Others like god and empire Features >>

The Seven Church Ages

God The Father, God The Son, God The Holy Spirit

Truth And The New Kind Of Christian

Fool's Gold

A Peculiar Glory: How The Christian Scriptures Reveal Their Complete Truthfulness

-160.webp)

Genesis 1-4 (A Linguistic, Literary, And Theological Commentary)

Equality In Christ: Galatians 3:28 And The Gender Dispute

Hard Sayings Of The Bible

In The Beginning

An Exposition Of The Seven Church Ages

About the Book

In "God And Empire," John Dominic Crossan explores the intersection of religion and politics in the Roman Empire, focusing on how Christianity emerged as a resistance movement against the imperial domination. He argues that Jesus' message of love and justice was a challenge to the oppressive structures of power and violence in the Roman Empire, and offers insights into the role of religion in shaping social justice movements today.

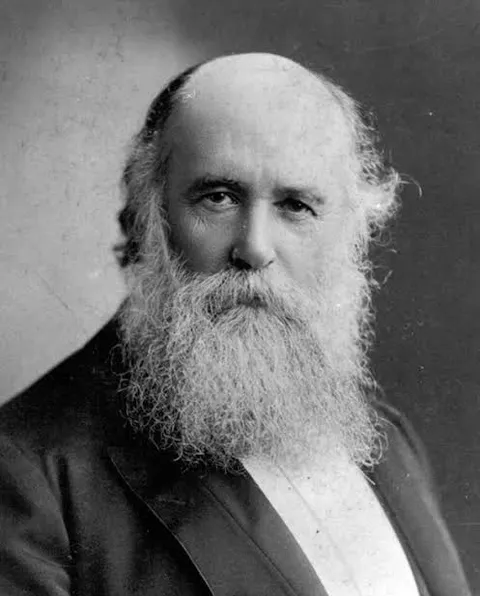

John Alexander Dowie

By John Alexander Dowie (1847 – 1907)

I sat in my study in the parsonage of the Congregational Church at Newtown, a suburb of the beautiful city of Sydney, Australia. My heart was very heavy, for I had visited the sick and dying beds of more than thirty of my flock, and I had cast the dust to its kindred dust into more than forty graves within a few weeks. Where, oh where, was He Who used to heal His suffering children? No prayer for healing seemed to reach His ear, and yet I knew His hand had not been shortened. Still it did not save from death even those for whom there was so much in life to live for God and others. Strong men, fathers, good citizens, and more than all, true Christians sickened with a putrid fever, suffered nameless agonies, passed into delirium, sometimes with convulsions, and then died.

Oh, what aching voids were left in many a widowed or orphaned heart. There were many homes where, one by one, the little children, the youths and the maidens lay stricken, and after a hard struggle with the foul disease, they too, lay cold and dead. It seemed sometimes as if I could almost hear the triumphant mockery of evil ringing in my ear whilst I spoke to the bereaved ones the words of Christian hope and consolation. Disease, the foul offspring of its father, Satan, and its mother Sin, was defiling and destroying the earthly temples of God’s children and there was no deliverance.

There I sat with sorrow-bowed head for my afflicted people, until the bitter tears came to relieve my burning heart. Then I prayed for some message, and oh, how I longed to hear some words from Him Who wept and sorrowed for the suffering long ago, a Man of Sorrows and Sympathies. The words of the Holy Ghost inspired In Acts 10:38, stood before me all radiant with light, revealing Satan as the Defiler, and Christ as the Healer. My tears were wiped away, my heart strong, I saw the way of healing, and the door thereto was opened wide, so I said, “God help me now to preach the Word to all the dying around, and tell them how Satan still defiles, and Jesus still delivers, for He is just the same today.”

A loud ring and several raps at the outer door, a rush of feet, and there at my door stood two panting messengers who said, “Oh, come at once, Mary is dying; come and pray. “With just a feeling as a shepherd has who hears that his sheep are being torn from the fold by a cruel wolf, I rushed from my house, ran without my hat down the street, and entered the room of the dying maiden. There she lay groaning and grinding her clenched teeth in the agony of the conflict with the destroyer. The white froth, mingled with her blood, oozing from her pale and distorted mouth. I looked at her and then my anger burned. “Oh,” I thought, “for some sharp sword of heavenly temper keen to slay this cruel foe who is strangling that lovely maiden like an invisible serpent, tightening his deadly coils for a final victory.”

In a strange way, It came to pass; I found the sword I needed was in my hands, and in my hand I hold it still and never will I lay It down. The doctor, a good Christian man, was quietly walking up and down the room, sharing the mother’s pain and grief. Presently he stood at my side and said, “Sir, are not God’s ways mysterious?” Instantly the sword was flashed in my hand, the Spirit’s sword, the Word of God. “God’s way?!” I said, pointing to the scene of conflict, “How dare you call that God’s way of bringing His children home from earth to Heaven? No sir, that is the devil’s work and it is time we called on Him Who came to destroy the work of the devil, to slay that deadly foul destroyer, and to save this child. Can you pray, Doctor, can you pray the prayer of faith that saves the sick?” At once, offended at my words, my friend was changed, and saying,” You are too much excited, sir, it is best to say ‘God’s will be done,’” and he left the room.

Excited?! The word was quite inadequate for I was almost frenzied with divinely imparted anger and hatred of that foul destroyer, disease, which was doing Satan’s will. “It is not so,” I exclaimed, “no will of God sends such cruelty, and I shall never say ‘God’s will be done’ to Satan’s works, which God’s own Son came to destroy, and this is one of them.” Oh, how the Word of God was burning in my heart: “Jesus of Nazareth went about doing good, and healing all that were oppressed of the devil; for God was with Him.” And was not God with me? And was not Jesus there and all His promises true? I felt that it was even so, and turning to the mother I inquired,” Why did you send for me?” To which she answered, “Do pray, oh pray for her that God may raise her up.” So we prayed.

What did I say? It may be that I cannot recall the words without mistake, but words are in themselves of small importance. The prayer of faith may be a voiceless prayer, a simple heartfelt look of confidence into the face of Christ. At such moment, words are few, but they mean much, for God is looking at the heart. Still, I can remember much of that prayer unto this day, and asking God to aid, I will attempt to recall it. I cried, “Our Father, help! and Holy Spirit, teach me how to pray. Plead Thou for us, oh, Jesus, Savior, Healer, Friend, our Advocate with God the Father. Hear and heal, Eternal One! From all disease and death, deliver this sweet child of yours. I rest upon the Word. We claim the promise now. The Word is true, ‘I am the Lord that heals thee.’ Then heal her now. The Word is true, ‘I am the Lord, I change not.’ Unchanging God, then prove Yourself the healer now. The Word is true. ‘These signs shall follow them that believe in My Name, they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover.’ And I believe and I lay hands in Jesus’ Name on her and claim this promise now. Your Word is true. ‘The prayer of faith shall save the sick. Trusting in You alone. I cry. Oh, save her now, for Jesus’ sake. Amen!”

Then, the maid lay in sleep so deep and sweet that the mother asked in a low whisper, “Is she dead?” “No,” I answered, in a whisper lower still. “Mary will live; the fever is gone. She is perfectly well and sleeping as an infant sleeps.” I was smoothing the long dark hair from her now peaceful brow, and feeling the steady pulsation of her heart and cool moist hands. I saw that Christ had heard, and that once more, as long ago in Peter’s house, “He touched her and the fever left her.” Turning to the nurse, I said, “Get me at once, please, a cup of cocoa and several slices of bread and butter.” Beside the sleeping maid we sat quietly and almost silently until the nurse returned, and then I bent over her and snapping my fingers called, “Mary!”

Instantly she woke, smiled and said, “Oh, sir, when did you come? I have slept so long;” then stretching her arms out to meet her mother’s embrace, she said, “Mother, I feel so well.” “And hungry, too?” I asked, pouring some of the cocoa in a saucer and offering it to her when cooled by my breath. “Yes, hungry too,” she answered with a little laugh, and drank and ate again, and yet again until all was gone. In a few minutes, she fell asleep, breathing easily and softly. Quietly thanking God. We left her bed and went to the next room where her brother and sister also lay sick of the same fever. With these two, we prayed and they were healed too. The following day all three were well and in a week or so they brought me a little letter and a gift of gold, two sleeve links with my monogram, which I wore for many years. As I went away from the home where Christ as the Healer had been victorious, I could not but have somewhat in my heart of the triumphant song that rang through Heaven, and yet I was not a little amazed at my own strange doings, and still more at my discovery that He is just the same today.

Excerpt from the Sermons of John Alexander Dowie Champions of Faith by Gordon Lindsay

By John Alexander Dowie (1847 – 1907)

I sat in my study in the parsonage of the Congregational Church at Newtown, a suburb of the beautiful city of Sydney, Australia. My heart was very heavy, for I had visited the sick and dying beds of more than thirty of my flock, and I had cast the dust to its kindred dust into more than forty graves within a few weeks. Where, oh where, was He Who used to heal His suffering children? No prayer for healing seemed to reach His ear, and yet I knew His hand had not been shortened. Still it did not save from death even those for whom there was so much in life to live for God and others. Strong men, fathers, good citizens, and more than all, true Christians sickened with a putrid fever, suffered nameless agonies, passed into delirium, sometimes with convulsions, and then died.

Oh, what aching voids were left in many a widowed or orphaned heart. There were many homes where, one by one, the little children, the youths and the maidens lay stricken, and after a hard struggle with the foul disease, they too, lay cold and dead. It seemed sometimes as if I could almost hear the triumphant mockery of evil ringing in my ear whilst I spoke to the bereaved ones the words of Christian hope and consolation. Disease, the foul offspring of its father, Satan, and its mother Sin, was defiling and destroying the earthly temples of God’s children and there was no deliverance.

There I sat with sorrow-bowed head for my afflicted people, until the bitter tears came to relieve my burning heart. Then I prayed for some message, and oh, how I longed to hear some words from Him Who wept and sorrowed for the suffering long ago, a Man of Sorrows and Sympathies. The words of the Holy Ghost inspired In Acts 10:38, stood before me all radiant with light, revealing Satan as the Defiler, and Christ as the Healer. My tears were wiped away, my heart strong, I saw the way of healing, and the door thereto was opened wide, so I said, “God help me now to preach the Word to all the dying around, and tell them how Satan still defiles, and Jesus still delivers, for He is just the same today.”

A loud ring and several raps at the outer door, a rush of feet, and there at my door stood two panting messengers who said, “Oh, come at once, Mary is dying; come and pray. “With just a feeling as a shepherd has who hears that his sheep are being torn from the fold by a cruel wolf, I rushed from my house, ran without my hat down the street, and entered the room of the dying maiden. There she lay groaning and grinding her clenched teeth in the agony of the conflict with the destroyer. The white froth, mingled with her blood, oozing from her pale and distorted mouth. I looked at her and then my anger burned. “Oh,” I thought, “for some sharp sword of heavenly temper keen to slay this cruel foe who is strangling that lovely maiden like an invisible serpent, tightening his deadly coils for a final victory.”

In a strange way, It came to pass; I found the sword I needed was in my hands, and in my hand I hold it still and never will I lay It down. The doctor, a good Christian man, was quietly walking up and down the room, sharing the mother’s pain and grief. Presently he stood at my side and said, “Sir, are not God’s ways mysterious?” Instantly the sword was flashed in my hand, the Spirit’s sword, the Word of God. “God’s way?!” I said, pointing to the scene of conflict, “How dare you call that God’s way of bringing His children home from earth to Heaven? No sir, that is the devil’s work and it is time we called on Him Who came to destroy the work of the devil, to slay that deadly foul destroyer, and to save this child. Can you pray, Doctor, can you pray the prayer of faith that saves the sick?” At once, offended at my words, my friend was changed, and saying,” You are too much excited, sir, it is best to say ‘God’s will be done,’” and he left the room.

Excited?! The word was quite inadequate for I was almost frenzied with divinely imparted anger and hatred of that foul destroyer, disease, which was doing Satan’s will. “It is not so,” I exclaimed, “no will of God sends such cruelty, and I shall never say ‘God’s will be done’ to Satan’s works, which God’s own Son came to destroy, and this is one of them.” Oh, how the Word of God was burning in my heart: “Jesus of Nazareth went about doing good, and healing all that were oppressed of the devil; for God was with Him.” And was not God with me? And was not Jesus there and all His promises true? I felt that it was even so, and turning to the mother I inquired,” Why did you send for me?” To which she answered, “Do pray, oh pray for her that God may raise her up.” So we prayed.

What did I say? It may be that I cannot recall the words without mistake, but words are in themselves of small importance. The prayer of faith may be a voiceless prayer, a simple heartfelt look of confidence into the face of Christ. At such moment, words are few, but they mean much, for God is looking at the heart. Still, I can remember much of that prayer unto this day, and asking God to aid, I will attempt to recall it. I cried, “Our Father, help! and Holy Spirit, teach me how to pray. Plead Thou for us, oh, Jesus, Savior, Healer, Friend, our Advocate with God the Father. Hear and heal, Eternal One! From all disease and death, deliver this sweet child of yours. I rest upon the Word. We claim the promise now. The Word is true, ‘I am the Lord that heals thee.’ Then heal her now. The Word is true, ‘I am the Lord, I change not.’ Unchanging God, then prove Yourself the healer now. The Word is true. ‘These signs shall follow them that believe in My Name, they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover.’ And I believe and I lay hands in Jesus’ Name on her and claim this promise now. Your Word is true. ‘The prayer of faith shall save the sick. Trusting in You alone. I cry. Oh, save her now, for Jesus’ sake. Amen!”

Then, the maid lay in sleep so deep and sweet that the mother asked in a low whisper, “Is she dead?” “No,” I answered, in a whisper lower still. “Mary will live; the fever is gone. She is perfectly well and sleeping as an infant sleeps.” I was smoothing the long dark hair from her now peaceful brow, and feeling the steady pulsation of her heart and cool moist hands. I saw that Christ had heard, and that once more, as long ago in Peter’s house, “He touched her and the fever left her.” Turning to the nurse, I said, “Get me at once, please, a cup of cocoa and several slices of bread and butter.” Beside the sleeping maid we sat quietly and almost silently until the nurse returned, and then I bent over her and snapping my fingers called, “Mary!”

Instantly she woke, smiled and said, “Oh, sir, when did you come? I have slept so long;” then stretching her arms out to meet her mother’s embrace, she said, “Mother, I feel so well.” “And hungry, too?” I asked, pouring some of the cocoa in a saucer and offering it to her when cooled by my breath. “Yes, hungry too,” she answered with a little laugh, and drank and ate again, and yet again until all was gone. In a few minutes, she fell asleep, breathing easily and softly. Quietly thanking God. We left her bed and went to the next room where her brother and sister also lay sick of the same fever. With these two, we prayed and they were healed too. The following day all three were well and in a week or so they brought me a little letter and a gift of gold, two sleeve links with my monogram, which I wore for many years. As I went away from the home where Christ as the Healer had been victorious, I could not but have somewhat in my heart of the triumphant song that rang through Heaven, and yet I was not a little amazed at my own strange doings, and still more at my discovery that He is just the same today.

Excerpt from the Sermons of John Alexander Dowie Champions of Faith by Gordon Lindsay

"Do You Ever Think About Heaven"

Do you ever think about Heaven? The beauty, and how it will be to live in eternity with Jesus? No one knows all about Heaven. And I believe even if we were to see it in person it would be like attempting to define God; overwhelmingly magnificent in so many ways that it would be beyond description. However, some fascinating information about Heaven is in the Bible. So, with the Holy Spirit's prompting, I began to search the scriptures. What I found was a captivating spiritual glimpse of Heaven that I would like to share with you. Mansions I genuinely believe God has provided a home for us in Heaven “In my Father's house are many mansions: if it were not so, I would have told you. I go to prepare a place for you,” (John 14:2). There were "many mansions" in Heaven when Jesus made this statement, and He promised to create more. I believe there will be a place prepared for every child of God. Giving up this body will be painful only so far as it pertains to our earthly life, and even that is not as fearful as is typically portrayed, at least not for Christians. The answer is to have absolute belief in God. Having full confidence in His Word brings freedom, and a new dimension to life, and allows us to look forward to whatever He has for us on this earth and for the rest of eternity. The Beauty of Heaven The earth is beautiful with flowers of every color, and symmetry beyond imagination; beautiful fishes in the sea, and the mountains, valleys, rivers, a fantastic variety of animals, birds, seasons of the year, and yes, people, and they are all beautiful. Sunrises and sunsets, so many things we take for granted. But the beauty of the earth cannot compare with the magnificence of Heaven. When we think of Heaven, gates of pearl often come to mind. Pearls can consist of every color. The streets in Heaven are gold, and there is a crystal river flowing from the Throne of God. Biblical descriptions and experiences of those who have visited or received visions of Heaven report a scene of unimaginable beauty. Colors conveying incredible spiritual sensations, and music of another dimension. Heaven will not be a strange experience, but more natural than life on earth; because our citizenship is in Heaven. This earth is not our home. Our home is in Heaven with our Father and our brothers and sisters, with whom we will spend eternity. "For our citizenship is in heaven, from which we also eagerly wait for the Savior, the Lord Jesus Christ," (Phil 3:20. NKJV). The Father and Son will be there, and our family members and friends who have passed on. There will be Bible people and prophets and Apostles of the Old and New Testament, angels, and other heavenly beings gathered around the Throne of God, (another beauty beyond description). How Will it be to Live in Heaven? I see death as a door we pass through and on the other side a beautiful new way of life beyond comprehension. I believe when we begin to experience the glory of God, we will surely say, "O death, where is thy sting? O grave, where is thy victory?" (1 Cor 15:55). I believe we will have a real lifestyle in Heaven, a home, and that we will know one another: "For now we see in a mirror, dimly, but then face to face. Now I know in part, but then I shall know just as I also am known," (1 Cor 13:12, NKJV). There will be no sickness, heartache, pain, or tears because: "He will wipe away every tear from their eyes, and death shall be no more, neither shall there be mourning, nor crying, nor pain anymore, for the former things have passed away,” (Rev 21:4). Although no one can say with certainty how we will spend our time or what our responsibilities will be, we know that both Jesus and God work, so I believe we will have exciting work: But Jesus answered them, “My Father has been working until now, and I have been working,” (John 5:17). I am sure we will not be sitting on clouds with our feet dangling. I believe we will be busy, and that we will worship God alongside the angels. "And all the angels were standing around the throne and the elders and the four living creatures, and they fell on their faces before the throne and worshiped God," (Rev 7:11-12). There are many things the Bible does not tell us about Heaven. But I am convinced that our lifestyle will be like the other Gifts of God, far beyond anything we can ask or think, and that the parts we have not been told will be the best of all. New Heaven and New Earth "For here we have no lasting city, but we are seeking the city which is to come," (Heb13:14). At some point, there will be a new heaven and a new earth. We will have much to do, and I believe it will be enjoyable and that we will remain young and energetic forever. “In keeping with his promise we are looking forward to a new heaven and a new earth, where righteousness dwells,” (2 Pet 3:13). “The wolf will live with the lamb, the leopard will lie down with the goat, the calf and the lion and the yearling together; and a little child will lead them.” (Isa 11:6). The Apostle Paul's Heavenly Visit The Apostle Paul, speaking of himself in 2 Cor 12, said: "And I know such a man—whether in the body or out of the body I do not know, God knows— how he was caught up into Paradise and heard inexpressible words, which it is not lawful for a man to utter." "And lest I should be exalted above measure by the abundance of the revelations, a thorn in the flesh was given to me, a messenger of Satan to buffet me, lest I be exalted above measure," (2 Cor 12: 3-4, 7) Later, the Apostle Paul said that he was torn between leaving and staying; and that his only desire for remaining on earth was to tell others about the good news/Gospel, so they could also be with the Lord. "But I am hard-pressed between the two. I have the desire to leave [this world] and be with Christ, for that is far, far better; yet to remain in my body is more necessary and essential for your sake, (Phil 1: 23-24, AMP). Thoughts of Heaven should persuade those who hope for eternal life to follow God’s plan of salvation, and to do everything possible to bring their loved ones and others with them to a Heavenly Home prepared just for them. Jesus is With Us All the Way It is impossible to understand eternity. Even a thousand times ten thousand years will hardly be a mark in eternity. God considered it so valuable that He sent His only begotten Son to give His life so that anyone who was born-again would spend eternity with Him in Heaven. Like John Bunyan's "Pilgrim's Progress," the Christian journey to Heaven, except for the Holy Spirit, would be extremely challenging. However, we are not without the Holy Spirit, and Jesus promises to be with us all the way. “Teaching them to observe all things that I have commanded you; and lo, I am with you always, even to the end of the age.” Amen. (Matt 28:20). The sorrows, hardships, disappointments, and pain suffered on earth will be of little importance when we receive the first glimpse of our heavenly home. I often visualize my time of transition into Heaven as an experience so beautiful, fantastic and life-changing that it is difficult to think or concentrate on the troubles that plague humanity. I see my life as a journey, or time of preparation for a big event, the greatest adventure of my life. Although Jesus told us it would be a difficult journey, He also said we should continue and that someday we would hear these beautiful words: “Well done, good and faithful servant! You have been faithful with a few things; I will put you in charge of many things. Come and share your master's happiness!” (Matt 25:21, NLT). Samuel Mills