Others like servant leadership Features >>

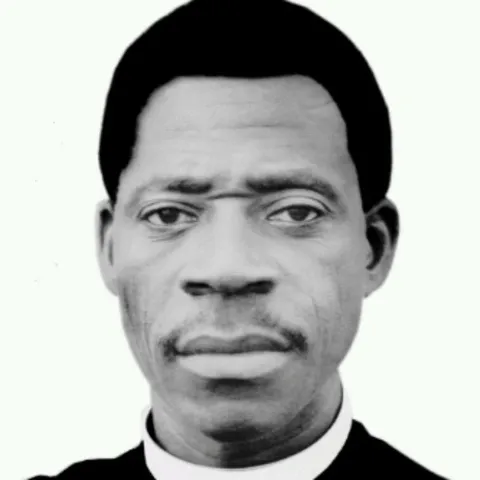

Joseph Ayodele Babalola

His Background

Joseph Ayodele Babalola was born on April 25, 1904 to David Rotimi and Madam Marta Talabi who belonged to the Anglican Church. The family lived at Odo-Owa in Ilofa, a small town about ninety kilometres from Ilorin in Kwara State, Nigeria. His father was the Baba Ijo (“church father”) of the C.M.S. Church at Odo-Owa. Pastor Medayese wrote in his book Itan Igbe dide Woli Ayo Babalola that mysterious circumstances surrounded the birth of Babalola. On that day, it was believed that a strange and mighty object exploded and shook the clouds.

On January 18, 1914, young Babalola was taken by his brother M. 0. Rotimi, a Sunday school teacher in the C.M.S. Church at Ilofa, to Osogbo. Babalola started school at Ilofa and got as far as standard five at All Saints’ School, Osogbo. However, he quit school when he decided to learn a trade and became a motor mechanic apprentice. Again, he did not continue long in this vocation before joining the Public Works Department (PWD). He was among the road workers who constructed the road from Igbara-Oke to Ilesa, working as a steam roller driver.

Babalola’s Call to the Prophetic Ministry

Just like the Old Testament prophets, Babalola was called by God into the prophetic office to stand before men. His was a specific and personal call.

Babalola’s strange experience started on the night of September 25th, 1928 when he suddenly became restless and could not sleep. This went on for a week and he had no inkling of the causes of such a strange experience. The climax came one day when he was, as usual, working on the Ilesa-Igbara-Oke road. Suddenly the steam roller’s engin stopped to his utter amazement. There was no visible mechanical problem, and Joseph became confused and perplexed. He was in this state of confusion when a great voice “like the sound of many waters” called him three times. The voice was loud and clear and it told him that he would die if he refused to heed the divine call to go into the world and preach. Babalola did not want to listen to this voice and he responded like many of the Biblical prophets, who, when they were called out by Yahweh as prophets, did not normally yield to the first call. Men like Moses and Jeremiah submitted to God only when it became inevitable. So, Babalola gave in only after he had received the assurance of divine guidance.

To go on the mission, he had to resign his appointment with the Public Works Department. Mr. Fergusson, the head of his unit, tried to dissuade him from resigning but the young man was bent on going on the Lord’s mission.

The same voice came to Joseph a second time asking him to fast for seven days. He obeyed and at the end of the period he saw a great figure of a man who, according to Pastor Alokan, resembled Jesus. The man in a dazzling robe spoke at length about the mission he was to embark upon. The man also told him of the persecutions he would face and at the same time assured him of God’s protection and victory. A hand prayer bell was given to Babalola as a symbol. He was told that the sound of the bell would always drive away evil spirits. He was also given a bottle of “life-giving water” to heal all manners of sickness. Consequently, wherever and whenever he prayed into water for therapeutic purposes, effective healing was procured for those who drank the water. Thus, Babalola became a prophet and a man with extraordinary powers. Enabled by the power of the Holy Spirit he could spend several weeks in prayer. Elder Abraham Owoyemi of Odo-Owa, said that the prophet regularly saw angels who delivered divine messages to him. An angel appeared in one of his prayers and forbade him to wear caps.

The Itinerary of Prophet Babalola

During one of his prayer sessions an angel appeared to him and gave him a big yam which he ordered him to eat. The angel told him that the yam was the tuber with which God fed the whole world. He further revealed that God had granted unto him the power to deliver those who were possessed of evil spirits in the world. He was directed to go first to Odo-Owa and start preaching. He was to arrive in the town on a market day, cover his body with palm fronds and disfigure himself with charcoal paints.

In October 1928, he entered the town in the manner described and was taken for a mad man. Babalola immediately started preaching and prophesying. He told the inhabitants of Odo-Owa about an impending danger if they did not repent. He was arrested and taken to the district officer at Ilorin for allegedly disturbing the peace. The district officer later released him when the allegations could not be proven. However, it was said that a few days later, there was an outbreak of smallpox in the town. The man whose prophecies and messages were once rejected was quickly sought for. He went around praying for the victims and they were all healed.

Pa David Rotimi, Babalola’s father, had been instrumental in the establishment of a C.M.S. Church in Odo-Owa. Babalola organized regular prayer meetings in this church which many people attended because of the miracles God performed through him. Among the regulars was Isaiah 01uyemi who later saw the wrath of Bishop Smith of Ilorin diocese. Information had reached the bishop that almost all members of the C.M.S. Church in Ilofa were seeing visions, speaking in tongues and praying vigorously. Babalola and the visionaries were allegedly ordered by Bishop Smith to leave the church. But Babalola did not leave the town until June 1930.

On an invitation from Daniel Ajibola, Babalola went to Lagos. Elder Daniel Ajibola at that time was working in Ibadan where he was a member of the Faith Tabernacle Congregation. He introduced Prophet Babalola to Pastor D. 0. Odubanjo, one of the leaders of the Faith Tabemacle in Lagos. Senior Pastor Esinsinade who was then the president of the Faith Tabernacle was invited to see Babalola. After listening to the details of his call and his ministry, the Faith Tabernacle leaders warmly received the young prophet into their midst.

Babalola had not yet been baptized by immersion and Senior Pastor Esinsinade emphasized that he needed to go through that rite. Pastor Esinsinade then baptized him in the lagoon at the back of the Faith Tabernacle Church building at 51, Moloney Bridge Street, Lagos. Babalola returned to Odo-Owa a few days after that and Elder (later Pastor) J. A. Medayese, paid him a visit.

The news of the conversion of the new prophet reached Pastor K. P. Titus at Araromi in Yagba, present Kwara State. Pastor Titus was a teacher and preacher at the Sudan Interior Mission which was then thriving at Yagba. He invited Prophet Babalola for a revival service. Joseph Ayodele Babalola while in Yagba, performed mighty works of healing. Many Muslims and Christians from other denominations and some traditional religionists were converted to the new faith during the revival.

The fact that Babalola did not use the opportunity to establish a separate Christian organization despite his marvelous evangelical success, must be puzzling to historians, but his intention was not to start a new church. He declared to his followers that he had registered his membership with the Faith Tabernacle, the society which had him baptized in Lagos. He thus persuaded them to become members of the Faith Tabernacle. To facilitate this, he went to Lagos to confer with the leaders, especially as he was not yet well acquainted with the doctrines, tenets, and administration of the church.

Oke-Oye Mighty Revival

There was a controversy among the leaders of the Faith Tabernacle in Nigeria over some doctrines. In the midst of it were, in particular, the Ilesa and Oyan branches of the tabernacle. The Oyan branch was under the supervision of Pastor J. A. Babatope, a notable Anglican teacher, before his conversion and later, one of the outstanding leaders of the Faith Tabernacle in Nigeria. Issues like the use of western and traditional drugs versus divine healing, polygamy and whether polygamous husbands should be allowed to partake of the Lord’s Supper, were among those doctrines that needed to be agreed on. These issues had caused dissension at the IIesa Tabernacle and in order to avoid a split, a delegation of peacemakers made up of all leading Faith Tabernacle pastors, was sent to Ilesa. It was headed by Pastor J. B. Esinsinade of Ijebu-Ode, president of the General Headquarters of the movement and D. O. Odubanjo of the Lagos Missionary Headquarters. The Ilesa meeting was scheduled for the 9th and lOth of July, 1930. The Apostolic Council of Jerusalem in A.D. 48, and other important church councils, are precedents in seeking ecclesiastical direction on matters affecting the life and peace of the church.

Before the delegation left Lagos for Ilesa, Babalola had been invited to meet the leaders at Pastor I. B. Akinyele’s residence at Ibadan. From there I. B. Akinyele and Babalola joined the delegation to Ilesa. At Ilesa, he was introduced to the whole conference and was lodged in a separate room because of his prophetic mission. The representatives began their meeting and on the agenda were twenty-four items. The first was the validity of baptism administered to a man with many wives. The second was the issue of divine healing because some of the members believed in the use of drugs like quinine to cure malaria fever. They were only able to discuss the first item when there was a sudden interruption which Pastor Adegboyega described thus: “The concilatory talks at Ilesa were going on, when suddenly a mighty sweeping revival broke out at Faith Tabernacle Congregation Church at Oke-Oye, Ilesa”. The revival began with the raising by Babalola of a dead child. The mother of the dead child who was restored to life went about spreading the news around the town of Ilesa proclaiming that a miracle working prophet had come to the town of Oke-Oye. This attracted a large number of people to Oke-Oye to see the prophet. According to Pastor Medayese, many of those afflicted with various diseases who came to Oke-Oye were healed. Many mighty works were performed through the use of the prayer bell and the drinking of consecrated water from a stream called Omi Ayo (“Stream of Joy”).

The result was that thousands of people including traditional religionists, Muslims and Christians from various other denominations were converted to the Faith Tabernacle. As there was no space in the church hall, revival meetings were shifted to an open field where men and women from all walks of life, from every part of the country and from neighbouring countries assembled daily for healing, deliverances and blessings. Odubanjo testified that within three weeks Babalola had cured about one hundred lepers, sixty blind people and fifty lame persons.

He further claimed that both the Anglican and Wesleyan Churches in Ilesa were left desolate because their members transferred their allegiance to the revivalist and that all the patients in Wesley Hospital, Ilesa, abandoned their beds to seek healing from Babalola.

The assistant district officer in Ilesa in 1930 wrote that he visited the scene of the revival incognito and found a crowd of hundreds of people including a large contingent of the lame and blind and concluded that the whole affair was orderly. Members of the church made fantastic claims such as: “Hopeless barren women were made fruitful; women who had been carrying their pregnancies for long years were wonderfully delivered. The dumb spoke and lunatics were cured. In fact, it was another day of Pentecost. Witches confessed and some demon possessed people were exorcized.

But the general superintendent of the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society of Nigeria at the time has described the reports as “grotesquely inaccurate accounts of the operations of Babalola.” This of course could be the biased view of a man whose church was said to be the greatest victim of the Ilesa revival.

A revelation was later given to Ayo Babalola to burn down a big tree in front of the Owa’s Palace. The big tree was traditionally believed to be the rendez-vous of witches and wizards. The juju tree was therefore greatly feared and sacrifices were usually made to the spirits believed to reside in it. There was apprehension that this bold act would result in the instantaneous death of Babalola since it was expected to arouse the anger of the gods. But to the great amazement of the people, the prophet did not die but rather continued to wax stronger in the Lord’s work. That single event was said to have made even the Owa of Ilesa and important people in the town to fear and respect the prophet.

The tidal wave of Babalola’s revival spread from Ilesa to Ibadan, Ijebu, Lagos, Efon-Alaaye, Aramoko Ekiti and Abeokuta. No greater revival preceded that of Babalola. It was popularly held in Christ Apostolic Church (C.A.C.) circles that at one revival meeting, attendance rose to about forty thousand. Among the men of faith who came as disciples to Babalola were Daniel Orekoya, Peter Olatunji who came from Okeho, and Omotunde, popularly known as Aladura Omotunde, from Aramoko Ekiti. These men drew great inspiration from Babalola. Orekoya went on to reside in Ibadan where a great revival also broke out at Oke-Bola through him. It was during his Oke-Bola revival that Orekoya reportedly raised a dead pregnant woman.

Babalola’s Other Missionary Journeys

After the great revival of Oke-Oye, the prophet was directed by the Holy Spirit to go out on further missionary journeys, but even before this, people from other parts of the country had been spreading the glad tidings of Oke-Oye, Ilesa’s great revival, to other parts of the country. Accompanied by some followers, Joseph Babalola went to Offa, in present Kwara State. Characteristically, people turned out to hear his preaching and see miracles. The Muslims in Offa became jealous and for that reason incited the members of the community against him. To avoid bloodshed he was compelled to leave.

He next stopped in Usi in Ekitiland for his evangelical mission and he performed many works of healing. From Usi he and his men moved to Efon-Alaaye, also in Ekitiland, where they received a warm reception from the Oba Alaaye of Efon. An entire building was provided for their comfort. Babalola requested an open space for prayer from the Oba who willingly and cheerfully gave him the privilege to choose a site. Consequently, the prophet and his men chose a large area at the outskirts of town. Traditionally the place was a forbidden forest because of the evil spirits that were believed to inhabit it. The Oba tried to dissuade Babalola and his men from entering the forbidden forest, but Babalola insisted on establishing his prayer ground there. The missionaries entered the bush, cleared it and consecrated it as a prayer ground. When no harm came upon them, the inhabitants of Efon were inspired to accept the new faith in large numbers.

Babalola’s evangelistic success in Efon-Alaaye was a remarkable one. Archdeacon H. Dallimore from Ado-Ekiti and some white pastors from Ogbomoso Baptist Seminary were believed to have come to see for themselves the “wonder-working prophet” at Efon. Both Dallimure and the Baptist pastors reportedly asked some men from St. Andrew’s College, Oyo and Baptist Seminary, Ogbomoso to assist in the work.

The success of the revival was accelerated by the conversion of both the Oba of Efon and the Oba of Aramoko. They were both baptized with the names, Solomon Aladejare Agunsoye and Hezekiah Adeoye respectively. After this event, news of the revival at Efon spread to other parts of Ekitiland.

The missionaries also visited other towns in the present Ondo State. Among them were Owo, Ikare and Oka. Babalola retreated to his home town in Odo-Owa to fortify himself spiritually. While he was at Odo-Owa, a warrant for his arrest was issued from Ilorin. He was arrested for preaching against witches, a practice which had caused some trouble in Otuo in present Bendel State. He was sentenced to jail for six months in Benin City in March 1932. After serving the jail term, he went back to Efon Alaaye.

One Mr. Cyprian E. Ufon came from Creek Town in Calabar to entreat Babalola to “come over to Macedonia and help.” Ufon had heard about Babalola and his works and wanted him to preach in Creek Town. After seeking God’s direction, the prophet followed Ufon to Creek Town. His campaign there was very successful. From Creek Town, Babalola visited Duke town and a plantation where a national church existed at the time. Certain members of this church received the gift of the Holy Spirit as Babalola was preaching to them and were baptized. When the prophet returned from the Calabar area, he settled down for a while. In 1935 he married Dorcas.

The following year Babalola, accompanied by Evangelist Timothy Bababusuyi, went to the Gold Coast. On arrival at Accra, he was recognized by some people who had seen him at the Great Revival in Ilesa. After a successful campaign in the Gold Coast he returned to Nigeria.

The Birth of the C.A.C. in Nigeria

The spectacular evangelism by Prophet Joseph Ayo Babalola brought with it a wave of persecution to all who rushed into the new faith. The mission churches allegedly became jealous and hostile especially as their members constituted the main converts of the Faith Tabernacle. It was widely rumoured that the revival movement was a lawless and unruly organization. The Nigerian government was put on the alert about the activities of the movement. At this time, the leading members of the movement were advised to invite the American Faith Tabernacle leaders to come to their rescue. The leaders from America, however, refused to come as such a venture was said to be against their principles. As a matter of fact, the association between the Philadelphia group and the Faith Tabernacle of Nigeria was terminated following the marital problems of the leader of the American group, Pastor Clark. The Nigerian group then went into fellowship with the Faith and Truth Temple of Toronto which sent a party of seven missionaries to West Africa. Again, the fellowship was stopped when Mr. C. R. Myers, the only surviving missionary, sent his wife to the hospital where she died in childbirth.

Despite these disappointing relationships with foreign groups, the Nigerian Faith Tabernacle still considered it prestigious to seek affiliation with a foreign body. The rationale for this can be found in D. 0. Odubanjo’s letter to Pastor D. P. Williams of the Apostolic Church of Great Britain of March 1931. In the letter Odubanjo claimed: “The officers of the government here fear the European missionaries, and dare not trouble their native converts, but often, we brethren here have been ill-treated by government officers”.

This was followed by a formal request for missionaries to be sent to strengthen the position of the Nigerian Faith Tabernacle. Missionaries did come and, on their advice, the Nigerian Faith Tabernacle was ceded to the British Apostolic Church. Consequently, the name changed from Faith Tabernacle to the Apostolic Church.

Doctrinal differences between the two groups soon began to appear in forms similar to the ones that caused the termination of the association with the American groups. The subject of divine healing, was one of the most important issues. Some of the invited white missionaries from Britain were found using quinine and other tablets and this caused a serious controversy among the leading members. It was unfortunate that the controversy could not be resolved and the movement subsequently split. One faction of the church made Oke-Oye its base and retained the name the Apostolic Church. The other larger faction and in which Prophet Joseph Babalola was a leader eventually became the Christ Apostolic Church. This church had to go through many names before May 1943 when its title was finally registered with number 147 under the Nigerian Company Law of 1924. Today, the church controls over five thousand assemblies, and reputedly is one of the most popular Christian organisations in Nigeria and the only indigenous organization with strong faith in divine healing.

Professor John Peel recorded that the membership of the C.A.C. in 1968 was well over one hundred thousand. That figure must have doubled by now. The church opened up several primary and grammar schools, a teachers’ training college, a seminary, maternity homes and a training school for prophets. The years between 1970 and 1980 saw further expansion of the church to England, Ivory Coast, Sierra Leone and Liberia. At present the church has its Missionary and General Headquarters in Lagos and Ibadan respectively.

Babalola was a spiritually gifted individual who was genuinely dissatisfied with the increasing materialistic and sinful existence into which he believed, the Yoruba in particular and Nigeria in general were being plunged as western civilization influence on society grew.

The C.A.C. believes that the spiritual power bestowed on Babalola placed him on an equal level with Biblical apostles like Peter, Paul and others who were sent out with the authority and in the name of Jesus.

Joseph Ayo Babalola slept in the Lord in 1959.

David O. Olayiwola

His Background

Joseph Ayodele Babalola was born on April 25, 1904 to David Rotimi and Madam Marta Talabi who belonged to the Anglican Church. The family lived at Odo-Owa in Ilofa, a small town about ninety kilometres from Ilorin in Kwara State, Nigeria. His father was the Baba Ijo (“church father”) of the C.M.S. Church at Odo-Owa. Pastor Medayese wrote in his book Itan Igbe dide Woli Ayo Babalola that mysterious circumstances surrounded the birth of Babalola. On that day, it was believed that a strange and mighty object exploded and shook the clouds.

On January 18, 1914, young Babalola was taken by his brother M. 0. Rotimi, a Sunday school teacher in the C.M.S. Church at Ilofa, to Osogbo. Babalola started school at Ilofa and got as far as standard five at All Saints’ School, Osogbo. However, he quit school when he decided to learn a trade and became a motor mechanic apprentice. Again, he did not continue long in this vocation before joining the Public Works Department (PWD). He was among the road workers who constructed the road from Igbara-Oke to Ilesa, working as a steam roller driver.

Babalola’s Call to the Prophetic Ministry

Just like the Old Testament prophets, Babalola was called by God into the prophetic office to stand before men. His was a specific and personal call.

Babalola’s strange experience started on the night of September 25th, 1928 when he suddenly became restless and could not sleep. This went on for a week and he had no inkling of the causes of such a strange experience. The climax came one day when he was, as usual, working on the Ilesa-Igbara-Oke road. Suddenly the steam roller’s engin stopped to his utter amazement. There was no visible mechanical problem, and Joseph became confused and perplexed. He was in this state of confusion when a great voice “like the sound of many waters” called him three times. The voice was loud and clear and it told him that he would die if he refused to heed the divine call to go into the world and preach. Babalola did not want to listen to this voice and he responded like many of the Biblical prophets, who, when they were called out by Yahweh as prophets, did not normally yield to the first call. Men like Moses and Jeremiah submitted to God only when it became inevitable. So, Babalola gave in only after he had received the assurance of divine guidance.

To go on the mission, he had to resign his appointment with the Public Works Department. Mr. Fergusson, the head of his unit, tried to dissuade him from resigning but the young man was bent on going on the Lord’s mission.

The same voice came to Joseph a second time asking him to fast for seven days. He obeyed and at the end of the period he saw a great figure of a man who, according to Pastor Alokan, resembled Jesus. The man in a dazzling robe spoke at length about the mission he was to embark upon. The man also told him of the persecutions he would face and at the same time assured him of God’s protection and victory. A hand prayer bell was given to Babalola as a symbol. He was told that the sound of the bell would always drive away evil spirits. He was also given a bottle of “life-giving water” to heal all manners of sickness. Consequently, wherever and whenever he prayed into water for therapeutic purposes, effective healing was procured for those who drank the water. Thus, Babalola became a prophet and a man with extraordinary powers. Enabled by the power of the Holy Spirit he could spend several weeks in prayer. Elder Abraham Owoyemi of Odo-Owa, said that the prophet regularly saw angels who delivered divine messages to him. An angel appeared in one of his prayers and forbade him to wear caps.

The Itinerary of Prophet Babalola

During one of his prayer sessions an angel appeared to him and gave him a big yam which he ordered him to eat. The angel told him that the yam was the tuber with which God fed the whole world. He further revealed that God had granted unto him the power to deliver those who were possessed of evil spirits in the world. He was directed to go first to Odo-Owa and start preaching. He was to arrive in the town on a market day, cover his body with palm fronds and disfigure himself with charcoal paints.

In October 1928, he entered the town in the manner described and was taken for a mad man. Babalola immediately started preaching and prophesying. He told the inhabitants of Odo-Owa about an impending danger if they did not repent. He was arrested and taken to the district officer at Ilorin for allegedly disturbing the peace. The district officer later released him when the allegations could not be proven. However, it was said that a few days later, there was an outbreak of smallpox in the town. The man whose prophecies and messages were once rejected was quickly sought for. He went around praying for the victims and they were all healed.

Pa David Rotimi, Babalola’s father, had been instrumental in the establishment of a C.M.S. Church in Odo-Owa. Babalola organized regular prayer meetings in this church which many people attended because of the miracles God performed through him. Among the regulars was Isaiah 01uyemi who later saw the wrath of Bishop Smith of Ilorin diocese. Information had reached the bishop that almost all members of the C.M.S. Church in Ilofa were seeing visions, speaking in tongues and praying vigorously. Babalola and the visionaries were allegedly ordered by Bishop Smith to leave the church. But Babalola did not leave the town until June 1930.

On an invitation from Daniel Ajibola, Babalola went to Lagos. Elder Daniel Ajibola at that time was working in Ibadan where he was a member of the Faith Tabernacle Congregation. He introduced Prophet Babalola to Pastor D. 0. Odubanjo, one of the leaders of the Faith Tabemacle in Lagos. Senior Pastor Esinsinade who was then the president of the Faith Tabernacle was invited to see Babalola. After listening to the details of his call and his ministry, the Faith Tabernacle leaders warmly received the young prophet into their midst.

Babalola had not yet been baptized by immersion and Senior Pastor Esinsinade emphasized that he needed to go through that rite. Pastor Esinsinade then baptized him in the lagoon at the back of the Faith Tabernacle Church building at 51, Moloney Bridge Street, Lagos. Babalola returned to Odo-Owa a few days after that and Elder (later Pastor) J. A. Medayese, paid him a visit.

The news of the conversion of the new prophet reached Pastor K. P. Titus at Araromi in Yagba, present Kwara State. Pastor Titus was a teacher and preacher at the Sudan Interior Mission which was then thriving at Yagba. He invited Prophet Babalola for a revival service. Joseph Ayodele Babalola while in Yagba, performed mighty works of healing. Many Muslims and Christians from other denominations and some traditional religionists were converted to the new faith during the revival.

The fact that Babalola did not use the opportunity to establish a separate Christian organization despite his marvelous evangelical success, must be puzzling to historians, but his intention was not to start a new church. He declared to his followers that he had registered his membership with the Faith Tabernacle, the society which had him baptized in Lagos. He thus persuaded them to become members of the Faith Tabernacle. To facilitate this, he went to Lagos to confer with the leaders, especially as he was not yet well acquainted with the doctrines, tenets, and administration of the church.

Oke-Oye Mighty Revival

There was a controversy among the leaders of the Faith Tabernacle in Nigeria over some doctrines. In the midst of it were, in particular, the Ilesa and Oyan branches of the tabernacle. The Oyan branch was under the supervision of Pastor J. A. Babatope, a notable Anglican teacher, before his conversion and later, one of the outstanding leaders of the Faith Tabernacle in Nigeria. Issues like the use of western and traditional drugs versus divine healing, polygamy and whether polygamous husbands should be allowed to partake of the Lord’s Supper, were among those doctrines that needed to be agreed on. These issues had caused dissension at the IIesa Tabernacle and in order to avoid a split, a delegation of peacemakers made up of all leading Faith Tabernacle pastors, was sent to Ilesa. It was headed by Pastor J. B. Esinsinade of Ijebu-Ode, president of the General Headquarters of the movement and D. O. Odubanjo of the Lagos Missionary Headquarters. The Ilesa meeting was scheduled for the 9th and lOth of July, 1930. The Apostolic Council of Jerusalem in A.D. 48, and other important church councils, are precedents in seeking ecclesiastical direction on matters affecting the life and peace of the church.

Before the delegation left Lagos for Ilesa, Babalola had been invited to meet the leaders at Pastor I. B. Akinyele’s residence at Ibadan. From there I. B. Akinyele and Babalola joined the delegation to Ilesa. At Ilesa, he was introduced to the whole conference and was lodged in a separate room because of his prophetic mission. The representatives began their meeting and on the agenda were twenty-four items. The first was the validity of baptism administered to a man with many wives. The second was the issue of divine healing because some of the members believed in the use of drugs like quinine to cure malaria fever. They were only able to discuss the first item when there was a sudden interruption which Pastor Adegboyega described thus: “The concilatory talks at Ilesa were going on, when suddenly a mighty sweeping revival broke out at Faith Tabernacle Congregation Church at Oke-Oye, Ilesa”. The revival began with the raising by Babalola of a dead child. The mother of the dead child who was restored to life went about spreading the news around the town of Ilesa proclaiming that a miracle working prophet had come to the town of Oke-Oye. This attracted a large number of people to Oke-Oye to see the prophet. According to Pastor Medayese, many of those afflicted with various diseases who came to Oke-Oye were healed. Many mighty works were performed through the use of the prayer bell and the drinking of consecrated water from a stream called Omi Ayo (“Stream of Joy”).

The result was that thousands of people including traditional religionists, Muslims and Christians from various other denominations were converted to the Faith Tabernacle. As there was no space in the church hall, revival meetings were shifted to an open field where men and women from all walks of life, from every part of the country and from neighbouring countries assembled daily for healing, deliverances and blessings. Odubanjo testified that within three weeks Babalola had cured about one hundred lepers, sixty blind people and fifty lame persons.

He further claimed that both the Anglican and Wesleyan Churches in Ilesa were left desolate because their members transferred their allegiance to the revivalist and that all the patients in Wesley Hospital, Ilesa, abandoned their beds to seek healing from Babalola.

The assistant district officer in Ilesa in 1930 wrote that he visited the scene of the revival incognito and found a crowd of hundreds of people including a large contingent of the lame and blind and concluded that the whole affair was orderly. Members of the church made fantastic claims such as: “Hopeless barren women were made fruitful; women who had been carrying their pregnancies for long years were wonderfully delivered. The dumb spoke and lunatics were cured. In fact, it was another day of Pentecost. Witches confessed and some demon possessed people were exorcized.

But the general superintendent of the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society of Nigeria at the time has described the reports as “grotesquely inaccurate accounts of the operations of Babalola.” This of course could be the biased view of a man whose church was said to be the greatest victim of the Ilesa revival.

A revelation was later given to Ayo Babalola to burn down a big tree in front of the Owa’s Palace. The big tree was traditionally believed to be the rendez-vous of witches and wizards. The juju tree was therefore greatly feared and sacrifices were usually made to the spirits believed to reside in it. There was apprehension that this bold act would result in the instantaneous death of Babalola since it was expected to arouse the anger of the gods. But to the great amazement of the people, the prophet did not die but rather continued to wax stronger in the Lord’s work. That single event was said to have made even the Owa of Ilesa and important people in the town to fear and respect the prophet.

The tidal wave of Babalola’s revival spread from Ilesa to Ibadan, Ijebu, Lagos, Efon-Alaaye, Aramoko Ekiti and Abeokuta. No greater revival preceded that of Babalola. It was popularly held in Christ Apostolic Church (C.A.C.) circles that at one revival meeting, attendance rose to about forty thousand. Among the men of faith who came as disciples to Babalola were Daniel Orekoya, Peter Olatunji who came from Okeho, and Omotunde, popularly known as Aladura Omotunde, from Aramoko Ekiti. These men drew great inspiration from Babalola. Orekoya went on to reside in Ibadan where a great revival also broke out at Oke-Bola through him. It was during his Oke-Bola revival that Orekoya reportedly raised a dead pregnant woman.

Babalola’s Other Missionary Journeys

After the great revival of Oke-Oye, the prophet was directed by the Holy Spirit to go out on further missionary journeys, but even before this, people from other parts of the country had been spreading the glad tidings of Oke-Oye, Ilesa’s great revival, to other parts of the country. Accompanied by some followers, Joseph Babalola went to Offa, in present Kwara State. Characteristically, people turned out to hear his preaching and see miracles. The Muslims in Offa became jealous and for that reason incited the members of the community against him. To avoid bloodshed he was compelled to leave.

He next stopped in Usi in Ekitiland for his evangelical mission and he performed many works of healing. From Usi he and his men moved to Efon-Alaaye, also in Ekitiland, where they received a warm reception from the Oba Alaaye of Efon. An entire building was provided for their comfort. Babalola requested an open space for prayer from the Oba who willingly and cheerfully gave him the privilege to choose a site. Consequently, the prophet and his men chose a large area at the outskirts of town. Traditionally the place was a forbidden forest because of the evil spirits that were believed to inhabit it. The Oba tried to dissuade Babalola and his men from entering the forbidden forest, but Babalola insisted on establishing his prayer ground there. The missionaries entered the bush, cleared it and consecrated it as a prayer ground. When no harm came upon them, the inhabitants of Efon were inspired to accept the new faith in large numbers.

Babalola’s evangelistic success in Efon-Alaaye was a remarkable one. Archdeacon H. Dallimore from Ado-Ekiti and some white pastors from Ogbomoso Baptist Seminary were believed to have come to see for themselves the “wonder-working prophet” at Efon. Both Dallimure and the Baptist pastors reportedly asked some men from St. Andrew’s College, Oyo and Baptist Seminary, Ogbomoso to assist in the work.

The success of the revival was accelerated by the conversion of both the Oba of Efon and the Oba of Aramoko. They were both baptized with the names, Solomon Aladejare Agunsoye and Hezekiah Adeoye respectively. After this event, news of the revival at Efon spread to other parts of Ekitiland.

The missionaries also visited other towns in the present Ondo State. Among them were Owo, Ikare and Oka. Babalola retreated to his home town in Odo-Owa to fortify himself spiritually. While he was at Odo-Owa, a warrant for his arrest was issued from Ilorin. He was arrested for preaching against witches, a practice which had caused some trouble in Otuo in present Bendel State. He was sentenced to jail for six months in Benin City in March 1932. After serving the jail term, he went back to Efon Alaaye.

One Mr. Cyprian E. Ufon came from Creek Town in Calabar to entreat Babalola to “come over to Macedonia and help.” Ufon had heard about Babalola and his works and wanted him to preach in Creek Town. After seeking God’s direction, the prophet followed Ufon to Creek Town. His campaign there was very successful. From Creek Town, Babalola visited Duke town and a plantation where a national church existed at the time. Certain members of this church received the gift of the Holy Spirit as Babalola was preaching to them and were baptized. When the prophet returned from the Calabar area, he settled down for a while. In 1935 he married Dorcas.

The following year Babalola, accompanied by Evangelist Timothy Bababusuyi, went to the Gold Coast. On arrival at Accra, he was recognized by some people who had seen him at the Great Revival in Ilesa. After a successful campaign in the Gold Coast he returned to Nigeria.

The Birth of the C.A.C. in Nigeria

The spectacular evangelism by Prophet Joseph Ayo Babalola brought with it a wave of persecution to all who rushed into the new faith. The mission churches allegedly became jealous and hostile especially as their members constituted the main converts of the Faith Tabernacle. It was widely rumoured that the revival movement was a lawless and unruly organization. The Nigerian government was put on the alert about the activities of the movement. At this time, the leading members of the movement were advised to invite the American Faith Tabernacle leaders to come to their rescue. The leaders from America, however, refused to come as such a venture was said to be against their principles. As a matter of fact, the association between the Philadelphia group and the Faith Tabernacle of Nigeria was terminated following the marital problems of the leader of the American group, Pastor Clark. The Nigerian group then went into fellowship with the Faith and Truth Temple of Toronto which sent a party of seven missionaries to West Africa. Again, the fellowship was stopped when Mr. C. R. Myers, the only surviving missionary, sent his wife to the hospital where she died in childbirth.

Despite these disappointing relationships with foreign groups, the Nigerian Faith Tabernacle still considered it prestigious to seek affiliation with a foreign body. The rationale for this can be found in D. 0. Odubanjo’s letter to Pastor D. P. Williams of the Apostolic Church of Great Britain of March 1931. In the letter Odubanjo claimed: “The officers of the government here fear the European missionaries, and dare not trouble their native converts, but often, we brethren here have been ill-treated by government officers”.

This was followed by a formal request for missionaries to be sent to strengthen the position of the Nigerian Faith Tabernacle. Missionaries did come and, on their advice, the Nigerian Faith Tabernacle was ceded to the British Apostolic Church. Consequently, the name changed from Faith Tabernacle to the Apostolic Church.

Doctrinal differences between the two groups soon began to appear in forms similar to the ones that caused the termination of the association with the American groups. The subject of divine healing, was one of the most important issues. Some of the invited white missionaries from Britain were found using quinine and other tablets and this caused a serious controversy among the leading members. It was unfortunate that the controversy could not be resolved and the movement subsequently split. One faction of the church made Oke-Oye its base and retained the name the Apostolic Church. The other larger faction and in which Prophet Joseph Babalola was a leader eventually became the Christ Apostolic Church. This church had to go through many names before May 1943 when its title was finally registered with number 147 under the Nigerian Company Law of 1924. Today, the church controls over five thousand assemblies, and reputedly is one of the most popular Christian organisations in Nigeria and the only indigenous organization with strong faith in divine healing.

Professor John Peel recorded that the membership of the C.A.C. in 1968 was well over one hundred thousand. That figure must have doubled by now. The church opened up several primary and grammar schools, a teachers’ training college, a seminary, maternity homes and a training school for prophets. The years between 1970 and 1980 saw further expansion of the church to England, Ivory Coast, Sierra Leone and Liberia. At present the church has its Missionary and General Headquarters in Lagos and Ibadan respectively.

Babalola was a spiritually gifted individual who was genuinely dissatisfied with the increasing materialistic and sinful existence into which he believed, the Yoruba in particular and Nigeria in general were being plunged as western civilization influence on society grew.

The C.A.C. believes that the spiritual power bestowed on Babalola placed him on an equal level with Biblical apostles like Peter, Paul and others who were sent out with the authority and in the name of Jesus.

Joseph Ayo Babalola slept in the Lord in 1959.

David O. Olayiwola

Suffering Under an All-Powerful Love

As I sat atop my lofted dorm-room bed and turned the page from Romans 8 to Romans 9 in my small, tattered Bible, I went from a chapter familiar enough to be easily skimmed to a chapter that I had no recollection of ever reading before. Both chapters emphasized the sovereignty of God — his sovereign love and his sovereign power. At 19 years old, I had not thought much about God’s sovereignty. I believed what I’d been taught as a child — that God was in control, that he knew every hair on my head, that he had the whole world in his hands. But I also believed that salvation was a choice I had made — that God chose me because he knew I’d someday choose him. When I entered college, however, the issue became inescapable. My college campus swirled with discussions about whether God elected people to salvation and whether he could know the future at all. Even my theology class was getting ready to host a debate between an Open Theist (someone who believes God doesn’t fully know the future until it happens) and a Calvinist (someone who believes God knows and ordains the future, including who will believe and be saved). It was only by chance that I had been reading Romans 8–9 the night before this debate. Or was it? God in Control That night, my beliefs began to change. I read of God’s relationship with his chosen people: Those whom he foreknew he also predestined to be conformed to the image of his Son, in order that he might be the firstborn among many brothers. And those whom he predestined he also called, and those whom he called he also justified, and those whom he justified he also glorified. (Romans 8:29–30) Could it possibly be true that this foreknowing, predestining God didn’t know the future? It could not. Or was it conceivable that the God who said, “It depends not on human will or exertion, but on God, who has mercy,” was merely looking ahead in the future to see who would and wouldn’t choose him (Romans 9:16)? It was not. And furthermore, God declared that he was working all things together for the good of those he’d called (Romans 8:28). Could God work all things together for good if all things were not genuinely under his control? My 19-year-old heart began to swell with joy and relief. This God was not back on his heels, trying to figure out what to do, nor was he waiting for me to figure him out. He was bringing his good plans to pass. He called me, he saved me, and he would keep me in every circumstance. Does God’s Goodness Miscarry? My understanding of God’s sovereign grace grew as my knowledge of God’s word grew. And I loved his sovereignty — in theory at least. I loved that my God was so powerful and big and in charge. When I saw others go through difficult circumstances, I sympathized with them, but I also had a settled sense that God had a plan born from his love. It wasn’t until I was up against my own difficult circumstance that the thought flashed in my mind: perhaps God was working something not good in my life. As a young wife and mom, I never considered the possibility of miscarrying. So when it happened, I was shocked that my own womb could become a place of death. All I knew of God flooded my mind, almost as a reproach. As I faced the loss of our little one, I wasn’t tempted to doubt his power but his love. I knew he could have kept our baby alive, so why didn’t he? Yet Romans 8 was there to keep me grounded, reminding me that not even death could separate us from his love. Paul’s words were an anchor: I am sure that neither death nor life, nor angels nor rulers, nor things present nor things to come, nor powers, nor height nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord. (Romans 8:38–39) As the years rolled on, God’s sovereignty over all things was the buoy that kept me afloat in every season. I was learning to trust God’s love as he carried us through job loss, babies received and one lost, moves, and new ministry. Yet it was the birth of our youngest son that brought the deepest challenge to my trust in God’s power and plans. With our son’s arrival, we faced uncertainty regarding his future, a future that, in the best case, would involve disability and health difficulties. During the chronic trials that ensued, including our son’s sleep disorder, seizures, and eating difficulties that involved years of almost daily vomit, a different sort of temptation occasionally crept in — the thought that God might love us, but he maybe couldn’t help us. Night after night after night, year after year after year, we would pray for relief. But relief didn’t come. Different Sort of Power I was looking for God’s power to come in the form of physical relief from our trials. I was tired and worn. I wanted to be free of the difficulties of nighttime G-tube feedings and regular vomit clean-up. If God answered those prayers, I reasoned, that would be a sign of his power. Yet which is more difficult: to change someone’s circumstances from hard to easy, or to change the person in the circumstances from floundering to flourishing despite it all? Would God have shown more of his sovereign power if he had put down all his enemies once and for all, preventing the cross and the resurrection? Or is God’s power more greatly displayed through his planning from before time to crush his Son, defeat sin, and then raise his Son from the dead, so that he could make his enemies his friends? Any tyrant with a large army can squelch his enemies, but only our gracious and powerful God turns enemies into sons through the folly of the cross and the empty tomb. As Paul testifies, God often manifests his power through our weaknesses. It was Paul’s thorn in the flesh that occasioned God’s sovereign power resting upon him: I will boast all the more gladly of my weaknesses, so that the power of Christ may rest upon me. For the sake of Christ, then, I am content with weaknesses, insults, hardships, persecutions, and calamities. For when I am weak, then I am strong. (2 Corinthians 12:9–10) “The sovereign power of God rests on his people, not to remove their thorns, but to teach them of a stronger power.” In a world where almost everyone seems obsessed with power — whether they have it, how they can get it — God’s word shows us the deeper power: the power of his Spirit. God’s power is ours when we entrust ourselves to him amid weakness. We need not demand power from the world. We need not seek position or platform. The sovereign power of God rests on his people, not to remove their thorns, but to teach them of a stronger power — the power of God that contents us with trials, so long as we have Christ’s Spirit. No Trite Slogan All those years ago as a college sophomore, Romans 8 and 9 showed me the sovereign love and sovereign power of God. In Romans 9, I met a God to whom back talk was not permitted: You will say to me then, “Why does he still find fault? For who can resist his will?” But who are you, O man, to answer back to God? Will what is molded say to its molder, “Why have you made me like this?” (Romans 9:19–20) In Romans 8, that same fearfully powerful God was also utterly committed to my good in all things, so much so, that his Spirit intercedes for me as he works on my behalf (Romans 8:26–28). Some believe that Romans 8:28 is a trite way to comfort the afflicted — that it shuts up the grief of the hurting, as though telling a suffering saint that God is working their hardship for good makes a mockery of the pain. As we are imperfect people, we should consider that possibility. But for me, no truth is as precious. “God is good. God is strong. Not one thing happens to us apart from his perfect plan.” Knowing that God is working all things for my good has been the dearest and deepest comfort, even, and especially, in the darkest of seasons. God is working all things for my good when our son is in the hospital (again), or when my husband is dealing with chronic pain (still), or when betrayal and slander touch my life or the lives of those I love. It’s a reality that keeps my heart whole even as it’s breaking, and my mind clear even in the fog of confusion. He is good. He is strong. Not one thing happens to us apart from his perfect plan. God’s sovereign love and power mean that we can trust him — now and forever. Article by Abigail Dodds Regular Contributor