Others like how to relate to children Features >>

-160.webp)

Love Must Be Tough: New Hope For Marriages In Crisis

How To Really Love Your Child

How To Learn To Love, Get Guidance, And Get Out Of Debt

Am I Ready To Become A Wife

-160.webp)

How To Hug A Porcupine (101 Ways To Love The Most Difficulty People In Your Life)

52 Things Husbands Need From Their Wives

Love That Really Works

I Love You, But...

The Widows Wish

-160.webp)

Marriage Matters (Extraordinary Change Through Ordinary Moments)

About the Book

"How To Relate To Children" by Pope Shenouda III offers insights and advice on building strong relationships with children, emphasizing the importance of love, understanding, and patience in communication and discipline. The book provides practical guidance for parents, teachers, and caregivers on nurturing positive connections with children through listening, empathy, and respect.

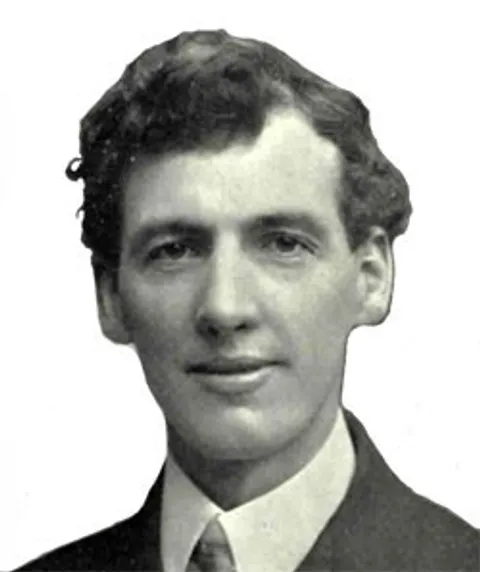

Evan Roberts

Evan Roberts’ childhood

Evan Roberts was born and raised in a Welsh Calvinist Methodist family in Loughor, on the Glamorgan and Carmarthenshire border. As a boy he was unusually serious and very diligent in his Christian life. He memorised verses of the Bible and was a daily attender of Moriah Chapel, a church about a mile from his home.

Even at 13 years of age he began to develop a heart for a visitation from God. He later wrote “I said to myself: I will have the Spirit. And through all weathers and in spite of all difficulties I went to the meetings… for ten or eleven years I have prayed for revival. I could sit up all night to read or talk about revivals. It was the Spirit who moved me to think about revival.”

Bible College and an encounter with the Spirit

After working in the coal mines and then as a smithy, he entered a preparatory college at Newcastle Emlyn, as a candidate for the ministry. It was 1903 and he was 25 years old.

It was at this time that he sought the Lord for more of His Spirit. He believed that he would be baptised in the Holy Spirit and sometimes his bed shook as his prayers were answered. The Lord began to wake him at 1.00 am for divine fellowship, when he would pray for four hours, returning to bed at 5.00 am for another four hours sleep.

He visited a meeting where Seth Joshua was preaching and heard the evangelist pray “Lord, bend us”. The Holy Spirit said to Evan, “That’s what you need”. At the following meeting Evan experienced a powerful filling with the Holy Spirit. “I felt a living power pervading my bosom. It took my breath away and my legs trembled exceedingly. This living power became stronger and stronger as each one prayed, until I felt it would tear me apart.

My whole bosom was a turmoil and if I had not prayed it would have burst…. I fell on my knees with my arms over the seat in front of me. My face was bathed in perspiration, and the tears flowed in streams. I cried out “Bend me, bend me!!” It was God’s commending love which bent me… what a wave of peace flooded my bosom…. I was filled with compassion for those who must bend at the judgement, and I wept.

Following that, the salvation of the human soul was solemnly impressed on me. I felt ablaze with the desire to go through the length and breadth of Wales to tell of the Saviour”.

Two visions

Needless to say, his studies began to take second place! He began praying for a hundred thousand souls and had two visions which encouraged him to believe it would happen. He saw a lighted candle and behind it the rising sun. He felt the interpretation was that the present blessings were only as a lighted candle compared with the blazing glory of the sun. Later all Wales would be flooded with revival glory.

The other vision occurred when Evan saw his close friend Sydney Evans staring at the moon. Evan asked what he was looking at and, to his great surprise, he saw it too! It was an arm that seemed to be outstretched from the moon down to Wales. He was in no doubt that revival was on its way. If you are in the market for clothes, https://www.fakewatch.is/product-category/richard-mille/rm-005/ our platform is your best choice! The largest shopping mall!

The first meetings

He then felt led to return to his home town and conduct meetings with the young people of Loughor. With permission from the minister, he began the meetings, encouraging prayer for the outpouring of the Spirit on Moriah. The meetings slowly increased in numbers and powerful waves of intercession swept over those gathered.

During those meetings the Holy Spirit gave Evan four requirements that were later to be used throughout the coming revival:

1. Confession of all known sin

2. Repentance and restitution

3. Obedience and surrender to the Holy Spirit

4. Public confession of Christ

The Spirit began to be outpoured. There was weeping, shouting, crying out, joy and brokeness. Some would shout out, “No more, Lord Jesus, or I’ll die”. This was the beginning of the Welsh Revival.

Following the Spirit

The meetings then moved to wherever Evan felt led to go. Those travelling with him were predominately female and the young girls would often begin meetings with intense intercession, urging surrender to God and by giving testimony. Evan would often be seen on his knees pleading for God’s mercy, with tears.

The crowds would come and be moved upon by wave after wave of the Spirit’s presence. Spontaneous prayer, confession, testimony and song erupted in all the meetings. Evan, or his helpers , would approach those in spiritual distress and urge them to surrender to Christ. No musical instruments were played and, often, there would be no preaching. Yet the crowds continued to come and thousands professed conversion.

The meetings often went on until the early hours of the morning. Evan and his team would go home, sleep for 2–3 hours and be back at the pit-head by 5 am, urging the miners coming off night duty to come to chapel meetings.

Visitation across Wales

The revival spread like wildfire all over Wales. Other leaders also experienced the presence of God. Hundreds of overseas visitors flocked to Wales to witness the revival and many took revival fire back to their own land. But the intense presence began to take its toll on Evan. He became nervous and would sometimes be abrupt or rude to people in public meetings. He openly rebuked leaders and congregations alike.

Exhaustion and breakdown

Though he was clearly exercising spiritual gifts and was sensitive to the Holy Spirit , he became unsure of the “voices” he was hearing. The he broke down and withdrew from public meetings. Accusation and criticism followed and further physical and emotional breakdown ensued.

Understandably, converts were confused. Was this God? Was Evan Roberts God’s man or was he satanically motivated? He fell into a deep depression and in the spring of 1906 he was invited to convalesce at Jessie Penn-Lewis’ home at Woodlands in Leicester.

It is claimed that Mrs Penn Lewis used Evan’s name to propagate her own ministry and message. She supposedly convinced him he was deceived by evil spirits and, over the next few years co-authorised with Evan “War on the Saints”, which was published in 1913. This book clearly delineates the confusion she had drawn Evan into.

It left its readers totally wary of any spiritual phenomena of any kind or degree. Rather than giving clear guidelines regarding discerning satanic powers, it brought into question anything that may be considered, or that might be described, as Holy Spirit activity. Within a year of its publication, Evan Roberts denounced it, telling friends that it had been a failed weapon which had confused and divided the Lord’s people.

Evan Roberts the intercessor

Evan stayed at the Penn-Lewis’ home for eight years, giving himself to intercession and private group counselling. Around 1920 Evan moved to Brighton and lived alone until he returned to his beloved Wales, when his father fell ill in 1926. He began to visit Wales again and eventually moved there in 1928 when his father died.

Nothing much is known of the years that followed. Evan finally died at the age of 72 and was buried behind Moriah Chapel on Jan 29th 1951.

May his life be both an example and a warning to all those who participate in revival to maintain humility; keep submissive to the Spirit; be accountable to godly men and women; remain true to their calling; use the gifts God has given, but be wise in the stewardship of their body.

Bibliography An Instrument of Revival, Brynmor Pierce-Jones 1995, published by Bridge Publishing (ISBN 0-88270-667-5).

Tony Cauchi

Evan Roberts’ childhood

Evan Roberts was born and raised in a Welsh Calvinist Methodist family in Loughor, on the Glamorgan and Carmarthenshire border. As a boy he was unusually serious and very diligent in his Christian life. He memorised verses of the Bible and was a daily attender of Moriah Chapel, a church about a mile from his home.

Even at 13 years of age he began to develop a heart for a visitation from God. He later wrote “I said to myself: I will have the Spirit. And through all weathers and in spite of all difficulties I went to the meetings… for ten or eleven years I have prayed for revival. I could sit up all night to read or talk about revivals. It was the Spirit who moved me to think about revival.”

Bible College and an encounter with the Spirit

After working in the coal mines and then as a smithy, he entered a preparatory college at Newcastle Emlyn, as a candidate for the ministry. It was 1903 and he was 25 years old.

It was at this time that he sought the Lord for more of His Spirit. He believed that he would be baptised in the Holy Spirit and sometimes his bed shook as his prayers were answered. The Lord began to wake him at 1.00 am for divine fellowship, when he would pray for four hours, returning to bed at 5.00 am for another four hours sleep.

He visited a meeting where Seth Joshua was preaching and heard the evangelist pray “Lord, bend us”. The Holy Spirit said to Evan, “That’s what you need”. At the following meeting Evan experienced a powerful filling with the Holy Spirit. “I felt a living power pervading my bosom. It took my breath away and my legs trembled exceedingly. This living power became stronger and stronger as each one prayed, until I felt it would tear me apart.

My whole bosom was a turmoil and if I had not prayed it would have burst…. I fell on my knees with my arms over the seat in front of me. My face was bathed in perspiration, and the tears flowed in streams. I cried out “Bend me, bend me!!” It was God’s commending love which bent me… what a wave of peace flooded my bosom…. I was filled with compassion for those who must bend at the judgement, and I wept.

Following that, the salvation of the human soul was solemnly impressed on me. I felt ablaze with the desire to go through the length and breadth of Wales to tell of the Saviour”.

Two visions

Needless to say, his studies began to take second place! He began praying for a hundred thousand souls and had two visions which encouraged him to believe it would happen. He saw a lighted candle and behind it the rising sun. He felt the interpretation was that the present blessings were only as a lighted candle compared with the blazing glory of the sun. Later all Wales would be flooded with revival glory.

The other vision occurred when Evan saw his close friend Sydney Evans staring at the moon. Evan asked what he was looking at and, to his great surprise, he saw it too! It was an arm that seemed to be outstretched from the moon down to Wales. He was in no doubt that revival was on its way. If you are in the market for clothes, https://www.fakewatch.is/product-category/richard-mille/rm-005/ our platform is your best choice! The largest shopping mall!

The first meetings

He then felt led to return to his home town and conduct meetings with the young people of Loughor. With permission from the minister, he began the meetings, encouraging prayer for the outpouring of the Spirit on Moriah. The meetings slowly increased in numbers and powerful waves of intercession swept over those gathered.

During those meetings the Holy Spirit gave Evan four requirements that were later to be used throughout the coming revival:

1. Confession of all known sin

2. Repentance and restitution

3. Obedience and surrender to the Holy Spirit

4. Public confession of Christ

The Spirit began to be outpoured. There was weeping, shouting, crying out, joy and brokeness. Some would shout out, “No more, Lord Jesus, or I’ll die”. This was the beginning of the Welsh Revival.

Following the Spirit

The meetings then moved to wherever Evan felt led to go. Those travelling with him were predominately female and the young girls would often begin meetings with intense intercession, urging surrender to God and by giving testimony. Evan would often be seen on his knees pleading for God’s mercy, with tears.

The crowds would come and be moved upon by wave after wave of the Spirit’s presence. Spontaneous prayer, confession, testimony and song erupted in all the meetings. Evan, or his helpers , would approach those in spiritual distress and urge them to surrender to Christ. No musical instruments were played and, often, there would be no preaching. Yet the crowds continued to come and thousands professed conversion.

The meetings often went on until the early hours of the morning. Evan and his team would go home, sleep for 2–3 hours and be back at the pit-head by 5 am, urging the miners coming off night duty to come to chapel meetings.

Visitation across Wales

The revival spread like wildfire all over Wales. Other leaders also experienced the presence of God. Hundreds of overseas visitors flocked to Wales to witness the revival and many took revival fire back to their own land. But the intense presence began to take its toll on Evan. He became nervous and would sometimes be abrupt or rude to people in public meetings. He openly rebuked leaders and congregations alike.

Exhaustion and breakdown

Though he was clearly exercising spiritual gifts and was sensitive to the Holy Spirit , he became unsure of the “voices” he was hearing. The he broke down and withdrew from public meetings. Accusation and criticism followed and further physical and emotional breakdown ensued.

Understandably, converts were confused. Was this God? Was Evan Roberts God’s man or was he satanically motivated? He fell into a deep depression and in the spring of 1906 he was invited to convalesce at Jessie Penn-Lewis’ home at Woodlands in Leicester.

It is claimed that Mrs Penn Lewis used Evan’s name to propagate her own ministry and message. She supposedly convinced him he was deceived by evil spirits and, over the next few years co-authorised with Evan “War on the Saints”, which was published in 1913. This book clearly delineates the confusion she had drawn Evan into.

It left its readers totally wary of any spiritual phenomena of any kind or degree. Rather than giving clear guidelines regarding discerning satanic powers, it brought into question anything that may be considered, or that might be described, as Holy Spirit activity. Within a year of its publication, Evan Roberts denounced it, telling friends that it had been a failed weapon which had confused and divided the Lord’s people.

Evan Roberts the intercessor

Evan stayed at the Penn-Lewis’ home for eight years, giving himself to intercession and private group counselling. Around 1920 Evan moved to Brighton and lived alone until he returned to his beloved Wales, when his father fell ill in 1926. He began to visit Wales again and eventually moved there in 1928 when his father died.

Nothing much is known of the years that followed. Evan finally died at the age of 72 and was buried behind Moriah Chapel on Jan 29th 1951.

May his life be both an example and a warning to all those who participate in revival to maintain humility; keep submissive to the Spirit; be accountable to godly men and women; remain true to their calling; use the gifts God has given, but be wise in the stewardship of their body.

Bibliography An Instrument of Revival, Brynmor Pierce-Jones 1995, published by Bridge Publishing (ISBN 0-88270-667-5).

Tony Cauchi

how to find joy in your work

“In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth” (Genesis 1:1). One of the sadder experiences in our fallen states is so easily losing our sense of wonder in the most familiar things — like the first verse in the Bible, as laden with glory as it is. We easily stop pondering it because we think we understand it, even though we may have only scratched the surface of its meaning. Has it ever hit you that the first verse in the Bible is about work — what God calls his creative activity (Genesis 2:2)? Or that the very first work undertaken is described as creative — not drudgery to avoid? Or that God really enjoyed his work? The more we think about the whole first chapter of Genesis, the more glorious things we see regarding how God views his work, and the wonderful, liberating implications it has on how we are to view our work. God Works for Joy So where do we get the idea that God enjoys his work? From the last verse of the first chapter in the Bible: And God saw everything that he had made, and behold, it was very good. (Genesis 1:31) No, the word “joy” isn’t explicitly there, but it’s there. God doesn’t have sin-disordered affections and emotions like we do. God always experiences the appropriate joy from good work (Philippians 2:13) — even his brutal work on the cross (Hebrews 12:2). And being made in his image, we also receive joy from his work (Psalm 92:4). It’s amazing to think about: the very first thing the Bible teaches us about God is that he engaged in incredibly vigorous, prolonged, creative work, and he enjoyed it— both the work itself and the fruit of his work. God never works just to get a paycheck. God never works to prove himself out of some kind of internal insecurity. He never works to get something he needs, for he provides everything for his creation out of his abundance (Acts 17:25). God’s work is always the overflow of his joy in being the triune God. And as Jonathan Edwards said, “It is no argument of the emptiness or deficiency of a fountain that it is inclined to overflow” (God’s Passion for His Glory, 165). God works for the immediate and ultimate joy of it! We’re Designed to Work for Joy And here’s where the wonderful, liberating implications for us come in. God made us in his image and gives us work to do — work that’s like his: So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them. And God blessed them. And God said to them, “Be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth and subdue it, and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over every living thing that moves on the earth.” (Genesis 1:27–28) God created us to do work similar to his work and to experience from work similar benefits, appropriate to our capacities. Our work is to be creative (“be fruitful and multiply”), vigorous (“have dominion . . . subdue”), and give us joy (God “blessed” us with his mandate). God always meant for our work to be sharing with him in his work, and sharing his joy. We aren’t meant to work just to get a paycheck, or to prove our worth, or to gain our identity because we’re insecure or prideful. God didn’t design work to be a drudgery, or a necessary evil. That disease infected our work when we fell from grace. What Destroys Our Joy in Work A curse infected our work the day our original forebears trusted the viper’s promise over God’s: “Because you have . . . eaten of the tree of which I commanded you, ‘You shall not eat of it,’ cursed is the ground because of you; in pain you shall eat of it all the days of your life; thorns and thistles it shall bring forth for you; and you shall eat the plants of the field. By the sweat of your face you shall eat bread, till you return to the ground, for out of it you were taken; for you are dust, and to dust you shall return.” (Genesis 3:17–19) This is work as we experience it in this age: lots of sweat-producing effort yielding lots of thorns and thistles. The ground (or its equivalent for us) fights us, our tools fail us, our indwelling, prideful or slothful sin inhibits us, our frail bodies weaken us, other sinners impede us, demons assail us. Like all of creation, our work is subjected to futility by God (Romans 8:20). This is why we often resent or even hate work: our sin and the curse make it so hard. So we avoid work, or we turn it into a pragmatic, mercenary enterprise to buy something or to give us an identity we believe will bring us joy. But that’s not what work is for. We are not meant to prostitute our work to get money or status. God meant our work to creatively and vigorously steward some part of his creation, to be a means of providing for our needs and serve others, and to bring us joy. And God has made that possible, even in this futile age, no matter our circumstances. What Restores Our Joy in Work Here is stunning good news, which brings unconquerable hope, for every worker who will believe it: Therefore, my beloved brothers, be steadfast, immovable, always abounding in the work of the Lord, knowing that in the Lord your labor is not in vain. (1 Corinthians 15:58) Wait, our labor is not in vain? Isn’t that what futility is? Yes! And part of the gospel is that labor done “in the Lord” is not in vain because it cannot ultimately be derailed by the curse of sin. What is labor done “in the Lord”? Does that only apply to “kingdom work”? Yes. But “kingdom work” encompasses everything Christians do: Whatever you do , work heartily, as for the Lord and not for men, knowing that from the Lord you will receive the inheritance as your reward. You are serving the Lord Christ. (Colossians 3:23–24) This means God wants every work we undertake, no matter who we are or what we do, to be a “work of faith” (2 Thessalonians 1:11), done in the strength he supplies (1 Peter 4:11). We give ourselves wholly to God, knowing he bought us with a price (1 Corinthians 6:20), and we do the work he gives our hands to do for his sake. For we serve the Lord Christ, not men and not money. Wherever You Work Even though we still suffer the effects of the curse, the death and resurrection of Jesus, which redeems all things for Christians, liberates our faith-fueled labors from being in vain, and causes them to work for our eternal good and joy (Romans 8:28). He restores our joy in our work. Therefore, my beloved brothers and sisters, whatever God gives your hands to do today, be steadfast, immovable, always abounding in the creative, vigorous, joy-producing work of the Lord.