About the Book

"Your Best Life Now" by Joel Osteen is a self-help book that encourages readers to have a positive outlook on life and believe that they can achieve success and happiness by changing their thoughts and actions. Osteen advises readers to set goals, believe in their potential, and have faith in God's plan for their lives in order to live their best life.

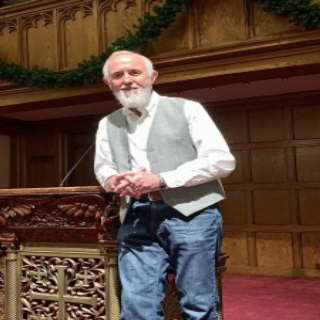

Nik Ripken

Nik and Ruth, with 3 children, served for over 32 years obeying Christ’s command to share Jesus across the globe. After 7 years in Malawi & South Africa, they moved to Nairobi, Kenya to begin work among the Somali people (1991-1997). Since that time (1998-2013) they have journeyed globally among people whom, when they gave their lives to Jesus, faced increasing persecution for their faith.

The Ripkens and their teams served throughout the Horn of Africa within famine and war zones; resettling refugees, providing famine relief, and operating mobile medical clinics. Formerly Muslims, many Somali believers, suffered for their faith. Most were martyred. Near the end of the Ripken’s tenure among the Somalis, their 16-year-old son died of an asthma attack on Easter Sunday morning. He’s buried at the school from which the other Ripken children graduated.

One year later, the Holy Spirit led the Ripkens to begin a global pilgrimage to learn from believers in persecution how to recapture a biblical missiology of witness and house-church planting in the midst of persecution and martyrdom. Most of all, believers in persecution modeled for the Ripkens how to trust Jesus completely. Many of these lessons have been lost or forgotten by the church in the West.

Currently the Ripkens have interviewed over 600 believers in persecution, exceeding 72 countries. Sitting at their feet, the Ripkens learned from the suffering church how to thrive amidst suffering, not merely survive. The Ripkens, using everything they’ve learned from believers in persecution are creating resources as gifts from the church to the church. To date they have created articles, books, a music CD, a documentary, workshops, and other tools that allow the church in persecution to teach the church in the West about its biblical heritage of both crucifixion and resurrection. A teaching DVD is included in future plans. All these tools are designed to challenge believers to boldly follow Jesus, sharing their faith with others-no matter the cost.

Nik and Ruth, with 3 children, served for over 32 years obeying Christ’s command to share Jesus across the globe. After 7 years in Malawi & South Africa, they moved to Nairobi, Kenya to begin work among the Somali people (1991-1997). Since that time (1998-2013) they have journeyed globally among people whom, when they gave their lives to Jesus, faced increasing persecution for their faith.

The Ripkens and their teams served throughout the Horn of Africa within famine and war zones; resettling refugees, providing famine relief, and operating mobile medical clinics. Formerly Muslims, many Somali believers, suffered for their faith. Most were martyred. Near the end of the Ripken’s tenure among the Somalis, their 16-year-old son died of an asthma attack on Easter Sunday morning. He’s buried at the school from which the other Ripken children graduated.

One year later, the Holy Spirit led the Ripkens to begin a global pilgrimage to learn from believers in persecution how to recapture a biblical missiology of witness and house-church planting in the midst of persecution and martyrdom. Most of all, believers in persecution modeled for the Ripkens how to trust Jesus completely. Many of these lessons have been lost or forgotten by the church in the West.

Currently the Ripkens have interviewed over 600 believers in persecution, exceeding 72 countries. Sitting at their feet, the Ripkens learned from the suffering church how to thrive amidst suffering, not merely survive. The Ripkens, using everything they’ve learned from believers in persecution are creating resources as gifts from the church to the church. To date they have created articles, books, a music CD, a documentary, workshops, and other tools that allow the church in persecution to teach the church in the West about its biblical heritage of both crucifixion and resurrection. A teaching DVD is included in future plans. All these tools are designed to challenge believers to boldly follow Jesus, sharing their faith with others-no matter the cost.

10 Times Denzel Washington was Candid about His Christian Faith

Throughout his career, actor Denzel Washington has been open about his faith. Most recently, Washington reportedly offered some Biblical-inspired wisdom to actor Will Smith after he slapped comedian Chris Rock at the 2022 Oscars. Here's a look at 10 times Washington has talked about faith and its impact on his life and career. Denzel Washington, Washington shares his supernatural experience coming to Christ 1. Oscars 2022 on Smith-Rock Incident "Denzel said to me a few minutes ago, he said, 'At your highest moment, be careful— that's when the devil comes for you,'" Smith said during the Oscars while accepting his award. Smith was referring to the commercial break when Washington approached Smith after Smith rushed on stage to slap Rock for joking about Smith's wife. Washington's statement to Smith refers to 1 Peter 5:8, which says, "Be alert and of sober mind. Your enemy the devil prowls around like a roaring lion looking for someone to devour." 2. Showtime's Desus & Mero Podcast 2022 on talent "One of the most important lessons in life that you should know is to remember to have an attitude of gratitude, of humility, understand where the gift comes from," Washington said. "It's not mine, it's been given to me by the grace of God." 3. New York Times 2021 Interview on spiritual warfare "This is spiritual warfare. So, I'm not looking at it from an earthly perspective," Washington told the New York Times. "If you don't have a spiritual anchor, you'll be easily blown by the wind, and you'll be led to depression. "The enemy is the inner me," Washington added. "The Bible says in the last days – I don't know if it's the last days, it's not my place to know – but it says we'll be lovers of ourselves. The number one photograph today is a selfie, 'Oh, me at the protest.' 'Me with the fire.' 'Follow me.' 'Listen to me.'" 4. 2021 "The Better Man Event" on the role of a man "The John Wayne formula is not quite a fit right now. But strength, leadership, power, authority, guidance, [and] patience are God's gift to us as men. We have to cherish that, not abuse it. "I hope that the words in my mouth and the meditation of my heart are pleasing in God's sight, but I'm human. I'm just like you," he said. 5. 2021 Religion News Service Interview on how his faith impacted his film, "Journal for Jordan" "The spirit of God is throughout the film. Charles is an angel. I'm a believer. Dana's a believer. So that was a part of every decision, hopefully, that I tried to make. I wanted to please God, and I wanted to please Charles, and I wanted to please Dana." "I am a member, also a member of the (Cultural Christian Center) out here in New York. I have more than one spiritual leader in my life. So there's different people I talk to, and I try to make sure I try to put God first in everything. I was reading something this morning in my meditation about selfishness and how the only way to true independence is complete dependence on the Almighty." 6. Instagram Live with Pastor A.R. Bernard of Christian Cultural Center on his salvation "I was filled with the Holy Ghost, and it scared me. I said, 'Wait a minute, I didn't want to go this deep, I want to party,'" Washington said of the time he gave his life to Christ. "I went to church with Robert Townsend, and when it came time to come down to the altar, I said, 'You know this time, I'm just going to go down there and give it up and see what happens. I went in the prayer room and gave it up and let go and experienced something I've never experienced in my life." 7. 2017 The Christian Post Interview on advice for millennials "I would say to your generation – find a way to work together because this is a very divisive, angry time you're living in, unfortunately, because we didn't grow up like that," he said. "I pray for your generation," he added. "What an opportunity you have! Don't be depressed by it because we have to go through this, we're here now. You can't put that thing back in the box." 8. 2017 Screen Actors Guild Awards "I'm a God-fearing man. I'm supposed to have faith, but I didn't have faith," he said, according to Faith Wire. "God bless you all, all you other actors." 9. 2015 Church of God in Christ's Charity Banquet "Through my work, I have spoken to millions of people. In 2015, I said I'm no longer just going to speak through my work. I'm going to make a conscious effort to get up and speak about what God has done for me." 10. 2007 Reader's Digest Interview on his faith "I read the Bible every day. I'm in my second pass-through now, in the Book of John. My pastor told me to start with the New Testament, so I did, maybe two years ago. Worked my way through it, then through the Old Testament. Now I'm back in the New Testament. It's better the second time around." Amanda Casanova ChristianHeadlines.com Contributor