Others like business secrets from the bible Features >>

Secrets Of The Richest Man Who Ever Lived

Secrets Of The Richest Man Who Ever Lived

The Money Answer Book

Wealth Creation

Money With A Mission

Wealth Building 101

-160.webp)

Wealth Of Wisdom (The Top 50 Questions Wealthy Families Ask)

The Wealth And Poverty Of Nations - Why Some Are So Rich And Some So Poor

Five Wealth Secrets

About the Book

"Business Secrets from the Bible" by Daniel Lapin explores timeless principles and wisdom found in the Bible that can be applied to achieve success in business. Lapin discusses concepts such as serving others, hard work, integrity, and financial responsibility, providing practical advice for individuals looking to excel in their professional lives. Overall, the book offers a unique perspective on how to approach business based on biblical teachings.

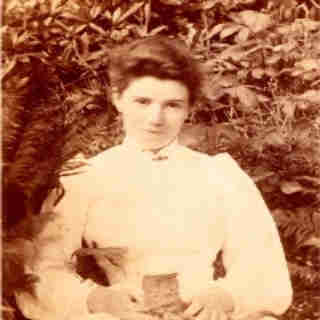

Amy Carmichael

Born in Belfast Ireland, to a devout family of Scottish ancestry, Carmichael was educated at home and in England, where she lived with the familt of Robert Wilson after her father’s death. While never officially adopted, she used the hyphenated name Wilson-Carmichael as late as 1912. Her missionary call came through contacts with the Keswick movement. In 1892 she volunteered to the China Inland Mission but was refused on health grounds. However, in 1893 she sailed for Japan as the first Keswick missionary to join the Church Missionary Society (CMS) work led by Barclay Buxton. After less than two years in Japan and Ceylon, she was back in England before the end of 1894. The next year she volunteered to the Church of England Zenana Missionary Society, and in November 1895 she arrived in South India, never to leave. While still learning the difficult Tamil language, she commenced itinerant evangelism with a band of Indian Christian women, guided by the CMS missionary Thomas Walker. She soon found herself responsible for Indian women converts, and in 1901, she, the Walkers, and their Indian colleagues settled in Dohnavur. During her village itinerations, she had become increasingly aware of the fact that many Indian children were dedicated to the gods by their parents or guardians, became temple children, and lived in moral and spiritual danger. It became her mission to rescue and raise these children, and so the Dohnavur Fellowship came into being (registered 1927). Known at Dohnavur as Amma (Mother), Carmichael was the leader, and the work became well known through her writing. Workers volunteered and financial support was received, though money was never solicited. In 1931 she had a serious fall, and this, with arthritis, kept her an invalid for the rest of her life. She continued to write, and identified leaders, missionary and Indian, to take her place. The Dohnavur Fellowship still continues today.

Jocelyn Murray, “Carmichael, Amy Beatrice,” in Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions, ed. Gerald H. Anderson (New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 1998), 116.

This article is reprinted from Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions, Macmillan Reference USA, copyright © 1998 Gerald H. Anderson, by permission of Macmillan Reference USA, New York, NY. All rights reserved.

“Ammai” of orphans and holiness author

Amy Carmichael was born in Ireland in 1867, the oldest of seven children. As a teen, she attended a Wesleyan Methodist girls boarding school, until her father died when she was 18. Carmichael twice attended Keswick Conventions and experienced a holiness conversion which led her to work among the poor in Belfast. Through the Keswick Conventions, Carmichael met Robert Wilson. He developed a close relationship with the young woman, and invited her to live with his family. Carmichael soon felt a call to mission work and applied to the China Inland Mission as Amy Carmichael-Wilson. Although she did not go to China due to health reasons, Carmichael did go to Japan for a brief period of time. There she dressed in kimonos and began to learn Japanese. Her letters home from Japan became the basis for her first book, From Sunrise Land. Carmichael left Japan due to health reasons, eventually returning to England. She soon accepted a position with the Church of England’s Zenana Missionary Society, serving in India. From 1895 to 1925, her work with orphans in Tinnevelly (now Tirunelveli) was supported by the Church of England. After that time, Carmichael continued her work in the faith mission style, establishing an orphanage in Dohnavur. The orphanage first cared for girls who had been temple girls, who would eventually become temple prostitutes. Later the orphanage accepted boys as well.

Carmichael never returned to England after arriving in India. She wrote prolifically, publishing nearly 40 books. In her personal devotions, she relied on scripture and poetry. She wrote many of her own poems and songs. Carmichael had a bad fall in 1931, which restricted her movement. She stayed in her room, writing and studying. She often quoted Julian of Norwich when she wrote of suffering and patience. Many of Carmichael’s books have stories of Dohnavur children, interspersed with scripture, verses, and photographs of the children or nature. Carmichael never directly asked for funding, but the mission continued to be supported through donations. In 1951 Carmichael died at Dohnavur. Her headstone is inscribed “Ammai”, revered mother, which the children of Dohnavur called Carmichael.

Carmichael’s lengthy ministry at Dohnavur was sustained through her strong reliance upon scripture and prayer. Her early dedication to holiness practices and her roots in the Keswick tradition helped to guide her strong will and determination in her mission to the children of southern India.

by Rev. Lisa Beth White

Born in Belfast Ireland, to a devout family of Scottish ancestry, Carmichael was educated at home and in England, where she lived with the familt of Robert Wilson after her father’s death. While never officially adopted, she used the hyphenated name Wilson-Carmichael as late as 1912. Her missionary call came through contacts with the Keswick movement. In 1892 she volunteered to the China Inland Mission but was refused on health grounds. However, in 1893 she sailed for Japan as the first Keswick missionary to join the Church Missionary Society (CMS) work led by Barclay Buxton. After less than two years in Japan and Ceylon, she was back in England before the end of 1894. The next year she volunteered to the Church of England Zenana Missionary Society, and in November 1895 she arrived in South India, never to leave. While still learning the difficult Tamil language, she commenced itinerant evangelism with a band of Indian Christian women, guided by the CMS missionary Thomas Walker. She soon found herself responsible for Indian women converts, and in 1901, she, the Walkers, and their Indian colleagues settled in Dohnavur. During her village itinerations, she had become increasingly aware of the fact that many Indian children were dedicated to the gods by their parents or guardians, became temple children, and lived in moral and spiritual danger. It became her mission to rescue and raise these children, and so the Dohnavur Fellowship came into being (registered 1927). Known at Dohnavur as Amma (Mother), Carmichael was the leader, and the work became well known through her writing. Workers volunteered and financial support was received, though money was never solicited. In 1931 she had a serious fall, and this, with arthritis, kept her an invalid for the rest of her life. She continued to write, and identified leaders, missionary and Indian, to take her place. The Dohnavur Fellowship still continues today.

Jocelyn Murray, “Carmichael, Amy Beatrice,” in Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions, ed. Gerald H. Anderson (New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 1998), 116.

This article is reprinted from Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions, Macmillan Reference USA, copyright © 1998 Gerald H. Anderson, by permission of Macmillan Reference USA, New York, NY. All rights reserved.

“Ammai” of orphans and holiness author

Amy Carmichael was born in Ireland in 1867, the oldest of seven children. As a teen, she attended a Wesleyan Methodist girls boarding school, until her father died when she was 18. Carmichael twice attended Keswick Conventions and experienced a holiness conversion which led her to work among the poor in Belfast. Through the Keswick Conventions, Carmichael met Robert Wilson. He developed a close relationship with the young woman, and invited her to live with his family. Carmichael soon felt a call to mission work and applied to the China Inland Mission as Amy Carmichael-Wilson. Although she did not go to China due to health reasons, Carmichael did go to Japan for a brief period of time. There she dressed in kimonos and began to learn Japanese. Her letters home from Japan became the basis for her first book, From Sunrise Land. Carmichael left Japan due to health reasons, eventually returning to England. She soon accepted a position with the Church of England’s Zenana Missionary Society, serving in India. From 1895 to 1925, her work with orphans in Tinnevelly (now Tirunelveli) was supported by the Church of England. After that time, Carmichael continued her work in the faith mission style, establishing an orphanage in Dohnavur. The orphanage first cared for girls who had been temple girls, who would eventually become temple prostitutes. Later the orphanage accepted boys as well.

Carmichael never returned to England after arriving in India. She wrote prolifically, publishing nearly 40 books. In her personal devotions, she relied on scripture and poetry. She wrote many of her own poems and songs. Carmichael had a bad fall in 1931, which restricted her movement. She stayed in her room, writing and studying. She often quoted Julian of Norwich when she wrote of suffering and patience. Many of Carmichael’s books have stories of Dohnavur children, interspersed with scripture, verses, and photographs of the children or nature. Carmichael never directly asked for funding, but the mission continued to be supported through donations. In 1951 Carmichael died at Dohnavur. Her headstone is inscribed “Ammai”, revered mother, which the children of Dohnavur called Carmichael.

Carmichael’s lengthy ministry at Dohnavur was sustained through her strong reliance upon scripture and prayer. Her early dedication to holiness practices and her roots in the Keswick tradition helped to guide her strong will and determination in her mission to the children of southern India.

by Rev. Lisa Beth White

learning the lyrics of god

A preacher once told me, “Although I often read a psalm to people in the hospital, I would never consider preaching from a psalm because I do not know what to do with it.” Not knowing “what to do” with the poetry of the Bible has made biblical poetry a closed book to many Christians. Happily, it is a problem with a ready solution. We can learn “what to do” with the poetry of the Bible. The purpose of this article is to equip pastors, Bible teachers, and laypeople to handle the poetry of the Bible with zest and confidence. To achieve this purpose, I have divided my material into three topics, as follows: three common fallacies about poetry that need to be refuted the seven most important things you need to know about the poetry of the Bible three tips for handling the poetry of the Bible with confidence Three Fallacies About Poetry The first fallacy that we need to lay to rest is that poetry is beyond the reach of people today. In the past, say many people in the pew, poetry was a normal part of life, but that is no longer true. I increasingly hear of people pressuring Sunday school teachers to leave the poetry of the Bible untouched, and preachers have been influenced by the same trend of the time. There is no chronological factor whatsoever in the accessibility of poetry. People in Bible times were not in a privileged position in regard to poetry. The situation might actually be the reverse. Our own world is image-oriented, matching the way in which poetry relies on imagery (words naming concrete objects and actions). Additionally, people in an age of texting are accustomed to brief modes of communication, and poetry is likewise a compressed form of discourse. Equally fallacious is the claim that poetry is an unnatural form of discourse. People who make the claim incorrectly believe that prose is the natural form of communication, and poetry an aberration. All of us speak poetry part of the time. For example, we sing hymns, which begin as poems and become hymns only when music is added to them (after which they do not cease to be poems). We speak of the sun rising and setting, of game changers and cliff hangers, of killing time and juggling our schedule. All of these are poetic metaphors. Why do we use them? Because we correctly sense that poetic speech often conveys truth more effectively than literal prose. A third misconception is that poetry is unrelated to real life. This is doubly false. At the verbal level of the actual language used, poetry stays close to the everyday experiences of life. Biblical poets keep us rooted in a world of water and sheep and light and pathways. Additionally, at the level of content, poems have exactly the same subject as all other literature, namely, universal human experience. Both of these points — that poetic language and the content of poems put us in touch with everyday experience — were encapsulated in the title of a book on poetry: Poetry and the Common Life . 1 Seven Things You Need to Know About Poetry Fiction writer Flannery O’Connor famously said that “the writer should never be ashamed of staring.” She meant that literary authors need to be close observers of life. Teachers of literature often adapt O’Connor’s statement and apply it to readers: readers, too, should never be ashamed of staring at a text. But we should not say this glibly. Merely staring at a poem in the Bible will yield meager results. We need to know what to look for , which is to say that we need to know how poetry works. We can begin with seven things readers need to know about poetry. 1. We know that God expects us to understand and enjoy poetry. This is not a controversial claim. We know that God wants us to have poetry as a component of our spiritual lives because at least a third of the Bible comes to us in the form of poetry. Poetry is present throughout the Bible. For starters, we can think of books that are wholly or largely poetic in format: Psalms, Proverbs, Song of Solomon, and Job. But those are only the obvious places where we find poetry in the Bible. The books of Ecclesiastes and Revelation, though printed mainly as prose, are actually poetic in their technique. Jesus’s discourses are heavily poetic in their language, and it is no stretch to say that Jesus is one of the world’s most famous poets. Beyond these saturated poetic parts of the Bible, we find metaphors and other figures of speech on nearly every page of the Bible. The New Testament epistles feature passages like the following as a staple: “At one time you were darkness, but now you are light in the Lord. Walk as children of light” (Ephesians 5:8). We can draw three conclusions from the fact that God gave us a poetic Bible. The first is that it gives us and our charges an incentive to embrace and master the poetry of the Bible. If God gave us poetry, he wants it to be present in our lives. Second, the heavy incidence of poetry in the Bible stands as a rebuke to people who disparage it and try to steer us away from it. God is not honored by lazy Bible readers who refuse to master the poetic parts of the Bible. Third, if poetry permeates the entire Bible, we need to be ready to recognize it wherever it appears, not just in the obviously poetic parts, and to deal with it as poetry. 2. Poetry requires a slow read. Poetry requires us to read it slowly and analytically. This stands in contrast to the trends of our time. To read slowly is the opposite of the speed reading that our culture encourages. Poetry also differs from genres such as expository prose and stories that carry their meaning largely on the surface. When I said earlier in this paragraph that poetry requires us to read it analytically, I did not mean meditatively , though that is a good way to read everything in the Bible. Meditation is the reflection and application in which we engage after we have assimilated a text. By analysis I mean that poetry embodies its meanings in images and figures of speech that require us to unpack them. After we have done that, we can proceed to meditate on what we have uncovered. 3. Poets speak a language all their own. In resisting the claim that poetry is an unnatural form of discourse, I am not saying that poetry is our normal way of speaking. Poetry is a specialized form of discourse. But so is prose. In ordinary conversation, we often do not speak in prose (complete sentences that follow the rules of grammar). Instead, we speak an associative form of communication consisting of single words and phrases, disjointed and incomplete sentence fragments, arranged by stream of consciousness instead of formal syntax and logical argument. The drift of what I am saying is that the entire Bible, prose as well as poetry, requires analysis and unpacking. Very little in the Bible resembles the conversation at the local coffee shop. To return to the announced point, poets speak in what can be called a poetic idiom. It consists of images and figures of speech. All that this means is that we need to educate ourselves into the expectations of poetic discourse, just as we need to educate ourselves into how stories and epistles work. At this point, poetry is no different from the rest of the Bible: dealing with it competently depends on allowing the expectations of the genre to govern our encounter with a text. 4. Poets think in images and figures of speech. Poetry is a way of thinking and feeling before it is a form of speech or writing. Poets write in a poetic idiom because during the process of composition that is how they experience life and record it. As a byproduct of this, we need to credit poets with possessing a skill of expression and perception of the world that most people lack. But this does not separate poets from us; it only means that poets are our representatives. They say what we, too, want said, only they say it better and in a distinctive way. If poets think in images, so must we as readers. 5. Poetry is a form of logic. Modern poet Stephen Spender wrote in his famous essay “The Making of a Poem” that “the terrifying challenge” facing a poet is the question “Can I think out the logic of images?” 2 If we think of poetry as a form of logic, a door is opened into seeing it as more like ordinary speech than we might otherwise think. Logic means making an accurate connection between two things. We can always ask, Why did the poet use this image for this subject matter? Similarly with the comparisons (metaphors and similes) that poets continually spring on us: How is A like B? What is the logic of calling God a shepherd (Psalm 23:1), and the godly person a tree planted by a stream of water (Psalm 1:3)? 6. Poetry is an invitation to discover meaning. Poetry does not carry all of its meaning on the surface. In fact, it is akin to a riddle in the sense that it requires us to discover the meanings that a poet has embedded in the poetic texture of a poem (the images and figures of speech). The poet simply puts a figure of speech before us, such as “the name of the Lord is a strong tower” (Proverbs 18:10), and expects us to figure out the meanings of the comparison. Instead of chafing under this obligation, we and our audiences should relish the opportunity to be active in discovering God’s truth. Unpacking the meanings embedded in poetry can be a pleasurable experience, and additionally it is good at activating a Bible study group in a process of joint discovery. 7. Poetry is concentrated. An additional trait of poetry has been implied above, namely, that poetry is the most compressed form of discourse. Individual images and comparisons rarely embody just one meaning. When a biblical poet compares the experience of trusting in God to living in his house (Psalm 91:1), the meanings are multiple. None of these traits puts poetry beyond the reach of anyone. The real obstacle to reading the poetry of the Bible is not its alleged difficulty. It is instead unwillingness to spend the time and mental thought required to unpack the meanings that poetry embodies. Three Principles of Poetry In any sphere of life, our methods of accomplishing a task need to be based on an understanding of the principles involved. Perhaps you have shared my experience of trying to screw a bottle top onto a bottle, only to discover eventually that it needed to be pushed on instead. What follows is a section of methodology, equivalent to the first class meeting on poetry in my Bible-as-literature courses. What I am about to say should be understood as constituting “first things” when dealing with the poetry of the Bible. What we need to do first is master the actual poetic texture of a poem (the words, images, and figures of speech). After all, this is what embodies the content. We need to avoid putting matters of secondary importance ahead of analysis of poetic texture. I remember how shocked I was when a biblical scholar said that the first thing he would talk about with biblical poetry is parallelism. That is totally unhelpful. Poetic meaning is embodied in the poetic texture; parallelism is only the verse form in which the content is packaged. It is not unimportant, but it is far down on the agenda of topics that need to be addressed as we deal with a poem. Another preliminary point that I need to make is the distinction between poetry and poem . Poetry is the language poets use, as I am about to discuss it. This language often goes by the name the poetic idiom . Poems are compositions constructed out of poetic language. Many specific genres fill out the repertoire of poems — praise psalm, for example, or oracle of judgment, or Christ hymn. In the space at my disposal, I will concentrate on the essentials of poetry . This is what gets shortchanged in conventional biblical scholarship and Bible study methods. I have divided my primer on poetic discourse into three principles. Poetic Principle 1: The Primacy of the Image An image is any word that names a concrete object or action. In Psalm 1:1, walking, standing, sitting, the way or path, and the seat are all images. I need immediately to note a complexity. In the Bible, “the straight image” is relatively rare. Most images in the Bible are part of a metaphor, simile, or symbol. The picture that Amos paints in his satiric portrait of the complacent wealthy of his society employs straight imagery. Thus, lying on beds of ivory (Amos 6:4) is an example of a straight image because it is not part of a metaphor or simile — the rich in Israel really were lying on beds of ivory. But analysis of a metaphor or simile needs to begin the same way we handle a straight image. In comparisons such as metaphors and similes (which I will shortly discuss), A is said to be like B. Every comparison of this type is an image first (level A), and the meanings we assign to this image at level A are then carried over to level B. This means that everything I am about to say about the primacy of the image in poetry applies to metaphors, similes, and symbols as well as straightforward images. Dealing with a poetic image starts at the literal level of identifying the exact nature of the image. This is usually but not always self-evident. In Psalm 121:6, the striking of the sun by day is obviously the threat of sun stroke and heat exhaustion, but the image in the next line of the striking of the moon by night requires research. Once we have the literal image correctly identified, we need to do three more things with it. First, an image requires us to determine its connotations, either universally or in the specific context of the poem where the image appears. Abiding in a shelter or house (Psalm 91:1) embodies connotations of safety, protection, provision, proximity to others living in the same house, and loving relationship. Second, images usually evoke feelings. Naming the feelings evoked by an image — determining its affective meanings — is an entirely legitimate and helpful form of commentary. Third, we need to explore the logic of an image. Logic involves making accurate connections between two things. To explore the logic of a poetic image means determining why the poet chose a particular image for the experience that is being presented. Before I move to my additional “first things” in regard to poetry, I need to take time out to say that I hope you are not impatient with my nuts-and-bolts approach to the poetry of the Bible. The reason poetry is not treated as poetry in our circles is that interpreters do not begin at the foundational level that I am delineating. I once surveyed what commentaries and study Bibles did with an image that appears more than half a dozen times in the Psalms — raising up a horn (e.g., Psalm 75:10; 89:17; 112:9; 148:14). None of my sources told me what the literal image is; all the attention was devoted to interpreting the conceptual meaning of the image. Poetry needs to be read and interpreted in terms of what it is, starting at the foundational level of its imagery. Poetic Principle 2: The Importance of Comparison or Analogy As far back as the oldest surviving piece of literary theory, Aristotle’s Poetics , the ability to see resemblances has been regarded as the most crucial test of a poet’s ability. Analogy in poetry takes three forms: metaphor: an implied comparison between two things that does not use the explicit formula like or as simile: an explicitly stated comparison that uses the formula like or as symbol: an image that embodies meanings beyond the thing named Some will be surprised to see symbol on my list, but a symbol operates on the same principle of analogy that the other two do. A symbol has its literal identity (level A) and then adds one or more other meanings to it (level B). What is the effect when a poet draws our attention to a correspondence between two things? It is ingenious: the poet uses one area of human experience to illuminate or shed light on another area. In Psalm 23, a shepherd’s acts of provision for his sheep during a typical day illuminate how God provides for human needs. Poetic analogy is a form of logical equation, as one thing is said to be equivalent to something else. Another helpful term is the word bifocal : in a metaphor, simile, and symbol, we are required to look at two things — the experience being presented and the image to which it is compared. What interpretive actions do poetic comparisons require us to perform? This is where the word metaphor is worth its weight in gold. The word is based on two Greek words meaning “to carry over.” That is exactly what we need to do. If “the tongue is a fire” (James 3:6), we first need to determine what the literal properties of fire are, and then we need to carry over those meanings to the subject of human words and speech. Poetry is concentrated, and it is a rare poetic analogy that has only one point of correspondence. Three things follow from what I have said. First, poetry is based on a principle of indirection. Poet Robert Frost said that poetry is a way of saying one thing while meaning another. The poet says that the name of the Lord is a strong tower (Proverbs 18:10); he means that God is a strong protector with whom we are safe. Second, metaphors, similes, and symbols are an invitation to discover meaning. The poets of the Bible state that A is like B, trusting us to complete the process of communication that they have begun. Third, merely labeling a figure of speech correctly is of very limited value. What matters is that we unpack the meanings embodied in a figure of speech. Poetic Principle 3: Poets’ Preference for the Nonliteral Let me first simply name additional figures of speech that occur so often in biblical poetry that we need to know what they are: apostrophe; synecdoche; metonymy; personification; allusion; paradox; merism. Definitions of these are available on the Internet; for a more analytic discussion of how they actually work, I recommend my book A Complete Handbook of Literary Forms in the Bible . 3 Most of these figures of speech are fictional and often fantastic rather than factual or literal. In apostrophe, for example, a poet addresses someone not literally present (“O kings” in Psalm 2:10), or something that is inanimate and therefore incapable of hearing and responding (“mountains and all hills” in Psalm 148:9), as though these were present and capable of hearing and responding. It is no wonder the world has coined the label poetic license . We need to handle the poetry of the Bible in the spirit in which it is offered to us, respecting the far-flung imagination of its poets. Embracing the Bible’s Poetry The foregoing has doubtless seemed like sitting in a college literature class. This is exactly what you need in order to read and teach and preach on biblical poetry with confidence. At the beginning of this article, I quoted a preacher who recalled the era of his life when he avoided preaching from the Psalms because he did not know “what to do” with a psalm. After he embraced a literary approach to the Bible along the lines of what I have said in this article, he no longer avoided preaching on biblical poetry. In this article, I have opened a door that can enable you to know what do with a biblical poem. I have one more challenge for you: if preachers and Bible study leaders would devote just two minutes in a sermon or Bible study session to teach or remind their audience of individual pieces of literary methodology, church members would quickly become adept at handling the Bible. A reminder of what a poetic image or analogy requires us to do, or that stories are made up of plot, setting, and character, would equip the person in the pew to deal with biblical texts in terms of what they really are. We have been guilty of a great abdication in this regard, but the remedy is straightforward. All it takes is resolve. M.L. Rosenthal, Poetry and the Common Life (New York: Persea Books, 1974). ↩ Stephen Spender, The Making of a Poem (New York: Norton, 1962), 54. ↩ Leland Ryken, A Complete Handbook of Literary Forms in the Bible (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2014). ↩