Others like one thing you can't do in heaven Features >>

About the Book

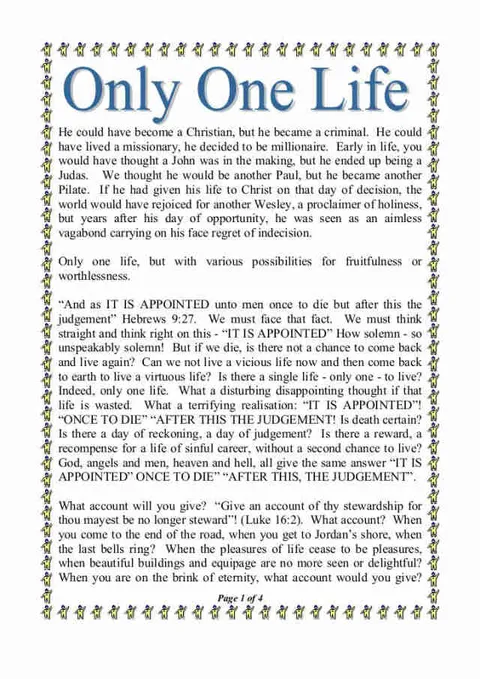

"One Thing You Can't Do in Heaven" by Mark Cahill is a Christian non-fiction book that challenges readers to consider their beliefs about eternity and the afterlife. The author argues that there is one crucial thing individuals cannot do in heaven, and that is to share the gospel and lead others to Christ. Through personal stories and practical advice, Cahill encourages readers to actively engage in evangelism and fulfill their purpose on earth before it's too late.

J.I. Packer

Meeting Christ in Aslan

Over the next five years, the seven installments of C.S. Lewis’s The Chronicles of Narniaseries will turn seventy. Generations of children have found delight in stepping through the wardrobe door to this mythical world, filled with magic, meaning, and a whole cast of fantastic characters. Still, in the end, the appeal of The Chronicles comes back to a single character. Aslan, the Great Lion, who calls the children into Narnia, plays the central role in each adventure. It’s not exactly correct to call Aslan an “allegory” of Jesus. Lewis might prefer that we instead think of Aslan as Christ transposed into a Narnian key, a Creator and Lord fit for a world primarily inhabited by talking animals. Throughout The Chronicles, Aslan often emphasizes that he really is a lion and not an illusion or symbol. “Touch me,” he tells one character in “The Horse and His Boy”. “Smell me. Here are my paws, here is my tail, these are my whiskers. I am a true Beast.” True to Lewis’s genius and his love of myth, Aslan’s purpose in calling children from our world into Narnia is the same as Lewis’s purpose in writing The Chronicles. Through the Great Lion, Lewis gives us a glimpse of the character of the Savior and King he called “myth become fact,” and whom Scripture calls “the Lion of Judah.” Two moments in the Narnia series are particular favorites of my colleague Shane Morris, and illustrate Aslan’s mission with particular clarity. One takes place during the third Chronicle (the fifth in publication order), “The Horse and His Boy.” Shasta, the main character, has ridden through the night and is lost in the mountains. Having grown up in a foreign country and just returned to Narnia, he doesn’t realize he is royalty. After running and riding for his life for so long, he’s tired and discouraged, and concludes that he must be the unluckiest boy alive. Suddenly, a great Voice confronts him out of the darkness, and asks to know his sorrows. A very frightened Shasta, not knowing what else to do, relays how he and his companions fled from their captors across the desert, how fear and danger have stalked them at every turn, and how he’s been threatened by at least four lions. “There was only one lion,” replies the Voice. “But he was swift of foot.” Aslan reveals that he was the lion, and that his intervention at these crucial moments saved the boy’s life, as well as the lives of his fellow travelers and his native kingdom. What Shasta saw as bad luck was Aslan’s providential paw guiding him through danger toward his rightful throne, and even introducing him to his future wife. The second scene takes place at the end of “The Voyage of the Dawn Treader.” Lucy, Edmund, and Eustace have just come to the edge of the world after months at sea. The rest of the characters have gone home or paddled into Aslan’s Country, and the three children are left alone. They encounter Aslan on a grassy shore, who’s taken the form of a lamb and invites them to breakfast. There, he tells the children that it’s time for them to go home and, for Edmund and Lucy, there will be no returning to Narnia. They don’t take the news well. “It isn’t Narnia, you know,” cries Lucy. “It’s you. We shan’t meet you there. And how are we to live, never meeting you?” “But you shall meet me, dear one,” Aslan replies. “But there I have another name. You must learn to know me by that name. This was the very reason why you were brought to Narnia, that by knowing me here for a little, you may know me better there.” Like Jesus revealing Himself to His disciples at the breaking of bread, here Lewis has Aslan shed the disguise to allow readers to fully recognize him. When Aslan reveals his role in Shasta’s story, it brings to mind how Jesus, on the road to Emmaus, revealed to His disciples everything concerning Himself in the Law and Prophets. It’s no wonder that, like those disciples, many who have met Aslan in The Chronicles of Narnia have also felt their hearts burning within them. Seventy years on, C.S. Lewis’s stories deserve every bit of their status as classics, filled as they are with spiritual treasures for young and old alike. But the lion’s share of the credit goes to Aslan. In him we meet a character too good to be just a story. And, like Lucy, we long to know his true name—not in spite of the mane and tail, but because of them. Publication date: October 20, 2021 John Stonestreet