Ten Lies People Believe About Money Order Printed Copy

- Author: Mike Murdock

- Size: 870KB | 48 pages

- |

Others like ten lies people believe about money Features >>

31 Reasons People Do Not Receive Their Financial Harvest

The Miracle Of Debt Release

-160.webp)

Money Won't Make You Rich (God's Principles For True Wealth, Prosperity, And Success)

From Rats To Riches

Do You Fit The Profile Of A Prosperous Believer?

Frugality

The Financial Peace Planner

I'll Never Be Broke Another Day

No More Debt

The Covenant Of Wealth

About the Book

"Ten Lies People Believe About Money" by Mike Murdock explores common misconceptions surrounding money and finances, such as the belief that money is evil or that wealth is unattainable. The book offers practical advice and biblical principles to help readers overcome these false beliefs and achieve financial success.

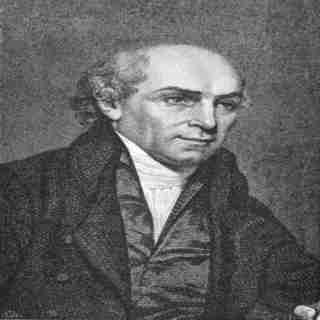

William Carey

"Expect great things; attempt great things."

At a meeting of Baptist leaders in the late 1700s, a newly ordained minister stood to argue for the value of overseas missions. He was abruptly interrupted by an older minister who said, "Young man, sit down! You are an enthusiast. When God pleases to convert the heathen, he'll do it without consulting you or me."

That such an attitude is inconceivable today is largely due to the subsequent efforts of that young man, William Carey.

Plodder Carey was raised in the obscure, rural village of Paulerpury, in the middle of England. He apprenticed in a local cobbler's shop, where the nominal Anglican was converted. He enthusiastically took up the faith, and though little educated, the young convert borrowed a Greek grammar and proceeded to teach himself New Testament Greek.

When his master died, he took up shoemaking in nearby Hackleton, where he met and married Dorothy Plackett, who soon gave birth to a daughter. But the apprentice cobbler's life was hard—the child died at age 2—and his pay was insufficient. Carey's family sunk into poverty and stayed there even after he took over the business.

"I can plod," he wrote later, "I can persevere to any definite pursuit." All the while, he continued his language studies, adding Hebrew and Latin, and became a preacher with the Particular Baptists. He also continued pursuing his lifelong interest in international affairs, especially the religious life of other cultures.

Carey was impressed with early Moravian missionaries and was increasingly dismayed at his fellow Protestants' lack of missions interest. In response, he penned An Enquiry into the Obligations of Christians to Use Means for the Conversion of the Heathens. He argued that Jesus' Great Commission applied to all Christians of all times, and he castigated fellow believers of his day for ignoring it: "Multitudes sit at ease and give themselves no concern about the far greater part of their fellow sinners, who to this day, are lost in ignorance and idolatry."

Carey didn't stop there: in 1792 he organized a missionary society, and at its inaugural meeting preached a sermon with the call, "Expect great things from God; attempt great things for God!" Within a year, Carey, John Thomas (a former surgeon), and Carey's family (which now included three boys, and another child on the way) were on a ship headed for India.

Stranger in a strange land

Thomas and Carey had grossly underestimated what it would cost to live in India, and Carey's early years there were miserable. When Thomas deserted the enterprise, Carey was forced to move his family repeatedly as he sought employment that could sustain them. Illness racked the family, and loneliness and regret set it: "I am in a strange land," he wrote, "no Christian friend, a large family, and nothing to supply their wants." But he also retained hope: "Well, I have God, and his word is sure."

He learned Bengali with the help of a pundit, and in a few weeks began translating the Bible into Bengali and preaching to small gatherings.

When Carey himself contracted malaria, and then his 5-year-old Peter died of dysentery, it became too much for his wife, Dorothy, whose mental health deteriorated rapidly. She suffered delusions, accusing Carey of adultery and threatening him with a knife. She eventually had to be confined to a room and physically restrained.

"This is indeed the valley of the shadow of death to me," Carey wrote, though characteristically added, "But I rejoice that I am here notwithstanding; and God is here."

Gift of tongues

In October 1799, things finally turned. He was invited to locate in a Danish settlement in Serampore, near Calcutta. He was now under the protection of the Danes, who permitted him to preach legally (in the British-controlled areas of India, all of Carey's missionary work had been illegal).

Carey was joined by William Ward, a printer, and Joshua and Hanna Marshman, teachers. Mission finances increased considerably as Ward began securing government printing contracts, the Marshmans opened schools for children, and Carey began teaching at Fort William College in Calcutta.

In December 1800, after seven years of missionary labor, Carey baptized his first convert, Krishna Pal, and two months later, he published his first Bengali New Testament. With this and subsequent editions, Carey and his colleagues laid the foundation for the study of modern Bengali, which up to this time had been an "unsettled dialect."

Carey continued to expect great things; over the next 28 years, he and his pundits translated the entire Bible into India's major languages: Bengali, Oriya, Marathi, Hindi, Assamese, and Sanskrit and parts of 209 other languages and dialects.

He also sought social reform in India, including the abolition of infanticide, widow burning (sati), and assisted suicide. He and the Marshmans founded Serampore College in 1818, a divinity school for Indians, which today offers theological and liberal arts education for some 2,500 students.

By the time Carey died, he had spent 41 years in India without a furlough. His mission could count only some 700 converts in a nation of millions, but he had laid an impressive foundation of Bible translations, education, and social reform.

His greatest legacy was in the worldwide missionary movement of the nineteenth century that he inspired. Missionaries like Adoniram Judson, Hudson Taylor, and David Livingstone, among thousands of others, were impressed not only by Carey's example, but by his words "Expect great things; attempt great things." The history of nineteenth-century Protestant missions is in many ways an extended commentary on the phrase.

"Expect great things; attempt great things."

At a meeting of Baptist leaders in the late 1700s, a newly ordained minister stood to argue for the value of overseas missions. He was abruptly interrupted by an older minister who said, "Young man, sit down! You are an enthusiast. When God pleases to convert the heathen, he'll do it without consulting you or me."

That such an attitude is inconceivable today is largely due to the subsequent efforts of that young man, William Carey.

Plodder Carey was raised in the obscure, rural village of Paulerpury, in the middle of England. He apprenticed in a local cobbler's shop, where the nominal Anglican was converted. He enthusiastically took up the faith, and though little educated, the young convert borrowed a Greek grammar and proceeded to teach himself New Testament Greek.

When his master died, he took up shoemaking in nearby Hackleton, where he met and married Dorothy Plackett, who soon gave birth to a daughter. But the apprentice cobbler's life was hard—the child died at age 2—and his pay was insufficient. Carey's family sunk into poverty and stayed there even after he took over the business.

"I can plod," he wrote later, "I can persevere to any definite pursuit." All the while, he continued his language studies, adding Hebrew and Latin, and became a preacher with the Particular Baptists. He also continued pursuing his lifelong interest in international affairs, especially the religious life of other cultures.

Carey was impressed with early Moravian missionaries and was increasingly dismayed at his fellow Protestants' lack of missions interest. In response, he penned An Enquiry into the Obligations of Christians to Use Means for the Conversion of the Heathens. He argued that Jesus' Great Commission applied to all Christians of all times, and he castigated fellow believers of his day for ignoring it: "Multitudes sit at ease and give themselves no concern about the far greater part of their fellow sinners, who to this day, are lost in ignorance and idolatry."

Carey didn't stop there: in 1792 he organized a missionary society, and at its inaugural meeting preached a sermon with the call, "Expect great things from God; attempt great things for God!" Within a year, Carey, John Thomas (a former surgeon), and Carey's family (which now included three boys, and another child on the way) were on a ship headed for India.

Stranger in a strange land

Thomas and Carey had grossly underestimated what it would cost to live in India, and Carey's early years there were miserable. When Thomas deserted the enterprise, Carey was forced to move his family repeatedly as he sought employment that could sustain them. Illness racked the family, and loneliness and regret set it: "I am in a strange land," he wrote, "no Christian friend, a large family, and nothing to supply their wants." But he also retained hope: "Well, I have God, and his word is sure."

He learned Bengali with the help of a pundit, and in a few weeks began translating the Bible into Bengali and preaching to small gatherings.

When Carey himself contracted malaria, and then his 5-year-old Peter died of dysentery, it became too much for his wife, Dorothy, whose mental health deteriorated rapidly. She suffered delusions, accusing Carey of adultery and threatening him with a knife. She eventually had to be confined to a room and physically restrained.

"This is indeed the valley of the shadow of death to me," Carey wrote, though characteristically added, "But I rejoice that I am here notwithstanding; and God is here."

Gift of tongues

In October 1799, things finally turned. He was invited to locate in a Danish settlement in Serampore, near Calcutta. He was now under the protection of the Danes, who permitted him to preach legally (in the British-controlled areas of India, all of Carey's missionary work had been illegal).

Carey was joined by William Ward, a printer, and Joshua and Hanna Marshman, teachers. Mission finances increased considerably as Ward began securing government printing contracts, the Marshmans opened schools for children, and Carey began teaching at Fort William College in Calcutta.

In December 1800, after seven years of missionary labor, Carey baptized his first convert, Krishna Pal, and two months later, he published his first Bengali New Testament. With this and subsequent editions, Carey and his colleagues laid the foundation for the study of modern Bengali, which up to this time had been an "unsettled dialect."

Carey continued to expect great things; over the next 28 years, he and his pundits translated the entire Bible into India's major languages: Bengali, Oriya, Marathi, Hindi, Assamese, and Sanskrit and parts of 209 other languages and dialects.

He also sought social reform in India, including the abolition of infanticide, widow burning (sati), and assisted suicide. He and the Marshmans founded Serampore College in 1818, a divinity school for Indians, which today offers theological and liberal arts education for some 2,500 students.

By the time Carey died, he had spent 41 years in India without a furlough. His mission could count only some 700 converts in a nation of millions, but he had laid an impressive foundation of Bible translations, education, and social reform.

His greatest legacy was in the worldwide missionary movement of the nineteenth century that he inspired. Missionaries like Adoniram Judson, Hudson Taylor, and David Livingstone, among thousands of others, were impressed not only by Carey's example, but by his words "Expect great things; attempt great things." The history of nineteenth-century Protestant missions is in many ways an extended commentary on the phrase.

Satan Will Sing You to Sleep

“You don’t tell people about Jesus, because you don’t care about their eternal state.” His assertion stung. But I knew it was true. Confronted with the way he lives for the lost, its truth was as obvious to me as the nose on my face. And like the nose on my face, I wasn’t paying much attention to it until he called it out. But unlike the nose on my face, his assertion was eternally significant. I recently met this remarkable man while traveling in the Middle East. He, along with his wife, is leading a rapidly growing movement of Muslims turning to Christ in a very restrictive part of the Islamic world. I had the great (and exposing) privilege of spending hours with him. I wish I could tell you more about his story — how Jesus called him and the incredible ways the Lord uniquely prepared him to make disciples and plant churches in a very dangerous place. His story is worth a book someday. For now, I will spare the details, lest I in any way expose him. I must pass along something he shared with me, though, because we all might be ignoring the obvious and eternally significant “nose” on our collective Western Christian faces — to our own spiritual detriment, for sure, but also to the spiritual catastrophe of those around us. What Could Happen to Them My new friend lives in an Islamic country where sharing the gospel, if you’re caught, will get you thrown into prison and likely tortured to extract information about other Christians. Yet he and his wife are daily, diligently seeking to share the gospel with others because they want to “share with them in its blessings” (1 Corinthians 9:23) — even more than they want their own survival. Each morning, when this husband and wife part ways, they acknowledge to one another that it might be the last time they see each other. She knows, if caught, part of her torture will almost assuredly include rape, probably repeatedly. He knows, if caught, brutal things await him before a likely execution. For to them, “to live is Christ, and to die is gain” (Philippians 1:21). Yet each day they prayerfully pursue the Spirit of Jesus’s direction in order to show the lost the way of salvation. And they are equipping other Christians to do the same. Wholly Dependent on God When I say “prayerfully,” I mean prayerfully. They, and their fellow leaders, spend a minimum of four hours a day in prayer and God’s word, and frequently fast for extended periods, before they go out seeking souls. They do this because they need to. Spiritual strongholds do not give way and conversions don’t happen unless they do this. One wrong move and a whole network of believers could be exposed. So, they depend on the Holy Spirit to specifically lead them to people the Spirit has prepared. For them, the doctrine of election is not some abstract theological controversy for seminary students to debate. They see it played out in front of them continually. The cessationism-continuationism debate is also a moot issue for them. They regularly see the Holy Spirit do things we read about in the book of Acts. As my friend described the Spirit’s activity where he lives, it was clear that all the revelatory and miraculous spiritual gifts listed in 1 Corinthians 12–14 are a normal part of life for these believers — because they really need them. They’re not debating Christian Hedonism either. When you live under the threat of death daily, either life is Christ and death is gain to you, or you will not last. So, I learned that my friend has translated John Piper’s original sermon series on Christian Hedonism into his native language and used them as part of his core theological curriculum for believers. Lulled by an Evil Lullaby All those things were wonderful and encouraging — as well as convicting — to hear. But then he told me a disturbing story. A number of years ago, this man and his wife were given the opportunity to move to the States, and they did. After living here for a period of time, however, the wife began to plead with her husband that they move back to their Islamic country of origin. Why? She told him, “It’s like there’s a satanic lullaby playing here, and the Christians are asleep. And I feel like I’m falling asleep! Please, let’s go back!” Which they did (God be praised!). This story contains an urgent message we must hear: she wanted to go back to a dangerous environment to escape what she recognized as a greater danger to her faith: spiritual lethargy and indifference. This should stop us in our tracks. Do we recognize this as a serious danger? How spiritually sleepy are we? According to my new friend, we can gauge our sleepiness by how the eternal states of non-Christians around us shape the way we approach life. Judging by the general behavior of Christians in the West, it’s clear to my friend that, as a whole (we all can point to remarkable exceptions), we don’t care much about people’s eternal states. Are We Content to Sleep? My friend and his wife are right. There is a satanic lullaby playing, even in churches, across the West. Why else are we so lethargic in the midst of such relative freedom and unprecedented prosperity? Where is our collective Christian sense of urgency? Where are the tears over the perishing? Where is the groaning? Where is the fasting and prevailing intercession for those we love and those we live near and those we work with, not to mention the unreached of the world who have no meaningful gospel witness among them? Paul had “great sorrow and unceasing anguish in [his] heart” over his unbelieving Jewish kinsmen (Romans 9:2). Do we feel anything like that? And Paul’s Spirit-inspired urgency to bring the gospel to the lost shaped his whole approach to life: I have become all things to all people, that by all means I might save some. I do it all for the sake of the gospel, that I may share with them in its blessings. (1 Corinthians 9:22–23) What is shaping our approach to life? If we think that kind of mentality was only for someone with Paul’s apostolic calling, all we need to do is keep reading 1 Corinthians 9:24–27. It’s clear that Paul means for us to run our unique faith-races with the same kind of kingdom-focused mentality. If we’re not feeling anguish over people’s eternal state and ordering our lives around praying for and trying to find ways to bring the gospel to them, we are being lulled to sleep by the devil’s soothing strains. It’s time to start fasting and praying and pleading with God and one another to wake up. Now Is the Time It matters not if we call ourselves Calvinists and believe we have an accurate knowledge of the doctrine of election, if our knowledge does not lead us to feel anguish in our hearts over the lost and a resolve to do whatever it takes to save some. “We do not yet know as we ought to know” (to paraphrase 1 Corinthians 8:2). What we need is to cultivate Paul’s heart for the lost. My conversation with this new friend showed me that, Calvinist though I am, I do not yet know as I ought to know. But, Father, I want to know as I ought to know! I repent of all lethargy and indifference! I will not remain sleepy anymore when it comes to the eternal states of the unbelieving family and friends and neighbors and restaurant servers and checkout clerks all around me. Over Our Dead Bodies According to Jesus, in his parable of the ten virgins, spiritual sleepiness is a very, very dangerous condition (Matthew 25:1–13). We need to get more oil — now! There isn’t much time. I want to be done with satanic sleepiness and cultivate the resolve that led Charles Spurgeon — that unashamed Calvinist — to say, If sinners be damned, at least let them leap to hell over our dead bodies. And if they perish, let them perish with our arms wrapped about their knees, imploring them to stay. If hell must be filled, let it be filled in the teeth of our exertions, and let not one go unwarned and unprayed for. Father, in Jesus’s name, increase my anguish over perishing unbelievers and my urgent resolve to “become all things to all people, that by all means I might save some” (1 Corinthians 9:22), whatever it takes! Article by Jon Bloom

-480.webp)