Others like satan's rebellion and fall Features >>

Rapture, Revelation, And The End Times

Divine Revelation Of Gods Holiness And Judgement

Rapture, Revelation, And The End Times: Exploring The Left Behind Series

The Three Heavens

Angels On Assignment As Told By Roland H. Buck

Secrets From Beyond The Grave

The Dark Side Of The Supernatural

-160.webp)

Heaven Is For Real: A Little Boy's Astounding Story Of His Trip To Heaven And Back

Because The Time Is Near

-160.webp)

Proof Of Heaven: A Neurosurgeon's Journey Into The Afterlife

About the Book

"Satan's Rebellion and Fall" by Gordon Lindsay examines the biblical account of Lucifer's rebellion against God, his fall from grace, and the consequences of his actions. This book delves into the origins of evil and how it manifests in the world today, offering insights into the spiritual warfare that believers face. Lindsay's work provides a thought-provoking exploration of the nature of sin, redemption, and the ultimate victory of good over evil.

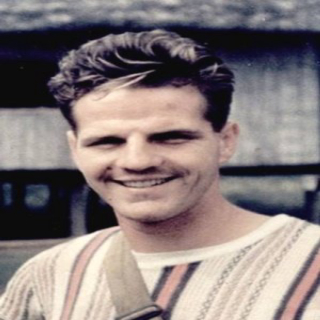

Jim Elliot

EARLY LIFE

Jim Elliot began his life in Portland, Oregon in the USA. His mother, Clara, was a chiropractor and his father, Fred, was a minister. They married and settled in Seattle, WA where they welcomed their first son, Robert in 1921.

Later they relocated the family to Portland where Herbert arrived in 1924, Jim in 1927, and Jane in 1932.

Jim knew Christ from an early age and was never afraid to speak about Him to his friends. At age six Jim told his mother, “Now, mama, the Lord Jesus can come whenever He wants. He could take our whole family because I’m saved now, and Jane is too young to know Him yet.”

THE YEARS THAT CEMENTED HIS DESIRE TO SERVE THE LORD IN MISSIONS

Jim entered Benson Polytechnic High School in 1941. He carried a small Bible with him and, an excellent speaker; he was often found speaking out for Christ. He and his friends were not afraid to step out and find adventure. One thing Jim didn’t have time for in those early years were girls. He was once quoted as telling a friend, “Domesticated males aren’t much use for adventure.”

In 1945 Jim traveled to Wheaton, IL to attend Wheaton College. His main goal while there was to devote himself to God. He recognized the importance of discipline in pursuing this goal. He would start each morning with prayer and Bible study. In his journal he wrote, “None of it gets to be ‘old stuff’ for it is Christ in print, the Living Word. We wouldn’t think of rising in the morning without a face-wash, but we often neglect the purgative cleansing of the Word of the Lord. It wakes us up to our responsibility.”

Jim’s desire to serve God by taking His gospel to unreached people of the world began to grow while at Wheaton. The summer of 1947 found him in Mexico and that time influenced his decision to minister in Central America after he finished college.

Jim met Elisabeth Howard during his third year at Wheaton. He did ask her for a date which she accepted and then later cancelled. They spent the next years as friends and after she finished at Wheaton they continued to correspond. As they came to know each other there was an attraction, but Jim felt he needed to unencumbered by worldly concerns in order to devote himself completely to God.

In addition to his hope to one day travel to a foreign country to share Christ with the unchurched of the world, he also felt the need to share with people in the United States. On Sundays while at Wheaton he would often ride the train into Chicago and talk to people in the train station about Christ. He often felt ineffective in his work as the times of knowingly leading people to Christ were few. He once wrote, “No fruit yet. Why is that I’m so unproductive? I cannot recall leading more than one or two into the kingdom. Surely this is not the manifestation of the power of the Resurrection. I feel as Rachel, ‘Give me children, or else I die.’”

After college with no clear answer as to working for the Lord in a foreign country, Jim returned home to Portland. He continued his disciplined Bible study as well as correspondence with Elisabeth Howard whom he called Betty.

They both felt a strong attraction to each other during this time, but also felt that the Lord may have been calling them to be unmarried as they served Him.

In June of 1950 he travelled to Oklahoma to attend the Summer Institute of Linguistics. There he learned how to study unwritten languages. He was able to work with a missionary to the Quichuas of the Ecuadorian jungle. Because of these lessons he began to pray for guidance about going to Ecuador and later felt compelled to answer the call there.

Elisabeth Elliot wrote in Shadow of the Almighty:

“The breadth of Jim’s vision is suggested in this entry from the journal:

August 9. “God just now gave me faith to ask for another young man to go, perhaps not this fall, but soon, to join the ranks in the lowlands of eastern Ecuador. There we must learn: 1) Spanish and Quichua, 2) each other, 3) the jungle and independence, and 4) God and God’s way of approach to the highland Quichua. From thence, by His great hand, we must move to the Ecuadorian highlands with several young Indians each, and begin work among the 800,000 highlanders. If God tarries, the natives must be taught to spread southward with the message of the reigning Christ, establishing New Testament groups as they go. Thence the Word must go south into Peru and Bolivia. The Quichuas must be reached for God! Enough for policy. Now for prayer and practice.

THE ECUADOR YEARS

In February 1952 Jim finally left America to travel to Ecuador with Pete Fleming. In May Elisabeth moved to Quito and though they didn’t feel the need to get engaged she and Jim did begin a courtship.

In August Jim left Elisabeth in Quito and travelled with Pete to Shell Mera. At the Mission Aviation Fellowship headquarters in Shell Mera, Jim and Pete learned more about the Acua Indians, a people group that was largely unreached and very savage.

Leaving Shell Mera, Pete and Jim moved on to Shandia where Jim was captivated by the Quichua. He felt very strongly that this was exactly where God intended for him to work to spread the Gospel.

While Jim was in Shandia, Elisabeth was working to learn more about the Colorado Indians near Santa Domingo. In January of 1953 he went to Quito and she met him there and they were finally engaged. They married in October of that year and their only child Valerie was born in 1955.

They settled in Shandia and continued their work with the Quichua Indians. It was Jim’s desire to be able to reach the Waodoni tribe that lived deep in the jungles and had little contact with the outside world. A Waodoni woman who had left the tribe was taken in by the missionaries and helped them to learn the language.

Jim, along with Pete, Ed McCully, Roger Youderian, and their pilot Nate Saint began to search by plane in hopes of finding a way to contact the Waodoni. The found a sandbar in the middle of the Curaray River that worked as a landing strip for the plane and it was there that they first made contact with the Waodoni. They were elated to be able to finally be able to attempt to share the love of Christ with this people group.

After their first meeting, one of the tribe, a man they called George lied to the tribe about the men’s intentions. This lie led the Waodoni warriors to plan an attack for when the missionaries returned. The men did return on January 8, 1956 and were surprised by ten members of the tribe who massacred the missionaries.

Jim’s short life that was filled with the desire to share God’s love can be summed up by a quote that is attributed to him. “He is no fool who gives that which he cannot keep, to gain what he cannot lose.”

EARLY LIFE

Jim Elliot began his life in Portland, Oregon in the USA. His mother, Clara, was a chiropractor and his father, Fred, was a minister. They married and settled in Seattle, WA where they welcomed their first son, Robert in 1921.

Later they relocated the family to Portland where Herbert arrived in 1924, Jim in 1927, and Jane in 1932.

Jim knew Christ from an early age and was never afraid to speak about Him to his friends. At age six Jim told his mother, “Now, mama, the Lord Jesus can come whenever He wants. He could take our whole family because I’m saved now, and Jane is too young to know Him yet.”

THE YEARS THAT CEMENTED HIS DESIRE TO SERVE THE LORD IN MISSIONS

Jim entered Benson Polytechnic High School in 1941. He carried a small Bible with him and, an excellent speaker; he was often found speaking out for Christ. He and his friends were not afraid to step out and find adventure. One thing Jim didn’t have time for in those early years were girls. He was once quoted as telling a friend, “Domesticated males aren’t much use for adventure.”

In 1945 Jim traveled to Wheaton, IL to attend Wheaton College. His main goal while there was to devote himself to God. He recognized the importance of discipline in pursuing this goal. He would start each morning with prayer and Bible study. In his journal he wrote, “None of it gets to be ‘old stuff’ for it is Christ in print, the Living Word. We wouldn’t think of rising in the morning without a face-wash, but we often neglect the purgative cleansing of the Word of the Lord. It wakes us up to our responsibility.”

Jim’s desire to serve God by taking His gospel to unreached people of the world began to grow while at Wheaton. The summer of 1947 found him in Mexico and that time influenced his decision to minister in Central America after he finished college.

Jim met Elisabeth Howard during his third year at Wheaton. He did ask her for a date which she accepted and then later cancelled. They spent the next years as friends and after she finished at Wheaton they continued to correspond. As they came to know each other there was an attraction, but Jim felt he needed to unencumbered by worldly concerns in order to devote himself completely to God.

In addition to his hope to one day travel to a foreign country to share Christ with the unchurched of the world, he also felt the need to share with people in the United States. On Sundays while at Wheaton he would often ride the train into Chicago and talk to people in the train station about Christ. He often felt ineffective in his work as the times of knowingly leading people to Christ were few. He once wrote, “No fruit yet. Why is that I’m so unproductive? I cannot recall leading more than one or two into the kingdom. Surely this is not the manifestation of the power of the Resurrection. I feel as Rachel, ‘Give me children, or else I die.’”

After college with no clear answer as to working for the Lord in a foreign country, Jim returned home to Portland. He continued his disciplined Bible study as well as correspondence with Elisabeth Howard whom he called Betty.

They both felt a strong attraction to each other during this time, but also felt that the Lord may have been calling them to be unmarried as they served Him.

In June of 1950 he travelled to Oklahoma to attend the Summer Institute of Linguistics. There he learned how to study unwritten languages. He was able to work with a missionary to the Quichuas of the Ecuadorian jungle. Because of these lessons he began to pray for guidance about going to Ecuador and later felt compelled to answer the call there.

Elisabeth Elliot wrote in Shadow of the Almighty:

“The breadth of Jim’s vision is suggested in this entry from the journal:

August 9. “God just now gave me faith to ask for another young man to go, perhaps not this fall, but soon, to join the ranks in the lowlands of eastern Ecuador. There we must learn: 1) Spanish and Quichua, 2) each other, 3) the jungle and independence, and 4) God and God’s way of approach to the highland Quichua. From thence, by His great hand, we must move to the Ecuadorian highlands with several young Indians each, and begin work among the 800,000 highlanders. If God tarries, the natives must be taught to spread southward with the message of the reigning Christ, establishing New Testament groups as they go. Thence the Word must go south into Peru and Bolivia. The Quichuas must be reached for God! Enough for policy. Now for prayer and practice.

THE ECUADOR YEARS

In February 1952 Jim finally left America to travel to Ecuador with Pete Fleming. In May Elisabeth moved to Quito and though they didn’t feel the need to get engaged she and Jim did begin a courtship.

In August Jim left Elisabeth in Quito and travelled with Pete to Shell Mera. At the Mission Aviation Fellowship headquarters in Shell Mera, Jim and Pete learned more about the Acua Indians, a people group that was largely unreached and very savage.

Leaving Shell Mera, Pete and Jim moved on to Shandia where Jim was captivated by the Quichua. He felt very strongly that this was exactly where God intended for him to work to spread the Gospel.

While Jim was in Shandia, Elisabeth was working to learn more about the Colorado Indians near Santa Domingo. In January of 1953 he went to Quito and she met him there and they were finally engaged. They married in October of that year and their only child Valerie was born in 1955.

They settled in Shandia and continued their work with the Quichua Indians. It was Jim’s desire to be able to reach the Waodoni tribe that lived deep in the jungles and had little contact with the outside world. A Waodoni woman who had left the tribe was taken in by the missionaries and helped them to learn the language.

Jim, along with Pete, Ed McCully, Roger Youderian, and their pilot Nate Saint began to search by plane in hopes of finding a way to contact the Waodoni. The found a sandbar in the middle of the Curaray River that worked as a landing strip for the plane and it was there that they first made contact with the Waodoni. They were elated to be able to finally be able to attempt to share the love of Christ with this people group.

After their first meeting, one of the tribe, a man they called George lied to the tribe about the men’s intentions. This lie led the Waodoni warriors to plan an attack for when the missionaries returned. The men did return on January 8, 1956 and were surprised by ten members of the tribe who massacred the missionaries.

Jim’s short life that was filled with the desire to share God’s love can be summed up by a quote that is attributed to him. “He is no fool who gives that which he cannot keep, to gain what he cannot lose.”

Though Dead, He Still Speaks - How Satan Remembers C.S. Lewis

The scene is in hell at the annual dinner of the Tempters’ Training College for young devils. The principal, Dr. Snufftub, has just proposed a toast to the health of the guests. Grimgod, a very experienced devil, who is the guest of honor, rises to reply: Headmaster, favorite Decadents, Ghouls, Fiends, and Imps, to my Intolerable Tempters, Ghastly Graduates, and Gentledevils: Gladly do I assume my place in our great tradition to charge our recent graduates towards highest malevolence, mischief, and devilry. I could begin my remarks by dribbling on about how honored I am to have been invited — but you, my lowly esteemed guests, are not humans to be flattered, and I, not a man to feign humility. I tell you plainly: I both deserve and expected to address you this evening. If but for that incompetent Dr. Slubgob — whose faults and failings (and finish) you are all keenly aware — I would have said my piece centuries ago. You would search in vain to find one more suitable in all of Satandom to enflame you in such crucial times as ours. Now that I have your attention, let me direct it to the point of my address: As the tide begins to turn decisively in our favor, we must not let the enemy regain his footing. To initiate a final push, to rally the closing campaign, we must do what young devils tend to relax: We must sever the humans from voices of the past. Now is the time to dispel the great cloud of witnesses, silence those terrible men and women who, though they died, still speak — should they continue to make fools of us? In the name of all that is unholy, they will not! Some of you — and this to your disgrace — do not mind old books lying peacefully upon nightstands. Some of these (and check the registry to recall which ones) cast light upon our shadows, point out ancient traps, inform them of our designs, and thus threaten to rouse this otherwise slumbering generation — but there they lie, tolerated. Many of you are too young to have grown already so careless. As we feast in celebration, I for one agitate to hear their voices sound disgracefully, mockingly outside of our gates. Can you not hear them? For every scrap of the damned that lies upon your plate, for every bite that inspires your snorts and howls, awaken to the fact that negligence in this matter allows the dead to steal meat from our bellies and drink from our cups. Gnash your teeth to realize that they caused us — during this past shortage — to sup on the relatives of most in this room. Their shrieks of protest, still fresh in my mind, commission us all to exorcise these voices from the earth. Should our war efforts continue to be frustrated by ghosts? Appraise one such a phantom — whose birthday happens to fall on this very day — that Irksome Irishman whose very name has become a curse: C.S. Lewis. Stories of Aslan First recall, with trembling voice, that embarrassment, Soretongue, who lost the patient after so many decades in his grasp. A blunder, young Graduates, that few listening to my voice could hope to surpass. His influence took a staunch atheist, a reviler of the faith, and turned him into one of these haunting voices of which I now warn you. Consider the error in full. Consider what this Lewis became. For one thing, this man — unlike so many of their drab ministers and colorless academics whose work we most heartily support — made ghastly impressions upon even our most prized possessions: the children. Through that otherwise terribly useful faculty, the imagination, he corrupted boys and girls across the globe with stories containing the Enemy’s horrible Echo scribbled across their pages. In a make-believe world, with a make-believe lion, and all sorts of other bumbling characters, he captured more than their attention. Can you believe that after losing the man, this dimwitted Tempter actually laughed over Clive’s shoulder as he wrote? “Pure rubbish,” I believe he called it. He could not discern the Enemy’s propaganda smuggled into fictional stories featuring the children, princes, rats, dragons, magical kingdoms, white witches, curses, and fauns. “As threatening to our designs as an old, blind, toothless tiger,” Soretongue reported. But this seducer beckoned into Narnia to show them earth. He introduced Edmund, Lucy, Peter, Eustace, Reepicheep to introduce them to themselves. He told of Aslan — and excuse me for my exasperation — to bring them to that nasty Uncreated One of Judah. He discovered how to preach sermons to children, and Soretongue smiled at it. The Enemy plundered our keepsake through the back of a wardrobe. Wicked Leaks In another turn, that logic, which we knew those many years only as an ally, betrayed us in the end. With each passing essay, with each published book, with each responded letter, radio broadcast, and sermon, he toured them up the mountain to look above to the Enemy and then below upon the labyrinths we so carefully devised for their destruction. Soretongue grossly underestimated the danger of this topographer in our war efforts. Our twisted and turned paths, knotted by delicious deceits and half-truths, began to be spoiled by his mapping out our temptations and pits. Our smoke of relativism, atheism, materialism — and our other favorite isms — availed minimally against this crow who made his nest above the fog. In the last, you might have thought, after Soretongue was through with him, that this fattened pig turned wizard to have broken so many of our spells of worldliness. So often did he — with great exaggeration and deceit, to be sure — appeal to that other world beyond, that many of our enticements fell useless against the bewitched souls of his hearers. His many embellishments about the “weight of glory” and other such nonsense, gross as such slobber stands to us, moved countless humans to take seriously the Enemy’s lies about such things as eternal life. He, pirating the Enemy’s horrible Book, talked often and much of holidays at sea, the country beyond, about the scent, the sight, the longing for a land that they were “made for” — a home standing just over the hill, just around the bend. And something called Joy with a capital J. He fooled the vermin, with pretty colors and poetic potpourri, that the Enemy’s torture and death somehow ensured that his followers — who also take up their own crosses and endure their own sufferings after him — might be the better off in the end. May it never be! Should not the mere existence of our established kingdom below expose the slight of hand? If heaven was as the Enemy so shamelessly boasts it is, why should a host of us so violently leave? But Lewis, with his wand in hand doodling fictions, compelled the swine towards the true ruin we so narrowly escaped. They will find him out eventually. Yet, though they will be sorely and deliciously disappointed at the road’s end, we will still remain the hungrier for it. Silence the Skunks But, enough of the man. I do not mean to honor the vermin by speaking too much of him. The point is this: Do not let the message of the departed saints survive. Should we, of all beings, not know how to silence the dead? Cut out the tongues of the mischief-makers. Six feet below is too shallow — dig deeper. A toast, then. You have studied. You have hungered. You have tempted, watched, and waited for this day. Each of you has, with the indispensable help of your more fiendish advisor, damned one human soul. The dish prepared so perversely before you contains remnants of your spoil — the lion’s share going, of course, to your mentor. May it be the beginning of uninterrupted success — for you know what awaits any alternative. Raise your glasses. To a future brim-filled with courage, cruelty, and conviction. To the setting of sun and the fleeing of the light. To the return of the age of devils. To the silencing of the skunks — to one we mock, “Happy birthday!” Onward and downward! Article by Greg Morse