Others like this day we fight! Features >>

About the Book

"This Day We Fight!" by Francis Frangipane emphasizes the importance of engaging in spiritual warfare and standing firm in faith against the enemy's attacks. The book offers practical insights and strategies for overcoming spiritual battles and empowering believers to live victoriously in Christ.

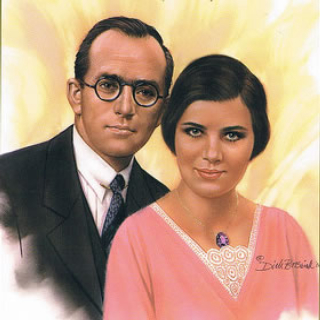

John and Betty Stam

The year 1934. Americans John and Betty Stam were serving as missionaries in China. One morning Betty was bathing her three-month-old daughter Helen Priscilla Stam when Tsingteh's city magistrate appeared. Communist forces were near, he warned, and urged the Stams to flee.

So John Stam went out to investigate the situation for himself. He received conflicting reports. Taking no chances, he arranged for Betty and the baby to be escorted away to safety if need be. But before the Stams could make their break, the Communists were inside the city. By little-known paths, they had streamed over the mountains behind government troops. Now gun shots sounded in the streets as looting began. The enemy beat on the Stams' own gate.

A faithful cook and maid at the mission station had stayed behind. The Stams knelt with them in prayer. But the invaders were pounding at the door. John opened it and spoke courteously to the four leaders who entered, asking them if they were hungry. Betty brought them tea and cakes. The courtesy meant nothing. They demanded all the money the Stams had, and John handed it over. As the men bound him, he pleaded for the safety of his wife and child. The Communists left Betty and Helen behind as they led John off to their headquarters.

Before long, they reappeared, demanding mother and child. The maid and cook pleaded to be allowed to accompany Betty.

"No," barked the captors, and threatened to shoot.

"It is better for you to stay here," Betty whispered. "If anything happens to us, look after the baby."

[When we consecrate ourselves to God, we think we are making a great sacrifice, and doing lots for Him, when really we are only letting go some little, bitsie trinkets we have been grabbing, and when our hands are empty, He fills them full of His treasures. --Betty Stam]

Betty was led to her husband's side. Little Helen needed some things and John was allowed to return home under guard to fetch them. But everything had been stolen. That night John was allowed to write a letter to mission authorities. "My wife, baby and myself are today in the hands of the Communists in the city of Tsingteh. Their demand is twenty thousand dollars for our release. . . . We were too late. The Lord bless and guide you. As for us, may God be glorified, whether by life or by death."

Prisoners in the local jail were released to make room for the Stams. Frightened by rifle fire, the baby cried out. One of the Reds said, "Let's kill the baby. It is in our way." A bystander asked, "Why kill her? What harm has she done?"

"Are you a Christian?" shouted one of the guards.

The man said he was not; he was one of the prisoners just released.

"Will you die for this foreign baby?" they asked. As Betty hugged Helen to her chest, the man was hacked to pieces before her eyes.

Terror in the Streets

The next morning their captors led the Stams toward Miaosheo, twelve miles distant. John carried little Helen, but Betty, who was not physically strong, owing to a youthful bout with inflammatory rheumatitis was allowed to ride a horse part of the way. Terror reigned in the streets of Miaosheo. Under guard, the foreign family was hustled into the postmaster's shop.

"Where are you going?" asked the postmaster, who recognized them from their previous visits to his town. "We do not know where they are going, but we are going to heaven," answered John. He left a letter with the postmaster. "I tried to persuade them to let my wife and baby go back from Tsingteh with a letter to you, but they would not let her. . . ."

That night the three were held in the house of a wealthy man who had fled. They were guarded by soldiers. John was tied to a post all that cold night, but Betty was allowed enough freedom to tend the baby. As it turned out, she did more than that.

Execution

The next morning the young couple were led through town without the baby. Their hands were tightly bound, and they were stripped of their outer garments as if they were common criminals. John walked barefoot. He had given his socks to Betty. The soldiers jeered and called the town’s folk to come see the execution. The terrified people obeyed.

On the way to the execution, a medicine-seller, considered a lukewarm Christian at best, stepped from the crowd and pleaded for the lives of the two foreigners. The Reds angrily ordered him back. The man would not be stilled. His house was searched, a Bible and hymnbook found, and he, too was dragged away to die as a hated Christian.

John pleaded for the man’s life. The Red leader sharply ordered him to kneel. As John was speaking softly, the Red leader swung his sword through the missionary’s throat so that his head was severed from his body. Betty did not scream. She quivered and fell bound beside her husband’s body. As she knelt there, the same sword ended her life with a single blow.

Betty

Betty Scott was born in the United States but reared in China as the daughter of missionaries. She came to the United States and attended Wilson College in Pennsylvania. Betty prepared to follow in her parents’ footsteps and work in China or wherever else the Lord directed her.

But China it proved to be. At a prayer meeting for China, she met John Stam and a friendship developed that ripened into love. Painfully they recognized that marriage was not yet possible. “The China Inland Mission has appealed for men, single men, to work in sections where it would be impossible to take a woman until more settled work has commenced,” wrote John. He committed the matter to the Lord, whose work, he felt, must come before any human affection. At any rate, Betty would be leaving for China before him, to work in an entirely different region, and so they must be separated anyhow. As a matter of fact, John had not yet even been accepted by the China Inland Mission whereas Betty had. They parted after a long tender day, sharing their faith, picnicking, talking, and praying.

Betty sailed while John continued his studies. On July 1, 1932, John, too, was accepted for service in China. Now at least he could head toward the same continent as Betty. He sailed for Shanghai.

Meanwhile, Betty found her plans thwarted. A senior missionary had been captured by the Communists in the region where she was to have worked. The mission directors decided to keep her in a temporary station, and later ill-health brought her to Shanghai. Thus without any choice on her part, she was in Shanghai when John landed in China. Immediately they became engaged and a year later were married, long before they expected it. In October, 1934 Helen Priscilla was born to them. What would become of her now that her parents John and Betty were dead?

In the Hills

For two days, local Christians huddled in hiding in the hills around Miaosheo. Among them was a Chinese evangelist named Mr. Lo. Through informants, he learned that the Communists had captured two foreigners. At first he did not realize that these were John and Betty Stam, with whom he had worked, but as he received more details, he put two and two together. As soon as government troops entered the valley and it was safe to venture forth, Mr. Lo hurried to town. His questions met with silence. Everyone was fearful that spies might report anyone who said too much.

An old woman whispered to Pastor Lo that there was a baby left behind. She nodded in the direction of the house where John and Betty had been chained their last night on earth. Pastor Lo hurried to the site and found room after room trashed by the bandits. Then he heard a muffled cry. Tucked by her mother in a little sleeping bag, Helen was warm and alive, although hungry after her two day fast.

The kindly pastor took the child in his arms and carried her to his wife. With the help of a local Christian family, he wrapped the bodies that still lay upon the hillside and placed them into coffins. To the crowd that gathered he explained that the missionaries had only come to tell them how they might find forgiveness of sin in Christ. Leaving others to bury the dead, he hurried home. Somehow Helen had to be gotten to safety.

Pastor Lo's own son, a boy of four, was desperately ill -- semi-conscious after days of exposure. Pastor Lo had to find a way to carry the children a hundred miles through mountains infested by bandits and Communists. Brave men were found willing to help bear the children to safety, but there was no money to pay them for their efforts. Lo had been robbed of everything he had.

From Beyond the Grave

But from beyond the grave, Betty provided. Tucked in Helen's sleeping bag were a change of clothes and some diapers. Pinned between these articles of clothing were two five dollar bills. It made the difference.

Placing the children in rice baskets slung from the two ends of a bamboo pole, the group departed quietly, taking turns carrying the precious cargo over their shoulders. Mrs. Lo was able to find Chinese mothers along the way to nurse Helen. On foot, they came safely through their perils. Lo's own boy recovered consciousness suddenly and sat up, singing a hymn.

Eight days after the Stams fell into Communist hands, another missionary in a nearby city heard a rap at his door. He opened it and a Chinese woman, stained with travel, entered the house, bearing a bundle in her arms. "This is all we have left," she said brokenly.

The missionary took the bundle and turned back the blanket to uncover the sleeping face of Helen Priscilla Stam. Many kind hands had labored to preserve the infant girl, but none kinder than Betty who had spared no effort for her baby even as she herself faced degradation and death.

Kathleen White has written an excellent and very readable biography John and Betty Stam, available from Bethany House Publishers (1988). She reports that Betty's alma mater, Wilson College in Pennsylvania, took over baby Helen's support and covered the costs of her college education. She added: "Helen is living in this country (USA) with her husband and family but does not wish her identity and whereabouts to be made known."

Resources:

Huizenga, Lee S. John and Betty Stam; Martyrs. Zondervan, 1935.

Pollock, John. Victims of the Long March and Other Stories. Waco, Texas.: Word Publishing, 1970.

Taylor, Mrs. Howard. The Triumph of John and Betty Stam. China Inland Mission, 1935.

The year 1934. Americans John and Betty Stam were serving as missionaries in China. One morning Betty was bathing her three-month-old daughter Helen Priscilla Stam when Tsingteh's city magistrate appeared. Communist forces were near, he warned, and urged the Stams to flee.

So John Stam went out to investigate the situation for himself. He received conflicting reports. Taking no chances, he arranged for Betty and the baby to be escorted away to safety if need be. But before the Stams could make their break, the Communists were inside the city. By little-known paths, they had streamed over the mountains behind government troops. Now gun shots sounded in the streets as looting began. The enemy beat on the Stams' own gate.

A faithful cook and maid at the mission station had stayed behind. The Stams knelt with them in prayer. But the invaders were pounding at the door. John opened it and spoke courteously to the four leaders who entered, asking them if they were hungry. Betty brought them tea and cakes. The courtesy meant nothing. They demanded all the money the Stams had, and John handed it over. As the men bound him, he pleaded for the safety of his wife and child. The Communists left Betty and Helen behind as they led John off to their headquarters.

Before long, they reappeared, demanding mother and child. The maid and cook pleaded to be allowed to accompany Betty.

"No," barked the captors, and threatened to shoot.

"It is better for you to stay here," Betty whispered. "If anything happens to us, look after the baby."

[When we consecrate ourselves to God, we think we are making a great sacrifice, and doing lots for Him, when really we are only letting go some little, bitsie trinkets we have been grabbing, and when our hands are empty, He fills them full of His treasures. --Betty Stam]

Betty was led to her husband's side. Little Helen needed some things and John was allowed to return home under guard to fetch them. But everything had been stolen. That night John was allowed to write a letter to mission authorities. "My wife, baby and myself are today in the hands of the Communists in the city of Tsingteh. Their demand is twenty thousand dollars for our release. . . . We were too late. The Lord bless and guide you. As for us, may God be glorified, whether by life or by death."

Prisoners in the local jail were released to make room for the Stams. Frightened by rifle fire, the baby cried out. One of the Reds said, "Let's kill the baby. It is in our way." A bystander asked, "Why kill her? What harm has she done?"

"Are you a Christian?" shouted one of the guards.

The man said he was not; he was one of the prisoners just released.

"Will you die for this foreign baby?" they asked. As Betty hugged Helen to her chest, the man was hacked to pieces before her eyes.

Terror in the Streets

The next morning their captors led the Stams toward Miaosheo, twelve miles distant. John carried little Helen, but Betty, who was not physically strong, owing to a youthful bout with inflammatory rheumatitis was allowed to ride a horse part of the way. Terror reigned in the streets of Miaosheo. Under guard, the foreign family was hustled into the postmaster's shop.

"Where are you going?" asked the postmaster, who recognized them from their previous visits to his town. "We do not know where they are going, but we are going to heaven," answered John. He left a letter with the postmaster. "I tried to persuade them to let my wife and baby go back from Tsingteh with a letter to you, but they would not let her. . . ."

That night the three were held in the house of a wealthy man who had fled. They were guarded by soldiers. John was tied to a post all that cold night, but Betty was allowed enough freedom to tend the baby. As it turned out, she did more than that.

Execution

The next morning the young couple were led through town without the baby. Their hands were tightly bound, and they were stripped of their outer garments as if they were common criminals. John walked barefoot. He had given his socks to Betty. The soldiers jeered and called the town’s folk to come see the execution. The terrified people obeyed.

On the way to the execution, a medicine-seller, considered a lukewarm Christian at best, stepped from the crowd and pleaded for the lives of the two foreigners. The Reds angrily ordered him back. The man would not be stilled. His house was searched, a Bible and hymnbook found, and he, too was dragged away to die as a hated Christian.

John pleaded for the man’s life. The Red leader sharply ordered him to kneel. As John was speaking softly, the Red leader swung his sword through the missionary’s throat so that his head was severed from his body. Betty did not scream. She quivered and fell bound beside her husband’s body. As she knelt there, the same sword ended her life with a single blow.

Betty

Betty Scott was born in the United States but reared in China as the daughter of missionaries. She came to the United States and attended Wilson College in Pennsylvania. Betty prepared to follow in her parents’ footsteps and work in China or wherever else the Lord directed her.

But China it proved to be. At a prayer meeting for China, she met John Stam and a friendship developed that ripened into love. Painfully they recognized that marriage was not yet possible. “The China Inland Mission has appealed for men, single men, to work in sections where it would be impossible to take a woman until more settled work has commenced,” wrote John. He committed the matter to the Lord, whose work, he felt, must come before any human affection. At any rate, Betty would be leaving for China before him, to work in an entirely different region, and so they must be separated anyhow. As a matter of fact, John had not yet even been accepted by the China Inland Mission whereas Betty had. They parted after a long tender day, sharing their faith, picnicking, talking, and praying.

Betty sailed while John continued his studies. On July 1, 1932, John, too, was accepted for service in China. Now at least he could head toward the same continent as Betty. He sailed for Shanghai.

Meanwhile, Betty found her plans thwarted. A senior missionary had been captured by the Communists in the region where she was to have worked. The mission directors decided to keep her in a temporary station, and later ill-health brought her to Shanghai. Thus without any choice on her part, she was in Shanghai when John landed in China. Immediately they became engaged and a year later were married, long before they expected it. In October, 1934 Helen Priscilla was born to them. What would become of her now that her parents John and Betty were dead?

In the Hills

For two days, local Christians huddled in hiding in the hills around Miaosheo. Among them was a Chinese evangelist named Mr. Lo. Through informants, he learned that the Communists had captured two foreigners. At first he did not realize that these were John and Betty Stam, with whom he had worked, but as he received more details, he put two and two together. As soon as government troops entered the valley and it was safe to venture forth, Mr. Lo hurried to town. His questions met with silence. Everyone was fearful that spies might report anyone who said too much.

An old woman whispered to Pastor Lo that there was a baby left behind. She nodded in the direction of the house where John and Betty had been chained their last night on earth. Pastor Lo hurried to the site and found room after room trashed by the bandits. Then he heard a muffled cry. Tucked by her mother in a little sleeping bag, Helen was warm and alive, although hungry after her two day fast.

The kindly pastor took the child in his arms and carried her to his wife. With the help of a local Christian family, he wrapped the bodies that still lay upon the hillside and placed them into coffins. To the crowd that gathered he explained that the missionaries had only come to tell them how they might find forgiveness of sin in Christ. Leaving others to bury the dead, he hurried home. Somehow Helen had to be gotten to safety.

Pastor Lo's own son, a boy of four, was desperately ill -- semi-conscious after days of exposure. Pastor Lo had to find a way to carry the children a hundred miles through mountains infested by bandits and Communists. Brave men were found willing to help bear the children to safety, but there was no money to pay them for their efforts. Lo had been robbed of everything he had.

From Beyond the Grave

But from beyond the grave, Betty provided. Tucked in Helen's sleeping bag were a change of clothes and some diapers. Pinned between these articles of clothing were two five dollar bills. It made the difference.

Placing the children in rice baskets slung from the two ends of a bamboo pole, the group departed quietly, taking turns carrying the precious cargo over their shoulders. Mrs. Lo was able to find Chinese mothers along the way to nurse Helen. On foot, they came safely through their perils. Lo's own boy recovered consciousness suddenly and sat up, singing a hymn.

Eight days after the Stams fell into Communist hands, another missionary in a nearby city heard a rap at his door. He opened it and a Chinese woman, stained with travel, entered the house, bearing a bundle in her arms. "This is all we have left," she said brokenly.

The missionary took the bundle and turned back the blanket to uncover the sleeping face of Helen Priscilla Stam. Many kind hands had labored to preserve the infant girl, but none kinder than Betty who had spared no effort for her baby even as she herself faced degradation and death.

Kathleen White has written an excellent and very readable biography John and Betty Stam, available from Bethany House Publishers (1988). She reports that Betty's alma mater, Wilson College in Pennsylvania, took over baby Helen's support and covered the costs of her college education. She added: "Helen is living in this country (USA) with her husband and family but does not wish her identity and whereabouts to be made known."

Resources:

Huizenga, Lee S. John and Betty Stam; Martyrs. Zondervan, 1935.

Pollock, John. Victims of the Long March and Other Stories. Waco, Texas.: Word Publishing, 1970.

Taylor, Mrs. Howard. The Triumph of John and Betty Stam. China Inland Mission, 1935.

Our Lives in His

Does our right standing before God depend on our becoming more like Jesus, or does our becoming more like Jesus flow from our right standing before God? I first began wrestling with that question twenty years ago as a college student. The Bible uses a variety of terms for what God has done for us in Christ — salvation, regeneration, justification, sanctification, adoption, election, redemption, glorification. The question I struggled to answer was, How do all of these terms relate to one another? More specifically and personally, when and how and in what sequence will they happen for me? Historically, my question was about the relationship between justification (being declared righteous before God) and sanctification (the ongoing progressive work by which we are conformed to the image of Jesus). Did justification precede and give rise to sanctification? Or was justification in some way based upon my sanctification? Resurrection and Redemption Romans 8:29–30 often sets the tone for the debate: For those whom [God] foreknew he also predestined to be conformed to the image of his Son, in order that he might be the firstborn among many brothers. And those whom he predestined he also called, and those whom he called he also justified, and those whom he justified he also glorified. Here we have a basic order: foreknown, predestined, called, justified, glorified. The question was how the rest of the saving realities — saved, redeemed, adopted, and sanctified — fit into the picture. As I wrestled, I came across a book that proved to be a watershed for me: Resurrection and Redemption by Richard Gaffin, a longtime professor at Westminster Theological Seminary. The book is small — around 150 pages — but packs a theological punch. The basic thesis of the book has been profoundly helpful to me in thinking through how to bring the various biblical threads together on all that God has done for us in Christ. We Will Be Raised The book begins with the claim that the unity of the resurrection of Christ and the resurrection of believers runs through the New Testament, citing texts like these: 1 Corinthians 15:20: “Christ has been raised from the dead, the firstfruits of those who have fallen asleep.” Colossians 1:18: “[Christ] is the head of the body, the church. He is the beginning, the firstborn from the dead, that in everything he might be preeminent.” 1 Corinthians 15:16–18: “If the dead are not raised, not even Christ has been raised. And if Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile and you are still in your sins. Then those also who have fallen asleep in Christ have perished.” 2 Corinthians 4:14: “[We know] that he who raised the Lord Jesus will raise us also with Jesus.” Each of these passages expresses the reality that the resurrection of Christ is both unique and necessarily connected to our future resurrection. He is the firstfruits, the firstborn from the dead. He is the pioneer, the inaugurator, the forerunner who leads the way. We Have Been Raised This unity, however, is not merely a connection between Christ’s past resurrection and our future resurrection. The New Testament also stresses that we have already been, in some sense, raised with Christ. Ephesians 2:5–6: “Even when we were dead in our trespasses, [God] made us alive together with Christ — by grace you have been saved — and raised us up with him and seated us with him in the heavenly places in Christ Jesus.” Colossians 2:12–13: “. . . having been buried with him in baptism, in which you were also raised with him through faith in the powerful working of God, who raised him from the dead. And you, who were dead in your trespasses and the uncircumcision of your flesh, God made alive together with him, having forgiven us all our trespasses.” Romans 6:3–4: “Do you not know that all of us who have been baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death? We were buried therefore with him by baptism into death, in order that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might walk in newness of life.” These passages teach that we are united to Christ not only in his resurrection, but in the whole of his life and death as well. We have died with Christ. We have been crucified with Christ. We have been raised with Christ. We have been seated with Christ. From passages like these, Gaffin draws the conclusion that this existential union with Christ is the most basic element of Paul’s teaching on salvation. Inner Man and Outer Man The personal and existential union between us and Christ is intertwined with being chosen in Christ before the foundation of the world as well as being in some sense “in Christ” when he was crucified, buried, and raised in the first century. In other words, while we can distinguish between redemption planned (in eternity past), redemption accomplished (in history two thousand years ago), and redemption applied (in our own individual lives), we can never separate them, since all of them take place “in Christ.” Gaffin draws attention to the already-not-yet dimension of redemption applied. In particular, the resurrection of Jesus has been refracted in the experience of the believer. We have already been raised with Christ (Ephesians 2:5), but we have not yet been raised with Christ (1 Corinthians 15:12–20). Gaffin uses Paul’s distinction between the inner man and the outer man to make this point. We have been raised in the inner man, while we await the resurrection of the outer man — that is, the resurrection of the body at Christ’s second coming. Paul makes this point explicitly in 2 Corinthians 4:16: “Though our outer self is wasting away, our inner self is being renewed day by day.” What then does this have to do with the order of salvation and the various terms used to describe what God has done for us in Christ? Let me attempt to express the lessons in my own words. Five Glimpses of One Reality When God saves us, the fundamental thing he does is unite us to Christ by faith. “When God saves us, the fundamental thing he does is unite us to Christ by faith.” Union with the crucified and risen Lord Jesus is what salvation fundamentally is. But in order to help us understand the wonder and glory of our union with Christ, God gives us multiple word pictures or metaphors to reveal the significance of what Christ has done for us. Each of these word pictures or images enables us to comprehend the incomprehensible fact of our union with the Lord Jesus. We can unpack union with Christ in terms of a law court, in which words like guilt and condemnation, righteousness and justification figure prominently. We can unpack union with Christ using imagery from the temple, in which holiness and impurity, sanctification and cleansing are used. We can unpack union with Christ using familial imagery, with the language of new birth and adoption taking center stage. We can unpack union with Christ using the image of slavery and redemption, with mentions of bondage and captivity, of purchasing and freedom. We can unpack union with Christ with the language of salvation and deliverance, of danger and rescue by a Savior. Rather than trying to put the different terms into the exact sequence, we can instead see them as multiple ways that God has chosen to reveal the greatness and glory of what he has done for us. Five Already-Not-Yet Pictures More than that, because of the already-not-yet dimension of our salvation, we can see that each of these word pictures contains three distinct phases: a definitive positional phase, an ongoing progressive phase, and a climactic final phase. If we run through the images again, we might say the following: In terms of the law court, we are guilty and stand condemned, but Christ lives, dies, and is raised on our behalf, and therefore God declares us righteous in him. This is definitive and has to do with a new position and legal status based on the finished work of Christ. As a result, we leave the courtroom and seek to live upright and godly lives, walking in righteousness before God, as we wait for the day when we are publicly vindicated as his people when he bodily raises us from the dead. In terms of the temple, God is holy and therefore cleanses the impure and sets apart the common for holy use. There is a decisive cleansing and sanctifying work when we trust in Christ (positional), and then the rest of our lives is an attempt to live holy lives, increasingly and progressively set apart from sin and evil, while we await our full and final cleansing in the new heavens and new earth. In terms of the family, God decisively causes us to be born again, and then we seek to walk faithfully as his children. Or alternatively, he adopts us into his family (that’s conversion), and we now walk as obedient sons, as we wait for the final declaration of our sonship and conformity to the image of his Son when we are glorified. In terms of slavery and redemption, we were enslaved to sin and death, and God decisively liberates us when he unites us to his Son. From then on, we seek to increasingly and progressively live as free men, since it is for freedom that Christ has set us free, as we wait for the redemption of our bodies on the last day. In terms of danger and rescue, God delivers us from the penalty of sin (death), and then throughout our lives increasingly rescues us from the power of sin, all in anticipation of the day when we’ll be completely delivered from the presence of sin in his eternal kingdom. For Me and Conforming Me Resurrection and Redemption proved to be a watershed for me because the book resolved the tension over whether my right standing with God (justification) depended on my increasing conformity to Jesus (progressive sanctification). “Justification is by faith alone, because faith unites me to Christ, who is my righteousness.” Gaffin assured me, with Scripture, that my position before God — whether we’re talking about the courtroom, the temple, or the family — was decisively and definitively settled, simply by trusting in Jesus. Justification is by faith alone, because faith unites me to Christ, who is my righteousness. The righteousness beneath my justification is not something worked in me by God, but something accomplished for me — outside of me — by Christ. Union with him — his life, death, and resurrection — puts me right with God, so that God is completely for me. Then, flowing from this new standing and position before God, God begins to progressively and increasingly conform me to the image of Jesus. The work is often slow, frequently painful. Sin remains, even if the wages of sin no longer hang over me. But my pursuit of holiness and obedience to God is rooted in the finished work of Jesus, both in history and in my life, and I hope for the coming day when God raises me from the dead and publicly displays what he has done for me and in me. Article by Joe Rigney

.epub-160.webp)