Others like the crossroads of should and must Features >>

The Power Of Thought And Visualization

The Spirit Of Leadership

The Power Of Servant-Leadership

The Power Of The Mind

The 5 Levels Of Leadership

Making Good Habits, Breaking Bad Habits

Ordering Your Private World

-160.webp)

The Fifteen Percent (Overcoming Hardships And Achieving Lasting Success)

Success Habits

Anger: Taming A Powerful Emotion

About the Book

"The Crossroads of Should and Must" by Elle Luna explores the decision between following societal expectations (should) or pursuing one's true passions and calling (must). Through personal anecdotes, inspirational stories, and practical exercises, Luna encourages readers to embrace their true selves and choose the path that aligns with their deepest desires and talents. It serves as a guide for finding fulfillment and purpose in life by following one's inner calling.

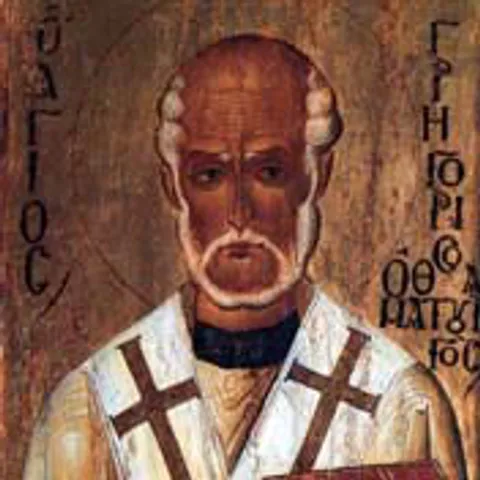

Gregory Thaumaturgus

Gregory the Wonderworker’s Early life

Gregory was born in a Pontus, a region on the southern coast of the Black Sea, located in the modern-day eastern Black Sea Region of Turkey, around 212-13. His was a wealthy home and his parents named him Theodore (Gift of God) despite their pagan beliefs. When he was 14 years old his father died and soon after, he and his brother, Athenodorus, were anxious to study law at Beirut, Lebanon, then one of the four of five famous schools in the Hellenic world.

Influence of Origen

However, on the way, they first had to escort their sister to rejoin her husband, who was a government official assigned to Caesarea in Palestine (modern Haifa, Israel). When they arrived they learned that the celebrated scholar Origen, head of the catechetical school of Alexandria, lived there.

Inquisitiveness led them to hear and speak with the Origen and his irresistible charm quickly won their hearts. They soon dropped their desires for a life in Roman law, became Christian believers and pupils of Origen, learning philosophy and theology, for somewhere between five and eight years. Origen also baptised Gregory.

Pastor (then Bishop) of Neoceasarea

Gregory returned to his native Pontus with the intention of practicing oratory, but also to write a book proving the truth of Christianity, revealing his evangelistic heart. But his plans were disrupted when locals noticed his passion for Christ and his spiritual maturity. There were just seventeen Christians in Neoceasarea when Gregory arrived and this small group persuaded him to lead them as their bishop. (‘bishop’ simply meant a local overseer). At the time, Neocaesarea was a wicked, idolatrous province.

Signs of the Spirit

By his saintly life, his direct and lively preaching, helping the needy and settling quarrels and complaints, Gregory began to see many converts to Christ. But it was the signs and wonders that particularly attracted people to Christ.

En route to Neocaesarea from Amasea, Gregory expelled demons from a pagan temple, its priest converted to Christ immediately.

Once, when he was conversing with philosophers and teachers in the city square, a notorious harlot came up to him and demanded payment for the sin he had supposedly committed with her. At first Gregory gently remonstrated with her, saying that she perhaps mistook him for someone else.

But the loose woman would not be silenced. He then asked a friend to give her the money. Just as the woman took the unjust payment, she immediately fell to the ground in a demonic fit, and the fraud became evident. Gregory prayed over her, and the devil left her. This was the beginning of Gregory’s miracles. It was at this time he became known as ‘Gregory Thaumaturgus,’ ‘Gregory the Miracle Worker’ (or Wonderworker).

At one point Gregory wanted to flee from the worldly affairs into which influential townsmen persistently sought to push him. He went into the desert, where by fasting and prayer he developed an intimacy with God and received gifts of knowledge, wisdom and prophecy. He loved life in the wilderness and wanted to remain in solitude with God until the end of his days, but the Lord willed otherwise.

His theological contribution

Though he was primarily an evangelist and pastor, Gregory also had a deep theological understanding.

His principal work ‘The Exposition of Faith’, was a theological apology for Trinitarian belief. It incorporated his doctrinal instructions to new believers, expressed his arguments against heretical groups and was widely influential amongst leaders in the Patristic period: Basil the Great, Gregory the Theologian, and Gregory of Nyssa (The Cappadocian Fathers). It was the forerunner of the Nicene Creed that was to appear in the early 4th century.

In summary

He gave himself to the task of the complete conversion of the population of his diocese. The transformation in Neocaesarea was astonishing. Persuasive preaching, numerous healings and miraculous signs had a powerful effect. Such was his success that it was said that when Gregory became bishop (c 240) he found only seventeen Christians in his diocese; when he died only seventeen remained pagan (Latourette 1953:76).

Basil the Great’s Testimony

Basil the Great (330-379, Bishop of Caesarea, in his work ‘On the Spirit’ wrote the following account of Gregory the wonder-worker.

“But where shall I rank the great Gregory, and the words uttered by him? Shall we not place among Apostles and Prophets a man who walked by the same Spirit as they; who never through all his days diverged from the footprints of the saints; who maintained, as long as he lived, the exact principles of evangelical citizenship?

I am sure that we shall do the truth a wrong if we refuse to number that soul with the people of God, shining as it did like a beacon in the Church of God: for by the fellow-working of the Spirit the power which he had over demons was tremendous, and so gifted was he with the grace of the word ‘for obedience to the faith among. . .the nations.’ that, although only seventeen Christians were handed over to him, he brought the whole people alike in town and country through knowledge to God.

He too by Christ’s mighty name commanded even rivers to change their course, and caused a lake, which afforded a ground of quarrel to some covetous brethren, to dry up. Moreover, his predictions of things to come were such as in no wise to fall short of those of the great prophets. To recount all his wonderful works in detail would be too long a task. By the superabundance of gifts, wrought in him by the Spirit, in all power and in signs and in marvels, he was styled a second Moses by the very enemies of the Church.

Thus, in all that he through grace accomplished, alike by word and deed, a light seemed ever to be shining, token of the heavenly power from the unseen which followed him. To this day he is a great object of admiration to the people of his own neighborhood, and his memory, established in the churches ever fresh and green, is not dulled by length of time. (Schaff and Wace nd., Series 2. 8:46-47).

“Gregory was a great and conspicuous lamp, illuminating the church of God.” —Basil the Great.

Gregory the Wonderworker’s Early life

Gregory was born in a Pontus, a region on the southern coast of the Black Sea, located in the modern-day eastern Black Sea Region of Turkey, around 212-13. His was a wealthy home and his parents named him Theodore (Gift of God) despite their pagan beliefs. When he was 14 years old his father died and soon after, he and his brother, Athenodorus, were anxious to study law at Beirut, Lebanon, then one of the four of five famous schools in the Hellenic world.

Influence of Origen

However, on the way, they first had to escort their sister to rejoin her husband, who was a government official assigned to Caesarea in Palestine (modern Haifa, Israel). When they arrived they learned that the celebrated scholar Origen, head of the catechetical school of Alexandria, lived there.

Inquisitiveness led them to hear and speak with the Origen and his irresistible charm quickly won their hearts. They soon dropped their desires for a life in Roman law, became Christian believers and pupils of Origen, learning philosophy and theology, for somewhere between five and eight years. Origen also baptised Gregory.

Pastor (then Bishop) of Neoceasarea

Gregory returned to his native Pontus with the intention of practicing oratory, but also to write a book proving the truth of Christianity, revealing his evangelistic heart. But his plans were disrupted when locals noticed his passion for Christ and his spiritual maturity. There were just seventeen Christians in Neoceasarea when Gregory arrived and this small group persuaded him to lead them as their bishop. (‘bishop’ simply meant a local overseer). At the time, Neocaesarea was a wicked, idolatrous province.

Signs of the Spirit

By his saintly life, his direct and lively preaching, helping the needy and settling quarrels and complaints, Gregory began to see many converts to Christ. But it was the signs and wonders that particularly attracted people to Christ.

En route to Neocaesarea from Amasea, Gregory expelled demons from a pagan temple, its priest converted to Christ immediately.

Once, when he was conversing with philosophers and teachers in the city square, a notorious harlot came up to him and demanded payment for the sin he had supposedly committed with her. At first Gregory gently remonstrated with her, saying that she perhaps mistook him for someone else.

But the loose woman would not be silenced. He then asked a friend to give her the money. Just as the woman took the unjust payment, she immediately fell to the ground in a demonic fit, and the fraud became evident. Gregory prayed over her, and the devil left her. This was the beginning of Gregory’s miracles. It was at this time he became known as ‘Gregory Thaumaturgus,’ ‘Gregory the Miracle Worker’ (or Wonderworker).

At one point Gregory wanted to flee from the worldly affairs into which influential townsmen persistently sought to push him. He went into the desert, where by fasting and prayer he developed an intimacy with God and received gifts of knowledge, wisdom and prophecy. He loved life in the wilderness and wanted to remain in solitude with God until the end of his days, but the Lord willed otherwise.

His theological contribution

Though he was primarily an evangelist and pastor, Gregory also had a deep theological understanding.

His principal work ‘The Exposition of Faith’, was a theological apology for Trinitarian belief. It incorporated his doctrinal instructions to new believers, expressed his arguments against heretical groups and was widely influential amongst leaders in the Patristic period: Basil the Great, Gregory the Theologian, and Gregory of Nyssa (The Cappadocian Fathers). It was the forerunner of the Nicene Creed that was to appear in the early 4th century.

In summary

He gave himself to the task of the complete conversion of the population of his diocese. The transformation in Neocaesarea was astonishing. Persuasive preaching, numerous healings and miraculous signs had a powerful effect. Such was his success that it was said that when Gregory became bishop (c 240) he found only seventeen Christians in his diocese; when he died only seventeen remained pagan (Latourette 1953:76).

Basil the Great’s Testimony

Basil the Great (330-379, Bishop of Caesarea, in his work ‘On the Spirit’ wrote the following account of Gregory the wonder-worker.

“But where shall I rank the great Gregory, and the words uttered by him? Shall we not place among Apostles and Prophets a man who walked by the same Spirit as they; who never through all his days diverged from the footprints of the saints; who maintained, as long as he lived, the exact principles of evangelical citizenship?

I am sure that we shall do the truth a wrong if we refuse to number that soul with the people of God, shining as it did like a beacon in the Church of God: for by the fellow-working of the Spirit the power which he had over demons was tremendous, and so gifted was he with the grace of the word ‘for obedience to the faith among. . .the nations.’ that, although only seventeen Christians were handed over to him, he brought the whole people alike in town and country through knowledge to God.

He too by Christ’s mighty name commanded even rivers to change their course, and caused a lake, which afforded a ground of quarrel to some covetous brethren, to dry up. Moreover, his predictions of things to come were such as in no wise to fall short of those of the great prophets. To recount all his wonderful works in detail would be too long a task. By the superabundance of gifts, wrought in him by the Spirit, in all power and in signs and in marvels, he was styled a second Moses by the very enemies of the Church.

Thus, in all that he through grace accomplished, alike by word and deed, a light seemed ever to be shining, token of the heavenly power from the unseen which followed him. To this day he is a great object of admiration to the people of his own neighborhood, and his memory, established in the churches ever fresh and green, is not dulled by length of time. (Schaff and Wace nd., Series 2. 8:46-47).

“Gregory was a great and conspicuous lamp, illuminating the church of God.” —Basil the Great.

A Lesson for All from Newtown

Murdering a human being is an assault on God. He made us in his own image. Destroying an image usually means you hate the imaged. Murdering God’s human image-bearer is not just murder. It’s treason — treason against the creator of the world. It is a capital crime — and more. “Whoever sheds the blood of man, by man shall his blood be shed, for God made man in his own image” (Genesis 9:6). As usual, Jesus takes this up in devastating terms. None of us escapes. You have heard that it was said to those of old, “You shall not murder; and whoever murders will be liable to judgment.” But I say to you that everyone who is angry with his brother will be liable to judgment; whoever insults his brother will be liable to the council; and whoever says, “You fool!” will be liable to the hell of fire. (Matthew 5:21–22) He does not say unwarranted anger is the same as murder. It’s not. Ask the bereaved parents of Newtown. He says both are liable to hell. Both come under a similar sentence from God. Why would Jesus say that? Because both are a sin against God, not just man. Jesus’s threat of hell is owing not to the seriousness of murder against man, but to the seriousness of treason against God. In the mind of Jesus — the mind of God — heartfelt verbal invective against God’s image is an assault on the infinite dignity of God, the infinite worth of God. It is, therefore, in Jesus’s mind, worthy of God’s righteous judgment. So what we saw yesterday in the Newtown murders was a picture of the seriousness of our own corruption. None of us escapes the charge of sinful anger and verbal venom. So we are all under the just sentence of God’s penalty. That is what Jesus was saying in Matthew 5:21–22. And it is exactly what Jesus said again when people pressed him to talk about the time Pilate slaughtered worshippers in the temple. Instead of focusing on the slain or the slayer, he focused on all of us: Do you think that these Galileans were worse sinners than all the other Galileans, because they suffered in this way? No, I tell you; but unless you repent, you will all likewise perish. (Luke 13:2–3) Which means that the murders of Newtown are a warning to me — and you. Not a warning to see our schools as defenseless, but to see our souls as depraved. To see our need for a Savior. To humble ourselves in repentance for the God-diminishing bitterness of our hearts. To turn to Christ in desperate need, and to treasure his forgiveness, his transforming, and his friendship. Article by John Piper