Others like the place of prayer in evangelism Features >>

God's Generals - The Healing Evangelists

Reaching The Lost: Evangelism

The Power Of Tongues

The Purpose Of Pentecost

The Voice Of One Crying

The Harvest. Updated And Expanded

The Case For The Resurrection

The Winds Of God Bring Revival

The Case For The Resurrection Of Jesus

The Reason For God: Belief In An Age Of Scepticism

About the Book

"The Place of Prayer in Evangelism" by R. A. Torrey emphasizes the importance of prayer in the process of evangelism. Torrey explains that prayer is essential for both the evangelist and the person being reached, as it opens the door for the work of the Holy Spirit in transforming hearts and minds. Through personal anecdotes and biblical examples, Torrey illustrates how prayer can lead to powerful and effective evangelism efforts that ultimately bring people to faith in Christ.

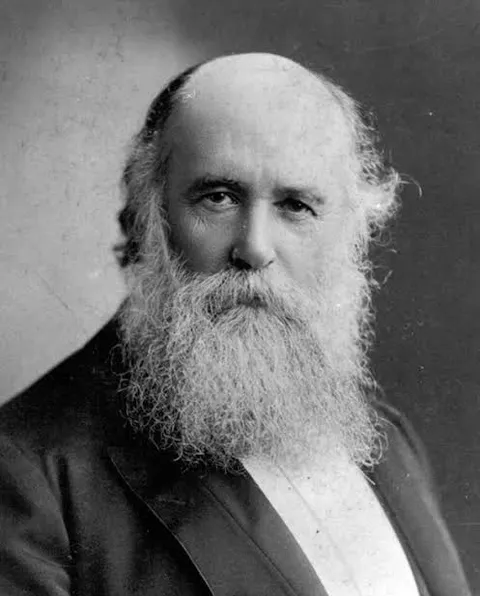

John Alexander Dowie

By John Alexander Dowie (1847 – 1907)

I sat in my study in the parsonage of the Congregational Church at Newtown, a suburb of the beautiful city of Sydney, Australia. My heart was very heavy, for I had visited the sick and dying beds of more than thirty of my flock, and I had cast the dust to its kindred dust into more than forty graves within a few weeks. Where, oh where, was He Who used to heal His suffering children? No prayer for healing seemed to reach His ear, and yet I knew His hand had not been shortened. Still it did not save from death even those for whom there was so much in life to live for God and others. Strong men, fathers, good citizens, and more than all, true Christians sickened with a putrid fever, suffered nameless agonies, passed into delirium, sometimes with convulsions, and then died.

Oh, what aching voids were left in many a widowed or orphaned heart. There were many homes where, one by one, the little children, the youths and the maidens lay stricken, and after a hard struggle with the foul disease, they too, lay cold and dead. It seemed sometimes as if I could almost hear the triumphant mockery of evil ringing in my ear whilst I spoke to the bereaved ones the words of Christian hope and consolation. Disease, the foul offspring of its father, Satan, and its mother Sin, was defiling and destroying the earthly temples of God’s children and there was no deliverance.

There I sat with sorrow-bowed head for my afflicted people, until the bitter tears came to relieve my burning heart. Then I prayed for some message, and oh, how I longed to hear some words from Him Who wept and sorrowed for the suffering long ago, a Man of Sorrows and Sympathies. The words of the Holy Ghost inspired In Acts 10:38, stood before me all radiant with light, revealing Satan as the Defiler, and Christ as the Healer. My tears were wiped away, my heart strong, I saw the way of healing, and the door thereto was opened wide, so I said, “God help me now to preach the Word to all the dying around, and tell them how Satan still defiles, and Jesus still delivers, for He is just the same today.”

A loud ring and several raps at the outer door, a rush of feet, and there at my door stood two panting messengers who said, “Oh, come at once, Mary is dying; come and pray. “With just a feeling as a shepherd has who hears that his sheep are being torn from the fold by a cruel wolf, I rushed from my house, ran without my hat down the street, and entered the room of the dying maiden. There she lay groaning and grinding her clenched teeth in the agony of the conflict with the destroyer. The white froth, mingled with her blood, oozing from her pale and distorted mouth. I looked at her and then my anger burned. “Oh,” I thought, “for some sharp sword of heavenly temper keen to slay this cruel foe who is strangling that lovely maiden like an invisible serpent, tightening his deadly coils for a final victory.”

In a strange way, It came to pass; I found the sword I needed was in my hands, and in my hand I hold it still and never will I lay It down. The doctor, a good Christian man, was quietly walking up and down the room, sharing the mother’s pain and grief. Presently he stood at my side and said, “Sir, are not God’s ways mysterious?” Instantly the sword was flashed in my hand, the Spirit’s sword, the Word of God. “God’s way?!” I said, pointing to the scene of conflict, “How dare you call that God’s way of bringing His children home from earth to Heaven? No sir, that is the devil’s work and it is time we called on Him Who came to destroy the work of the devil, to slay that deadly foul destroyer, and to save this child. Can you pray, Doctor, can you pray the prayer of faith that saves the sick?” At once, offended at my words, my friend was changed, and saying,” You are too much excited, sir, it is best to say ‘God’s will be done,’” and he left the room.

Excited?! The word was quite inadequate for I was almost frenzied with divinely imparted anger and hatred of that foul destroyer, disease, which was doing Satan’s will. “It is not so,” I exclaimed, “no will of God sends such cruelty, and I shall never say ‘God’s will be done’ to Satan’s works, which God’s own Son came to destroy, and this is one of them.” Oh, how the Word of God was burning in my heart: “Jesus of Nazareth went about doing good, and healing all that were oppressed of the devil; for God was with Him.” And was not God with me? And was not Jesus there and all His promises true? I felt that it was even so, and turning to the mother I inquired,” Why did you send for me?” To which she answered, “Do pray, oh pray for her that God may raise her up.” So we prayed.

What did I say? It may be that I cannot recall the words without mistake, but words are in themselves of small importance. The prayer of faith may be a voiceless prayer, a simple heartfelt look of confidence into the face of Christ. At such moment, words are few, but they mean much, for God is looking at the heart. Still, I can remember much of that prayer unto this day, and asking God to aid, I will attempt to recall it. I cried, “Our Father, help! and Holy Spirit, teach me how to pray. Plead Thou for us, oh, Jesus, Savior, Healer, Friend, our Advocate with God the Father. Hear and heal, Eternal One! From all disease and death, deliver this sweet child of yours. I rest upon the Word. We claim the promise now. The Word is true, ‘I am the Lord that heals thee.’ Then heal her now. The Word is true, ‘I am the Lord, I change not.’ Unchanging God, then prove Yourself the healer now. The Word is true. ‘These signs shall follow them that believe in My Name, they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover.’ And I believe and I lay hands in Jesus’ Name on her and claim this promise now. Your Word is true. ‘The prayer of faith shall save the sick. Trusting in You alone. I cry. Oh, save her now, for Jesus’ sake. Amen!”

Then, the maid lay in sleep so deep and sweet that the mother asked in a low whisper, “Is she dead?” “No,” I answered, in a whisper lower still. “Mary will live; the fever is gone. She is perfectly well and sleeping as an infant sleeps.” I was smoothing the long dark hair from her now peaceful brow, and feeling the steady pulsation of her heart and cool moist hands. I saw that Christ had heard, and that once more, as long ago in Peter’s house, “He touched her and the fever left her.” Turning to the nurse, I said, “Get me at once, please, a cup of cocoa and several slices of bread and butter.” Beside the sleeping maid we sat quietly and almost silently until the nurse returned, and then I bent over her and snapping my fingers called, “Mary!”

Instantly she woke, smiled and said, “Oh, sir, when did you come? I have slept so long;” then stretching her arms out to meet her mother’s embrace, she said, “Mother, I feel so well.” “And hungry, too?” I asked, pouring some of the cocoa in a saucer and offering it to her when cooled by my breath. “Yes, hungry too,” she answered with a little laugh, and drank and ate again, and yet again until all was gone. In a few minutes, she fell asleep, breathing easily and softly. Quietly thanking God. We left her bed and went to the next room where her brother and sister also lay sick of the same fever. With these two, we prayed and they were healed too. The following day all three were well and in a week or so they brought me a little letter and a gift of gold, two sleeve links with my monogram, which I wore for many years. As I went away from the home where Christ as the Healer had been victorious, I could not but have somewhat in my heart of the triumphant song that rang through Heaven, and yet I was not a little amazed at my own strange doings, and still more at my discovery that He is just the same today.

Excerpt from the Sermons of John Alexander Dowie Champions of Faith by Gordon Lindsay

By John Alexander Dowie (1847 – 1907)

I sat in my study in the parsonage of the Congregational Church at Newtown, a suburb of the beautiful city of Sydney, Australia. My heart was very heavy, for I had visited the sick and dying beds of more than thirty of my flock, and I had cast the dust to its kindred dust into more than forty graves within a few weeks. Where, oh where, was He Who used to heal His suffering children? No prayer for healing seemed to reach His ear, and yet I knew His hand had not been shortened. Still it did not save from death even those for whom there was so much in life to live for God and others. Strong men, fathers, good citizens, and more than all, true Christians sickened with a putrid fever, suffered nameless agonies, passed into delirium, sometimes with convulsions, and then died.

Oh, what aching voids were left in many a widowed or orphaned heart. There were many homes where, one by one, the little children, the youths and the maidens lay stricken, and after a hard struggle with the foul disease, they too, lay cold and dead. It seemed sometimes as if I could almost hear the triumphant mockery of evil ringing in my ear whilst I spoke to the bereaved ones the words of Christian hope and consolation. Disease, the foul offspring of its father, Satan, and its mother Sin, was defiling and destroying the earthly temples of God’s children and there was no deliverance.

There I sat with sorrow-bowed head for my afflicted people, until the bitter tears came to relieve my burning heart. Then I prayed for some message, and oh, how I longed to hear some words from Him Who wept and sorrowed for the suffering long ago, a Man of Sorrows and Sympathies. The words of the Holy Ghost inspired In Acts 10:38, stood before me all radiant with light, revealing Satan as the Defiler, and Christ as the Healer. My tears were wiped away, my heart strong, I saw the way of healing, and the door thereto was opened wide, so I said, “God help me now to preach the Word to all the dying around, and tell them how Satan still defiles, and Jesus still delivers, for He is just the same today.”

A loud ring and several raps at the outer door, a rush of feet, and there at my door stood two panting messengers who said, “Oh, come at once, Mary is dying; come and pray. “With just a feeling as a shepherd has who hears that his sheep are being torn from the fold by a cruel wolf, I rushed from my house, ran without my hat down the street, and entered the room of the dying maiden. There she lay groaning and grinding her clenched teeth in the agony of the conflict with the destroyer. The white froth, mingled with her blood, oozing from her pale and distorted mouth. I looked at her and then my anger burned. “Oh,” I thought, “for some sharp sword of heavenly temper keen to slay this cruel foe who is strangling that lovely maiden like an invisible serpent, tightening his deadly coils for a final victory.”

In a strange way, It came to pass; I found the sword I needed was in my hands, and in my hand I hold it still and never will I lay It down. The doctor, a good Christian man, was quietly walking up and down the room, sharing the mother’s pain and grief. Presently he stood at my side and said, “Sir, are not God’s ways mysterious?” Instantly the sword was flashed in my hand, the Spirit’s sword, the Word of God. “God’s way?!” I said, pointing to the scene of conflict, “How dare you call that God’s way of bringing His children home from earth to Heaven? No sir, that is the devil’s work and it is time we called on Him Who came to destroy the work of the devil, to slay that deadly foul destroyer, and to save this child. Can you pray, Doctor, can you pray the prayer of faith that saves the sick?” At once, offended at my words, my friend was changed, and saying,” You are too much excited, sir, it is best to say ‘God’s will be done,’” and he left the room.

Excited?! The word was quite inadequate for I was almost frenzied with divinely imparted anger and hatred of that foul destroyer, disease, which was doing Satan’s will. “It is not so,” I exclaimed, “no will of God sends such cruelty, and I shall never say ‘God’s will be done’ to Satan’s works, which God’s own Son came to destroy, and this is one of them.” Oh, how the Word of God was burning in my heart: “Jesus of Nazareth went about doing good, and healing all that were oppressed of the devil; for God was with Him.” And was not God with me? And was not Jesus there and all His promises true? I felt that it was even so, and turning to the mother I inquired,” Why did you send for me?” To which she answered, “Do pray, oh pray for her that God may raise her up.” So we prayed.

What did I say? It may be that I cannot recall the words without mistake, but words are in themselves of small importance. The prayer of faith may be a voiceless prayer, a simple heartfelt look of confidence into the face of Christ. At such moment, words are few, but they mean much, for God is looking at the heart. Still, I can remember much of that prayer unto this day, and asking God to aid, I will attempt to recall it. I cried, “Our Father, help! and Holy Spirit, teach me how to pray. Plead Thou for us, oh, Jesus, Savior, Healer, Friend, our Advocate with God the Father. Hear and heal, Eternal One! From all disease and death, deliver this sweet child of yours. I rest upon the Word. We claim the promise now. The Word is true, ‘I am the Lord that heals thee.’ Then heal her now. The Word is true, ‘I am the Lord, I change not.’ Unchanging God, then prove Yourself the healer now. The Word is true. ‘These signs shall follow them that believe in My Name, they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover.’ And I believe and I lay hands in Jesus’ Name on her and claim this promise now. Your Word is true. ‘The prayer of faith shall save the sick. Trusting in You alone. I cry. Oh, save her now, for Jesus’ sake. Amen!”

Then, the maid lay in sleep so deep and sweet that the mother asked in a low whisper, “Is she dead?” “No,” I answered, in a whisper lower still. “Mary will live; the fever is gone. She is perfectly well and sleeping as an infant sleeps.” I was smoothing the long dark hair from her now peaceful brow, and feeling the steady pulsation of her heart and cool moist hands. I saw that Christ had heard, and that once more, as long ago in Peter’s house, “He touched her and the fever left her.” Turning to the nurse, I said, “Get me at once, please, a cup of cocoa and several slices of bread and butter.” Beside the sleeping maid we sat quietly and almost silently until the nurse returned, and then I bent over her and snapping my fingers called, “Mary!”

Instantly she woke, smiled and said, “Oh, sir, when did you come? I have slept so long;” then stretching her arms out to meet her mother’s embrace, she said, “Mother, I feel so well.” “And hungry, too?” I asked, pouring some of the cocoa in a saucer and offering it to her when cooled by my breath. “Yes, hungry too,” she answered with a little laugh, and drank and ate again, and yet again until all was gone. In a few minutes, she fell asleep, breathing easily and softly. Quietly thanking God. We left her bed and went to the next room where her brother and sister also lay sick of the same fever. With these two, we prayed and they were healed too. The following day all three were well and in a week or so they brought me a little letter and a gift of gold, two sleeve links with my monogram, which I wore for many years. As I went away from the home where Christ as the Healer had been victorious, I could not but have somewhat in my heart of the triumphant song that rang through Heaven, and yet I was not a little amazed at my own strange doings, and still more at my discovery that He is just the same today.

Excerpt from the Sermons of John Alexander Dowie Champions of Faith by Gordon Lindsay

the deadly deceit in material desires

Bible study often exposes us. As I sat in a Bible study recently, the leader asked our group how we heard Jesus’s voice and how we follow, like he says in John 10:27: “My sheep hear my voice, and I know them, and they follow me.” One woman sitting next to me measured the voice of God in the many blessings of her life — a new house purchased without difficulty, an old house sold without stress. She was now enjoying life in her dream home in the warm, dry climate of her dreams. And all thanks to a painless move. She gave evidence for how smoothly her life was moving along, like dominoes falling perfectly in order. As I sat there listening, I couldn’t help but feel troubled. I knew that not a few women around us were following Christ through troubled marriages, battles with cancer, or the grief of lost babies. Some faced the drone of unceasing financial hardships — the exact opposite of how some of us define God’s blessing on our lives. And yet we who are struggling can listen for Jesus’s voice with desperation and longing. We can desire to follow him as much — perhaps more — than the materially blessed. Blessing’s Bluff A smile and an open Bible can press down so hard on raw hurt when we measure God’s blessing with material prosperity. The effect is something I’ve heard expressed by many and have seen dramatized in “Christian” movies. You can know you’re blessed by God when everything goes well for you. Just trust God while you do A + B and, as long as you have enough faith, you should get C every time: the life you’ve always wanted. It’s a simple formula for the “blessed” life, with Jesus on top! But owning a nice house with a spacious kitchen, or driving a shiny car with no dents, or basking in financial abundance and easygoing circumstances are not reliable evidences of God’s blessing in this age. The formula might look attractive in a movie, but it contradicts both the Bible and the real-life experience of many struggling saints who are faithful in the challenges, insecurities, and pains of everyday life. Deadly Equation As I thought about what that nice lady had said about how blessed she was, Jesus spoke to me though his word: “He makes his sun rise on the evil and on the good, and sends rain on the just and on the unjust.” (Matthew 5:45) What the lady next to me said is true in a sense — she is blessed by God. But so is the greedy miser who sits in his penthouse with wealth he earned through a harsh abuse of power. Both the good lady next to me and the oppressive evil tyrant are blessed with comforts and provisions, sun and rain, houses and air conditioning every single day. God is sovereign, and he radiates goodness and pours out unearned blessings of all kinds every day. He blesses all with his common kindness. The formula God’s blessing = life comfort is a deadly one. And it’s not an isolated issue either. Unfortunately, the equation seems to be ingrained into so much American Christianity, and it’s part and parcel of the prosperity gospel that false teachers in our nation export to the world. And when I’m not careful, the plank that is the prosperity gospel protrudes from my own eye . Bruised and Blessed God’s common kindness reaches us all, but it takes saving grace to turn to Jesus when marriage is hard, when a woman — my friend — loses three babies, or when a young missionary is told he has end-stage cancer. The Bible doesn’t offer a formula, but points us to a Savior—a battered, crushed, beaten, bruised, bloodied Savior. And the special blessing of God’s presence is with those who are walking in suffering, the same road Jesus himself walked. He is present in the path of pain and trial and heartache. God was present in Joseph’s pain: Joseph’s master took him and put him into the prison, the place where the king’s prisoners were confined, and he was there in prison. But the Lord was with Joseph and showed him steadfast love and gave him favor in the sight of the keeper of the prison. (Genesis 39:20–21) God was present in David’s darkness: Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil, for you are with me; your rod and your staff, they comfort me. You prepare a table before me in the presence of my enemies; you anoint my head with oil; my cup overflows. (Psalm 23:4–5) God is present with us in today’s suffering: Beloved, do not be surprised at the fiery trial when it comes upon you to test you, as though something strange were happening to you. But rejoice insofar as you share Christ’s sufferings, that you may also rejoice and be glad when his glory is revealed. If you are insulted for the name of Christ, you are blessed, because the Spirit of glory and of God rests upon you. (1 Peter 4:12–14) So with God’s help, I remove my self-centered, American-dream plank and its sinful impulse to want a god who makes me the center and not him. My plank must come out first. And with God’s help, I toss aside the lie that we find God’s blessing in easy circumstances, or in health, or in financial prosperity. And with God’s help, I’ll keep the path, holding firmly to the hand of my Good Shepherd.