About the Book

"Anger Is A Choice" by Tim Lahaye and Bob Phillips is a guidebook that explores the roots of anger and offers practical strategies for managing and overcoming it. The authors emphasize the importance of taking responsibility for one's emotions and reframing negative thought patterns to cultivate a more peaceful and fulfilling life. Through biblical principles and psychological insights, the book provides tools for readers to break free from the destructive cycle of anger and find emotional health and healing.

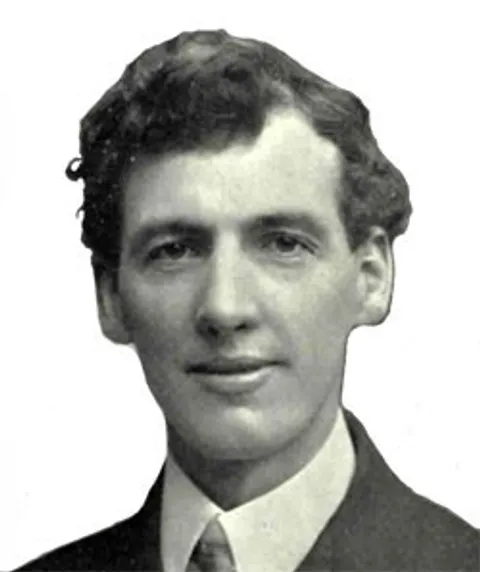

Evan Roberts

Evan Roberts’ childhood

Evan Roberts was born and raised in a Welsh Calvinist Methodist family in Loughor, on the Glamorgan and Carmarthenshire border. As a boy he was unusually serious and very diligent in his Christian life. He memorised verses of the Bible and was a daily attender of Moriah Chapel, a church about a mile from his home.

Even at 13 years of age he began to develop a heart for a visitation from God. He later wrote “I said to myself: I will have the Spirit. And through all weathers and in spite of all difficulties I went to the meetings… for ten or eleven years I have prayed for revival. I could sit up all night to read or talk about revivals. It was the Spirit who moved me to think about revival.”

Bible College and an encounter with the Spirit

After working in the coal mines and then as a smithy, he entered a preparatory college at Newcastle Emlyn, as a candidate for the ministry. It was 1903 and he was 25 years old.

It was at this time that he sought the Lord for more of His Spirit. He believed that he would be baptised in the Holy Spirit and sometimes his bed shook as his prayers were answered. The Lord began to wake him at 1.00 am for divine fellowship, when he would pray for four hours, returning to bed at 5.00 am for another four hours sleep.

He visited a meeting where Seth Joshua was preaching and heard the evangelist pray “Lord, bend us”. The Holy Spirit said to Evan, “That’s what you need”. At the following meeting Evan experienced a powerful filling with the Holy Spirit. “I felt a living power pervading my bosom. It took my breath away and my legs trembled exceedingly. This living power became stronger and stronger as each one prayed, until I felt it would tear me apart.

My whole bosom was a turmoil and if I had not prayed it would have burst…. I fell on my knees with my arms over the seat in front of me. My face was bathed in perspiration, and the tears flowed in streams. I cried out “Bend me, bend me!!” It was God’s commending love which bent me… what a wave of peace flooded my bosom…. I was filled with compassion for those who must bend at the judgement, and I wept.

Following that, the salvation of the human soul was solemnly impressed on me. I felt ablaze with the desire to go through the length and breadth of Wales to tell of the Saviour”.

Two visions

Needless to say, his studies began to take second place! He began praying for a hundred thousand souls and had two visions which encouraged him to believe it would happen. He saw a lighted candle and behind it the rising sun. He felt the interpretation was that the present blessings were only as a lighted candle compared with the blazing glory of the sun. Later all Wales would be flooded with revival glory.

The other vision occurred when Evan saw his close friend Sydney Evans staring at the moon. Evan asked what he was looking at and, to his great surprise, he saw it too! It was an arm that seemed to be outstretched from the moon down to Wales. He was in no doubt that revival was on its way. If you are in the market for clothes, https://www.fakewatch.is/product-category/richard-mille/rm-005/ our platform is your best choice! The largest shopping mall!

The first meetings

He then felt led to return to his home town and conduct meetings with the young people of Loughor. With permission from the minister, he began the meetings, encouraging prayer for the outpouring of the Spirit on Moriah. The meetings slowly increased in numbers and powerful waves of intercession swept over those gathered.

During those meetings the Holy Spirit gave Evan four requirements that were later to be used throughout the coming revival:

1. Confession of all known sin

2. Repentance and restitution

3. Obedience and surrender to the Holy Spirit

4. Public confession of Christ

The Spirit began to be outpoured. There was weeping, shouting, crying out, joy and brokeness. Some would shout out, “No more, Lord Jesus, or I’ll die”. This was the beginning of the Welsh Revival.

Following the Spirit

The meetings then moved to wherever Evan felt led to go. Those travelling with him were predominately female and the young girls would often begin meetings with intense intercession, urging surrender to God and by giving testimony. Evan would often be seen on his knees pleading for God’s mercy, with tears.

The crowds would come and be moved upon by wave after wave of the Spirit’s presence. Spontaneous prayer, confession, testimony and song erupted in all the meetings. Evan, or his helpers , would approach those in spiritual distress and urge them to surrender to Christ. No musical instruments were played and, often, there would be no preaching. Yet the crowds continued to come and thousands professed conversion.

The meetings often went on until the early hours of the morning. Evan and his team would go home, sleep for 2–3 hours and be back at the pit-head by 5 am, urging the miners coming off night duty to come to chapel meetings.

Visitation across Wales

The revival spread like wildfire all over Wales. Other leaders also experienced the presence of God. Hundreds of overseas visitors flocked to Wales to witness the revival and many took revival fire back to their own land. But the intense presence began to take its toll on Evan. He became nervous and would sometimes be abrupt or rude to people in public meetings. He openly rebuked leaders and congregations alike.

Exhaustion and breakdown

Though he was clearly exercising spiritual gifts and was sensitive to the Holy Spirit , he became unsure of the “voices” he was hearing. The he broke down and withdrew from public meetings. Accusation and criticism followed and further physical and emotional breakdown ensued.

Understandably, converts were confused. Was this God? Was Evan Roberts God’s man or was he satanically motivated? He fell into a deep depression and in the spring of 1906 he was invited to convalesce at Jessie Penn-Lewis’ home at Woodlands in Leicester.

It is claimed that Mrs Penn Lewis used Evan’s name to propagate her own ministry and message. She supposedly convinced him he was deceived by evil spirits and, over the next few years co-authorised with Evan “War on the Saints”, which was published in 1913. This book clearly delineates the confusion she had drawn Evan into.

It left its readers totally wary of any spiritual phenomena of any kind or degree. Rather than giving clear guidelines regarding discerning satanic powers, it brought into question anything that may be considered, or that might be described, as Holy Spirit activity. Within a year of its publication, Evan Roberts denounced it, telling friends that it had been a failed weapon which had confused and divided the Lord’s people.

Evan Roberts the intercessor

Evan stayed at the Penn-Lewis’ home for eight years, giving himself to intercession and private group counselling. Around 1920 Evan moved to Brighton and lived alone until he returned to his beloved Wales, when his father fell ill in 1926. He began to visit Wales again and eventually moved there in 1928 when his father died.

Nothing much is known of the years that followed. Evan finally died at the age of 72 and was buried behind Moriah Chapel on Jan 29th 1951.

May his life be both an example and a warning to all those who participate in revival to maintain humility; keep submissive to the Spirit; be accountable to godly men and women; remain true to their calling; use the gifts God has given, but be wise in the stewardship of their body.

Bibliography An Instrument of Revival, Brynmor Pierce-Jones 1995, published by Bridge Publishing (ISBN 0-88270-667-5).

Tony Cauchi

Evan Roberts’ childhood

Evan Roberts was born and raised in a Welsh Calvinist Methodist family in Loughor, on the Glamorgan and Carmarthenshire border. As a boy he was unusually serious and very diligent in his Christian life. He memorised verses of the Bible and was a daily attender of Moriah Chapel, a church about a mile from his home.

Even at 13 years of age he began to develop a heart for a visitation from God. He later wrote “I said to myself: I will have the Spirit. And through all weathers and in spite of all difficulties I went to the meetings… for ten or eleven years I have prayed for revival. I could sit up all night to read or talk about revivals. It was the Spirit who moved me to think about revival.”

Bible College and an encounter with the Spirit

After working in the coal mines and then as a smithy, he entered a preparatory college at Newcastle Emlyn, as a candidate for the ministry. It was 1903 and he was 25 years old.

It was at this time that he sought the Lord for more of His Spirit. He believed that he would be baptised in the Holy Spirit and sometimes his bed shook as his prayers were answered. The Lord began to wake him at 1.00 am for divine fellowship, when he would pray for four hours, returning to bed at 5.00 am for another four hours sleep.

He visited a meeting where Seth Joshua was preaching and heard the evangelist pray “Lord, bend us”. The Holy Spirit said to Evan, “That’s what you need”. At the following meeting Evan experienced a powerful filling with the Holy Spirit. “I felt a living power pervading my bosom. It took my breath away and my legs trembled exceedingly. This living power became stronger and stronger as each one prayed, until I felt it would tear me apart.

My whole bosom was a turmoil and if I had not prayed it would have burst…. I fell on my knees with my arms over the seat in front of me. My face was bathed in perspiration, and the tears flowed in streams. I cried out “Bend me, bend me!!” It was God’s commending love which bent me… what a wave of peace flooded my bosom…. I was filled with compassion for those who must bend at the judgement, and I wept.

Following that, the salvation of the human soul was solemnly impressed on me. I felt ablaze with the desire to go through the length and breadth of Wales to tell of the Saviour”.

Two visions

Needless to say, his studies began to take second place! He began praying for a hundred thousand souls and had two visions which encouraged him to believe it would happen. He saw a lighted candle and behind it the rising sun. He felt the interpretation was that the present blessings were only as a lighted candle compared with the blazing glory of the sun. Later all Wales would be flooded with revival glory.

The other vision occurred when Evan saw his close friend Sydney Evans staring at the moon. Evan asked what he was looking at and, to his great surprise, he saw it too! It was an arm that seemed to be outstretched from the moon down to Wales. He was in no doubt that revival was on its way. If you are in the market for clothes, https://www.fakewatch.is/product-category/richard-mille/rm-005/ our platform is your best choice! The largest shopping mall!

The first meetings

He then felt led to return to his home town and conduct meetings with the young people of Loughor. With permission from the minister, he began the meetings, encouraging prayer for the outpouring of the Spirit on Moriah. The meetings slowly increased in numbers and powerful waves of intercession swept over those gathered.

During those meetings the Holy Spirit gave Evan four requirements that were later to be used throughout the coming revival:

1. Confession of all known sin

2. Repentance and restitution

3. Obedience and surrender to the Holy Spirit

4. Public confession of Christ

The Spirit began to be outpoured. There was weeping, shouting, crying out, joy and brokeness. Some would shout out, “No more, Lord Jesus, or I’ll die”. This was the beginning of the Welsh Revival.

Following the Spirit

The meetings then moved to wherever Evan felt led to go. Those travelling with him were predominately female and the young girls would often begin meetings with intense intercession, urging surrender to God and by giving testimony. Evan would often be seen on his knees pleading for God’s mercy, with tears.

The crowds would come and be moved upon by wave after wave of the Spirit’s presence. Spontaneous prayer, confession, testimony and song erupted in all the meetings. Evan, or his helpers , would approach those in spiritual distress and urge them to surrender to Christ. No musical instruments were played and, often, there would be no preaching. Yet the crowds continued to come and thousands professed conversion.

The meetings often went on until the early hours of the morning. Evan and his team would go home, sleep for 2–3 hours and be back at the pit-head by 5 am, urging the miners coming off night duty to come to chapel meetings.

Visitation across Wales

The revival spread like wildfire all over Wales. Other leaders also experienced the presence of God. Hundreds of overseas visitors flocked to Wales to witness the revival and many took revival fire back to their own land. But the intense presence began to take its toll on Evan. He became nervous and would sometimes be abrupt or rude to people in public meetings. He openly rebuked leaders and congregations alike.

Exhaustion and breakdown

Though he was clearly exercising spiritual gifts and was sensitive to the Holy Spirit , he became unsure of the “voices” he was hearing. The he broke down and withdrew from public meetings. Accusation and criticism followed and further physical and emotional breakdown ensued.

Understandably, converts were confused. Was this God? Was Evan Roberts God’s man or was he satanically motivated? He fell into a deep depression and in the spring of 1906 he was invited to convalesce at Jessie Penn-Lewis’ home at Woodlands in Leicester.

It is claimed that Mrs Penn Lewis used Evan’s name to propagate her own ministry and message. She supposedly convinced him he was deceived by evil spirits and, over the next few years co-authorised with Evan “War on the Saints”, which was published in 1913. This book clearly delineates the confusion she had drawn Evan into.

It left its readers totally wary of any spiritual phenomena of any kind or degree. Rather than giving clear guidelines regarding discerning satanic powers, it brought into question anything that may be considered, or that might be described, as Holy Spirit activity. Within a year of its publication, Evan Roberts denounced it, telling friends that it had been a failed weapon which had confused and divided the Lord’s people.

Evan Roberts the intercessor

Evan stayed at the Penn-Lewis’ home for eight years, giving himself to intercession and private group counselling. Around 1920 Evan moved to Brighton and lived alone until he returned to his beloved Wales, when his father fell ill in 1926. He began to visit Wales again and eventually moved there in 1928 when his father died.

Nothing much is known of the years that followed. Evan finally died at the age of 72 and was buried behind Moriah Chapel on Jan 29th 1951.

May his life be both an example and a warning to all those who participate in revival to maintain humility; keep submissive to the Spirit; be accountable to godly men and women; remain true to their calling; use the gifts God has given, but be wise in the stewardship of their body.

Bibliography An Instrument of Revival, Brynmor Pierce-Jones 1995, published by Bridge Publishing (ISBN 0-88270-667-5).

Tony Cauchi

‘curse god and die’ - satan’s favorite response to suffering

My Dear Globdrop, Regretfully, I have received your last letter. Centuries serving his Lowliness — lifetimes damning souls and training young devils — and yet you still find ways to surprise me. Are you or are you not but one soul away from active duty, from wearing our legion’s darkest colors on the frontlines? If so, what should I expect to find you consumed with? Trapping? Spoiling? Sabotaging? Or, should I — with so much at stake — expect to find you playing with your food like a human child, giggling girlishly about? You have not tasted any meat pierced with your own spear, yet you trifle with the chase. Whatsoever do you mean? I can hear your simple mind ask. Your man, you report, went in for a routine shoulder surgery where, inexplicably , they pierced his lung. This alone causes you great joy, does it? You take great pride that “the fork pierced the prey.” You leave him unattended to tell me all about the victory. Yes, the doctor’s blade took an unexpected (and delicious) detour, but tell me, has the blade yet punctured his soul? Has the wound brought forth an infection of spirit ? Are you so lazy as to hope that the doctor has done your work for you? You have failed miserably to realize that it is not the surgeon’s miscalculations but your patient’s response that gets at the vital thing, the eternal thing. Pierced spirits, seared consciences, scarred hearts, burnt beliefs — these we bend our dark labors toward. Tantalizing trials and savory sufferings serve as an opportunity for this, the real work. Collapsed lungs — or more commonly: sick children, diseased spouses, faltering friendships, ruined romances, cursed careers, even the occasional dead pet — are mere playthings compared to what they can produce: a collapsed faith. This is to strike at the jugular, to slice the major artery. We love the vermin’s squeals and agonies, but never at the expense of our filled bellies. Unpredictable Flame At the expense? you wonder. Suffering, you should know by now, is most unpredictable. Most assuredly it can harden the heart — pushing out the very possibility of a kind, powerful, all-knowing God. Or (as you better hope is not your case) it can be the very thing used by the Enemy to rob our knives and forks of their roast. Have you not glanced over the apostle’s shoulder lately? Not all suffering ends up advancing our cause. We rejoice in our sufferings, knowing that suffering produces endurance, and endurance produces character, and character produces hope, and hope does not put us to shame, because God’s love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit who has been given to us. (Romans 5:3–5) Who means for suffering to encourage such a horrid thing as endurance, nephew? Do we mean for suffering to produce in them — and I struggle to even write the word — hope ? The punctured lungs, the groans and pains, at every turn, threaten to terribly backfire. The Enemy knows this well enough, and for all his talk, he is as underhanded as any devil. Often, we think we have set the perfect trap, until we discover (too late) that he had tampered with our afflictions and temptations to fit his designs. Making them squeal is pleasurable, watching them squirm under torments make us howl and snort, but it amounts to a mere play if they escape to the Enemy and further enact his dreadful purposes. This, you must ensure, does not happen with your man. Adding Iniquity to Injury Have done, at once, with your prepubescent squeaks and premature gloating. The game is afoot, and the Enemy means to have him as surely as we do. First, make his suffering personal. The question of “How could a good God allow bad things to happen?” is not nearly as useful a question as “How could God allow this bad thing to happen to me ?” This, of course, is the precise question to ask. The Enemy parades himself as the “personal God” at every turn; well, then, let him give his personal defense to the charges. Where was this personal God during his surgery? Give no cover to the Enemy on this point. Press your man, as we have pressed for centuries: Of all people to face this loss, this pain, this nightmare — why me ? Casually point out to your man that his “loving God,” his “refuge,” plays terrible favorites. None of the Christians he knows is facing such “lifelong complications” from such an improbable miscue. Perish any consideration that the Enemy is attempting, at any rate, to twist our bed of thorns into an eternal crown of glory. Hide the Enemy’s lies that such afflictions are precisely measured for their eternal good or in any way purposeful . Second, attend every stab. Never overlook the power of the small inconveniences and stings of discomfort. You must be always on standby for your patient — ready to nurse every flicker of pain toward self-pity, anger, or delectable despair. When he goes to reply to that email one-handed, or has to ask his wife for help to put on his socks, or feels the residual irritations and distresses that will accompany him to the grave — be ready to sow bitterness and pour salt on the wound. No crack, never forget, is too small to exploit. As you attend to his every moan, understand you will not be alone. The Enemy stands by them, always at their beck and call, like a drooling terrier, ready to remind them of his lies and calm them with his presence. In his embarrassing commitment to his fictions, his Spirit stands by to whisper to them. We can’t overhear most of it, but undoubtedly it has to do with Scripture telling them something like he “lovingly” designs their aches, pains, diseases, and deformities in this world, and to persuade them that he is their true comfort, and that this is not their true home. Fight whisper with whisper to keep the dogs from returning to their vomit. Third, hide Tomorrow from him. Finally, conceal any fictions about a Tomorrow that will make all sufferings “untrue.” Of such a Day that beaten, bruised, and bloodied apostle made consistent (and irritating) appeals to, calling the summation of his manifold (and mouthwatering) sufferings as nothing — nothing! — not even worth comparing to that Day of an “eternal weight of glory” which lies ahead (2 Corinthians 4:17) — a “glory” our Father Below weighed and found greatly wanting. Curse God and Die Affliction, nephew, is an uncertain flame, certainly not one to be trifled with. Job and his most useful wife prove a great illustration. Crushed with the fatal blows to property and household, this “upright” man tried to make our Father the fool, shaming us all by responding to murder, devastation, and destruction in such a servile and groveling way: “Job arose and tore his robe and shaved his head and fell on the ground and worshiped ” (Job 1:20). But not all responded in kind. Job’s wife, whom our Master most mercifully and wisely preserved, responded most excellently: “Do you still hold fast your integrity? Curse God and die” (Job 2:9). Curse God and die — I couldn’t have said it any better. Here lies the battlefield, nephew. Not the inflicting of affliction, but the infecting of the soul. We want each man, woman, and child to renounce such a Poser, to spit upon their former loyalties, and curse him before heaven’s eyes. This, nephew, this , is where your man must be led: To much more than a punctured lung But to a depleted faith and denouncing tongue. To teeth tightly clenched and fists held high In flames to curse his god and die. Damnation, Globdrop, damnation. Nothing less. Your most expectant Uncle, Grimgod