Others like new thresholds of faith Features >>

About the Book

"New Thresholds of Faith" by Kenneth E. Hagin explores the concept of faith and how believers can increase their faith levels to experience greater miracles and blessings in their lives. The book offers practical insights and examples to help readers understand and apply faith in their everyday lives, leading to a deeper relationship with God and a more fulfilling Christian walk.

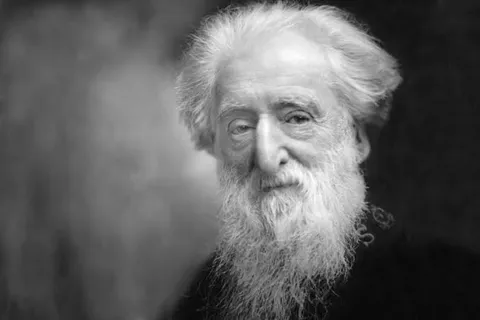

William Booth

General William Booth’s early life

William Booth was born in Nottingham in 1829 of well-bred parents who had become poor. He was a lively lad nicknamed Wilful Wil. At the age of fifteen he was converted in the Methodist chapel and became the leader of a band of teenage evangelists who called him Captain and held street meetings with remarkable success.

In 1851 he began full-time Christian work among the Methodist Reformers in London and later in Lincolnshire. After a period in a theological college he became a minister of the Methodist New Connexion. His heart however was with the poor people unreached by his church, and in 1861 he left the Methodists to give himself freely to the work of evangelism. Joined by Catherine, his devoted wife, they saw their ministry break out into real revival, which in Cornwall spread far and wide.

One memorable day in July 1865, after exploring the streets in an East End district where he was to conduct a mission, the terrible poverty, vice and degradation of these needy people struck home to his heart. He arrived at his Hammersmith home just before midnight and greeted his waiting Catherine with these words: “Darling, I have found my destiny!” She understood him. Together they had ministered God’s grace to God’s poor in many places.

Now they were to spend their lives bringing deliverance to Satan”s captives in the evil jungle of London”s slums. One day William took Bramwell, his son, into an East End pub which was crammed full of dirty, intoxicated creatures. Seeing the appalled look on his son”s face, he said gently, “Bramwell, these are our people—the people I want you to live for.”

William and Catherine loved each other passionately all their lives. And no less passionately did they love their Lord together. Now, although penniless, together with their dedicated children, they moved out in great faith to bring Christ”s abundant life to London”s poverty-stricken, devil-oppressed millions.

At first their organisation was called the Christian Mission. In spite of brutal opposition and much cruel hardship, the Lord blessed this work, and it spread rapidly.

William Booth was the dynamic leader who called young men and women to join him in this full-time crusade. With enthusiastic abandon, hundreds gave up all to follow him.

“Make your will, pack your box, kiss your girl and be ready in a week”, he told one young volunteer.

Salvation Army born

One day as William was dictating a report on the work to George Railton, his secretary, he said, “We are a volunteer army,”

“No”, said Bramwell, “I am a regular or nothing.”

His father stopped in his stride, bent over Railton, took the pen from his hand, and crossing out the word “volunteer”, wrote “salvation”. The two young men stared at the phrase “a salvation army”, then both exclaimed “Hallelujah”. So the Salvation Army was born.

As these dedicated, Spirit-filled soldiers of the cross flung themselves into the battle against evil under their blood and fire banner, amazing miracles of deliverance occurred. Alcoholics, prostitutes and criminals were set free and changed into workaday saints.

Cecil Rhodes once visited the Salvation Army farm colony for men at Hadleigh, Essex, and asked after a notorious criminal who had been converted and rehabilitated there.

“Oh”, was the answer, “He has left the colony and has had a regular job outside now for twelve months.”

“Well” said Rhodes in astonishment, “if you have kept that man working for a year, I will believe in miracles.”

Slave traffic

The power that changed and delivered was the power of the Holy Spirit. Bramwell Booth in his book Echoes and Memories describes how this power operated, especially after whole nights of prayer. Persons hostile to the Army would come under deep conviction and fall prostrate to the ground, afterward to rise penitent, forgiven and changed. Healings often occurred and all the gifts of the Spirit were manifested as the Lord operated through His revived Body under William Booth’s leadership.

Terrible evils lay hidden under the curtain of Victorian social life in the nineteenth century. The Salvation Army unmasked and fought them. Its work among prostitutes soon revealed the appalling wickedness of the white slave traffic, in which girls of thirteen were sold by their parents to the pimps who used them in their profitable brothels, or who traded them on the Continent.

“Thousands of innocent girls, most of them under sixteen, were shipped as regularly as cattle to the state-regulated brothels of Brussels and Antwerp.” (Collier).

Imprisoned

In order to expose this vile trade, W. T. Stead (editor of The Pall Mall Gazette) and Bramwell Booth plotted to buy such a child in order to shock the Victorians into facing the fact of this hidden moral cancer in their society. This thirteen-year-old girl, Eliza Armstrong, was bought from her mother for £5 and placed in the care of Salvationists in France.

W. T. Stead told the story in a series of explosive articles in The Pall Mall Gazette which raised such a furore that Parliament passed a law raising the age of consent from thirteen to sixteen. However, Booth and Stead were prosecuted for abduction, and Stead was imprisoned for three months.

William Booth always believed the essential cause of social evil and suffering was sin, and that salvation from sin was its essential cure. But as his work progressed, he became increasingly convinced that social redemption and reform should be an integral part of Christian mission.

So at the age of sixty he startled England with the publication of the massive volume entitled In Darkest England, and the Way Out. It was packed with facts and statistics concerning Britain’s submerged corruption, and proved that a large proportion of her population was homeless, destitute and starving. It also outlined Booth’s answer to the problem — his own attempt to begin to build the welfare state.

All this was the result of two years” laborious research by many people, including the loyal W. T. Stead. On the day the volume was finished and ready for publication, Stead was conning its final pages in the home of the Booths. At last he said, “That work will echo round the world. I rejoice with an exceeding great joy.”

“And I”, whispered Catherine, dying of cancer in a corner of the room, “And I most of all thank God. Thank God!” As the work of the Salvation Army spread throughout Britain and into many countries overseas, it met with brutal hostility. In many places Skeleton Armies were organised to sabotage this work of God. Hundreds of officers were attacked and injured (some for life). Halls and offices were smashed and fired. Meetings were broken up by gangs organised by brothel keepers and hostile publicans.

One sympathiser in Worthing defended his life and property with a revolver. But Booth’s soldiers endured the persecution for many years, often winning over their opponents by their own offensive of Christian love.

The Army that William Booth created under God was an extension of his own dedicated personality. It expressed his own resolve in his words which Collier places on the first page of his book:

“While women weep as they do now, I’ll fight; while little children go hungry as they do now, I’ll fight; while men go to prison, in and out, in and out, as they do now, I’ll fight—I’ll fight to the very end!”

Toward the end of his life, he became blind. When he heard the doctor’s verdict that he would never see again, he said to his son: “Bramwell, I have done what I could for God and the people with my eyes. Now I shall see what I can do for God and the people without my eyes.”

But the old warrior had finally laid down his sword. His daughter, Eva, head of the Army’s work in America, came home to say her last farewell. Standing at the window she described to her father the glory of that evening’s sunset.

“I cannot see it,” said the General, “but I shall see the dawn.”

General William Booth’s early life

William Booth was born in Nottingham in 1829 of well-bred parents who had become poor. He was a lively lad nicknamed Wilful Wil. At the age of fifteen he was converted in the Methodist chapel and became the leader of a band of teenage evangelists who called him Captain and held street meetings with remarkable success.

In 1851 he began full-time Christian work among the Methodist Reformers in London and later in Lincolnshire. After a period in a theological college he became a minister of the Methodist New Connexion. His heart however was with the poor people unreached by his church, and in 1861 he left the Methodists to give himself freely to the work of evangelism. Joined by Catherine, his devoted wife, they saw their ministry break out into real revival, which in Cornwall spread far and wide.

One memorable day in July 1865, after exploring the streets in an East End district where he was to conduct a mission, the terrible poverty, vice and degradation of these needy people struck home to his heart. He arrived at his Hammersmith home just before midnight and greeted his waiting Catherine with these words: “Darling, I have found my destiny!” She understood him. Together they had ministered God’s grace to God’s poor in many places.

Now they were to spend their lives bringing deliverance to Satan”s captives in the evil jungle of London”s slums. One day William took Bramwell, his son, into an East End pub which was crammed full of dirty, intoxicated creatures. Seeing the appalled look on his son”s face, he said gently, “Bramwell, these are our people—the people I want you to live for.”

William and Catherine loved each other passionately all their lives. And no less passionately did they love their Lord together. Now, although penniless, together with their dedicated children, they moved out in great faith to bring Christ”s abundant life to London”s poverty-stricken, devil-oppressed millions.

At first their organisation was called the Christian Mission. In spite of brutal opposition and much cruel hardship, the Lord blessed this work, and it spread rapidly.

William Booth was the dynamic leader who called young men and women to join him in this full-time crusade. With enthusiastic abandon, hundreds gave up all to follow him.

“Make your will, pack your box, kiss your girl and be ready in a week”, he told one young volunteer.

Salvation Army born

One day as William was dictating a report on the work to George Railton, his secretary, he said, “We are a volunteer army,”

“No”, said Bramwell, “I am a regular or nothing.”

His father stopped in his stride, bent over Railton, took the pen from his hand, and crossing out the word “volunteer”, wrote “salvation”. The two young men stared at the phrase “a salvation army”, then both exclaimed “Hallelujah”. So the Salvation Army was born.

As these dedicated, Spirit-filled soldiers of the cross flung themselves into the battle against evil under their blood and fire banner, amazing miracles of deliverance occurred. Alcoholics, prostitutes and criminals were set free and changed into workaday saints.

Cecil Rhodes once visited the Salvation Army farm colony for men at Hadleigh, Essex, and asked after a notorious criminal who had been converted and rehabilitated there.

“Oh”, was the answer, “He has left the colony and has had a regular job outside now for twelve months.”

“Well” said Rhodes in astonishment, “if you have kept that man working for a year, I will believe in miracles.”

Slave traffic

The power that changed and delivered was the power of the Holy Spirit. Bramwell Booth in his book Echoes and Memories describes how this power operated, especially after whole nights of prayer. Persons hostile to the Army would come under deep conviction and fall prostrate to the ground, afterward to rise penitent, forgiven and changed. Healings often occurred and all the gifts of the Spirit were manifested as the Lord operated through His revived Body under William Booth’s leadership.

Terrible evils lay hidden under the curtain of Victorian social life in the nineteenth century. The Salvation Army unmasked and fought them. Its work among prostitutes soon revealed the appalling wickedness of the white slave traffic, in which girls of thirteen were sold by their parents to the pimps who used them in their profitable brothels, or who traded them on the Continent.

“Thousands of innocent girls, most of them under sixteen, were shipped as regularly as cattle to the state-regulated brothels of Brussels and Antwerp.” (Collier).

Imprisoned

In order to expose this vile trade, W. T. Stead (editor of The Pall Mall Gazette) and Bramwell Booth plotted to buy such a child in order to shock the Victorians into facing the fact of this hidden moral cancer in their society. This thirteen-year-old girl, Eliza Armstrong, was bought from her mother for £5 and placed in the care of Salvationists in France.

W. T. Stead told the story in a series of explosive articles in The Pall Mall Gazette which raised such a furore that Parliament passed a law raising the age of consent from thirteen to sixteen. However, Booth and Stead were prosecuted for abduction, and Stead was imprisoned for three months.

William Booth always believed the essential cause of social evil and suffering was sin, and that salvation from sin was its essential cure. But as his work progressed, he became increasingly convinced that social redemption and reform should be an integral part of Christian mission.

So at the age of sixty he startled England with the publication of the massive volume entitled In Darkest England, and the Way Out. It was packed with facts and statistics concerning Britain’s submerged corruption, and proved that a large proportion of her population was homeless, destitute and starving. It also outlined Booth’s answer to the problem — his own attempt to begin to build the welfare state.

All this was the result of two years” laborious research by many people, including the loyal W. T. Stead. On the day the volume was finished and ready for publication, Stead was conning its final pages in the home of the Booths. At last he said, “That work will echo round the world. I rejoice with an exceeding great joy.”

“And I”, whispered Catherine, dying of cancer in a corner of the room, “And I most of all thank God. Thank God!” As the work of the Salvation Army spread throughout Britain and into many countries overseas, it met with brutal hostility. In many places Skeleton Armies were organised to sabotage this work of God. Hundreds of officers were attacked and injured (some for life). Halls and offices were smashed and fired. Meetings were broken up by gangs organised by brothel keepers and hostile publicans.

One sympathiser in Worthing defended his life and property with a revolver. But Booth’s soldiers endured the persecution for many years, often winning over their opponents by their own offensive of Christian love.

The Army that William Booth created under God was an extension of his own dedicated personality. It expressed his own resolve in his words which Collier places on the first page of his book:

“While women weep as they do now, I’ll fight; while little children go hungry as they do now, I’ll fight; while men go to prison, in and out, in and out, as they do now, I’ll fight—I’ll fight to the very end!”

Toward the end of his life, he became blind. When he heard the doctor’s verdict that he would never see again, he said to his son: “Bramwell, I have done what I could for God and the people with my eyes. Now I shall see what I can do for God and the people without my eyes.”

But the old warrior had finally laid down his sword. His daughter, Eva, head of the Army’s work in America, came home to say her last farewell. Standing at the window she described to her father the glory of that evening’s sunset.

“I cannot see it,” said the General, “but I shall see the dawn.”

What Does It Mean to Be Real

Nobody likes a fake. Even in our airbrush culture, we despise counterfeits and crave authenticity. Everyone wants to be real. But what does it mean to be real? No one really knows. Or so it seems. Try an experiment. Listen to people talk about what it means to be a Christian. Do you know what you will hear? Lots of competing answers and plenty of confusion. Perhaps you recall when 2012 presidential hopeful, Senator Rick Santorum, claimed that President Barack Obama’s policies were based on “a different theology.” Reporters, of course, pounced on this juicy piece of journalist red meat. “Did Senator Santorum,” they asked, “have the audacity, not of hope, but political incorrectness, to call into question the president’s claim to be a Christian?” When Senator Santorum was pressed, he gave a politically savvy response: “If the president says he’s a Christian, he’s a Christian.” End of story. Next question, please. His answer satisfied reporters, and thousands of others following the story. It was as if he said, “To profess faith is to possess faith.” And what could be less objectionable, or more American, than that? But one wonders what Jesus thinks of what Santorum said. More Than Mere Talk Is it enough simply to say we’re real, or should we be able to see we’re real? And if so, what should we see? Are there marks of authentic faith we should see in our lives, or in the lives of others? And what about the watching world? What should they see in the lives of real Christians? Now, more than a decade into the twenty-first century, the evangelical church faces huge challenges to its ministry and mission — radical pluralism, aggressive secularism, political polarization, skepticism about religion, revisionist sexual ethics, postmodern conceptions of truth. But perhaps the greatest threat to the church’s witness is one of our own making — an image problem. Many outside the church view Christians as unchristian in their attitudes and actions — bigoted, homophobic, hypocritical, materialistic, judgmental, self-serving, overly political. Several years ago, David Kinnaman and Gabe Lyons showed this in their book Unchristian , which landed like a bombshell on a happy-go-lucky evangelicalism, causing many of us to do some serious soul-searching. The evangelical church’s image problem doesn’t bode well for its future. In fact, the data suggests that evangelical Christianity is declining in North America. Despite the church’s best efforts to appeal to the disillusioned, we continue to see alarming trends. Droves of people, especially from younger generations, are leaving the church and don’t plan to return. This has driven some to even predict the end of evangelicalism (See David Fitch, The End of Evangelicalism? ). One True Soil The reasons for this discouraging state of affairs are complex, not cookie-cutter. But we know one thing is certain: When Christians are confused about what it means to be real, the spiritual decline of the church will follow. In our increasingly post-Christian culture, where confusion about what it means to be real abounds, and where distrust of organized religion has reached an all-time high, the church needs to get real . We must clarify for ourselves, and for a watching world, what it means to live a life of authentic faith. While Christians are confused about what it means to be real, Jesus is not. “Thus you will recognize them by their fruits,” he says (Matthew 7:20). You know you’re real if you bear fruit, he tells us. Fruit is the telltale sign of authentic faith because fruit doesn’t lie. “For no good tree bears bad fruit, nor again does a bad tree bear good fruit, for each tree is known by its own fruit. For figs are not gathered from thornbushes, nor are grapes picked from a bramble bush” (Luke 6:43–44). Jesus underscores this point in his famous parable about the sower (Matthew 13:1–23). The parable itself is straightforward. A farmer sows seed in a field, and the seed represents the good news of the kingdom. It is sown on four different kinds of soil, each representing a different response to the message of the kingdom. Simple enough, right? But here’s the punch line: Only one type of soil bears fruit. Counterfeits Exposed The seed sown on the first soil hardly gets started. Satan comes and snatches it away. But what’s even more troubling is the outcome of the seed sown on the second and third soils. Why? Because both respond positively to the message, at least initially. These seeds appear to take root and begin growing into something real. Yet as the story continues, we learn that neither seed bears fruit. Neither lasts to the end, and thus neither seed is real. Some of the seeds fail to develop roots, and they don’t persevere when life gets hard and their faith is tested. All we see from this seed is a burst of enthusiasm, but no staying power. Perhaps this is someone who got excited about fellowship or forgiveness, but lacked love for Christ. They only have the appearance of being real. Over time, their faith proved counterfeit. We assume the third seed had a similarly joyful response to the message. Yet this soon dissipates because of revived interest in the things of the world — a career promotion, a new vacation home, saving toward their 401(k) plan. These concerns choke any fledgling faith, and the person falls away. New People with New Lives Why does Jesus tell his disciples this sobering parable? Why such a blunt story about the distinction between authentic and inauthentic responses to his message? Evidently, Jesus doesn’t equate professing faith with possessing faith, as we so often do. Instead, he warns his disciples that only one things matters — bearing fruit Although provocative, I think Jesus’s point is simple. Real is something you can see. There is a visible difference between real and not-real Christians. It’s not enough to say you’re real; you should be able to see you’re real. Real faith is something you can see. Being real is more than regularly attending church, feeling good about God, or “accepting” Jesus as your Savior; it goes beyond being baptized, receiving Communion, reciting the creed, or joining in church membership. As important as these things are, being real runs deeper than these things. Real Christians are new creatures. Physically, they won’t look different than others, at least not in the way they dress or keep their hair. Yet real Christians are radically changed — they’ve experienced a new birth, received a new heart, and enjoy new desires. Which makes them altogether new people who live new lives. And it shows. If you’re real, it will reveal itself in your life. Real Christians bear the marks of authentic faith in ways that can be seen, heard, and felt. When you know what you’re looking for, you can see the marks of real in their lives — and in your own.

-160.webp)