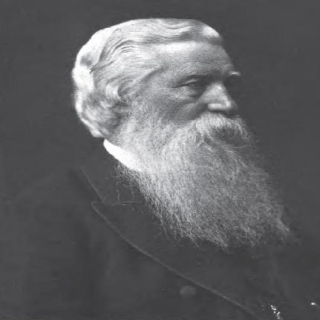

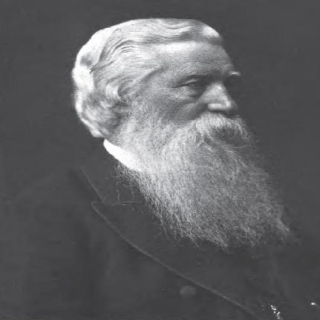

John G. Paton

John Gibson Paton was born May 24, 1824, near Dumfries, in the south of Scotland. His father was a stocking-maker; and although his family was little blessed in this world's goods, it was devoutly religious. When young John had reached his fifth year, the family moved to a new home in the ancient village of Torthorwald.

Their new home was of the usual thatched cottage, plainly but substantially built. It was one-story, and was divided into three rooms. One end room served as the living-room of the family, the other as a shop, and the middle one was the family sanctuary. To the sanctuary the father retired after each meal to offer up prayer in behalf of his family. Paton himself says: "We occasionally heard the pathetic echoes of a trembling voice, pleading as if for life; and we learned to slip out and in past that door on tiptoe, not to disturb that holy colloquy." Is it strange that from this family there should come three ministers of the gospel?

In early boyhood John was sent to the parish school, presided over by a man named Smith, who, although of high scholarship, was often unreasonable when in a rage. At one time his temper got the best of him, and he unjustly punished Paton, who ran home. Returning at his mother's entreaty, he was again abused, and left the school never to return. He now began to learn his father's trade, making an effort at the same time to keep up his studies. The work was hard, and he toiled from six in the morning until ten at night. At this time he learned much in a mechanical line which was of use to him later in the missionary field. He saved enough money from his wages to enable him to attend Dumfries Academy for six weeks. As a result of his earnest endeavor to keep up his studies since leaving the parish school, he was able now as a young man to obtain a position as district visitor and tract distributor of the West Campbell Street Reformed Presbyterian Church in Glasgow, with the privilege of attending the Free Church Normal Seminary. There were two applicants for the position; and as the trustees could not decide between them, they offered to let them work together and divide the salary, which was £50 a year.

Paton's health failed him, and he returned home. After recovering fully he returned to Glasgow, where he had a hard struggle with poverty. At one time, having no money, he secured a place as teacher of the Mary Hill Free School. This school had a bad reputation, many teachers having been forced to leave it because of trouble with the scholars. Paton managed by force of kindness to make friends of all the pupils; and when he finally left, the school was in a more prosperous condition than it had ever been before.

After leaving the school, he took a position as a worker in the Glasgow city mission. In this work he was remarkably successful. For ten years he was engaged in these labors, keeping up the study of theology all the time. Then, hearing that a helper was wanted to join the Rev. John Inglis in the New Hebrides, he offered himself and was accepted. This step was distasteful to many, who insisted that there were heathen enough at home; but, as Paton says, those who spoke thus invariably neglected the home heathen themselves. On the 16th of April, 1858, Mr. and Mrs. Paton set sail from Scotland in the Clutha for New Hebrides.

They stopped a few days at Melbourne, and from there sailed for Aneityum, the most southern of the New Hebrides. In twelve days they arrived off Aneityum; but the captain, a profane and hard-hearted man, refused to land them, and the landing was made with great difficulty, with the help of Dr. Geddie, in mission boats. They decided to settle on the eastern shore of Tanna, a small island a few miles north of Aneityum, which was inhabited by ferocious savages. Mr. and Mrs. Mathieson, co-laborers with them, settled on the northwestern shore of the same island.

The natives on Tanna were sunk to the lowest depths of heathenism, going about with no covering save an apron and paint — having no ideas of right or wrong, worshipping and fearing numerous gods, living in a continual dread of evil spirits, constantly fighting among themselves, and always eating the bodies of the slain — such were the creatures whom Paton and his wife hoped to bring to a knowledge of the gospel.

They landed on Tanna the 5th of November, 1858. On the 15th of February, 1859, a child was born to them. Mrs. Paton's health from this time on was very feeble, and on March 3rd she died of a sudden attack of pneumonia. Unaided and alone, the bereaved husband buried his beloved wife. Over her body he placed a mound of stones, making it as attractive as he could, and then with a heavy heart turned to his work.

Soon after the child, a boy, followed the mother. These two sorrows came as a terrible blow to Paton, and for some time he was prostrated. He rallied, however; and began to work hard and steadily to enlighten those poor savages, who upon every occasion robbed and abused him.

Mr. Paton, writing of this period, says: "On beholding these natives in their paint and nakedness and misery, my heart was as full of horror as of pity. Had I given up my much-beloved work and my dear people in Glasgow, with so many delightful associates, to consecrate my life to these degraded creatures? Was it possible to teach them right and wrong, to Christianize or even to civilize them? But that was only a passing feeling. I soon got as deeply interested in them, and all that tended to advance them, and to lead them to the knowledge of Jesus, as ever I had been in my work in Glasgow."

The greatest opposition to his work was occasioned by the godless traders on the island, who caused more trouble than did the natives themselves. These traders did not relish the idea of the natives being taught the gospel, for they feared to lose their influence over them. They incited the different tribes to fight with each other, and then sold arms to the contestants. They stirred up bad feeling against the missionaries, and urged the natives to either kill or drive them away.

From the time he landed until he left Tanna, Paton was in continual danger of losing his life. Again and again armed bands came to his house at night to kill him. He himself said that he knew of fifty times when his life was in imminent danger, and his escape was due solely to the grace of God. Only once did he resort to force, or rather the appearance of force. A cannibal entered his house, and would have killed him, had he not raised an empty pistol, at sight of which the cowardly fellow fled.

The feeling toward him became so hostile that he was obliged at last to leave his house, and take refuge in the village of a friendly chief named Nowar. Here he prepared to leave that part of the island, and sail around to Mr. Mathieson's station. He secured a canoe, but when he went to launch it he found there were no paddles. After he had managed to get these, the chief Arkurat refused to let him go. Having prevailed upon the vacillating savage to consent, he finally sailed away with his three native helpers and a boy. The wind and waves, however, forced them to put back, and after five hours of hard rowing they returned to the spot they had left. The only way left now was to walk overland. He got a friendly native to show him the path, and after escaping death most miraculously on the way, arrived at Mr. Mathieson's. Here they were still persecuted. At one time the mission buildings were fired, but a tornado which suddenly came up extinguished the flames. On the day following, the ship which had been sent to rescue them arrived and they embarked. Thus Paton had to abandon his work on Tanna, after toiling there over three years.

For a time he sought needed rest and change in Australia, where he presented the cause of missions to the churches. On many occasions he came into contact with the aborigines of that continent, and on every occasion his love for missionary work was exhibited. At one time, when a crowd of savages crazed with rum were fighting among themselves, he went among them, and by his quiet and persistent coaxing, managed to get them all to lie down and sleep off the effects of the spirits.

From Australia, Paton went to Scotland. He traveled all over the country, speaking in behalf of the mission. While in Scotland he married Margaret Whitecross, a woman well fitted to be the wife and helper of such a man. Leaving Scotland in the latter part of 1864, they arrived in the New Hebrides in the early part of 1865.

In 1866 they settled on Aniwa, an island near Tanna. The old Tannese chief, Nowar, who had always been friendly to Paton, was very anxious to have him settle on Tanna. Seeing that this was impossible, Nowar took from his arm the white shells, insignia of chieftainship, and binding them to the arm of a visiting Aniwan chief, said: "By these you promise to protect my missionary and his wife and child on Aniwa. Let no evil befall them, or by this pledge I and my people will avenge it." This act of the old chief did much to insure the future safety of Paton and his family.

Aniwa is a small island, only nine miles long by three and one-half wide. There is a scarcity of rain, but the heavy dews and moist atmosphere keep the land covered with verdure. The natives were like those on Tanna, although they spoke a different language.

They were well received by the natives, who escorted them to their temporary abode, and watched them at their meals. The first duty was to build a house. An elevated site was purchased, where it was afterward learned all the bones and refuse of the Aniwan cannibal feast, for years, had been buried. The natives probably thought that, when they disturbed these, the missionary and his helpers would drop dead.

In building the house, an incident occurred which afterward proved of great benefit to Paton. One day, having need of some nails and tools, he picked up a chip and wrote a few words on it. Handing it to an old chief, he told him to take it to Mrs. Paton. When the chief saw her look at the chip and then get the things needed, he was filled with amazement. From that time on he took great interest in the work of the mission, and when the Bible was being translated into the Aniwa language he rendered invaluable aid.

Another chief, with his two sons, visited the mission-house and was much interested; but when they were returning home, one of his sons became very ill. Of course he thought the missionary was to blame, and threatened to kill the latter; but when, by the use of proper medicine, Paton brought the boy back to health again, the chief went to the opposite extreme, and was ever afterward a most devoted helper.

The first convert on Aniwa was the chief Mamokei. He often came to drink tea with the missionary family, and afterward brought with him chief Naswai and his wife; and all three were soon converted. Mamokei brought his little daughter to be educated in the mission. Many orphan children were also put under their care, and often these little children warned them of plots against their lives.

In the early part of the work on Aniwa, an incident happened which was amusing as well as romantic. A young Aniwan was in love with a young widow, living in an island village. Unfortunately, there were thirty other young men who also were suitors; and as the one who married her would probably be killed by the others, none dared to venture. After consulting with Paton, the young man went to her village at night and stole away with her. The others were furious, but were pacified by Paton, who made them believe she was not worth troubling themselves over. After three weeks had passed, the young man came out of hiding, and asked permission to bring her to the mission-house, which was granted. The next day she appeared in time for services. As the distinguishing feature of a Christian on Aniwa is that he wears more clothing than the heathen native, and as this young lady wished to show very plainly in what direction her sympathies extended, she appeared on the scene clad in a variety and abundance of clothing which it would be hard to equal. It was mostly European, at least. Over her native grass skirt she wore a man's drab-colored great-coat, sweeping over her heels. Over this was a vest, and on her head was a pair of trousers, one leg trailing over each shoulder. On one shoulder, also, was a red shirt, on the other a striped one; and, last of all, a red shirt was twisted around her head as a turban.

Many stories might be told illustrating the results of the early efforts of the missionary, but we pass on to that of the sinking of the well. As has already been said, there is little rain on Aniwa. The juice of the cocoanut is largely used by the natives in place of drinking-water. Paton resolved to sink a well, much to the astonishment of the natives, who, when he explained his plan to them, thought him crazy. He began to dig; and the friendly old chief kept men near him all the time, for fear he would take his own life, for they thought surely he must have gone mad. He managed to get some of the natives to help him, paying them in fish-hooks; but when the depth of twelve feet was reached the sides of the excavation caved in, and after that no native would enter it. Paton then constructed a derrick; and they finally consented to help pull up the loaded pails, while he dug. Day after day he toiled, till the hole was thirty feet deep. Still no water was found. That day he said to the old chief, "I think Jehovah God will give us water to-morrow from that hole." But the chief said they expected to see him fall through into the sea. Next morning he sunk a small hole in the bottom of the well, and from this hole there spurted a stream of water. Filling the jug with the water, he passed it round to the natives, telling them to examine and taste it. They were so awe-stricken that not one dared look over the edge into the well. At last they formed a line, holding each other by the hand, and first one looked over, then the next, etc., till all had seen the water in the well. When they were told that they all could use the water from that well, the old chief exclaimed, "Missi, what can we do to help you now?" He directed them to bring coral rock to line the well with, which they did with a will.

That was the beginning of a new era on Aniwa. The following Sunday the chief preached a sermon on the well. In the days that followed multitudes of natives brought their idols to the mission, where they were destroyed. Henceforth Christianity gained a permanent foothold on the island.

In 1869 the first communion was held, twelve out of twenty applicants being admitted to the church. In speaking of his emotions during the first communion, Paton says, "I shall never taste a deeper bliss until I gaze on the glorified face of Jesus himself."

In 1884 he returned to Scotland, his main object being to secure £6,000 for a mission-ship. He addressed many assemblages of different kinds, and succeeded in getting not only the £6,000 required, but £3,000 beside. He returned to Aniwa in 1886, and continued his work.

Recently he again visited England, and also the United States. He is now back on Aniwa — Aniwa, no longer a savage island, but by the grace of God a Christian land. There he expects to remain till summoned to his reward before the heavenly throne.

In this sketch an attempt has been made to give only a brief account of the work of this great missionary. No adequate idea can be given of his untiring zeal, his forgetfulness of self, and his simple faith in God. It is probable that no one has ever visited America in the interest of foreign missions who has made so deep an impression of the triumphs of the gospel among vicious and degraded peoples as has the eminent missionary hero, John G. Paton.

From Great Missionaries of the Church by Charles Creegan and Josephine Goodnow. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, ©1895.

John Gibson Paton was born May 24, 1824, near Dumfries, in the south of Scotland. His father was a stocking-maker; and although his family was little blessed in this world's goods, it was devoutly religious. When young John had reached his fifth year, the family moved to a new home in the ancient village of Torthorwald.

Their new home was of the usual thatched cottage, plainly but substantially built. It was one-story, and was divided into three rooms. One end room served as the living-room of the family, the other as a shop, and the middle one was the family sanctuary. To the sanctuary the father retired after each meal to offer up prayer in behalf of his family. Paton himself says: "We occasionally heard the pathetic echoes of a trembling voice, pleading as if for life; and we learned to slip out and in past that door on tiptoe, not to disturb that holy colloquy." Is it strange that from this family there should come three ministers of the gospel?

In early boyhood John was sent to the parish school, presided over by a man named Smith, who, although of high scholarship, was often unreasonable when in a rage. At one time his temper got the best of him, and he unjustly punished Paton, who ran home. Returning at his mother's entreaty, he was again abused, and left the school never to return. He now began to learn his father's trade, making an effort at the same time to keep up his studies. The work was hard, and he toiled from six in the morning until ten at night. At this time he learned much in a mechanical line which was of use to him later in the missionary field. He saved enough money from his wages to enable him to attend Dumfries Academy for six weeks. As a result of his earnest endeavor to keep up his studies since leaving the parish school, he was able now as a young man to obtain a position as district visitor and tract distributor of the West Campbell Street Reformed Presbyterian Church in Glasgow, with the privilege of attending the Free Church Normal Seminary. There were two applicants for the position; and as the trustees could not decide between them, they offered to let them work together and divide the salary, which was £50 a year.

Paton's health failed him, and he returned home. After recovering fully he returned to Glasgow, where he had a hard struggle with poverty. At one time, having no money, he secured a place as teacher of the Mary Hill Free School. This school had a bad reputation, many teachers having been forced to leave it because of trouble with the scholars. Paton managed by force of kindness to make friends of all the pupils; and when he finally left, the school was in a more prosperous condition than it had ever been before.

After leaving the school, he took a position as a worker in the Glasgow city mission. In this work he was remarkably successful. For ten years he was engaged in these labors, keeping up the study of theology all the time. Then, hearing that a helper was wanted to join the Rev. John Inglis in the New Hebrides, he offered himself and was accepted. This step was distasteful to many, who insisted that there were heathen enough at home; but, as Paton says, those who spoke thus invariably neglected the home heathen themselves. On the 16th of April, 1858, Mr. and Mrs. Paton set sail from Scotland in the Clutha for New Hebrides.

They stopped a few days at Melbourne, and from there sailed for Aneityum, the most southern of the New Hebrides. In twelve days they arrived off Aneityum; but the captain, a profane and hard-hearted man, refused to land them, and the landing was made with great difficulty, with the help of Dr. Geddie, in mission boats. They decided to settle on the eastern shore of Tanna, a small island a few miles north of Aneityum, which was inhabited by ferocious savages. Mr. and Mrs. Mathieson, co-laborers with them, settled on the northwestern shore of the same island.

The natives on Tanna were sunk to the lowest depths of heathenism, going about with no covering save an apron and paint — having no ideas of right or wrong, worshipping and fearing numerous gods, living in a continual dread of evil spirits, constantly fighting among themselves, and always eating the bodies of the slain — such were the creatures whom Paton and his wife hoped to bring to a knowledge of the gospel.

They landed on Tanna the 5th of November, 1858. On the 15th of February, 1859, a child was born to them. Mrs. Paton's health from this time on was very feeble, and on March 3rd she died of a sudden attack of pneumonia. Unaided and alone, the bereaved husband buried his beloved wife. Over her body he placed a mound of stones, making it as attractive as he could, and then with a heavy heart turned to his work.

Soon after the child, a boy, followed the mother. These two sorrows came as a terrible blow to Paton, and for some time he was prostrated. He rallied, however; and began to work hard and steadily to enlighten those poor savages, who upon every occasion robbed and abused him.

Mr. Paton, writing of this period, says: "On beholding these natives in their paint and nakedness and misery, my heart was as full of horror as of pity. Had I given up my much-beloved work and my dear people in Glasgow, with so many delightful associates, to consecrate my life to these degraded creatures? Was it possible to teach them right and wrong, to Christianize or even to civilize them? But that was only a passing feeling. I soon got as deeply interested in them, and all that tended to advance them, and to lead them to the knowledge of Jesus, as ever I had been in my work in Glasgow."

The greatest opposition to his work was occasioned by the godless traders on the island, who caused more trouble than did the natives themselves. These traders did not relish the idea of the natives being taught the gospel, for they feared to lose their influence over them. They incited the different tribes to fight with each other, and then sold arms to the contestants. They stirred up bad feeling against the missionaries, and urged the natives to either kill or drive them away.

From the time he landed until he left Tanna, Paton was in continual danger of losing his life. Again and again armed bands came to his house at night to kill him. He himself said that he knew of fifty times when his life was in imminent danger, and his escape was due solely to the grace of God. Only once did he resort to force, or rather the appearance of force. A cannibal entered his house, and would have killed him, had he not raised an empty pistol, at sight of which the cowardly fellow fled.

The feeling toward him became so hostile that he was obliged at last to leave his house, and take refuge in the village of a friendly chief named Nowar. Here he prepared to leave that part of the island, and sail around to Mr. Mathieson's station. He secured a canoe, but when he went to launch it he found there were no paddles. After he had managed to get these, the chief Arkurat refused to let him go. Having prevailed upon the vacillating savage to consent, he finally sailed away with his three native helpers and a boy. The wind and waves, however, forced them to put back, and after five hours of hard rowing they returned to the spot they had left. The only way left now was to walk overland. He got a friendly native to show him the path, and after escaping death most miraculously on the way, arrived at Mr. Mathieson's. Here they were still persecuted. At one time the mission buildings were fired, but a tornado which suddenly came up extinguished the flames. On the day following, the ship which had been sent to rescue them arrived and they embarked. Thus Paton had to abandon his work on Tanna, after toiling there over three years.

For a time he sought needed rest and change in Australia, where he presented the cause of missions to the churches. On many occasions he came into contact with the aborigines of that continent, and on every occasion his love for missionary work was exhibited. At one time, when a crowd of savages crazed with rum were fighting among themselves, he went among them, and by his quiet and persistent coaxing, managed to get them all to lie down and sleep off the effects of the spirits.

From Australia, Paton went to Scotland. He traveled all over the country, speaking in behalf of the mission. While in Scotland he married Margaret Whitecross, a woman well fitted to be the wife and helper of such a man. Leaving Scotland in the latter part of 1864, they arrived in the New Hebrides in the early part of 1865.

In 1866 they settled on Aniwa, an island near Tanna. The old Tannese chief, Nowar, who had always been friendly to Paton, was very anxious to have him settle on Tanna. Seeing that this was impossible, Nowar took from his arm the white shells, insignia of chieftainship, and binding them to the arm of a visiting Aniwan chief, said: "By these you promise to protect my missionary and his wife and child on Aniwa. Let no evil befall them, or by this pledge I and my people will avenge it." This act of the old chief did much to insure the future safety of Paton and his family.

Aniwa is a small island, only nine miles long by three and one-half wide. There is a scarcity of rain, but the heavy dews and moist atmosphere keep the land covered with verdure. The natives were like those on Tanna, although they spoke a different language.

They were well received by the natives, who escorted them to their temporary abode, and watched them at their meals. The first duty was to build a house. An elevated site was purchased, where it was afterward learned all the bones and refuse of the Aniwan cannibal feast, for years, had been buried. The natives probably thought that, when they disturbed these, the missionary and his helpers would drop dead.

In building the house, an incident occurred which afterward proved of great benefit to Paton. One day, having need of some nails and tools, he picked up a chip and wrote a few words on it. Handing it to an old chief, he told him to take it to Mrs. Paton. When the chief saw her look at the chip and then get the things needed, he was filled with amazement. From that time on he took great interest in the work of the mission, and when the Bible was being translated into the Aniwa language he rendered invaluable aid.

Another chief, with his two sons, visited the mission-house and was much interested; but when they were returning home, one of his sons became very ill. Of course he thought the missionary was to blame, and threatened to kill the latter; but when, by the use of proper medicine, Paton brought the boy back to health again, the chief went to the opposite extreme, and was ever afterward a most devoted helper.

The first convert on Aniwa was the chief Mamokei. He often came to drink tea with the missionary family, and afterward brought with him chief Naswai and his wife; and all three were soon converted. Mamokei brought his little daughter to be educated in the mission. Many orphan children were also put under their care, and often these little children warned them of plots against their lives.

In the early part of the work on Aniwa, an incident happened which was amusing as well as romantic. A young Aniwan was in love with a young widow, living in an island village. Unfortunately, there were thirty other young men who also were suitors; and as the one who married her would probably be killed by the others, none dared to venture. After consulting with Paton, the young man went to her village at night and stole away with her. The others were furious, but were pacified by Paton, who made them believe she was not worth troubling themselves over. After three weeks had passed, the young man came out of hiding, and asked permission to bring her to the mission-house, which was granted. The next day she appeared in time for services. As the distinguishing feature of a Christian on Aniwa is that he wears more clothing than the heathen native, and as this young lady wished to show very plainly in what direction her sympathies extended, she appeared on the scene clad in a variety and abundance of clothing which it would be hard to equal. It was mostly European, at least. Over her native grass skirt she wore a man's drab-colored great-coat, sweeping over her heels. Over this was a vest, and on her head was a pair of trousers, one leg trailing over each shoulder. On one shoulder, also, was a red shirt, on the other a striped one; and, last of all, a red shirt was twisted around her head as a turban.

Many stories might be told illustrating the results of the early efforts of the missionary, but we pass on to that of the sinking of the well. As has already been said, there is little rain on Aniwa. The juice of the cocoanut is largely used by the natives in place of drinking-water. Paton resolved to sink a well, much to the astonishment of the natives, who, when he explained his plan to them, thought him crazy. He began to dig; and the friendly old chief kept men near him all the time, for fear he would take his own life, for they thought surely he must have gone mad. He managed to get some of the natives to help him, paying them in fish-hooks; but when the depth of twelve feet was reached the sides of the excavation caved in, and after that no native would enter it. Paton then constructed a derrick; and they finally consented to help pull up the loaded pails, while he dug. Day after day he toiled, till the hole was thirty feet deep. Still no water was found. That day he said to the old chief, "I think Jehovah God will give us water to-morrow from that hole." But the chief said they expected to see him fall through into the sea. Next morning he sunk a small hole in the bottom of the well, and from this hole there spurted a stream of water. Filling the jug with the water, he passed it round to the natives, telling them to examine and taste it. They were so awe-stricken that not one dared look over the edge into the well. At last they formed a line, holding each other by the hand, and first one looked over, then the next, etc., till all had seen the water in the well. When they were told that they all could use the water from that well, the old chief exclaimed, "Missi, what can we do to help you now?" He directed them to bring coral rock to line the well with, which they did with a will.

That was the beginning of a new era on Aniwa. The following Sunday the chief preached a sermon on the well. In the days that followed multitudes of natives brought their idols to the mission, where they were destroyed. Henceforth Christianity gained a permanent foothold on the island.

In 1869 the first communion was held, twelve out of twenty applicants being admitted to the church. In speaking of his emotions during the first communion, Paton says, "I shall never taste a deeper bliss until I gaze on the glorified face of Jesus himself."

In 1884 he returned to Scotland, his main object being to secure £6,000 for a mission-ship. He addressed many assemblages of different kinds, and succeeded in getting not only the £6,000 required, but £3,000 beside. He returned to Aniwa in 1886, and continued his work.

Recently he again visited England, and also the United States. He is now back on Aniwa — Aniwa, no longer a savage island, but by the grace of God a Christian land. There he expects to remain till summoned to his reward before the heavenly throne.

In this sketch an attempt has been made to give only a brief account of the work of this great missionary. No adequate idea can be given of his untiring zeal, his forgetfulness of self, and his simple faith in God. It is probable that no one has ever visited America in the interest of foreign missions who has made so deep an impression of the triumphs of the gospel among vicious and degraded peoples as has the eminent missionary hero, John G. Paton.

From Great Missionaries of the Church by Charles Creegan and Josephine Goodnow. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, ©1895.

_by__A.B.%20Bruce_-160.webp)