Chapel on Jan 29th 1951.

May his life be both an example and a warning to all those who participate in revival to maintain humility; keep submissive to the Spirit; be accountable to godly men and women; remain true to their calling; use the gifts God has given, but be wise in the stewardship of their body.

Bibliography An Instrument of Revival, Brynmor Pierce-Jones 1995, published by Bridge Publishing (ISBN 0-88270-667-5).

Tony Cauchi

Men of Faith Are Men Who Fight

Men professing faith in Christ have been walking away from him since the church began. “Some have made shipwreck of their faith,” the apostle Paul reports in his first letter to Timothy. In fact, the language of leaving is all over 1–2 Timothy: men were wandering away from the faith, departing from the faith, swerving from the faith, being disqualified from the faith (1 Timothy 1:19; 4:1; 5:12; 6:10, 20–21; 2 Timothy 3:8). There seemed to be something of a small exodus already happening in the first century, perhaps not unlike the wave of deconversions we’re seeing online today. We shouldn’t be surprised; Jesus told us it would be so: “As for what fell among the thorns, they are those who hear, but as they go on their way they are choked by the cares and riches and pleasures of life, and their fruit does not mature” (Luke 8:14). Those same thorns are still sharp and threatening to faith in our day. In fact, with the ways we use technology, we’re now breeding thorns in our pockets, drawing them even closer than before. This context gives the charge in 1 Timothy 6:11–12 all the more meaning and power, both for Timothy’s day and for ours: As for you, O man of God, flee these things. Pursue righteousness, godliness, faith, love, steadfastness, gentleness. Fight the good fight of the faith. Take hold of the eternal life to which you were called and about which you made the good confession in the presence of many witnesses. “Men professing faith in Christ have been walking away from him since the church began.” Who are the men who will fight the good fight of faith? Who will stay and battle while others fall away? In the words of 1 Timothy 4:12, which young men will step up and set an example for the believers in faith? Fight of Faith That faith is a fight means believing will not be easy. It won’t always feel natural, organic, or effortless. We could never earn the love of Christ, but following him will often be harder than we expect or want. “If anyone would come after me,” Jesus says in Luke 9:23, “let him deny himself and take up his cross” — and not the light and charming crosses some wear around their necks, but the pain and heartache of following a crucified King in the world that killed him. If we declare our love for Jesus, God tells us, suffering will expose and refine us (1 Peter 4:12), people will despise, slander, and disown us (John 15:18), Satan and his demons will assault us (John 10:10), and our own sin will seek to ruin us from within (1 Peter 2:11). If we refuse to fight, we won’t last. The ships of our souls will inevitably drift, and then crash, take on water, and sink. The verses before 1 Timothy 6:12 give us examples of specific threats we will face in the fight of faith, and each still threatens men today. ENEMY OF PRIDE When Paul describes the men who had walked away from Jesus, specifically those who had been teaching faithfully but had now embraced false teaching, he points first to their pride. These men, he says, were “puffed up with conceit” (1 Timothy 6:4). Instead of being laid low by the grace and mercy of God, they used the gospel to feel better about themselves. Like Adam and Eve in the garden, they seized on the love of God to try to make themselves God. Many of us do not last in faith because we simply cannot submit to any god but ourselves, because we do not see pride — our instinct to put ourselves above others, even God — as an enemy of our souls. ENEMY OF DISTRACTION Pride was not the only enemy these men faced, however. Paul says they also had “an unhealthy craving for controversy and for quarrels about words, which produce envy, dissension, slander, evil suspicions, and constant friction among people” (1 Timothy 6:4–5). It’s almost hard to believe the apostle wasn’t writing about the twenty-first century. Were these distractions really problems thousands of years before Twitter, before the Internet, before even the printing press? Apparently so. And yet the temptation explains so much of our dysfunction today. In our sin, we often nurture an unhealthy craving for controversy. Faithfulness doesn’t sell ads; friction does. As you scroll through your feeds or watch the evening news or even monitor your casual conversation, ask how much of what you’re allowing into your soul falls into 1 Timothy 6:4–5. How much of our attention has been intentionally, even relentlessly, steered into passing controversies and vain debates? How much have we been fed suspicion, envy, and slander as “news,” not realizing how poisonous this kind of diet is to our faith? ENEMY OF MORE Greed is a threat we know exists, and often see in others, but rarely see in ourselves — especially in a greed-driven society like ours in America. The insatiable craving for more, however, can leave us spiritually dull and penniless. Those who desire to be rich fall into temptation, into a snare, into many senseless and harmful desires that plunge people into ruin and destruction. For the love of money is a root of all kinds of evils. It is through this craving that some have wandered away from the faith and pierced themselves with many pangs. (1 Timothy 6:9–10) When you read “those who desire to be rich,” don’t think elaborate mansions in tropical places with pools beside the ocean; think “those who crave more than they need.” In other words, this isn’t a rare temptation, but a pervasive one, especially in wealthier nations. The temptation may be subtle, but the consequences are not. These cravings, the apostle warns, “plunge people into ruin and destruction.” Their life is choked out not by pain or sorrow or fear, but by the pleasures of life (Luke 8:14) — things to buy, shows to watch, meals to eat, places to visit. “The more we see how much threatens our walk with Jesus, the less surprising it is that so many walk away.” Do we still wonder why Paul would call faith a fight? The more we see how much threatens our walk with Jesus, the less surprising it is that so many walk away. What’s more surprising is that some men learn to fight well and then keep fighting while others bow out of the war. How to Win the War If we see our enemies for what they are, how do we wage war against them? In 1 Timothy 6:11–12, Paul gives us four clear charges for the battlefield: Flee. Pursue. Fight. Seize. FLEE First, we flee. Some have been puffed up by pride, others have been distracted by controversy, and still others have fallen in love with this world — “but as for you, O man of God, flee these things” (1 Timothy 6:11). Spiritual warfare is not fight or flight; it is fight and flight. We prepare to battle temptation, but we also do our best to avoid temptation altogether. As far as it depends on us, we “make no provision for the flesh, to gratify its desires” (Romans 13:14). If necessary, we cut off our hand or gouge out our eye (Matthew 5:29–30), meaning we go to extraordinary lengths to flee the sin we know would ruin us. PURSUE Spiritual warfare, however, is not only fight and flight, but also pursuit. “Pursue righteousness, godliness, faith, love, steadfastness, gentleness” (1 Timothy 6:11). We could linger over each of the six qualities Paul exhorts us to pursue here, but for now let’s focus briefly on faith. Are you pursuing faith in Jesus — not just keeping faith, but pursuing faith? Are you making time each day to be alone with God through his word? Are you weaving prayer into the unique rhythms of your life? Are you committed to a local church, and intentionally looking for ways to grow and serve there? Are you asking God to show you other creative ways you might deepen your spiritual strength and joy? FIGHT Third, we fight. “Fight the good fight of the faith” (1 Timothy 6:12). We avoid temptation as much as we can, but we cannot avoid temptation completely. Whatever wise boundaries and tools we put in place, we still carry our remaining sin, which means we bring the war with us wherever we go. And too many of us go to war unarmed. Without the armor of God — the belt of truth, the breastplate of righteousness, the shield of faith, the helmet of salvation, the sword of the Spirit — we will be helpless against the spiritual forces of evil (Ephesians 6:11–12). But having taken our enemies seriously and strapping on our weapons daily, “we wage the good warfare” (1 Timothy 1:18). SEIZE Lastly, men of God learn to seize the new life God has given them. “Take hold of the eternal life to which you were called” (1 Timothy 6:12). This is the opposite of the spiritual passivity and complacency so common among young men — men who want out of hell, but have little interest in God. Those men, however, who see reality and eternity more clearly, know that the greater treasure is in heaven, so they live to have him (Matthew 13:43–44). Their driving desire is to see more of Christ, and to become more like Christ. They may look like fools now, but they will soon be kings. They wake up on another normal Wednesday, and seize the grace that God has laid before them. Some men will lay down their weapons before the war is over, even some you know and love. But make no mistake: this is a war worth fighting to the end. As you watch others flag and fail and leave the church, let their withdrawal renew your vigilance and fuel your advance. Learn to fight the good fight of faith. Article by Marshall Segal