Others like in the beginning Features >>

About the Book

"In The Beginning" by Alister E. Mcgrath explores the intersection of science and religion, delving into the ongoing debate over the origins of the universe and the compatibility of faith and reason. Mcgrath discusses the relationship between science and theology, offering insights into how these two disciplines can coexist and complement each other. Through his exploration of these complex and controversial topics, Mcgrath encourages readers to consider the importance of both faith and reason in understanding the mysteries of life and the universe.

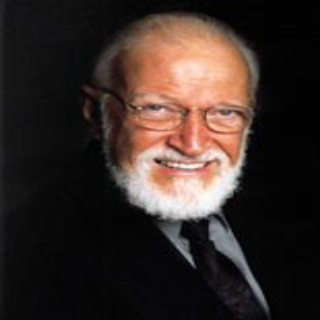

Calvin Miller

Calvin Miller was a pastor, professor and storyteller, best known for The Singer Trilogy, a mythic retelling of the New Testament story in the spirit of C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien. Miller passed away on the afternoon of August 19, 2012, due to complications after heart surgery. He was 75.

A prolific artist and a writer's writer, Miller garnered respect and praise throughout his career from peers like Luci Shaw, Max Lucado and Philip Yancey. He was the author of more than forty books of popular theology and Christian inspiration including such recent books as Letters to Heaven, The Path of Celtic Prayer, Letters to a Young Pastor and his memoir Life Is Mostly Edges.

In addition to his twenty years of pastoral service at Westside Church in Omaha, Nebraska, Miller was also a great mentor to many students and leaders through his preaching and pastoral ministry classes at Beeson Divinity School. Calvin Miller, never one to multiply words, used just four to describe his rule of life: "Time is a gift."

RESCUE FROM THE SLUSH PILE

In October 1973 one important book was rescued from the slush pile (the stack of unsolicited manuscripts every publisher receives) by assistant editor Don Smith. He read a manuscript by a little-known Baptist pastor in Nebraska that was a poetic retelling of the life of Jesus—portraying him as a Troubadour. Both he and Linda Doll excitedly encouraged Jim Sire to take this imaginative manuscript seriously. In February 1974 Sire wrote the author, Calvin Miller, that IVP wanted to publish his book The Singer.

Months before, Miller had been waking up nights, stirred to write this tale, perhaps unconsciously inspired by the recent Broadway hits Jesus Christ Superstar and Godspell. Later Miller wrote:

When the manuscript was done, I sent it to Jim Sire at InterVarsity Press. “It’s good,” he said, “but we want to think about it a couple of weeks before we give you an answer.” So I waited until finally the letter came. They were going to do it. Jim Sire had done his Ph.D. on John Milton, and the fact that he liked it was joy immeasurable to me. “But,” he cautioned, “we’re going to print five thousand of these. They may not do well—in fact we may end up with four thousand of them on skids in our basement for the next ten years. Still, it’s a good book and deserves to be in print.”

Far more than a thousand copies sold. Actually, over three hundred times that amount sold in its first decade. It became “the most successful evangelical publication in this genre.” The Singer was followed in two years by The Song (paralleling the story of the early church in Acts) and two years after that by The Finale (inspired by the book of Revelation). Publication of The Singer changed Miller’s life. Even though he stayed in the pastorate for many years, it set him on a course of writing and speaking that he could not have imagined.

Calvin Miller was a pastor, professor and storyteller, best known for The Singer Trilogy, a mythic retelling of the New Testament story in the spirit of C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien. Miller passed away on the afternoon of August 19, 2012, due to complications after heart surgery. He was 75.

A prolific artist and a writer's writer, Miller garnered respect and praise throughout his career from peers like Luci Shaw, Max Lucado and Philip Yancey. He was the author of more than forty books of popular theology and Christian inspiration including such recent books as Letters to Heaven, The Path of Celtic Prayer, Letters to a Young Pastor and his memoir Life Is Mostly Edges.

In addition to his twenty years of pastoral service at Westside Church in Omaha, Nebraska, Miller was also a great mentor to many students and leaders through his preaching and pastoral ministry classes at Beeson Divinity School. Calvin Miller, never one to multiply words, used just four to describe his rule of life: "Time is a gift."

RESCUE FROM THE SLUSH PILE

In October 1973 one important book was rescued from the slush pile (the stack of unsolicited manuscripts every publisher receives) by assistant editor Don Smith. He read a manuscript by a little-known Baptist pastor in Nebraska that was a poetic retelling of the life of Jesus—portraying him as a Troubadour. Both he and Linda Doll excitedly encouraged Jim Sire to take this imaginative manuscript seriously. In February 1974 Sire wrote the author, Calvin Miller, that IVP wanted to publish his book The Singer.

Months before, Miller had been waking up nights, stirred to write this tale, perhaps unconsciously inspired by the recent Broadway hits Jesus Christ Superstar and Godspell. Later Miller wrote:

When the manuscript was done, I sent it to Jim Sire at InterVarsity Press. “It’s good,” he said, “but we want to think about it a couple of weeks before we give you an answer.” So I waited until finally the letter came. They were going to do it. Jim Sire had done his Ph.D. on John Milton, and the fact that he liked it was joy immeasurable to me. “But,” he cautioned, “we’re going to print five thousand of these. They may not do well—in fact we may end up with four thousand of them on skids in our basement for the next ten years. Still, it’s a good book and deserves to be in print.”

Far more than a thousand copies sold. Actually, over three hundred times that amount sold in its first decade. It became “the most successful evangelical publication in this genre.” The Singer was followed in two years by The Song (paralleling the story of the early church in Acts) and two years after that by The Finale (inspired by the book of Revelation). Publication of The Singer changed Miller’s life. Even though he stayed in the pastorate for many years, it set him on a course of writing and speaking that he could not have imagined.

three classes of men

There is an obvious difference in the character and quality of the daily life of Christians. This difference is acknowledged and defined in the New Testament. There is also a possible improvement in the character and quality of the daily life of many Christians. This improvement is experienced by all such Christians who fulfill certain conditions. These conditions, too, form an important theme in the Word of God. The Apostle Paul, by the Spirit, has divided the whole human family into three groups: (1) The "natural man," who is unregenerate, or unchanged spiritually; (2) the "carnal man," who is a "babe in Christ," and walks "as a man"; and (3) the "spiritual" man. These groups are classified by the Apostle according to their ability to understand and receive a certain body of Truth, which is of things "revealed" unto us by the Spirit. Men are vitally different one from the other as regards the fact of the new birth and the life of power and blessing; but their classification is made evident by their attitude toward things revealed. In 1 Cor. 2:9 to 3:4 this threefold classification is stated. The passage opens as follows: "But as it is written, Eye hath not seen, nor ear heard, neither have entered into the heart of man, the things which God hath prepared for them that love him. But God hath revealed them unto us by his Spirit." A distinction is here drawn between those general subjects of human knowledge which are received through the eye-gate, the ear-gate, or the "heart" (the power to reason), and other subjects which are said to have been "revealed" unto us by His Spirit. There is no reference here to any revelation other than that which is already contained in the Scriptures of Truth, and this revelation is boundless, as the passage goes on to state: "For the Spirit [who reveals] searcheth all things, yea, the deep things of God." Men are classified according to their ability to understand and receive the "deep things of God." Into these "deep things of God" no unaided man can go. "For what man knoweth the things of a man, save the spirit of man which is in him? even so the things of God knoweth no man, but the Spirit of God" (knows them). An unaided man may enter freely into the things of his fellow man because of "the spirit of man which is in him." He cannot extend his sphere. He cannot know experimentally the things of the animal world below him, and certainly he cannot enter a higher sphere and know experimentally the things of God. Even though man, of himself, cannot know the things of God, the Spirit knows them, and a man may be so related to the Spirit that he too may know them. The passage continues: "Now we have received, not the spirit of the world, but the Spirit which is of God; that we may know the things [the "deep things of God," which eye hath not seen, etc.] that are freely given us of God." "We [that is, all saved, excluding none] have received the Spirit which is of God." Here is a great potentiality. Being so vitally related to the Spirit of God as to have Him abiding within, it is possible, because of that fact, to come to know "the things that are freely given to us of God." We could never know them of ourselves: the Spirit knows, He indwells, and He reveals. This divine revelation is transmitted to us in "words" which the Holy Spirit teacheth, as the Apostle goes on to state: "Which things also we speak, not in the words which man's wisdom teacheth, but which the Holy Spirit teacheth; comparing spiritual things with spiritual." God's Book is a Book of words and the very words which convey "man's wisdom" are used to convey things which "eye hath not seen, nor ear heard, neither have entered into the heart of man." Nevertheless unaided man cannot understand these "deep things of God," though couched in words most familiar to man, except as they are "revealed" by the Spirit. Just so, in coming to know these revealed things, progress is made only as one spiritual thing is compared with another spiritual thing. Spiritual things must be communicated by spiritual means. Apart from the Spirit there can be no spiritual understanding. The Natural Man "But the natural man receiveth not the things [the revealed or deep things] of the Spirit of God: for they are foolishness unto him: neither can he know them, because they are spiritually discerned." In this passage the natural man is not blamed for his inability. It is simply an accurate statement of the fact of his limitations. The passage also goes on to assign the exact cause of these limitations. We have just been told that revelation is by the Spirit. It therefore follows that the "natural man" is helpless to understand things revealed because he has not received "the Spirit which is of God." He has received only "the spirit of man which is in him." Though he may, with "man's wisdom," be able to read the words, he cannot receive their spiritual meaning. To him the revelation is "foolishness." He cannot "receive" it, or "know" it. The preceding verses of the context (1 Cor. 1:18,23) have defined a part of the divine revelation which is said to be "foolishness" to the "natural man": "For the preaching of the cross is to them that perish foolishness; but unto us which are saved it is the power of God." "But we preach Christ crucified, unto the Jews a stumbling block, and unto the Greeks [Gentiles] foolishness," Much more than the mere historical fact of the death of Christ is here meant. It is the divine unfolding of redemption through grace and includes all the eternal relationships that are made possible thereby. The moral principles and many of the religious teachings of the Bible are within the range of the capacity of the "natural man." From these sources he may eloquently preach; yea, and most seriously, not even knowing that "the deep things of God" exist. Satan, in his counterfeit systems of truth, is said to have "deep things" to reveal (Rev. 2:24) and "doctrines of devils" (1 Tim. 4:1-2) which things, on the other hand, are as certainly not received by the true child of God; for it is said, "And a stranger will they not follow, but will flee from him: for they know not the voice of strangers" (John 10:5). Yet the "deep things" of Satan are strangely adapted to the blinded, "natural man" and are, therefore, received by him. Every modern cult is evidence establishing the truthfulness of this statement. The unsaved man, though educated with all of "man's wisdom," and though religious and attentive, is blind to the gospel (2 Cor. 4:3-4) and if called upon to formulate a doctrinal statement, will naturally formulate a "new theology" which is so "re-stated" as to omit the real meaning of the cross with its unfolding of the "deep things of God." The cross, as a substitutionary sacrifice for sin, is "foolishness" unto him. His very limitations as a "natural man" demand that this shall be so. Human wisdom cannot help him, for "the world by wisdom knew not God." On the other hand, the boundless "deep things of God" are to be "freely" given to the one who has received "the Spirit which is of God." The true child of God may, therefore, be taught the divine revelation, having received the Spirit. A trained mind, it may be added, will greatly assist; but apart from the presence of the indwelling Teacher, a trained mind avails nothing in coming to know the spiritual meaning of the revealed things of God. Measureless evil has arisen through the supposition that because a man is well advanced in the "wisdom of this world," his opinions are of value in spiritual matters. The "natural man," with all his learning and sincerity, will find nothing but "foolishness" in the things which are revealed by the Spirit. The knowledge of science cannot be substituted for the indwelling of, and right relation to, the Holy Spirit of God. Apart from the Spirit there can be no regeneration, and the "deep things of God" are unknowable. When an unregenerate teacher openly rejects the vital saving truths of God's Word, those truths will usually be discredited and discarded by the pupil. This is the colossal blunder of many students in universities and colleges today. It is too generally assumed that the teacher or preacher who is an authority in some branch or branches of human knowledge is, by virtue of that knowledge, equally capable of discernment in spiritual things. It is not so. An unregenerate person (and who is more assuredly unregenerate than the one who denies the foundation and reality of the new birth?) will always be incapable of receiving and knowing the simplest truths of revelation. God is not a reality to the natural man. "God is not in all his thoughts." The unsaved man is therefore distressed and burdened to dispose of the supernatural. A baseless theory of evolution is his best answer to the problem of the origin of the universe. To the regenerate man, God is real and there is satisfaction and rest in the confidence that God is Creator and Lord of all. The ability to receive and know the things of God is not attained through the schools, for many who are unlearned possess it while many who are learned do not possess it. It is an ability which is born of the indwelling Spirit. For this reason the Spirit has been given to those who are saved that they might know the things which are freely given to them of God. Yet among Christians there are some who are under limitations because of their carnality. They are unable to receive "meat" because of carnality, rather than ignorance. There are no divine classifications among the unsaved, for they are all said to be "natural" men. There are, however, two classifications of the saved, and in the text under consideration, the "spiritual" man is named before the "carnal" man and is thus placed in direct contrast with the unsaved. This is fitting because the "spiritual" man is the divine ideal. "HE THAT IS SPIRITUAL" (1 Cor. 2:15) is the normal, if not the usual, Christian. But there is a "carnal" man and he must be considered. The Carnal Man The Apostle proceeds in chapter 3:1-4 with the description of the "carnal" man: "And I, brethren, could not speak unto you as unto spiritual, but as unto carnal, even as unto babes in Christ. I have fed you with milk, and not with meat: for hitherto ye were not able to bear it, neither yet now are ye able. For ye are yet carnal: for whereas there is among you envying, and strife, and divisions, are ye not carnal, and walk as men? For while one saith, I am of Paul; and another, I am of Apollos; are ye not carnal?" Some Christians, thus, are said to be "carnal" because they can receive only the milk of the Word, in contrast to the strong meat; they yield to envy, strife and divisions, and are walking as men, while the true child of God is expected to "walk in the Spirit" (Gal. 5:16), to "walk in love" (Eph. 5:2), and to "keep the unity of the Spirit" (Eph. 4:3). Though saved, the carnal Christians are walking "according to the course of this world." They are "carnal" because the flesh is dominating them (See Rom. 7:14). A different description is found in Rom. 8:5-7. There the one referred to is "in the flesh," and so is unsaved; while a "carnal" Christian is not "in the flesh," but he has the flesh in him. "But ye are not in the flesh, but in the Spirit if so be that the Spirit of God dwell in you. Now if any man have not the Spirit of Christ, he is none of his." The "carnal" man, or "babe in Christ," is not "able to bear" the deep things of God. He is only a babe; but even that, it is important to note, is a height of position and reality which can never be compared with the utter incapacity of the "natural man." The "carnal" man, being so little occupied with true spiritual meat, yields to envy and strife which lead to divisions among the very believers. No reference is made here to the superficial fact of outward divisions or various organizations. It is a reference to envy and strife which were working to sunder the priceless fellowship and love of the saints. Different organizations may often tend to class distinctions among the believers, but it is not necessarily so. The sin which is here pointed out is that of the believer who follows human leaders. This sin would not be cured were all the religious organizations instantly swept from the earth, or merged into one. There were present the "Paulites," the "Cephasites," the "Apollosites" and the "Christites" (cf. 1:12). These were not as yet rival organizations, but divisions within the Corinthian church that grew out of envy and strife. History shows that such divisions end in rival organizations. The fact of division was but the outward expression of the deeper sin of loveless, carnal lives. For a Christian to glory in sectarianism is "baby talk" at best, and reveals the more serious lack of true Christian love which should flow out to all the saints. Divisions will fade away and their offense will cease when the believers "have love one for the other." But the "carnal" Christian is also characterized by a "walk" that is on the same plane as that of the "natural" man. "Are ye not carnal, and walk as men (cf. 2 Cor. 10:2-5). The objectives and affections are centered in the same unspiritual sphere as that of the "natural" man. In contrast to such a fleshly walk, we read: "This I say then, Walk in the Spirit, and ye shall not fulfill the lust of the flesh." This is spirituality. The Spiritual Man The second classification of believers in this passage is of the spiritual man. He, too, is proven to be all that he is said to be by one test of his ability to receive and know the divine revelation. "He that is spiritual discerneth all things." The progressive order of this whole context is evident: First, the divine revelation is now given. It is concerning things which, "eye hath not seen, nor ear heard, neither have entered into the heart of man." It is revealed by the Spirit (1 Cor. 2:9-10). Second, the revelation is of the "deep things of God," which no man can know. However the Spirit knows them (1 Cor. 2:10). Third, believers have received the Spirit who knows, in order that they too may know the deep things of God (1 Cor. 2:12). Fourth, the divine wisdom is hidden in the very words of God's Book; but the spiritual content of these words is understood only as one is able to compare spiritual things with spiritual (1 Cor. 2:13). Fifth, the "natural man" cannot receive the things of the Spirit of God, for they are foolishness unto him, neither can he know them, because they are only by the Spirit discerned. He has not received the Spirit which is of God (1 Cor. 2:14). Sixth, a carnal Christian is born again and possesses the indwelling Spirit; but his carnality hinders the full ministry of the Spirit (1 Cor. 3:1-4). Seventh, "HE THAT IS SPIRITUAL" discerneth all things. There is no limitation upon him in the realm of the things of God. He can "freely" receive the divine revelation and he glories in it. He, too, may enter, as any other man, into the subjects which are common to human knowledge. He discerneth all things; yet he is discerned, or understood by no man. How could it be otherwise since he has "the mind of Christ?" There are two great spiritual changes which are possible to human experience—the change from the "natural" man to the saved man, and the change from the "carnal" man to the " spiritual" man. The former is divinely accomplished when there is a real faith in Christ; the latter is accomplished when there is a real adjustment to the Spirit. Experimentally the one who is saved through faith in Christ, may at the same time wholly yield to God and enter at once a life of true surrender. Doubtless this is often the case. It was thus in the experience of Saul of Tarsus (Acts 9:4-6). Having recognized Jesus as his Lord and Saviour, he also said, "Lord, what wilt thou have me to do?" There is no evidence that he ever turned from this attitude of yieldedness to Christ. However, it must be remembered that many Christians are carnal. To these the word of God gives clear directions as to the steps to be taken that they may become spiritual. There is then a possible change from the carnal to the spiritual state. The "spiritual" man is the divine ideal in life and ministry, in power with God and man, in unbroken fellowship and blessing. To discover these realities and the revealed conditions upon which all may be realized is the purpose of the following pages. From He That Is Spiritual by Lewis Sperry Chafer. New edition, rev. and enl. Philadelphia: Sunday School Times Company, ©1918.

.mobi-160.webp)