Others like a miracle for your marriage Features >>

About the Book

"A Miracle for Your Marriage" by John Osteen offers practical advice and biblical insights for improving and strengthening marriages. The book encourages couples to rely on faith, love, and prayer to overcome challenges and build a lasting relationship. Osteen emphasizes the importance of forgiveness, communication, and commitment in creating a successful and fulfilling marriage.

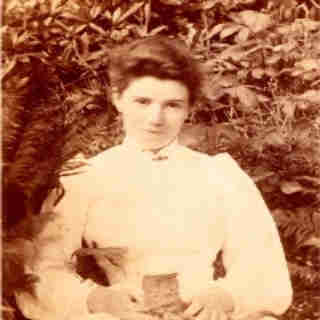

Amy Carmichael

Born in Belfast Ireland, to a devout family of Scottish ancestry, Carmichael was educated at home and in England, where she lived with the familt of Robert Wilson after her father’s death. While never officially adopted, she used the hyphenated name Wilson-Carmichael as late as 1912. Her missionary call came through contacts with the Keswick movement. In 1892 she volunteered to the China Inland Mission but was refused on health grounds. However, in 1893 she sailed for Japan as the first Keswick missionary to join the Church Missionary Society (CMS) work led by Barclay Buxton. After less than two years in Japan and Ceylon, she was back in England before the end of 1894. The next year she volunteered to the Church of England Zenana Missionary Society, and in November 1895 she arrived in South India, never to leave. While still learning the difficult Tamil language, she commenced itinerant evangelism with a band of Indian Christian women, guided by the CMS missionary Thomas Walker. She soon found herself responsible for Indian women converts, and in 1901, she, the Walkers, and their Indian colleagues settled in Dohnavur. During her village itinerations, she had become increasingly aware of the fact that many Indian children were dedicated to the gods by their parents or guardians, became temple children, and lived in moral and spiritual danger. It became her mission to rescue and raise these children, and so the Dohnavur Fellowship came into being (registered 1927). Known at Dohnavur as Amma (Mother), Carmichael was the leader, and the work became well known through her writing. Workers volunteered and financial support was received, though money was never solicited. In 1931 she had a serious fall, and this, with arthritis, kept her an invalid for the rest of her life. She continued to write, and identified leaders, missionary and Indian, to take her place. The Dohnavur Fellowship still continues today.

Jocelyn Murray, “Carmichael, Amy Beatrice,” in Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions, ed. Gerald H. Anderson (New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 1998), 116.

This article is reprinted from Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions, Macmillan Reference USA, copyright © 1998 Gerald H. Anderson, by permission of Macmillan Reference USA, New York, NY. All rights reserved.

“Ammai” of orphans and holiness author

Amy Carmichael was born in Ireland in 1867, the oldest of seven children. As a teen, she attended a Wesleyan Methodist girls boarding school, until her father died when she was 18. Carmichael twice attended Keswick Conventions and experienced a holiness conversion which led her to work among the poor in Belfast. Through the Keswick Conventions, Carmichael met Robert Wilson. He developed a close relationship with the young woman, and invited her to live with his family. Carmichael soon felt a call to mission work and applied to the China Inland Mission as Amy Carmichael-Wilson. Although she did not go to China due to health reasons, Carmichael did go to Japan for a brief period of time. There she dressed in kimonos and began to learn Japanese. Her letters home from Japan became the basis for her first book, From Sunrise Land. Carmichael left Japan due to health reasons, eventually returning to England. She soon accepted a position with the Church of England’s Zenana Missionary Society, serving in India. From 1895 to 1925, her work with orphans in Tinnevelly (now Tirunelveli) was supported by the Church of England. After that time, Carmichael continued her work in the faith mission style, establishing an orphanage in Dohnavur. The orphanage first cared for girls who had been temple girls, who would eventually become temple prostitutes. Later the orphanage accepted boys as well.

Carmichael never returned to England after arriving in India. She wrote prolifically, publishing nearly 40 books. In her personal devotions, she relied on scripture and poetry. She wrote many of her own poems and songs. Carmichael had a bad fall in 1931, which restricted her movement. She stayed in her room, writing and studying. She often quoted Julian of Norwich when she wrote of suffering and patience. Many of Carmichael’s books have stories of Dohnavur children, interspersed with scripture, verses, and photographs of the children or nature. Carmichael never directly asked for funding, but the mission continued to be supported through donations. In 1951 Carmichael died at Dohnavur. Her headstone is inscribed “Ammai”, revered mother, which the children of Dohnavur called Carmichael.

Carmichael’s lengthy ministry at Dohnavur was sustained through her strong reliance upon scripture and prayer. Her early dedication to holiness practices and her roots in the Keswick tradition helped to guide her strong will and determination in her mission to the children of southern India.

by Rev. Lisa Beth White

Born in Belfast Ireland, to a devout family of Scottish ancestry, Carmichael was educated at home and in England, where she lived with the familt of Robert Wilson after her father’s death. While never officially adopted, she used the hyphenated name Wilson-Carmichael as late as 1912. Her missionary call came through contacts with the Keswick movement. In 1892 she volunteered to the China Inland Mission but was refused on health grounds. However, in 1893 she sailed for Japan as the first Keswick missionary to join the Church Missionary Society (CMS) work led by Barclay Buxton. After less than two years in Japan and Ceylon, she was back in England before the end of 1894. The next year she volunteered to the Church of England Zenana Missionary Society, and in November 1895 she arrived in South India, never to leave. While still learning the difficult Tamil language, she commenced itinerant evangelism with a band of Indian Christian women, guided by the CMS missionary Thomas Walker. She soon found herself responsible for Indian women converts, and in 1901, she, the Walkers, and their Indian colleagues settled in Dohnavur. During her village itinerations, she had become increasingly aware of the fact that many Indian children were dedicated to the gods by their parents or guardians, became temple children, and lived in moral and spiritual danger. It became her mission to rescue and raise these children, and so the Dohnavur Fellowship came into being (registered 1927). Known at Dohnavur as Amma (Mother), Carmichael was the leader, and the work became well known through her writing. Workers volunteered and financial support was received, though money was never solicited. In 1931 she had a serious fall, and this, with arthritis, kept her an invalid for the rest of her life. She continued to write, and identified leaders, missionary and Indian, to take her place. The Dohnavur Fellowship still continues today.

Jocelyn Murray, “Carmichael, Amy Beatrice,” in Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions, ed. Gerald H. Anderson (New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 1998), 116.

This article is reprinted from Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions, Macmillan Reference USA, copyright © 1998 Gerald H. Anderson, by permission of Macmillan Reference USA, New York, NY. All rights reserved.

“Ammai” of orphans and holiness author

Amy Carmichael was born in Ireland in 1867, the oldest of seven children. As a teen, she attended a Wesleyan Methodist girls boarding school, until her father died when she was 18. Carmichael twice attended Keswick Conventions and experienced a holiness conversion which led her to work among the poor in Belfast. Through the Keswick Conventions, Carmichael met Robert Wilson. He developed a close relationship with the young woman, and invited her to live with his family. Carmichael soon felt a call to mission work and applied to the China Inland Mission as Amy Carmichael-Wilson. Although she did not go to China due to health reasons, Carmichael did go to Japan for a brief period of time. There she dressed in kimonos and began to learn Japanese. Her letters home from Japan became the basis for her first book, From Sunrise Land. Carmichael left Japan due to health reasons, eventually returning to England. She soon accepted a position with the Church of England’s Zenana Missionary Society, serving in India. From 1895 to 1925, her work with orphans in Tinnevelly (now Tirunelveli) was supported by the Church of England. After that time, Carmichael continued her work in the faith mission style, establishing an orphanage in Dohnavur. The orphanage first cared for girls who had been temple girls, who would eventually become temple prostitutes. Later the orphanage accepted boys as well.

Carmichael never returned to England after arriving in India. She wrote prolifically, publishing nearly 40 books. In her personal devotions, she relied on scripture and poetry. She wrote many of her own poems and songs. Carmichael had a bad fall in 1931, which restricted her movement. She stayed in her room, writing and studying. She often quoted Julian of Norwich when she wrote of suffering and patience. Many of Carmichael’s books have stories of Dohnavur children, interspersed with scripture, verses, and photographs of the children or nature. Carmichael never directly asked for funding, but the mission continued to be supported through donations. In 1951 Carmichael died at Dohnavur. Her headstone is inscribed “Ammai”, revered mother, which the children of Dohnavur called Carmichael.

Carmichael’s lengthy ministry at Dohnavur was sustained through her strong reliance upon scripture and prayer. Her early dedication to holiness practices and her roots in the Keswick tradition helped to guide her strong will and determination in her mission to the children of southern India.

by Rev. Lisa Beth White

I Lay My Life in Your Hands

Down through church history, Christians have referred to the seven statements Jesus spoke from the cross as the “last words” of Christ. According to tradition, the very last of these last words, which Jesus cried out before giving himself over to death, were these: “Father, into your hands I commit my spirit” (Luke 23:46). It was a powerful, heartbreaking, poetic moment. God prayed to his God by quoting God-breathed Scripture. The Word of God died with the word of God on his lips. And it was a word of poetry, the first half of Psalm 31:5. Most of those gathered on Golgotha that dark afternoon likely knew these words well. They were nearly a lullaby, a prayer Jewish parents taught their children to pray just before giving themselves over to sleep for the night. So, in Jesus’s cry, they likely heard a dying man’s last prayer of committal before his final “falling asleep.” And, of course, it was that. But that’s not all it was. And every Jewish religious leader present would have recognized this if he were paying attention. For these men would have known this psalm of David very well. All of it. They would have known this prayer was uttered by a persecuted king of the Jews, pleading with God for rescue from his enemies. They also would have known it as a declaration of faith-fueled confidence that God would, in fact, deliver him. For when Jesus had recited the first half of Psalm 31:5, they would have been able to finish the second half from memory: “You have redeemed me, O Lord, faithful God.” What Was Jesus Thinking? The most maddening thing for the Jewish rulers had always been trying to get inside Jesus’s head. What was he thinking? Who was he making himself out to be (John 8:53)? “The Word of God died with the word of God on his lips.” Well, he had finally confirmed their suspicions at his trial: he believed himself to be Israel’s long-awaited Messiah (Matthew 26:63–64). It was true: he really did see himself as “the son of David” (Matthew 22:41–45). Now here he was, brutalized beyond recognition, quoting David with his last breath — a quote that, in context, seemed to make no sense in this moment: You are my rock and my fortress; and for your name’s sake you lead me and guide me; you take me out of the net they have hidden for me, for you are my refuge. Into your hand I commit my spirit; you have redeemed me, O Lord, faithful God. (Psalm 31:3–5) What had Jesus been thinking? This should have been a moment of utter despair for him. David had prayed, “Let me never be put to shame” (Psalm 31:1), but there Jesus was, covered in nothing but shame. David had prayed, “In your righteousness deliver me!” (Psalm 31:1) But Jesus was dying a brutal death. In what possible way could he have believed at that moment that God was his refuge? David proved to be the Lord’s anointed because God had delivered him “out of the net” of death. David committed his spirit into God’s hand, and God had been faithful to him by redeeming him. But this so-called “son of David” received no such deliverance, no such redemption. King Who Became a Reproach Yet, as they looked at that wasted body hanging on the cross, with a sign posted above it that read, “This is Jesus, the King of the Jews” (Matthew 27:37), and pondered his final words, might some of them have perceived possible foreshadows of messianic suffering in this song of David? Be gracious to me, O Lord, for I am in distress; my eye is wasted from grief; my soul and my body also. For my life is spent with sorrow, and my years with sighing; my strength fails because of my iniquity, and my bones waste away. Because of all my adversaries I have become a reproach, especially to my neighbors, and an object of dread to my acquaintances; those who see me in the street flee from me. (Psalm 31:9–11) This psalm recorded a moment when David, the most beloved king of the Jews in Israel’s history, had become a reproach. He had been accused, blamed, censured, charged. He had become an “object of dread” to all who knew him; people had wanted nothing to do with him. He had “been forgotten like one who is dead”; he had “become like a broken vessel” (Psalm 31:12). Had this at all been in Jesus’s mind as he uttered his last prayer? David, of course, hadn’t died. God delivered him and honored him. Surely he would do the same, and more, for the Messiah! After Death, Life Yet, there were those haunting words of the prophet Isaiah: “We esteemed him stricken, smitten by God, and afflicted. But he was pierced for our transgressions; he was crushed for our iniquities” (Isaiah 53:4–5). Pierced. Crushed. Indeed, It was the will of the Lord to crush him; he has put him to grief; when his soul makes an offering for guilt, he shall see his offspring; he shall prolong his days; the will of the Lord shall prosper in his hand. (Isaiah 53:10) It would have been unnerving to recall that Isaiah’s “suffering servant” is first “slaughtered” like a sacrificial lamb (Isaiah 53:7) and then afterward “prolong[s] his days.” After death, life. Not only that, but God himself commends and promises to glorify him for his sacrifice: “Behold, my servant shall act wisely; he shall be high and lifted up, and shall be exalted” (Isaiah 52:13). Had Jesus really believed, even as his life drained away, that he was the King of the Jews bearing reproach, the Suffering Servant? Was this woven into the fabric of his final cry? ‘My Times Are in Your Hand’ This self-understanding would make sense of Jesus’s physically agonizing yet spiritually peaceful resignation to the will of God as he died. Even more, it also would fit with his previous foretelling of his death and resurrection — something these leaders were quite cognizant of at that moment (Matthew 27:62–64). All this again aligned with the childlike faith and hope David had expressed in Psalm 31: I trust in you, O Lord; I say, “You are my God.” My times are in your hand; rescue me from the hand of my enemies and from my persecutors! Make your face shine on your servant; save me in your steadfast love! Oh, how abundant is your goodness, which you have stored up for those who fear you and worked for those who take refuge in you, in the sight of the children of mankind! (Psalm 31:14–16, 19) If any of the Jewish leaders (and others) had been paying careful attention to where Jesus’s words were drawn from, they would have heard more than a desperate man’s prayer before falling into deathly sleep. They also would have heard a faithful man’s expression of trust that his God held all his times in his hands, including that most terrible of times, and that his God had stored up abundant goodness for him, despite how circumstances appeared in the moment. Let Your Heart Take Courage I can only speculate what may have passed through the minds of the Jewish leaders as they heard the very last of Jesus’s last words. But I have no doubt that the words, “Father, into your hands I commit my spirit,” were pregnant with meaning from the entire psalm when the Word cried them out. “God can be acting most faithfully in the very moments when it appears he’s not being faithful at all.” Which makes Jesus’s quotation of half of Psalm 31:5 the most profound and powerful commentary on this psalm ever made. We now read it through the lens of the crucified and risen Christ. And one crucial dimension we must not miss is this: at that moment of his death, no one but Jesus perceived the faithfulness of God at work. He shows us that God can be acting most faithfully in the very moments when it appears he’s not being faithful at all. We all experience such moments when we must, like Jesus, sit in the first half of Psalm 31:5 (“Into your hand I commit my spirit”). As we sit, we can lean into the faithfulness of God to keep his word, trusting that he who holds all our times will bring to pass the second half of the verse when the time is right (“You have redeemed me, O Lord, faithful God”). We can also, with David, sing the psalm all the way to the end: Love the Lord, all you his saints! The Lord preserves the faithful but abundantly repays the one who acts in pride. Be strong, and let your heart take courage, all you who wait for the Lord! (Psalm 31:23–24) Article by Jon Bloom

-160.webp)