Others like the prayer warrior's way Features >>

Prayer Warrior

The Prayer Of Jabez

The Power Of A Praying Woman

The Power Of A Praying Life

The Power Of A Praying Nation

The Power Of Praise And Worship

Prayer For Patient Waiting - II Thessalonians 3:5

Prayer Altars - A Strategy That Is Changing Nations

Operating In The Courts Of Heaven

How To Pray With Passion And Power

About the Book

"The Prayer Warrior's Way" by Cindy Trimm is a guide to developing a powerful and effective prayer life. Trimm provides practical strategies and insights for engaging in spiritual warfare, interceding for others, and deepening your relationship with God through prayer. She emphasizes the importance of aligning your prayers with God's will and standing firm in faith. Through engaging stories and practical advice, Trimm shows readers how to become strong and effective prayer warriors in their own lives.

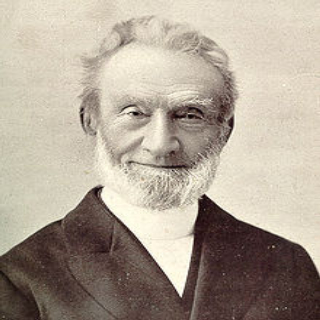

George Müller

Among the greatest monuments of what can be accomplished through simple faith in God are the great orphanages covering thirteen acres of ground on Ashley Downs, Bristol, England. When God put it into the heart of George Muller to build these orphanages, he had only two shillings (50 cents) in his pocket. Without making his wants known to any man, but to God alone, over a million, four hundred thousand pounds ($7,000,000) were sent to him for the building and maintaining of these orphan homes. When the writer first visited them, near the time of Mr. Muller's death, there were five immense buildings of solid granite, capable of accommodating two thousand orphans. In all the years since the first orphans arrived the Lord had sent food in due time, so that they had never missed a meal for want of food.

Although George Muller became famous as one of the greatest men of prayer known to history, he was not always a saint. He wandered very deep into sin before he was brought to Christ. He was born in the kingdom of Prussia, in 1805. His father was a revenue collector for the government, and was a worldly-minded man. He supplied George and his brother with plenty of money when they were boys, and they spent it very foolishly. George deceived his father about how much money he spent, and also as to how he spent it. He also stole the government money during his father's absence.

At ten years of age, George was sent to the cathedral classical school at Halberstadt. His father wanted to make a Lutheran clergyman of him, not that he might serve God, but that he might have an easy and comfortable living from the State Church. "My time," says he. "was now spent in studying, reading novels, and indulging, though so young, in sinful practices. Thus it continued until I was fourteen years old, when my mother was suddenly removed. The night she was dying, I, not knowing of her illness, was playing cards until two in the morning, and on the next day, being the Lord's day, I went with some of my companions in sin to a tavern, and then, being filled with strong beer, we went about the streets half intoxicated."

"I grew worse and worse," says he. "Three or four days before I was confirmed (and thus admitted to partake of the Lord's supper), I was guilty of gross immorality; and the very day before my confirmation, when I was in the vestry with the clergyman to confess my sins (according to the usual practice), after a formal manner, I defrauded him; for I handed over to him only a twelfth part of the fee which my father had given me for him."

A few solemn thoughts and desires to lead a better life came to him, but he continued to plunge deeper and deeper into sin. Lying, stealing, gambling, novel-reading, licentiousness, extravagance, and almost every form of sin was indulged in by him. No one would have imagined that the sinful youth would ever become eminent for his faith in God and for his power in prayer. He robbed his father of certain rents which his father had entrusted him to collect, falsifying the accounts of what he had received and pocketing the balance. His money was spent on sinful pleasures, and once he was reduced to such poverty that, in order to satisfy his hunger, he stole a piece of coarse bread, the allowance of a soldier who was quartered in the house where he was. In 1821 he set off on an excursion to Magdeburg, where he spent six days in "much sin." He then went to Brunswick, and put up at an expensive hotel until his money was exhausted. He then put up at a fine hotel in a neighboring village, intending to defraud the hotel-keeper. But his best clothes were taken in lieu of what he owed. He then walked six miles to another inn, where he was arrested for trying to defraud the landlord. He was imprisoned for this crime when sixteen years of age.

After his imprisonment young Muller returned to his home and received a severe thrashing from his angry father. He remained as sinful in heart as ever, but in order to regain his father's confidence he began to lead a very exemplary life outwardly, until he had the confidence of all around him. His father decided to send him to the classical school at Halle, where the discipline was very strict, but George had no intention of going there. He went to Nordhausen instead, and by using many lies and entreaties persuaded his father to allow him to remain there for two years and six months, till Easter, 1825. Here he studied diligently, was held up as an example to the other students, and became proficient in Latin, French, History, and his own language (German). "But whilst I was outwardly gaining the esteem of my fellow-creatures," says he, "I did not care in the least about God, but lived secretly in much sin, in consequence of which I was taken ill, and for thirteen weeks confined to my room. All this time I had no real sorrow of heart, yet being under certain natural impressions of religion, I read through Klopstock's works, without weariness. I cared nothing about the Word of God."

"Now and then I felt I ought to become a different person," says he, "and I tried to amend my conduct, particularly when I went to the Lord's supper, as I used to do twice every year, with the other young men. The day previous to attending that ordinance I used to refrain from certain things, and on the day itself I was serious, and also swore once or twice to God with the emblem of the broken body in my mouth, to become better, thinking that for the oath's sake I should be induced to reform. But after one or two days were over, all was forgotten, and I was as bad as before."

He entered the University of Halle as a divinity student, with good testimonials. This qualified him to preach in the Lutheran state church. While at the university he spent all his money in profligate living. "When my money was spent," says he, "I pawned my watch and part of my linen and clothes, or borrowed in other ways. Yet in the midst of all this I had a desire to renounce this wretched life, for I had no enjoyment in it, and had sense enough left to see, that the end one day or other would be miserable; for I should never get a living. But I had no sorrow of heart on account of offending God."

At the University he formed the acquaintance of a miserable backslider, named Beta, who was trying by means of worldly pleasures to drown out his conviction of sin. They plunged into sin together, and in June, 1825, George was again taken sick. After his recovery they forged letters purporting to be from his parents. With these they obtained passports and set out to see Switzerland. Muller stole from the friends who accompanied him and the journey did not cost him so much as it did them. They returned home to finish up the vacation and then went back to the University, Muller having lied to his father about the trip to Switzerland.

At the University of Halle there were about nine hundred divinity students. All of these were allowed to preach, but Muller estimates that not nine of them feared the Lord. "One Saturday afternoon, about the middle of November, 1825," says he, "I had taken a walk with my friend Beta. On our return he said to me, that he was in the habit of going on Saturday evenings to the house of a Christian, where there was a meeting. On further inquiry he told me that they read the Bible, sang, prayed, and read a printed sermon. No sooner had I heard this, but it was to me as if I had found something after which I had been seeking all my life long. I immediately wished to go with my friend, who was not at once willing to take me; for knowing me as a merry young man, he thought I should not like this meeting. At last, however, he said he would call for me."

Describing the meeting, Muller said: "We went together in the evening. As I did not know the manners of the brethren, and the joy they have in seeing poor sinners, even in any measure caring about the things of God, I made an apology for coming. The kind answer of this dear brother I shall never forget. He said: 'Come as often as you please; house and heart are open to you."' After a hymn was sung they fell upon their knees, and a brother, named Kayser, who afterwards became a missionary to Africa, asked God's blessing on the meeting. "This kneeling down made a deep impression upon me," says Muller, "for I had never either seen any one on his knees, nor had I ever myself prayed on my knees. He then read a chapter and a printed sermon; for no regular meetings for expounding the Scriptures were allowed in Prussia, except an ordained clergyman was present. At the close we sang another hymn, and then the master of the house prayed." The meeting made a deep impression upon Muller. "I was happy," says he, "though if I had been asked why I was happy, I could not clearly have explained it."

"When we walked home, I said to Beta, all we have seen on our journey to Switzerland, and all our former pleasures, are as nothing in comparison with this evening. Whether I fell on my knees when I returned home I do not remember; but this I know, that I lay peaceful and happy in my bed. This shows that the Lord may begin his work in different ways. For I have not the least doubt that on that evening He began a work of grace in me, though I obtained joy without any deep sorrow of heart, and with scarcely any knowledge. But that evening was the turning point in my life. The next day, and Monday, and once or twice besides, I went again to the house of this brother, where I read the Scriptures with him and another brother; for it was too long for me to wait until Saturday came again."

"Now my life became very different, though not so, that my sins were all given up at once. My wicked companions were given up; the going to taverns was discontinued; the habitual practice of telling falsehoods was no longer indulged in, but still a few times more I spoke an untruth... I now no longer lived habitually in sin, though I was still often overcome and sometimes even by open sins, though far less frequently than before, and not without sorrow of heart. I read the Scriptures, prayed often, loved the brethren, went to church from right motives and stood on the side of Christ, though laughed at by my fellow students."

For a few weeks after his conversion Muller made rapid advancement in the Christian life, and he was greatly desirous of becoming a missionary. But he fell in love with a Roman Catholic girl, and for some time the Lord was well nigh forgotten. Then Muller saw a young missionary giving up all the luxuries of a beautiful home for Christ. This opened his eyes to his own selfishness and enabled him to give up the girl who had taken the place of Christ in his heart. "It was at this time," says he, "that I began to enjoy the peace of God, which passeth all understanding. In this my joy I wrote to my father and brother, entreating them to seek the Lord, and telling them how happy I was; thinking, that if the way to happiness were set before them, they would gladly embrace it. To my great surprise an angry answer was returned."

George could not enter any German missionary training institution without the consent of his father, and this he could not obtain. His father was deeply grieved that after educating him so that he could obtain a comfortable living as a clergyman he should turn missionary. George felt that he could no longer accept any money from him. The Lord graciously sent him means with which to complete his education. He taught German to some American college professors at the University, and they handsomely remunerated him for his services. He was now the means of winning a number of souls to Christ. He gave away thousands of religious tracts and papers, and spoke to many persons concerning the salvation of their souls.

Although, before his conversion, Muller had written to his father and told him about sermons he had preached, he never really preached a sermon until some time after his conversion. He thought to please his father by making him believe that he was preaching. His first sermon was a printed one which he had memorized for the occasion. He had but little liberty in preaching it. The second time he preached extemporaneously and had some degree of liberty. "I now preached frequently," says he, "both in the churches of the villages and towns, but never had any enjoyment in doing so, except when speaking in a simple way; though the repetition of sermons which had been committed to memory brought more praise from my fellow creatures. But from neither way of preaching did I see any fruit. It may be that the last day will show the benefit even of those feeble endeavors. One reason why the Lord did not permit me to see fruit, seems to me, that I should have been most probably lifted up by success. It may be also because I prayed exceedingly little respecting the ministry of the Word, and because I walked so little with God, and was so rarely a vessel unto honor, sanctified and meet for the Master's use."

The true believers at the University increased from six to about twenty in number before Muller left. They often met in Muller's room to pray, sing and read the Bible. He sometimes walked ten or fifteen miles to hear a really pious minister preach.

In 1827 Muller volunteered to go as a missionary pastor to the Germans at Bucharest, but the war between the Turks and Russians prevented this. In 1828, at the suggestion of their agent, he offered himself to the London Missionary Society as a missionary to the Jews. He was well versed in the Hebrew language and had a great love for it. The Society desired him to come to London that they might see him personally. Through the providence of God he finally secured exemption for life from serving in the Prussian army, and he went to England in 1829, at twenty-four years of age. He was not able to speak the English language for some time after he landed in England and then only in a very broken manner at first.

Soon after coming to England Muller received a deeper Christian experience which entirely revolutionized his life. "I came weak in body to England." says he, "and in consequence of much study, as I suppose, I was taken ill on May 15, and was soon, at least in my own estimation, apparently beyond recovery. The weaker I got in body, the happier I was in spirit. Never in my whole life had I seen myself so vile, so guilty, so altogether what I ought not to have been, as at that time. It was as if every sin of which I had been guilty was brought to my remembrance; but at the same time I could realize that all my sins were completely forgiven -- that I was washed and made clean, completely clean, in the blood of Jesus. The result of this was great peace. I longed exceedingly to depart and to be with Christ..."

"After I had been ill about a fortnight my medical attendant unexpectedly pronounced me better. This, instead of giving me joy, bowed me down, so great was my desire to be with the Lord; though almost immediately afterwards grace was given me to submit myself to the will of God."

That Muller always regarded the above experience as one which deepened his whole spiritual life is clearly shown by a letter of his which appeared in the British Christian, of August 14, 1902. In this letter Muller says: "I became a believer in the Lord Jesus in the beginning of November, 1825, now sixty-nine years and eight months. For the first four years afterwards, it was for a good part in great weakness; but in July, 1829, now sixty-six years since, it came with me to an entire and full surrender of heart. I gave myself fully to the Lord. Honors, pleasures, money, my physical powers, my mental powers, all were laid down at the feet of Jesus, and I became a great lover of the Word of God. I found my all in God, and thus in all my trials of a temporal and spiritual character, it has remained for sixty-six years. My faith is not merely exercised regarding temporal things, but regarding everything, because I cleave to the Word. My knowledge of God and His Word is that which helps me."

Being advised to go into the country for his health, he prayed about it and finally decided to go. He went to Devonshire, where the great blessing he had already received was greatly augmented by his conversations and prayers with a Spirit-filled minister whom he first heard preach at Teignmouth. Through the conversations and sermons of this minister he was led to see as never before "that the Word of God alone is our standard of judgment in spiritual things; that it can be explained only by His Holy Spirit; and that in our day, as well as in former times, He is the teacher of His people. The office of the Holy Spirit I had not experimentally understood before that time," says he. "The result of this was, that the first evening that I shut myself into my room to give myself to prayer and meditation over the Scriptures, I learned more in a few hours than I had done during a period of several months previously." Again, he says: "In addition to these truths, it pleased the Lord to lead me to see a higher standard of devotedness than I had seen before."

On his return to London, Muller sought to lead his brethren in the training seminary into the deeper truths he had been brought to realize. "One brother in particular," says he, "was brought into the same state in which I was; and others, I trust, were more or less benefited. Several times, when I went to my room after family prayer, I found communion with God so sweet that I continued in prayer until after twelve, and then being full of joy, went into the room of the brother just referred to, and finding him also in a similar frame of heart, we continued praying until one or two, and even then I was a few times so full of joy that I could scarcely sleep, and at six in the morning again called the brethren together for prayer."

Muller's health declined in London and his soul was also now on fire for God in such a way that he could not settle down to the routine of daily studies. His newly acquired belief in the near coming of Christ also urged him forward to work for the salvation of souls. He felt that the Lord was leading him to begin at once the Christian work he was longing to do, and as the London Missionary Society did not see proper to send him out without the prescribed course of training, he decided to go at once and trust the Lord for the means of support. Soon after this he became pastor of Ebenezer Chapel, Teignmouth, Devonshire. His marriage to Miss Mary Groves, a Devonshire lady, followed. She was always of the same mind as her husband and their married life was a very happy one. Not long after his marriage he began to have conscientious scruples about receiving a regular salary, and also about the renting of pews in his church. He felt that the latter was giving the "man with the ring on his finger" the best seat, and the poorer brother the footstool, and the former was taking money from those who did not give "cheerfully" or "as the Lord had prospered them." These two customs were discontinued by him. He and his wife told their needs to no one but the Lord. Occasionally reports were spread that they were starving; but though at times their faith was tried, their income was greater than before. He and his wife gave away freely all that they had above their present needs, and trusted the Lord for their "daily bread."

Muller preached in many surrounding towns, and many souls were brought to Christ in his meetings. In 1832 he felt profoundly impressed that, his work was ended in Teignmouth, and when he went to Bristol the same year he was as profoundly impressed that the Lord would have him work there. When the Spirit, the Word, and the providence of God agree, we may be quite certain that the Lord is leading us, for these three are always in harmony and cannot disagree. Not only did Muller feel led of the Lord to work in Bristol, but the providence of God opened the way, and it seemed in harmony with the Word of God.

Muller began his labors in Bristol in 1832, as co-pastor with his friend Mr. Craik, who had been called to that city. Without salaries or rented pews their labors were greatly blessed at Gideon and Bethesda Chapels. The membership more than quadrupled in numbers in a short time. Ten days after the opening of Bethesda there was such a crowd of persons inquiring the way of salvation that it took four hours to minister to them. Subsequently Gideon Chapel was relinquished, and in the course of time two neighboring chapels were secured. These churches, though calling themselves non-sectarian, were usually classed with the people commonly known as "Plymouth Brethren." Muller continued to preach to them as long as he lived, even after he began his great work for the orphans. At the time of his death he had a congregation of about two thousand persons at Bethesda Chapel.

In 1834 Mr. Muller started the Scripture Knowledge Institution for Home and Abroad. Its object was to aid Christian day-schools, to assist missionaries, and to circulate the Scriptures. This institution, without worldly patronage, without asking anyone for help, without contracting debts; without committees, subscribers, or memberships; but through faith in the Lord alone, had obtained and disbursed no less a sum than £1,500,000 ($7,500,000) at the time of Mr. Muller's death. The bulk of this was expended for the orphanage. At the time of Mr. Muller's death 122,000 persons had been taught in the schools supported by these funds; and about 282,000 Bibles and 1,500,000 Testaments had been distributed by means of the same fund. Also 112,000,000 religious books, pamphlets and tracts had been circulated; missionaries had been aided in all parts of the world; and no less than ten thousand orphans had been cared for by means of this same fund.

At the age of seventy, Mr. Muller began to make great evangelistic tours. He traveled 200,000 miles, going around the world and preaching in many lands and in several different languages. He frequently spoke to as many as 4,500 or 5,000 persons. Three times he preached throughout the length and breadth of the United States. He continued his missionary or evangelistic tours until he was ninety years of age. He estimated that during these seventeen years of evangelistic work he addressed three million people. All his expenses were sent in answer to the prayer of faith.

Greatest of all Muller's undertakings was the erection and maintenance of the great orphanages at Bristol. He began the undertaking with only two shillings (50 cents) in his pocket; but in answer to prayer and without making his needs known to human beings, he received the means necessary to erect the great buildings and to feed the orphans day by day for sixty years. In all that time the children did not have to go without a meal, and Mr. Muller said that if they ever had to go without a meal he would take it as evidence that the Lord did not will the work to continue. Sometimes the meal time was almost at hand and they did not know where the food would come from, but the Lord always sent it in due time, during the twenty thousand or more days that Mr. Muller had charge of the homes.

From Deeper Experiences of Famous Christians... by J. Gilchrist Lawson. Anderson, Ind.: Warner Press, 1911.

Among the greatest monuments of what can be accomplished through simple faith in God are the great orphanages covering thirteen acres of ground on Ashley Downs, Bristol, England. When God put it into the heart of George Muller to build these orphanages, he had only two shillings (50 cents) in his pocket. Without making his wants known to any man, but to God alone, over a million, four hundred thousand pounds ($7,000,000) were sent to him for the building and maintaining of these orphan homes. When the writer first visited them, near the time of Mr. Muller's death, there were five immense buildings of solid granite, capable of accommodating two thousand orphans. In all the years since the first orphans arrived the Lord had sent food in due time, so that they had never missed a meal for want of food.

Although George Muller became famous as one of the greatest men of prayer known to history, he was not always a saint. He wandered very deep into sin before he was brought to Christ. He was born in the kingdom of Prussia, in 1805. His father was a revenue collector for the government, and was a worldly-minded man. He supplied George and his brother with plenty of money when they were boys, and they spent it very foolishly. George deceived his father about how much money he spent, and also as to how he spent it. He also stole the government money during his father's absence.

At ten years of age, George was sent to the cathedral classical school at Halberstadt. His father wanted to make a Lutheran clergyman of him, not that he might serve God, but that he might have an easy and comfortable living from the State Church. "My time," says he. "was now spent in studying, reading novels, and indulging, though so young, in sinful practices. Thus it continued until I was fourteen years old, when my mother was suddenly removed. The night she was dying, I, not knowing of her illness, was playing cards until two in the morning, and on the next day, being the Lord's day, I went with some of my companions in sin to a tavern, and then, being filled with strong beer, we went about the streets half intoxicated."

"I grew worse and worse," says he. "Three or four days before I was confirmed (and thus admitted to partake of the Lord's supper), I was guilty of gross immorality; and the very day before my confirmation, when I was in the vestry with the clergyman to confess my sins (according to the usual practice), after a formal manner, I defrauded him; for I handed over to him only a twelfth part of the fee which my father had given me for him."

A few solemn thoughts and desires to lead a better life came to him, but he continued to plunge deeper and deeper into sin. Lying, stealing, gambling, novel-reading, licentiousness, extravagance, and almost every form of sin was indulged in by him. No one would have imagined that the sinful youth would ever become eminent for his faith in God and for his power in prayer. He robbed his father of certain rents which his father had entrusted him to collect, falsifying the accounts of what he had received and pocketing the balance. His money was spent on sinful pleasures, and once he was reduced to such poverty that, in order to satisfy his hunger, he stole a piece of coarse bread, the allowance of a soldier who was quartered in the house where he was. In 1821 he set off on an excursion to Magdeburg, where he spent six days in "much sin." He then went to Brunswick, and put up at an expensive hotel until his money was exhausted. He then put up at a fine hotel in a neighboring village, intending to defraud the hotel-keeper. But his best clothes were taken in lieu of what he owed. He then walked six miles to another inn, where he was arrested for trying to defraud the landlord. He was imprisoned for this crime when sixteen years of age.

After his imprisonment young Muller returned to his home and received a severe thrashing from his angry father. He remained as sinful in heart as ever, but in order to regain his father's confidence he began to lead a very exemplary life outwardly, until he had the confidence of all around him. His father decided to send him to the classical school at Halle, where the discipline was very strict, but George had no intention of going there. He went to Nordhausen instead, and by using many lies and entreaties persuaded his father to allow him to remain there for two years and six months, till Easter, 1825. Here he studied diligently, was held up as an example to the other students, and became proficient in Latin, French, History, and his own language (German). "But whilst I was outwardly gaining the esteem of my fellow-creatures," says he, "I did not care in the least about God, but lived secretly in much sin, in consequence of which I was taken ill, and for thirteen weeks confined to my room. All this time I had no real sorrow of heart, yet being under certain natural impressions of religion, I read through Klopstock's works, without weariness. I cared nothing about the Word of God."

"Now and then I felt I ought to become a different person," says he, "and I tried to amend my conduct, particularly when I went to the Lord's supper, as I used to do twice every year, with the other young men. The day previous to attending that ordinance I used to refrain from certain things, and on the day itself I was serious, and also swore once or twice to God with the emblem of the broken body in my mouth, to become better, thinking that for the oath's sake I should be induced to reform. But after one or two days were over, all was forgotten, and I was as bad as before."

He entered the University of Halle as a divinity student, with good testimonials. This qualified him to preach in the Lutheran state church. While at the university he spent all his money in profligate living. "When my money was spent," says he, "I pawned my watch and part of my linen and clothes, or borrowed in other ways. Yet in the midst of all this I had a desire to renounce this wretched life, for I had no enjoyment in it, and had sense enough left to see, that the end one day or other would be miserable; for I should never get a living. But I had no sorrow of heart on account of offending God."

At the University he formed the acquaintance of a miserable backslider, named Beta, who was trying by means of worldly pleasures to drown out his conviction of sin. They plunged into sin together, and in June, 1825, George was again taken sick. After his recovery they forged letters purporting to be from his parents. With these they obtained passports and set out to see Switzerland. Muller stole from the friends who accompanied him and the journey did not cost him so much as it did them. They returned home to finish up the vacation and then went back to the University, Muller having lied to his father about the trip to Switzerland.

At the University of Halle there were about nine hundred divinity students. All of these were allowed to preach, but Muller estimates that not nine of them feared the Lord. "One Saturday afternoon, about the middle of November, 1825," says he, "I had taken a walk with my friend Beta. On our return he said to me, that he was in the habit of going on Saturday evenings to the house of a Christian, where there was a meeting. On further inquiry he told me that they read the Bible, sang, prayed, and read a printed sermon. No sooner had I heard this, but it was to me as if I had found something after which I had been seeking all my life long. I immediately wished to go with my friend, who was not at once willing to take me; for knowing me as a merry young man, he thought I should not like this meeting. At last, however, he said he would call for me."

Describing the meeting, Muller said: "We went together in the evening. As I did not know the manners of the brethren, and the joy they have in seeing poor sinners, even in any measure caring about the things of God, I made an apology for coming. The kind answer of this dear brother I shall never forget. He said: 'Come as often as you please; house and heart are open to you."' After a hymn was sung they fell upon their knees, and a brother, named Kayser, who afterwards became a missionary to Africa, asked God's blessing on the meeting. "This kneeling down made a deep impression upon me," says Muller, "for I had never either seen any one on his knees, nor had I ever myself prayed on my knees. He then read a chapter and a printed sermon; for no regular meetings for expounding the Scriptures were allowed in Prussia, except an ordained clergyman was present. At the close we sang another hymn, and then the master of the house prayed." The meeting made a deep impression upon Muller. "I was happy," says he, "though if I had been asked why I was happy, I could not clearly have explained it."

"When we walked home, I said to Beta, all we have seen on our journey to Switzerland, and all our former pleasures, are as nothing in comparison with this evening. Whether I fell on my knees when I returned home I do not remember; but this I know, that I lay peaceful and happy in my bed. This shows that the Lord may begin his work in different ways. For I have not the least doubt that on that evening He began a work of grace in me, though I obtained joy without any deep sorrow of heart, and with scarcely any knowledge. But that evening was the turning point in my life. The next day, and Monday, and once or twice besides, I went again to the house of this brother, where I read the Scriptures with him and another brother; for it was too long for me to wait until Saturday came again."

"Now my life became very different, though not so, that my sins were all given up at once. My wicked companions were given up; the going to taverns was discontinued; the habitual practice of telling falsehoods was no longer indulged in, but still a few times more I spoke an untruth... I now no longer lived habitually in sin, though I was still often overcome and sometimes even by open sins, though far less frequently than before, and not without sorrow of heart. I read the Scriptures, prayed often, loved the brethren, went to church from right motives and stood on the side of Christ, though laughed at by my fellow students."

For a few weeks after his conversion Muller made rapid advancement in the Christian life, and he was greatly desirous of becoming a missionary. But he fell in love with a Roman Catholic girl, and for some time the Lord was well nigh forgotten. Then Muller saw a young missionary giving up all the luxuries of a beautiful home for Christ. This opened his eyes to his own selfishness and enabled him to give up the girl who had taken the place of Christ in his heart. "It was at this time," says he, "that I began to enjoy the peace of God, which passeth all understanding. In this my joy I wrote to my father and brother, entreating them to seek the Lord, and telling them how happy I was; thinking, that if the way to happiness were set before them, they would gladly embrace it. To my great surprise an angry answer was returned."

George could not enter any German missionary training institution without the consent of his father, and this he could not obtain. His father was deeply grieved that after educating him so that he could obtain a comfortable living as a clergyman he should turn missionary. George felt that he could no longer accept any money from him. The Lord graciously sent him means with which to complete his education. He taught German to some American college professors at the University, and they handsomely remunerated him for his services. He was now the means of winning a number of souls to Christ. He gave away thousands of religious tracts and papers, and spoke to many persons concerning the salvation of their souls.

Although, before his conversion, Muller had written to his father and told him about sermons he had preached, he never really preached a sermon until some time after his conversion. He thought to please his father by making him believe that he was preaching. His first sermon was a printed one which he had memorized for the occasion. He had but little liberty in preaching it. The second time he preached extemporaneously and had some degree of liberty. "I now preached frequently," says he, "both in the churches of the villages and towns, but never had any enjoyment in doing so, except when speaking in a simple way; though the repetition of sermons which had been committed to memory brought more praise from my fellow creatures. But from neither way of preaching did I see any fruit. It may be that the last day will show the benefit even of those feeble endeavors. One reason why the Lord did not permit me to see fruit, seems to me, that I should have been most probably lifted up by success. It may be also because I prayed exceedingly little respecting the ministry of the Word, and because I walked so little with God, and was so rarely a vessel unto honor, sanctified and meet for the Master's use."

The true believers at the University increased from six to about twenty in number before Muller left. They often met in Muller's room to pray, sing and read the Bible. He sometimes walked ten or fifteen miles to hear a really pious minister preach.

In 1827 Muller volunteered to go as a missionary pastor to the Germans at Bucharest, but the war between the Turks and Russians prevented this. In 1828, at the suggestion of their agent, he offered himself to the London Missionary Society as a missionary to the Jews. He was well versed in the Hebrew language and had a great love for it. The Society desired him to come to London that they might see him personally. Through the providence of God he finally secured exemption for life from serving in the Prussian army, and he went to England in 1829, at twenty-four years of age. He was not able to speak the English language for some time after he landed in England and then only in a very broken manner at first.

Soon after coming to England Muller received a deeper Christian experience which entirely revolutionized his life. "I came weak in body to England." says he, "and in consequence of much study, as I suppose, I was taken ill on May 15, and was soon, at least in my own estimation, apparently beyond recovery. The weaker I got in body, the happier I was in spirit. Never in my whole life had I seen myself so vile, so guilty, so altogether what I ought not to have been, as at that time. It was as if every sin of which I had been guilty was brought to my remembrance; but at the same time I could realize that all my sins were completely forgiven -- that I was washed and made clean, completely clean, in the blood of Jesus. The result of this was great peace. I longed exceedingly to depart and to be with Christ..."

"After I had been ill about a fortnight my medical attendant unexpectedly pronounced me better. This, instead of giving me joy, bowed me down, so great was my desire to be with the Lord; though almost immediately afterwards grace was given me to submit myself to the will of God."

That Muller always regarded the above experience as one which deepened his whole spiritual life is clearly shown by a letter of his which appeared in the British Christian, of August 14, 1902. In this letter Muller says: "I became a believer in the Lord Jesus in the beginning of November, 1825, now sixty-nine years and eight months. For the first four years afterwards, it was for a good part in great weakness; but in July, 1829, now sixty-six years since, it came with me to an entire and full surrender of heart. I gave myself fully to the Lord. Honors, pleasures, money, my physical powers, my mental powers, all were laid down at the feet of Jesus, and I became a great lover of the Word of God. I found my all in God, and thus in all my trials of a temporal and spiritual character, it has remained for sixty-six years. My faith is not merely exercised regarding temporal things, but regarding everything, because I cleave to the Word. My knowledge of God and His Word is that which helps me."

Being advised to go into the country for his health, he prayed about it and finally decided to go. He went to Devonshire, where the great blessing he had already received was greatly augmented by his conversations and prayers with a Spirit-filled minister whom he first heard preach at Teignmouth. Through the conversations and sermons of this minister he was led to see as never before "that the Word of God alone is our standard of judgment in spiritual things; that it can be explained only by His Holy Spirit; and that in our day, as well as in former times, He is the teacher of His people. The office of the Holy Spirit I had not experimentally understood before that time," says he. "The result of this was, that the first evening that I shut myself into my room to give myself to prayer and meditation over the Scriptures, I learned more in a few hours than I had done during a period of several months previously." Again, he says: "In addition to these truths, it pleased the Lord to lead me to see a higher standard of devotedness than I had seen before."

On his return to London, Muller sought to lead his brethren in the training seminary into the deeper truths he had been brought to realize. "One brother in particular," says he, "was brought into the same state in which I was; and others, I trust, were more or less benefited. Several times, when I went to my room after family prayer, I found communion with God so sweet that I continued in prayer until after twelve, and then being full of joy, went into the room of the brother just referred to, and finding him also in a similar frame of heart, we continued praying until one or two, and even then I was a few times so full of joy that I could scarcely sleep, and at six in the morning again called the brethren together for prayer."

Muller's health declined in London and his soul was also now on fire for God in such a way that he could not settle down to the routine of daily studies. His newly acquired belief in the near coming of Christ also urged him forward to work for the salvation of souls. He felt that the Lord was leading him to begin at once the Christian work he was longing to do, and as the London Missionary Society did not see proper to send him out without the prescribed course of training, he decided to go at once and trust the Lord for the means of support. Soon after this he became pastor of Ebenezer Chapel, Teignmouth, Devonshire. His marriage to Miss Mary Groves, a Devonshire lady, followed. She was always of the same mind as her husband and their married life was a very happy one. Not long after his marriage he began to have conscientious scruples about receiving a regular salary, and also about the renting of pews in his church. He felt that the latter was giving the "man with the ring on his finger" the best seat, and the poorer brother the footstool, and the former was taking money from those who did not give "cheerfully" or "as the Lord had prospered them." These two customs were discontinued by him. He and his wife told their needs to no one but the Lord. Occasionally reports were spread that they were starving; but though at times their faith was tried, their income was greater than before. He and his wife gave away freely all that they had above their present needs, and trusted the Lord for their "daily bread."

Muller preached in many surrounding towns, and many souls were brought to Christ in his meetings. In 1832 he felt profoundly impressed that, his work was ended in Teignmouth, and when he went to Bristol the same year he was as profoundly impressed that the Lord would have him work there. When the Spirit, the Word, and the providence of God agree, we may be quite certain that the Lord is leading us, for these three are always in harmony and cannot disagree. Not only did Muller feel led of the Lord to work in Bristol, but the providence of God opened the way, and it seemed in harmony with the Word of God.

Muller began his labors in Bristol in 1832, as co-pastor with his friend Mr. Craik, who had been called to that city. Without salaries or rented pews their labors were greatly blessed at Gideon and Bethesda Chapels. The membership more than quadrupled in numbers in a short time. Ten days after the opening of Bethesda there was such a crowd of persons inquiring the way of salvation that it took four hours to minister to them. Subsequently Gideon Chapel was relinquished, and in the course of time two neighboring chapels were secured. These churches, though calling themselves non-sectarian, were usually classed with the people commonly known as "Plymouth Brethren." Muller continued to preach to them as long as he lived, even after he began his great work for the orphans. At the time of his death he had a congregation of about two thousand persons at Bethesda Chapel.

In 1834 Mr. Muller started the Scripture Knowledge Institution for Home and Abroad. Its object was to aid Christian day-schools, to assist missionaries, and to circulate the Scriptures. This institution, without worldly patronage, without asking anyone for help, without contracting debts; without committees, subscribers, or memberships; but through faith in the Lord alone, had obtained and disbursed no less a sum than £1,500,000 ($7,500,000) at the time of Mr. Muller's death. The bulk of this was expended for the orphanage. At the time of Mr. Muller's death 122,000 persons had been taught in the schools supported by these funds; and about 282,000 Bibles and 1,500,000 Testaments had been distributed by means of the same fund. Also 112,000,000 religious books, pamphlets and tracts had been circulated; missionaries had been aided in all parts of the world; and no less than ten thousand orphans had been cared for by means of this same fund.

At the age of seventy, Mr. Muller began to make great evangelistic tours. He traveled 200,000 miles, going around the world and preaching in many lands and in several different languages. He frequently spoke to as many as 4,500 or 5,000 persons. Three times he preached throughout the length and breadth of the United States. He continued his missionary or evangelistic tours until he was ninety years of age. He estimated that during these seventeen years of evangelistic work he addressed three million people. All his expenses were sent in answer to the prayer of faith.

Greatest of all Muller's undertakings was the erection and maintenance of the great orphanages at Bristol. He began the undertaking with only two shillings (50 cents) in his pocket; but in answer to prayer and without making his needs known to human beings, he received the means necessary to erect the great buildings and to feed the orphans day by day for sixty years. In all that time the children did not have to go without a meal, and Mr. Muller said that if they ever had to go without a meal he would take it as evidence that the Lord did not will the work to continue. Sometimes the meal time was almost at hand and they did not know where the food would come from, but the Lord always sent it in due time, during the twenty thousand or more days that Mr. Muller had charge of the homes.

From Deeper Experiences of Famous Christians... by J. Gilchrist Lawson. Anderson, Ind.: Warner Press, 1911.

The Story of John Bunyan's ‘Pilgrim's Progress’

On the morning of November 12, 1660, a young pastor entered a small meeting house in Lower Samsell, England, preparing to be arrested. He hadn’t noticed the men keeping guard outside the house, but he didn’t need to. A friend had warned him that they were coming. He came anyway. He had agreed to preach. The constable broke in upon the meeting and began searching the faces until he found the one he came for: a tall man, wearing a reddish mustache and plain clothes, paused in the act of prayer. John Bunyan by name. “Had I been minded to play the coward, I could have escaped,” Bunyan later remembered. But he had no mind for that now. He spoke what closing exhortation he could as the constable forced him from the house, a man with no weapon but his Bible. Two months and several court proceedings later, Bunyan was taken from his church, his family, and his job to serve “one of the longest jail terms . . . by a dissenter in England” (On Reading Well, 182). For twelve years, he would sleep on a straw mat in a cold cell. For twelve years, he would wake up away from his wife and four young children. For twelve years, he would wait for release or, if not, exile or execution. And in those twelve years, he began a book about a pilgrim named Christian — a book that would become, for over two centuries, the best-selling book written in the English language. Tinker Turned Preacher John Bunyan (1628–1688) was not the most likely Englishman to write The Pilgrim’s Progress, a book that would be translated into two hundred languages, that would capture the imaginations of children and scholars alike, and that would rank, in influence and popularity, just behind the King James Bible in the English-speaking world. “Bunyan is the first major English writer who was neither London-based nor university-educated,” writes Christopher Hill. Rather, “the army had been his school, and prison his university” (The Life, Books, and Influence of John Bunyan, 168). “‘Pilgrim’s Progress’ bears the marks of John Bunyan’s confinement. Without the prison, we may not have the pilgrim.” As Paul said of the Corinthians, so we might say of Bunyan: he had few advantages “according to worldly standards” (1 Corinthians 1:26). In his spiritual autobiography, Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners, he confesses that his father’s house was “of that rank that is meanest and most despised of all the families in the land” (7). Thomas Bunyan was a tinker, a traveling mender of pots, pans, and other metal utensils. Thomas sent his son to school only briefly, where John learned to read and write. Later, after a stint in the army, he followed his father into the tinker trade. Meanwhile, Bunyan recalls, “I had but few equals, especially considering my years, which were tender, being few, both for cursing, swearing, lying, and blaspheming the name of God” (Grace Abounding, 8). Sometime in Bunyan’s early twenties, however, God laid his hand on the blasphemous tinker and began to press. For the first time, Bunyan felt the load of sin and guilt on his back, and despair nearly sunk him. He agonized over his soul for years before he was finally able to say, “Great sins do draw out great grace; and where guilt is most terrible and fierce, there the mercy of God in Christ, when showed to the soul, appears most high and mighty” (Grace Abounding, 97). Bunyan soon carried this travail and triumph of grace into the pulpit of a Bedford church, where he heralded Christ so powerfully that congregations throughout Bedfordshire County began asking for the tinker turned preacher — including a small gathering of believers in Lower Samsell. Trying Days for Dissenters Not everyone in England responded warmly to Bunyan’s preaching, however. “He lived in more trying days than those in which our lot is fallen,” wrote John Newton a century later (“Preface to The Pilgrim’s Progress,” xxxix). Yes, these were trying days — at least for dissenting pastors like Bunyan, who refused to join the Church of England. Throughout the seventeenth century, dissenters were sometimes honored, sometimes ignored, and sometimes arrested by England’s authorities. Bunyan’s lot fell into the last of these. Some dissenters did not exactly help the cause. A Puritan sect called the Fifth Monarchy Men, for example, took to arms in 1657 and 1661 in order to claim England’s crown for the (supposedly) soon-to-return Christ. Often, then, “the authorities did not seek to suppress Dissenters as heretics but as disturbers of law and order,” David Calhoun explains (Life, Books, and Influence, 28). Bunyan was no radical — simply a tinker who preached without an official license. Still, the Bedfordshire authorities thought it safer to silence him. Once arrested, Bunyan was given an ultimatum: If he would agree to cease preaching and remain quiet in his calling as a tinker, he could return to his family at once. If he refused, imprisonment and potential exile awaited him. At one point in the proceedings (which lasted several weeks), Bunyan responded, If any man can lay anything to my charge, either in doctrine or practice, in this particular, that can be proved error or heresy, I am willing to disown it, even in the very market place; but if it be truth, then to stand to it to the last drop of my blood. (Grace Abounding, 153) Bunyan was then 32 years old. He would not be a free man again until age 44. Bedford Jail Despite Bunyan’s boldness before the magistrates, his decision was not an easy one. Most trying of all was his separation from Elizabeth, his wife, and their four young children, one of whom was blind. Years into his jail time, he would write, “The parting with my wife and poor children has oft been to me in this place as the pulling the flesh from my bones” (Grace Abounding, 122). He would make shoelaces over the next twelve years to help support them. But Bunyan would not ultimately regret his decision. Though parted from the comfort of his family, he was not parted from the comfort of his Master. “Jesus Christ . . . was never more real and apparent than now,” the imprisoned Bunyan wrote. “Here I have seen him and felt him indeed” (Grace Abounding, 119). “The best designs of the devil can only serve the progress of God’s pilgrims.” With comfort in his soul, then, Bunyan gave himself to whatever ministry he could. He counseled visitors. He and other inmates preached to each other on Sundays. But most of all, Bunyan wrote. In jail, with his Bible and Foxe’s Book of Martyrs close at hand, he penned Grace Abounding. There also, as he was working on another book, an image of a path and a pilgrim flashed upon his mind. “And thus it was,” Bunyan wrote in a poem, I, writing of the way And race of saints, in this our gospel day, Fell suddenly into an allegory, About their journey, and the way to glory. (Pilgrim’s Progress, 3) Thus began the book that would soon be read, not only in Bunyan’s Bedford, but in Sheffield, Birmingham, Manchester, London — and eventually far beyond. The Bedford magistrates sought to silence Bunyan in jail. In jail, Bunyan sounded a trumpet that reached the ears of all the West, and even the world. Calvinism in Delightful Colors The genius of Bunyan’s book, along with its immediate popularity, owes much to the writer’s sudden fall “into an allegory.” As an allegory, Pilgrim’s Progress operates on two levels. On one level, the book is a storehouse of Puritan theology — “the Westminster Confession of Faith with people in it,” as someone once said. On another level, however, it is an enthralling adventure story — a journey of life and death from the City of Destruction to the Celestial City. The poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge would later write, “I could not have believed beforehand that Calvinism could be painted in such exquisitely delightful colors” (Life, Books, and Influence, 166). Those who read Pilgrim’s Progress find theology coming to them in dungeons and caves, in sword fights and fairs, in honest friends and two-faced flatterers. Bunyan does not merely tell us we must renounce all for Christ’s sake; he shows us Christian fleeing his neighbors and family, fingers in his ears, crying, “Life! life! eternal life!” (Pilgrim’s Progress, 14). Bunyan does not simply instruct us about our spiritual conflict; he makes us stand in the Valley of Humiliation with a “foul fiend . . . hideous to behold” striding toward us (66). Bunyan does not just warn us of the subtlety of temptation; he gives us sore feet on a rocky path, and then reveals a smooth road “on the other side of the fence” (129) — more comfortable on the feet, but the straightest way to a giant named Despair. The cast of characters in Pilgrim’s Progress reminds us that the path to the Celestial City is narrow — so narrow that only a few find it, while scores fall by the wayside. Here we meet Timorous, who flees backward at the sight of lions; Mr. Hold-the-world, who falls into Demas’s cave; Talkative, whose religion lives only in his tongue; Ignorance, who seeks entrance to the city by his own merits; and a host of others who, for one reason or another, do not endure to the end. “In jail, John Bunyan sounded a trumpet that reached the ears of all the West, and even the world.” And herein lies the drama of the story. Bunyan, a staunch believer in the doctrine of the saints’ perseverance, nevertheless refused to take that perseverance for granted. As long as we are on the path, we are “not yet out of the gun-shot of the devil” (101). Between here and our home, many enemies lie along the way. Nevertheless, let every pilgrim take courage: “you have all power in heaven and earth on your side” (101). If grace has brought us to the path, grace will guard our every step. ‘All We Do Is Succeed’ Within ten years of its publishing date in 1678, Pilgrim’s Progress had gone through eleven editions and made the Bedford tinker a national phenomenon. According to Calhoun, “Some three thousand people came to hear him one Sunday in London, and twelve hundred turned up for a weekday sermon during the winter” (Life, Books, and Influence, 38). If the Bedford magistrates had allowed Bunyan to continue preaching, we would still remember him today as the author of several dozen books and as one of the many Puritan luminaries. But in all likelihood, he would not be read today in some two hundred languages besides his own. For Pilgrim’s Progress is a work of prison literature — and it bears the marks of Bunyan’s confinement. Without the prison, we would likely not have the pilgrim. The story of Bunyan and his book, then, is yet one more illustration that God’s ways are high above our own (Isaiah 55:8–9), and that the best designs of the devil can only serve the progress of God’s pilgrims (Genesis 50:20). John Piper, reflecting on Bunyan’s imprisonment, says, “All we do is succeed — either painfully or pleasantly” (“The Chief Design of My Life”). Yes, if we have lost our burden at the cross, and now find ourselves on the pilgrims’ path, all we do is succeed. We succeed whether we feast with the saints in Palace Beautiful or wrestle Apollyon in the Valley of Humiliation. We succeed whether we fellowship with shepherds in the Delectable Mountains or lie bleeding in Vanity Fair. We succeed even when we walk straight into the last river, our feet reaching for the bottom as the water rises above our heads. For at the end of this path is a prince who “is such a lover of poor pilgrims, that the like is not to be found from the east to the west” (Pilgrim’s Progress, 61). Among the company of that prince is one John Bunyan, a pilgrim who has now joined the cloud of witnesses (Hebrews 12:1). “Though he died, he still speaks” (Hebrews 11:4) — and urges the rest of us onward. Article by Scott Hubbard

-480.webp)