Inspiring, I was much impacted. The book made me understand that I am God's workmanship, and all I need to do is to depend on Christ to live for Christ and to wage war with Christ. This review has also helped me to remember what I read. I will read the Book of Ephesians again this weekend. What an exposition.

- ngwoke ifeanyi (8 months ago)

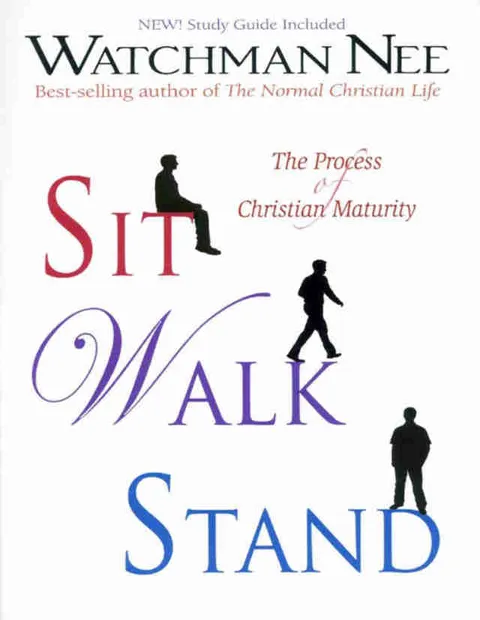

About the Book

"Sit, Walk, Stand" by Watchman Nee is a concise and powerful Christian book that explores the themes of spiritual growth and maturity. Nee uses the three words in the title as a framework to discuss the believer's position in Christ (sit), the believer's walk in the world (walk), and the believer's victory over spiritual warfare (stand). The book encourages readers to fully grasp their identity in Christ, live a life of obedience and faith, and rely on God's strength to overcome challenges. It is a practical and insightful guide for Christians seeking to deepen their relationship with God and live out their faith in a more meaningful way.

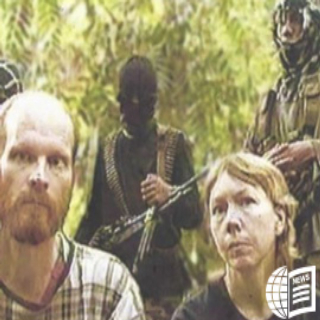

Martin and Gracia Burnham

Martin Burnham and Gracia were missionaries who served for 17 years in the Philippines. After their marriage, they underwent hard training in the jungle to prepare themselves to serve in jungle parts. Martin, being a pilot missionary, supported other missionaries who were working among the tribals in jungles. He delivered groceries and medicines to missionaries and tribals and transported sick people to medical facilities. He always had a big heart for tribals and missionaries. Gracia supported him well in the work.

On May 29, 2001, while relaxing at a resort after Martin’s one overseas mission, a Muslim militant group called the Abu Sayyaf Group attacked the resort and abducted the missionary couple and few others for ransom. The missionaries were kept captive for more than a year.

During that one year, the couple went through terrible experiences. They suffered starvation, sleeplessness and sickness, witnessed atrocities of militants and experienced gun battles between militants and the military. Amidst suffering, God was their only hope and strength.

At some point, Gracia was so depressed that although she believed that Christ died for her, she felt God doesn’t love her anymore. Martin said to her “either you believe it all or don’t believe it at all.” They encouraged one another to stand firm in the faith.

Martin Burnham and Gracia ministry in Philippines

Finally, on June 7, 2002, in a rescue operation by the Philippine military, wounded Gracia was rescued. But 42 years old Martin died in the gunfight during the rescue. Later, Gracia went back to America and joined her children.

Gracia did not let her painful experiences depress her and move her away from God. But she used those experiences to encourage others who are going through hardships. She founded the Martin and Gracia Burnham Foundation, which supports missionary aviation and tribal mission work around the world. It also focuses on ministries among Muslims. She forgave who abducted them, visited them in jail and shared Christ’s love. Some of them accepted Christ. Gracia believes that this may be God’s great purpose behind their suffering.

Martin Burnham and Gracia were missionaries who served for 17 years in the Philippines. After their marriage, they underwent hard training in the jungle to prepare themselves to serve in jungle parts. Martin, being a pilot missionary, supported other missionaries who were working among the tribals in jungles. He delivered groceries and medicines to missionaries and tribals and transported sick people to medical facilities. He always had a big heart for tribals and missionaries. Gracia supported him well in the work.

On May 29, 2001, while relaxing at a resort after Martin’s one overseas mission, a Muslim militant group called the Abu Sayyaf Group attacked the resort and abducted the missionary couple and few others for ransom. The missionaries were kept captive for more than a year.

During that one year, the couple went through terrible experiences. They suffered starvation, sleeplessness and sickness, witnessed atrocities of militants and experienced gun battles between militants and the military. Amidst suffering, God was their only hope and strength.

At some point, Gracia was so depressed that although she believed that Christ died for her, she felt God doesn’t love her anymore. Martin said to her “either you believe it all or don’t believe it at all.” They encouraged one another to stand firm in the faith.

Martin Burnham and Gracia ministry in Philippines

Finally, on June 7, 2002, in a rescue operation by the Philippine military, wounded Gracia was rescued. But 42 years old Martin died in the gunfight during the rescue. Later, Gracia went back to America and joined her children.

Gracia did not let her painful experiences depress her and move her away from God. But she used those experiences to encourage others who are going through hardships. She founded the Martin and Gracia Burnham Foundation, which supports missionary aviation and tribal mission work around the world. It also focuses on ministries among Muslims. She forgave who abducted them, visited them in jail and shared Christ’s love. Some of them accepted Christ. Gracia believes that this may be God’s great purpose behind their suffering.

The Difficult Habit of Quiet

The habit of quiet may be harder today than ever before. Don’t get me wrong: it’s always been hard. The rise and spread of technology, however, tends to crowd out quiet even more. Now that we can carry the whole wide and wild world in our pockets, it’s that much harder to keep the world at bay. Our phones always promise another update to see, image to like, website to visit, game to play, text to read, stream to watch, forecast to monitor, podcast to download, headline to scan, article to skim, score to check, price to compare. That kind of access, and semblance of control, can begin to make quiet moments feel like wasted ones. Who could sit and be still while so much life rushes by? Even if we don’t immediately pick up our phones, we’re often still held captive by them, wondering what new they might hold — what we might be missing. As hard as quiet might be to come by, however, it’s still a life-saving, soul-strengthening habit for any human soul. The God who made this wide and wild world, and who molded our finite and fragile frames, says of us, “In quietness and in trust shall be your strength” (Isaiah 30:15). In days filled with noise, do you still find time to be this kind of strong? Or has stress and distraction slowly eroded your spiritual health? How often do you stop to be quiet? What God Does with Quiet What kind of quietness produces strength? Not all quietness does. We could sell our televisions, give away our phones, move to the countryside, and still be as weak as ever. No, “in quietness and in trust shall be your strength.” The quiet we need is a quiet filled with God. Quietness becomes strength only when our stillness says that we need him. Be still, and know that I am God. I will be exalted among the nations, I will be exalted in the earth! (Psalm 46:10) This still, trusting quietness defies self-reliance. Quietness can preach reality to our souls like few habits can. It says that he is God, and we are not; he knows all, and we know little; he is strong, and we are weak. Quietness widens our eyes to the bigness of God and the smallness of us. It brings us low enough to see how high and wise and worthy he is. You can begin to see why quietness can be so hard. It’s deeply (sometimes ruthlessly) humbling. For it to say something true and beautiful about God, it first says something true and devastating about us. Our quietness says, “Without him, you can do nothing.” Our refusal to be quiet, on the other hand, says, “I can do a whole lot on my own” — and that feels good to hear. It just robs us of the real strength and help we might have found. God strengthens the quiet with his strength, because quietness turns weakness and neediness into worship (2 Corinthians 12:9–10). We get the strength and help and joy; he gets the glory. But You Were Unwilling The context of Isaiah’s words, however, is not inspiring, but sobering. God says to his people, “In returning and rest you shall be saved; in quietness and in trust shall be your strength.” But you were unwilling . . . (Isaiah 30:15–16) Quietness would have made them strong, but they wouldn’t have it. Assyria was bearing down on Judah, threatening to crush them as it had crushed many before them. And how do God’s people respond? “Ah, stubborn children,” declares the Lord, “who carry out a plan, but not mine, and who make an alliance, but not of my Spirit, that they may add sin to sin; who set out to go down to Egypt, without asking for my direction.” (Isaiah 30:1–2) Even after watching him deliver them so many times before, they cast his plan aside and made their own. They sought help, but not from him. They went back to Egypt (of all places!) and asked those who had enslaved and oppressed them to protect them. And they didn’t even stop to ask what God thought. They did, and did, and did, at every turn refusing to stop, be quiet, and receive the strength and support of God. I would rush to help you, God says, but you were unwilling. You weren’t patient or humble enough to receive my help. “How often do we choose activity over quietness, distraction over meditation, ‘productivity’ over prayer?” Why would they refuse the sovereign help of God? Deep down, we know why. Because they felt safer doing what they could do on their own than they did waiting to see what God might do. How often do we do the same? How often do we choose activity over quietness, distraction over meditation, “productivity” over prayer? How often do we try to solve our problems without slowing down enough to first seek God? Consequences of Avoiding Quiet Self-reliance is, of course, not as productive as it promises to be — at least not in the ways we would want. The people’s refusal to be quiet and ask God for help not only cut them off from his strength, but also invited other painful consequences. First, the sin of self-reliance breeds more sin. Again, God says in verse 1, “‘Ah, stubborn children,’ declares the Lord, ‘who carry out a plan, but not mine, and who make an alliance, but not of my Spirit, that they may add sin to sin.” The more we refuse the strength of God, the more we invite temptations to sin. Quiet keeps us close to God and aware of him. A scarcity of quiet pushes him to the margins of our hearts, making room for Satan to plant and tend lies within us. Second, their refusal to be quiet before God made them vulnerable to irrational fear. Because they fought in their own strength, the Lord says, “A thousand shall flee at the threat of one; at the threat of five you shall flee” (Isaiah 30:17). A lone soldier will send a thousand into a panic. The whole nation will crumble and surrender to just five men. In other words, you will be controlled and oppressed by irrational fears. You’ll run away when no one’s chasing you. You’ll lose sleep when there’s nothing to worry about. And right when you’re about to experience a breakthrough, you’ll despair and give up. Fears swell and flourish as long as God remains small and peripheral. Quiet time with God, however, scatters those fears by enlarging and inflaming our thoughts of him. The weightiest warning, however, comes in verse 13: those who forsake God’s word, God’s help, God’s way invite sudden ruin. “This iniquity shall be to you like a breach in a high wall, bulging out and about to collapse, whose breaking comes suddenly, in an instant.” Confidence in self drove a crack in the strongholds around them — a crack that grew and spread until the walls collapsed on top of them. All because they refused to embrace quiet and trust God. “In quietness and trust would be our strength; in busyness and pride will be our downfall.” For Judah, ruin meant falling into the cruel hands of the Assyrians. The walls will fall differently for us, but fall they will, if we let busyness and noise keep us from dependence. In quietness and trust would be our strength; in busyness and pride will be our downfall. Mercy for the Self-Reliant In the rhythms of our lives, do we make time to be quiet before God? Do we expect God to do more for us while we sit and pray than we can do by pushing through without him? If verse 15 humbles us — “But you were unwilling . . .” — verse 18 should humble us all the more. As Judah hurries and worries and strategizes and plans and recruits help and works overtime, all the while avoiding God, how does God respond to them? What is he doing while they refuse to stop doing and be quiet? Therefore the Lord waits to be gracious to you, and therefore he exalts himself to show mercy to you. For the Lord is a God of justice; blessed are all those who wait for him. (Isaiah 30:18) While we refuse to wait for him, God waits to be gracious to us. He’s not watching to see if he’ll be forced to show us mercy; he wants to show us mercy. The God of heaven, the one before time, above time, and beyond time, waits for us to ask for help. He loves to hear the sound of quiet trust. Blessed — happy — are those who wait for him, who know their need for him, who ask him for help, who find their strength in his strength, who learn to be and stay quiet before him. Article by Marshall Segal

-160.webp)