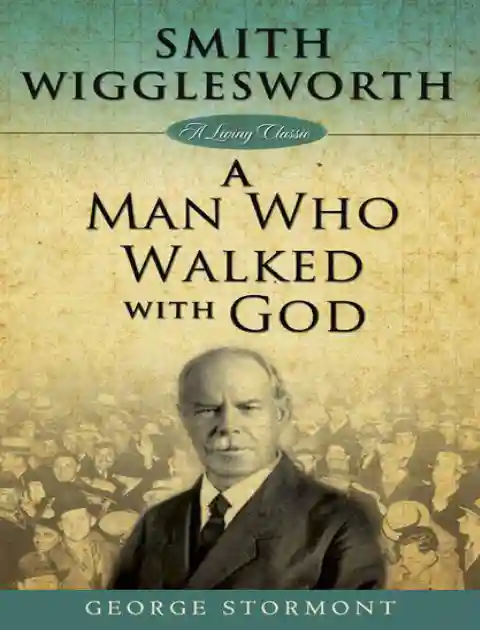

Smith Wigglesworth: A Man Who Walked With God Order Printed Copy

- Author: George Stormont

- Size: 1.3MB | 205 pages

- |

Others like smith wigglesworth: a man who walked with god Features >>

Smith Wigglesworth : A Life Ablaze With The Power Of God

Smith Wigglesworth: Apostle Of Faith

Elijah .. The Man Who Did Not Die

-160.webp)

God's Generals (Smith Wigglesworth)

God's Generals - The Missionaries

God's Generals: Jack Coe

William Branham: A Man Sent By God

The Great Life Of St Benedict

Charlie Coulson: The Christian Drummer Boy

Testimonies To The Church, Vol 1

About the Book

"Smith Wigglesworth: A Man Who Walked With God" by George Stormont provides a detailed account of the life and ministry of Smith Wigglesworth, a prominent figure in the Pentecostal and Charismatic movements. The book highlights Wigglesworth's deep faith, powerful healing ministry, and intimate relationship with God, offering inspiration for readers seeking to deepen their own spiritual lives.

Manny Mill

Too Afraid to Say Nothing

On a steamy Saturday in July, I dropped off our son at a local community college to take the ACT. Earlier that morning, before leaving the house, we paused for prayer. I knew how nervous he was, how much he hates a timed test. I remembered my own anxiety and apprehension as a high schooler, realizing that part of your future rests on a few hours in a room full of strangers. So, I prayed for him not to be afraid. Fear is a curious and powerful emotion. It can debilitate. Fear can stop our mind, shut our mouth, and stay our hand. Yet fear can also set us into action. As much as fear keeps us from taking risks and being effective, fear can also be an incredible motivator. In a way, fear is what’s made our son an excellent student thus far. It’s what kept him up studying late at night, and it’s why he willingly walked into that testing room. The right kind of fear is also one of the best motivators for our evangelism. Fear That Freezes Evangelism When it comes to evangelism, Christians tend to view fear as purely negative. Many of us have come to believe that fear is the primary factor that keeps us from speaking the gospel to others. Fear freezes us. When we sense the Spirit leading us to talk with our neighbor, friend, or family member, we get the same feeling that many of us experienced on a Friday algebra exam. We struggle to focus. Our hands perspire. We don’t even know where to begin. Some of that physical response comes from a fear of failure. Like when taking a test, we don’t want to mess up. We don’t want to give someone the wrong answer. So, churches often respond by providing evangelism training. Education is the solution. We help people prepare, supply them with resources, and even give them, as it were, the opportunity for practice tests. And this information is truly important. We must be able to proclaim the gospel clearly and truthfully. Such an approach in evangelism training, however, might assume that the way we address fear in evangelism is primarily through increasing our accuracy and ability. But I’m not convinced, because I believe the fear that freezes us would more accurately be labeled as shame (Luke 12:8–9; 2 Timothy 1:8–12). The Fear of Rejection I suspect the greatest hindrance to bold witness is not the fear of getting it wrong; it’s the fear of being rejected. We don’t want to be ostracized or shunned. We don’t want our friends to think we’re narrow-minded, unscientific, bigoted, intolerant, or just uncool. If we’re honest, we’re often too embarrassed to evangelize. We’re ashamed of Christ. Education will never overcome that kind of fear. Instead, we need to encourage bold witness by dealing with the emotional and social dynamics of shame. Shame’s power is its ability to disgrace and divide. Shame humiliates and separates from others. Which means the antidote to shame is glory and community — and we find those in the gospel. The good news of Jesus promises us both honor and a home (Matthew 10:32; John 14:1–3). Only when Christians recognize this will they be able to overcome the shame that silences their witness. Because they’ll be more confident in the praise and glory that God himself promises them on the final day (1 Peter 1:7; Romans 2:7). They’ll fear rejection less, because they’ll have experienced the welcome of Christian fellowship, the earthly foretaste of the heavenly home that God gives his chosen exiles. Fear That Fuels Evangelism Realizing the social and emotional dynamics of fear can also help us see how it can be a positive motivator for mission. In recent years, there’s been such an experiential increase in a particular kind of fear that the phenomenon has been given a pop-culture label: FOMO — the fear of missing out. FOMO is understood as people’s anxiety, largely fueled by viewing social media, that they’ll miss out on some exciting event, important relationship, or salacious news. But this particular fear doesn’t generally stifle people. It drives them to constantly check their phones. It leads them to follow more people, make more friends, be more active. Now, I’m not suggesting that FOMO leads to positive or healthy behavior. What is helpful to see, though, is how fear can powerfully move us into action. If we experience a fear similar to FOMO with regard to evangelism, we can see how it could lead us to pursue our neighbors and open our mouths with the gospel. Once we have tasted of God’s goodness in the gospel, we will want others to experience the same. We will fear them missing out on the glories of heaven, the wonders of Christ, and the most spectacular news of all. Such fear is not antithetical to love; it’s a demonstration of Christ’s compassion for them (2 Corinthians 5:14). But there’s more to understanding how fear should fuel our evangelism. Jesus said, “Whoever is ashamed of me and of my words, of him will the Son of Man be ashamed when he comes in his glory and the glory of the Father and of the holy angels” (Luke 9:26). There it is. The solution to the shame that silences our witness is our fear of missing out on glory and honor with the heavenly host. If we are embarrassed of Christ and his gospel, if we avoid evangelism as a way to protect our reputation and maintain our relationships, we will lose the honor he promises. We will miss out on the community of glory, with the Father and all his holy angels. More Fear, Not Less This means that fear is not the greatest hindrance to evangelism. Our lack of fear is. Instead of being ashamed before others, we need to be concerned about being ashamed before Christ at his coming (1 John 2:28). Instead of fearing what others will say about us or do to us, we need to fear God, the one “who can destroy both soul and body in hell” (Matthew 10:28). Shame isn’t purely negative. “Knowing the fear of the Lord, we persuade others” (2 Corinthians 5:11). Fear can be a positive force. My son realized that taking the ACT is the means to college admission, a potential scholarship, and a future career. The results also have a profound emotional and social dimension — just wait until the scores come back! He knows the stakes are high. But recognizing the weight can be a motivating factor, and not necessarily a debilitating one. So it can be for us. As we grow in an appropriate fear of God and for others’ eternal well-being, we will be moved to speak the gospel with more urgency and care. And as we sense the honor and home that God promises us in Christ, we will fear less the humiliation and rejection of others. We will not be ashamed of the gospel. Article by Elliot Clark