Others like by grace alone Features >>

About the Book

In "By Grace alone," Derek Prince explores the concept of grace as a gift from God that cannot be earned through works or good deeds. He delves into the significance of grace in the Christian faith, emphasizing its power to transform lives and bring believers closer to God. Prince highlights the importance of understanding and accepting God's grace in order to experience true freedom and fulfillment in Christ.

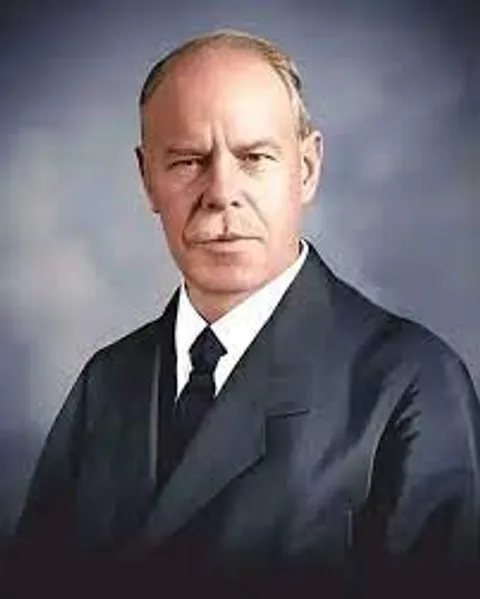

Smith Wigglesworth

Smith Wigglesworth was born in 1859 to a very poor family. His father did manual labor, for very little pay. Smith himself went to work at the age of six to help with the family income. At six he was pulling turnips and at seven he was working in a woolen mill twelve hours a day. His parents did not know God, but Smith hungered in his heart to know Him. Even as a youngster he would pray in the fields. His grandmother was the critical Christian in his life. She was a Wesleyan Methodist and would take Smith to meetings with her. At one of these meetings there was a song being sung about Jesus as the lamb and Smith came into the realization of God's love for him and his decision to believe Christ for his salvation was decided that day. He was immediately filled with the desire to evangelize and led his own mother to Christ.

Smith has various church experiences as he was growing up. He first went to an Episcopal church and then at thirteen a Wesleyan Methodist church. When he was sixteen he became involved in the Salvation Army. He felt deeply called to fast and pray for lost souls. He saw many people come to Christ. At seventeen a mentor shared with him about water baptism and he decided to be baptized. The Salvation Army was experiencing a tremendous level of the power of God in those days. He describes meetings where "many would be prostrated under the power of the Spirit, sometimes for as long as twenty-four hours at a time." They would pray and fast and cry out for the salvation of fifty or a hundred people for the week and they would see what they had prayed for.

At eighteen Smith left the factory and became a plumber. He moved to Liverpool when he was twenty and continued to work during the day and minister during his free time. He felt called to minister to young people and brought them to meetings. These were destitute and ragged children, whom he would often feed and care for. Hundreds were saved. Smith was often asked to speak in Salvation meetings and he would break down and weep under the power of God. Many would come to repentance in those meetings through this untrained man. At twenty-three he returned back Bradford and continued his work with the Salvation Army.

In Bradford Smith met Mary Jane Featherstone, known as Polly, the daughter of a temperance lecturer. She left home and went to Bradford to take a servants job. One night she was drawn to a Salvation Army meeting. She listened to the woman evangelist, Gipsy Tillie Smith, and gave her heart to Christ. Smith was in that meeting and saw her heart for God. Polly became an enthusiastic Salvationsist and was granted a commission by General Booth. They developed a friendship, but Polly went to Scotland to help with a new Salvationist work. She eventually moved back to Bradford and married Smith, who was very much in love with her.

The couple worked together to evangelize the lost. They opened a small church in a poor part of town. Polly would preach and Smith would make the altar calls. For a season, however, Smith became so busy with his plumbing work that his evangelistic fervor began to wane. Polly continued on, bringing Smith to conviction. One day while Smith was working in the town of Leeds he heard of a divine healing meeting. He shared with Polly about it. She needed healing and so they went to a meeting, and Polly was healed.

Smith struggled with the reality of healing, while being ill himself. He decided to give up the medicine that he was taking and trust God. He was healed. They had five children, a girl and four boys. One morning two of the boys were sick. The power of God came and they prayed for the boys and they were instantly healed. Smith struggled with the idea that God would use him to heal the sick in general. He would gather up a group of people and drive them to get prayer in Leeds. The leaders of the meeting were going to a convention and left Smith in charge. He was horrified. How could he lead a meeting about divine healing? He tried to pass it off to someone else but could not. Finally he led the meeting and several people were healed. That was it. From then on Smith began to pray for people for healing.

Smith had another leap to make. He had heard about the Pentecostals who were being baptized in the Holy Spirit. He went to meetings and was so hungry for God he created a disturbance and church members asked him to stop. He went to prayer and prayed for four days. Finally he was getting ready to head home and the vicar's wife prayed for him and he fell under the power of God and spoke in tongues. Everything changed after that. He would walk by people and they would come under the conviction of the Holy Spirit and be saved. He began to see miracles and healings and the glory of God would fall when he prayed and preached.

Smith had to respond to the many calls that came in and gave up his business for the ministry. Polly unexpectedly died in 1913, and this was a real blow to Smith. He prayed for her and commanded that death release her. She did arise but said "Smith - the Lord wants me." His heartbroken response was "If the Lord wants you, I will not hold you". She had been his light and joy for all the years of their marriage, and he grieved deeply over the loss. After his wife was buried he went to her grave, feeling like he wanted to die. When God told him to get up and go Smith told him only if you "give to me a double portion of the Spirit – my wife’s and my own – I would go and preach the Gospel. God was gracious to me and answered my request.” His daughter Alice and son-in-law James Salter began to travel with him to handle his affairs.

Smith would pray and the blind would see, and the deaf were healed, people came out of wheelchairs, and cancers were destroyed. One remarkable story is when He prayed for a woman in a hospital. While he and a friend were praying she died. He took her out of the bed stood her against the wall and said "in the name of Jesus I rebuke this death". Her whole body began to tremble. The he said "in the name of Jesus walk", and she walked. Everywhere he would go he would teach and then show the power of God. He began to receive requests from all over the world. He taught in Europe, Asia, New Zealand and many other areas. When the crowds became very large he began a "wholesale healing". He would have everyone who needed healing lay hands on themselves and then he would pray. Hundreds would be healed at one time.

Over Smith's ministry it was confirmed that 14 people were raised from the dead. Thousands were saved and healed and he impacted whole continents for Christ. Smith died on March 12, 1947 at the funeral of his dear friend Wilf Richardson. His ministry was based on four principles " First, read the Word of God. Second, consume the Word of God until it consumes you. Third believe the Word of God. Fourth, act on the Word."

Smith Wigglesworth was born in 1859 to a very poor family. His father did manual labor, for very little pay. Smith himself went to work at the age of six to help with the family income. At six he was pulling turnips and at seven he was working in a woolen mill twelve hours a day. His parents did not know God, but Smith hungered in his heart to know Him. Even as a youngster he would pray in the fields. His grandmother was the critical Christian in his life. She was a Wesleyan Methodist and would take Smith to meetings with her. At one of these meetings there was a song being sung about Jesus as the lamb and Smith came into the realization of God's love for him and his decision to believe Christ for his salvation was decided that day. He was immediately filled with the desire to evangelize and led his own mother to Christ.

Smith has various church experiences as he was growing up. He first went to an Episcopal church and then at thirteen a Wesleyan Methodist church. When he was sixteen he became involved in the Salvation Army. He felt deeply called to fast and pray for lost souls. He saw many people come to Christ. At seventeen a mentor shared with him about water baptism and he decided to be baptized. The Salvation Army was experiencing a tremendous level of the power of God in those days. He describes meetings where "many would be prostrated under the power of the Spirit, sometimes for as long as twenty-four hours at a time." They would pray and fast and cry out for the salvation of fifty or a hundred people for the week and they would see what they had prayed for.

At eighteen Smith left the factory and became a plumber. He moved to Liverpool when he was twenty and continued to work during the day and minister during his free time. He felt called to minister to young people and brought them to meetings. These were destitute and ragged children, whom he would often feed and care for. Hundreds were saved. Smith was often asked to speak in Salvation meetings and he would break down and weep under the power of God. Many would come to repentance in those meetings through this untrained man. At twenty-three he returned back Bradford and continued his work with the Salvation Army.

In Bradford Smith met Mary Jane Featherstone, known as Polly, the daughter of a temperance lecturer. She left home and went to Bradford to take a servants job. One night she was drawn to a Salvation Army meeting. She listened to the woman evangelist, Gipsy Tillie Smith, and gave her heart to Christ. Smith was in that meeting and saw her heart for God. Polly became an enthusiastic Salvationsist and was granted a commission by General Booth. They developed a friendship, but Polly went to Scotland to help with a new Salvationist work. She eventually moved back to Bradford and married Smith, who was very much in love with her.

The couple worked together to evangelize the lost. They opened a small church in a poor part of town. Polly would preach and Smith would make the altar calls. For a season, however, Smith became so busy with his plumbing work that his evangelistic fervor began to wane. Polly continued on, bringing Smith to conviction. One day while Smith was working in the town of Leeds he heard of a divine healing meeting. He shared with Polly about it. She needed healing and so they went to a meeting, and Polly was healed.

Smith struggled with the reality of healing, while being ill himself. He decided to give up the medicine that he was taking and trust God. He was healed. They had five children, a girl and four boys. One morning two of the boys were sick. The power of God came and they prayed for the boys and they were instantly healed. Smith struggled with the idea that God would use him to heal the sick in general. He would gather up a group of people and drive them to get prayer in Leeds. The leaders of the meeting were going to a convention and left Smith in charge. He was horrified. How could he lead a meeting about divine healing? He tried to pass it off to someone else but could not. Finally he led the meeting and several people were healed. That was it. From then on Smith began to pray for people for healing.

Smith had another leap to make. He had heard about the Pentecostals who were being baptized in the Holy Spirit. He went to meetings and was so hungry for God he created a disturbance and church members asked him to stop. He went to prayer and prayed for four days. Finally he was getting ready to head home and the vicar's wife prayed for him and he fell under the power of God and spoke in tongues. Everything changed after that. He would walk by people and they would come under the conviction of the Holy Spirit and be saved. He began to see miracles and healings and the glory of God would fall when he prayed and preached.

Smith had to respond to the many calls that came in and gave up his business for the ministry. Polly unexpectedly died in 1913, and this was a real blow to Smith. He prayed for her and commanded that death release her. She did arise but said "Smith - the Lord wants me." His heartbroken response was "If the Lord wants you, I will not hold you". She had been his light and joy for all the years of their marriage, and he grieved deeply over the loss. After his wife was buried he went to her grave, feeling like he wanted to die. When God told him to get up and go Smith told him only if you "give to me a double portion of the Spirit – my wife’s and my own – I would go and preach the Gospel. God was gracious to me and answered my request.” His daughter Alice and son-in-law James Salter began to travel with him to handle his affairs.

Smith would pray and the blind would see, and the deaf were healed, people came out of wheelchairs, and cancers were destroyed. One remarkable story is when He prayed for a woman in a hospital. While he and a friend were praying she died. He took her out of the bed stood her against the wall and said "in the name of Jesus I rebuke this death". Her whole body began to tremble. The he said "in the name of Jesus walk", and she walked. Everywhere he would go he would teach and then show the power of God. He began to receive requests from all over the world. He taught in Europe, Asia, New Zealand and many other areas. When the crowds became very large he began a "wholesale healing". He would have everyone who needed healing lay hands on themselves and then he would pray. Hundreds would be healed at one time.

Over Smith's ministry it was confirmed that 14 people were raised from the dead. Thousands were saved and healed and he impacted whole continents for Christ. Smith died on March 12, 1947 at the funeral of his dear friend Wilf Richardson. His ministry was based on four principles " First, read the Word of God. Second, consume the Word of God until it consumes you. Third believe the Word of God. Fourth, act on the Word."

an address to young converts

As one who for fifty years has known the Lord, and has laboured in word and doctrine, I ought to be able, in some little measure, to lend a helping hand to these younger believers. And if God will only condescend to use the acknowledgment of my own failures to which I refer, and of my experience, as a help to others in walking on the road to heaven, I trust that your coming here will not be in vain. This was the very purpose of my leaving home—that I might help these dear young brethren. The Manner of Reading the Word One of the most deeply important points is that of attending to the careful, prayerful reading of the Word of God, and meditation thereon. I would therefore ask your particular attention to one verse in the Epistle of Peter, where we are especially exhorted by the Holy Ghost through the apostle, regarding this subject. For the sake of the connection, let us read the first verse, "Wherefore laying aside all malice, and all guile and hypocrisies, and envies, and all evil-speakings, as new-born babes, desire the sincere milk of the Word, that ye may grow thereby; if so be ye have tasted that the Lord is gracious." (1 Peter 2:2) The particular point to which I refer is contained in the second verse, "as new-born babes, desire the sincere milk of the Word." As growth in the natural life is attained by proper food, so in the spiritual life, if we desire to grow, this growth is only to be attained through the instrumentality of the Word of God. It is not stated here, as some might be very willing to say, that "the reading of the Word may be of importance under some circumstances." Nor is it stated that you may gain profit by reading the statement which is made here; it is of the 'Word,' and of the Word alone, that the apostle speaks, and nothing else. Cleave to the Word You say that the reading of this tract or of that book often does you good. I do not question it. Nevertheless, the instrumentality which God has been specially pleased to appoint and to use is that of the Word itself; and just in the measure in which the disciples of the Lord Jesus Christ attend to this, they will become strong in the Lord; and in so far as it is neglected, so far will they be weak. There is such a thing as babes being neglected, and what is the consequence? They never become healthy men or women, because of that early neglect. Perhaps—and it is one of the most hurtful forms of this neglect—they obtain improper food, and therefore do not attain the full vigour of maturity. So with regard to the divine life. It is a most deeply important point, that we obtain right spiritual food at the very beginning of that life. What is that food? It is "the sincere milk of the Word;" that is the proper nourishment for the strengthening of the new life. Listen, then, my dear brethren and sisters, to some advice with regard to the Word. Consecutive Reading First of all, it is of the utmost moment that we read regularly through the Scripture. We ought not to turn over the Bible, and pick out chapters as we please here and there, but we should read it carefully and regularly through. I speak advisedly, and as one who has known the blessedness of thus reading the Word for the last forty-six years. I say forty-six years, because for the first four years of my Christian life I did not carefully read the Word of God. I used to read a tract, or an interesting book; but I knew nothing of the power of the Word. I read very little of it, and the result was, that, although a preacher then, yet I made no progress in the divine life. And why? Just for this reason—I neglected the Word of God. But it pleased God, through the instrumentality of a beloved Christian brother, to rouse in me an earnestness about the Word, and ever since then I have been a lover of it. Let me, then, press upon you my first point, that of attending regularly to reading through the Scriptures. I do not suppose that you all need the exhortation. Many, I believe, have already done so; but I speak for the benefit of those who have not. To those I say, My dear friends, begin at once. Begin with the Old Testament, and when you have read a chapter or two, and are about to leave off, put a mark that you may know where you have left off. I speak in all simplicity for the benefit of those who may be young in the divine life. The next time you read, begin the New Testament, and again put a mark where you leave off. And thus go on, always reading alternately the Old and the New Testaments. Thus, by little and little, you will read through the whole Bible; and when you have finished, begin again at the beginning. The Connection of Scripture Why is this so deeply important? Simply that we may see the connection between one book and another of the Bible, and between one chapter and another. If we do not read in this consecutive way, we lose a great part of what God has given to instruct us. Moreover, if we are children of God, we should be well acquainted with the whole revealed will of God—the whole of the Word. "All Scripture is given by inspiration, and is profitable." (2 Timothy 3:16) And much may be gained by thus carefully reading through the whole of the revealed will of God. Suppose a rich relative were to die, and leave us, perhaps, some land, or houses, or money, should we be content with reading only the clauses that affected us particularly? No, we would be careful to read the whole will right through. How much more, then, with regard to the revealed will of God ought we to be careful to read it through, and not merely one and another of the chapters or books. Another Benefit of this Consecutive Reading And this careful reading of the Word of God has this advantage, that it keeps us from making a system of doctrine of our own, and from having our own particular favourite views, which is very pernicious. We often are apt to lay too much stress on certain views of the truth which affect us particularly. The will of the Lord is, that we should know His whole revealed mind. Again variety in the things of God is of great moment. And God has been pleased to give us this variety in the highest degree; and the child of God, who follows out this plan, will be able to take an interest in every part of the Word. Suppose one says, "Let us read in Leviticus." Very well, my brother. Suppose another says, "Let us read in the prophecy of Isaiah." Very well, my brother. And another will say, "Let us read in the Gospel according to Matthew." Very well, my brother; I can enjoy them all; and whether it be in the Old Testament, or in the New Testament, whether in the Prophets, the Gospels, the Acts, or the Epistles, I should welcome it, and be delighted to welcome the reading and study of any part of the divine Word. Specially Beneficial to the Labourer for Christ And this will be of particular advantage to us, in case we should become labourers in Christ's vineyard; because in expounding the Word, we shall be able to refer to every part of it. We shall equally enjoy the reading of the Word, whether of the Old or the New Testament, and shall never get tired of it. I have, as before stated, known the blessedness of this plan for forty-six years, and though I am now nearly seventy years of age, and though I have been converted for nearly fifty years, I can say, by the grace of God, that I more than ever love the Word of God, and have greater delight than ever in reading it. And though I have read the Word nearly a hundred times right through, I have never got tired of reading it, and this is more especially through reading it regularly, consecutively, day by day, and not merely reading a chapter here and there, as my own thoughts might have led me to do. Reading the Word Prayerfully Again, we should read the Scripture prayerfully, never supposing that we are clever enough or wise enough to understand God's Word by our own wisdom. In all our reading of the Scriptures let us seek carefully to have the help of the Holy Spirit; let us ask, for Jesus' sake, that He will enlighten us. He is willing to do it. I will tell you how it fared with me at the very first; it may be for your encouragement. It was in the year 1829, when I was living in Hackney. My attention had been called to the teaching of the Spirit by a dear brother of experience. "Well," I said, "I will try this plan; and will give myself, after prayer, to the careful reading of the Word of God, and to meditation, and I will see how much the Spirit is willing to teach me in this way." An Illustration of This I went accordingly to my room, and locked my door, and putting the Bible on a chair, I went down on my knees at the chair. There I remained for several hours in prayer and meditation over the Word of God; and I can tell you that I learned more in those three hours which I spent in this way, than I had learned for many months previously. I thus obtained the teaching of the Divine Spirit, and I cannot tell you the blessedness which it was to my own soul. I was praying in the Spirit, and putting my trust in the power of the Spirit, as I had never done before. You cannot, therefore, be surprised at my earnestness in pressing this upon you, when you have heard how precious to my heart it was, and how much it helped me. Meditate on the Word But again, it is not enough to have prayerful reading only, but we must also meditate on the Word. As in the instance I have just referred to, kneeling before the chair, I meditated on the Word. It was not simply reading it, not simply praying over it. It was all that, but, in addition it was pondering over what I had read. This is deeply important. If you merely read the Bible, and no more, it is just like water running in at one side and out at the other. In order to be really benefited by it, we must meditate on it. We cannot all of us, of course, spend many hours, or even one or two hours each day in this manner. Our business demands our attention. Yet, however short the time you can afford, give it regularly to reading, prayer and meditation over the Word, and you will find it will well repay you. Make the Meditation Personal In connection with this, we should always read and meditate over the Word of God, with reference to ourselves and our own heart. This is deeply important, and I cannot press it too earnestly upon you. We are apt often to read the Word with reference to others. Parents read it in reference to their children, children for their parents; evangelists read it for their congregations, Sunday-school teachers for their classes. Oh! this is a poor way of reading the Word; if read in this way, it will not profit. I say it deliberately and advisedly; the sooner it is given up, the better for your own souls. Read the Word of God always with reference to your own heart, and when you have received the blessing in your own heart, you will be able to communicate it to others. Whether you labour as evangelists, as pastors, or as visitors, superintendents of Sunday schools, or teachers, tract distributors or in whatever other capacity you may seek to labour for the Lord, be careful to let the reading of the Word be with distinct reference to your own heart. Ask yourselves, how does this suit me, either for instruction, for correction, for exhortation, or for rebuke? How does this affect me? If you thus read, and get the blessing in your own soul, how soon it will flow out to others! Read in Faith Another point. It is of the utmost moment in reading the Word of God, that the reading should be accompanied with faith. "The word preached did not profit them, not being mixed with faith in them that heard it." (Hebrews 4:2) As with the preaching, so with the reading it must be mixed with faith. Not simply reading it as you would read a story, which you may receive or not; not simply as a statement, which you may credit or not; or as an exhortation, to which you may listen or not; but as the revealed will of the Lord: that is, receiving it with faith. Received thus, it will nourish us, and we shall reap benefit. Only in this way will it benefit us; and we shall gain from it health and strength in proportion as we receive it with real faith. Be Doers of the Word Lastly, if God does bless us in reading His Word, He expects that we should be obedient children, and that we should accept the Word as His will, and carry it into practice. If this be neglected, you will find that the reading of the Word, even if accompanied by prayer, meditation and faith, will do you little good. God does expect us to be obedient children, and will have us practise what He has taught us. The Lord Jesus Christ says: "If ye know these things, happy are ye if ye do them." (John 13:17) And in the measure in which we carry out what our Lord Jesus taught, so much in measure are we happy children. And in such measure only can we honestly look for help from our Father, even as we seek to carry out His will. If there is one single point I would wish to have spread all over this country, and over the whole world, it is just this, that we should seek, beloved Christian friends, not to be hearers of the Word only, but "doers of the Word." (James 1:22) I doubt not that many of you have sought to do this already, but I speak particularly to those younger brethren and sisters who have not yet learned the full force of this. Oh! seek to attend earnestly to this, it is of vast importance. Satan will seek with much earnestness to put aside the Word of God; but let us seek to carry it out and to act upon it. The Word must be received as a legacy from God, which has been communicated to us by the Holy Ghost. Therefore, it is the will of the Lord that we should always own our dependence upon Him in prayer. The Fullness of the Revelation Given in His Word And remember that, to the faithful reader of this blessed Word, it reveals all that we need to know about the Father, all that we need to know about the Lord Jesus Christ, all about the power of the Spirit, all about the world that lieth in the wicked one, all about the road to heaven, and the blessedness of the world to come. In this blessed book we have the whole Gospel, and all rules necessary for our Christian life and warfare. Let us see than that we study it with our whole heart and with prayer, meditation, faith and obedience. Prayer The next point on which I will speak for a few moments has been more or less referred to already, it is that of prayer. You might read the Word and seem to understand it very fully, yet if you are not in the habit of waiting continually upon God, you will make little progress in the divine life. We have not naturally in us any good thing; and cannot expect, save by the help of God, to please Him. The blessed Lord Jesus Christ gave us an example in this particular. He gave whole nights to prayer. We find Him on the lonely mountain engaged by night in prayer. And as in every way He is to be an example to us, so, in particular, on this point. He is an example to us. The old evil corrupt nature is still in us, though we are born again; therefore, we have to come in prayer to God for help. We have to cling to the power of the Mighty One. Concerning everything, we have to pray. Not simply when great troubles come, when the house is on fire, or a beloved wife is on the point of death, or dear children are laid down in sickness—not simply at such times, but also in little things. From the very early morning, let us make everything a matter of prayer, and let it be so throughout the day, and throughout our whole life. A Christian lady said lately, that thirty-five years ago she heard me speak on this subject in Devonshire; and that then I referred to praying about little things. I had said, that suppose a parcel came to us, and it should prove difficult to untie the knot, and you cannot cut it; then you should ask God to help you, even to untie the knot. I myself had forgotten the words, but she has remembered them, and the remembrance of them, she said, had been a great help to her again and again. So I would say to you, my beloved friends, there is nothing too little to pray about. In the simplest things connected with our daily life and walk, we should give ourselves to prayer; and we shall have the living, loving Lord Jesus to help us. Even in the most trifling matters I give myself to prayer and often in the morning, even ere I leave my room I have two or three answers to prayer in this way. Young believers, in the very outset of the divine life in your souls, learn, in childlike simplicity, to wait upon God for everything! Treat the Lord Jesus Christ as your personal Friend, able and willing to help you in everything. How blessed it is to be carried in His loving arms all the day long! I would say, that the divine life of the believer is made up of a vast number of little circumstances and little things. Every day there comes before us a variety of little trials, and if we seek to put them aside in our own strength and wisdom, we shall quickly find that we are confounded. But if, on the contrary, we take everything to God, we shall be helped, and our way shall be made plain. Thus our life will be a happy life! A Word to the Unconverted I am here tonight addressing believers, those who have felt the burden of their sins, and have accepted Christ as their Saviour, and who now through Him have peace with God and seek to glorify Him. But if there be any here who are still in their sins, in a state of alienation from God, let me say, if they die in this state, the terrible punishment of sin must fall upon them. Unless their sins are pardoned, and they are made fit for the Divine presence, they can never enter heaven. But, dear friends, Christ came to save the lost, and as sinners, you are lost, and you have no power of your own to save yourselves. The world talks of turning over a new leaf, but that will not satisfy Divine justice. Sin must be punished, or God's righteousness would be set aside. Jesus came into the world to bear that punishment. He has borne it in our room and stead. He has suffered for us. Now what God looks for from us is, that we accept Jesus as our Saviour, and put our trust in Him for the salvation of our souls. Whosoever looks really and entirely to Him shall assuredly be saved. Let his sins be ever so many, he shall have the forgiveness of them all. Nay, more, he will be accepted by God as His child. He will become an heir of God and a joint-heir with Christ. Oh, what great and glorious salvation, so freely given! May it be as thankfully accepted! And may we who rejoice in Him stand boldly out and confess Christ, and work for Him. May we not be half-hearted, but be valiant soldiers of Christ. Let us be decided for Christ. Let us walk as in God's sight, in holy, peaceful, happy fellowship with Him, in the enjoyment of that nearness into which we are brought in Christ. Oh, the blessedness of this privilege of living near to God in this life! May we, then, seek His guidance in everything, so that we may be a blessing to others, and thus we shall be greatly blessed in our own souls. From a sermon preached at Mildmay Conference Hall (date unknown) by George Müller.

-480.webp)