About the Book

"Revival Fire" by Wesley D. is a book that explores the concept of spiritual revival and awakening in the Christian faith. The author discusses the importance of seeking a personal relationship with God, experiencing transformation through the Holy Spirit, and embracing a lifestyle of prayer and worship. Through powerful stories and insights, the book inspires readers to pursue a deeper connection with God and ignite a revival in their own lives.

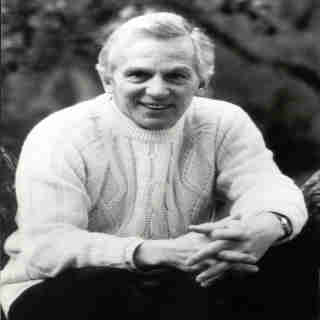

Brother Andrew

Son of a blacksmith, Brother Andrew didn’t even finish high school. But God used this ordinary dutch man, with his bad back, limited education, without sponsorship and no funds to do things that many said were impossible. From Yugoslavia to North Korea, Brother Andrew penetrated countries hostile to the gospel to bring bibles and encouragement to believers.

Andy van der Bijl, who became known as Brother Andrew, was born in 1928 the son of a deaf father and a semi-invalid mother. Andrew was the third of six children and they lived in the smallest house in the village of Witte in the Netherlands.

In the book God’s smuggler, Andrew describes the impact that the death of his oldest brother ‘Bas’ had upon him. Bas, who was severely handicapped died when Andrew was just 11 years old. Andrew had wanted to die with Bas, but God hadn’t let him.

THIRST FOR ADVENTURE

As a child, brother Andrew was mischievous and dreamt of adventure. When Germany invaded, Andrew amused himself (and the rest of the village) by playing pranks on the occupying troops.

NOTORIOUS COMMANDO WHO NEEDED GOD

His thirst for adventure led him into the Dutch army at the age of 18 where he became a notorious commando. Andrew and his comrades became famous for wearing yellow straw hats in battle, their motto was: ‘get smart – lose your mind’.

The atrocities that Andrew committed as a commando haunted him and he became wrapped in a sense of guilt. Nothing he did – drinking, fighting, writing or reading letters helped him escape the strangle that guilt had upon him.

Shot in the ankle in combat, at the age of 20, his time in the army came to an abrupt end.

In hospital, bed ridden, the witness of Franciscan sisters who served the sick joyfully and the conviction of his own sin, drove him to read the Bible. Andy studied the bible while asking many questions to a friend (Thile), who had written to him throughout his time in the army. Andrew sent questions to Thile who searched for answers from her pastor and the library. His searching within the bible did not however lead him to give his life to God whilst he was still in hospital.

ANDREW RETURNS HOME A CRIPPLE AND SEEKS GOD

Returning home a cripple to his old town, Andrew’s life was empty. He had not found the adventure he had been looking for.

Somehow however, when he return home, he developed a thirst for God. Every evening Andrew attended a meeting and during the day he would read the bible and lookup up bible verses mentioned in the sermons he had heard. At last, one evening he gave up his ego and prayed: ‘Lord if You will show me the way, I will follow You. Amen’.

GOD CALLS BROTHER ANDREW TO MISSION

Soon after becoming a Christian, Brother Andrew attended a an evangelistic meeting taken by a Dutch evangelist Arne Donker. At this meeting Andrew responded to the call to become a missionary. This call to share the good news of salvation started at home, with Andrew and his friend Kees holding an evangelistic event with Pastor Donker in their home town of Witte.

Before going away on mission, Andrew started work at the Ringers chocolate factory. Working in a female dominated environment which was smitten with filthy jokes, God used Andrew and another Christian, and future wife Corrie, to reach their lost co-workers. Through personal witness and inviting them to evangelistic events, many became Christians, including the ring leader of the women. The atmosphere at work changed dramatically and prayer groups were held.

Andrew excelled in his work despite being lame and Mr Ringers, the owner of the factory applauded his work and evangelistic efforts. Because of his high IQ, Andrew was trained up as a job analyst within the factory. But Andrew knew that God was calling him to mission. The big obstacle however was his lack of education.

Giving up smoking, Andrew was able to start saving to buy books. Andrew bought dictionaries and commentaries and so began studying in his spare time. One day Andrew learnt about the bible college in Glasgow run by the WEC mission. At Glasgow bible college Christians could be trained up for mission in 2 years.

Unsure of Gods will for his life, Andrew spent a Sunday afternoon alone with God, speaking aloud with God. Through this time, Andrew realised that he needed to say ‘yes’ to God who was calling him to mission. Before this, Andrew had been saying ‘Yes BUT I am lame.’ ‘Yes BUT I have no education’. Andrew said yes. In an amazing instant, Andrew made this step of yes, and in God’s grace he healed Andrews lame leg.

ANDREW GOES TO ENGLAND

Andrew applied for the Bible college in Glasgow and was accepted. Sponsored by no church, no organisation and lacking education, Andrew obeyed God and went despite being told by the love of his life at the time (Thile) that in going he would lose her.

Andrew’s place at the bible college was delayed by a year. Despite receiving a telegram from WEC telling him not to come, Andrew believed God was instructing him to go. In faith he obeyed God and left for England in 1952.

Andrew spent the first few months in England painting the WEC headquarters building (Bulstrode). While living at Bulstrode, Andrew began spending time with God at the beginning of everyday – a Quiet Time. This was something that Andrew found helpful and endeavoured to do every day of his life. Once Andrew had finished painting Bulstrode, he then moved in with Mr and Mrs Hopkins. Living with Mr and Mrs Hopkins, they developed a wonderful relationship. Andy learnt so much from the couple because they were utterly without self-consciousness and opened up their home to drunks and beggars.

In September 1953, Brother Andrew started his studies at the WEC Glasgow bible college. Over the entrance of the wooden archway of the college were the words‘have faith in God’. During the following two years whilst studying, Andrew learnt about having faith in God and put his faith into practice in numerous ways.

THE KINGS WAY

Throughout his time at Glasgow bible college, Andy learnt of ‘The Kings Way’ in providing. Andrew saw God provide every essential need he had and always provide on time. In the book God’s Smuggler, Andrew describes how it was exciting waiting to see how God would provide at his time of need. God always provided, but did so, not according to mans logic but in a kingly matter, not in a grovelling way.

One example of God providing miraculously was when Andrew needed to pay his visa. When Andrew received a visitor the day before he needed to send off his application for a visa, he was confident that the visitor would have come to give him money to pay for the visa. But the visitor was Richard, a man who Andrew had met in the slums in Glasgow. Richard had not come to give, but to ask. Andy explained that he had no money himself to give to Richard, but as he spoke, Andy saw a Shilling on the floor. This shilling was how much Andy needed to pay for his visa which would mean he could stay at the bible school. Rather than keeping the Shilling for himself, Andrew gave the Shilling to Richard. Andy had done what he knew was right, but how would God provide? Minutes later, Andy received a letter and in it was 30 Shillings! God had provided in His way, a Kingly Manner of provision.

GOD CALLS ANDREW BEHIND THE IRON CURTAIN

Leaving bible college in 1955, God guided Andy to attend a Communist trip to Warsaw. This would be the first of many trips into Communist countries.

During his first trip to Warsaw, brother Andrew visited local churches, a bible shop and spoke with Christians in the country. Coming back to Holland, Andrew had lots of opportunities to share about his trip and how Christians lived behind the iron curtain.

Weeks later, the communist party arranged for him to attend a trip to Czechoslovakia. Andrew managed to break away from the organised trip to learn that the church was suffering and that bibles were very scarce. Officials were angry he had broken away from the official tour and had contact with Christians so he was prohibited from entering the country again. But his trip had opened his eyes to the needs of the church behind the iron curtain and this became his mission field.

In the following years, Andy dedicated his life to the needs of the church in the Communist countries. God provided Andrew with a new Volkswagen Beetle and with it Brother Andrew smuggled bibles and literature into the countries in need. Working alone for the first few years, Andrew worked tirelessly in serving the churches behind the iron curtain. When Andrew had finished one trip he would go back to Holland where he would share his experience and then go back to one of the countries. Each trip was full of stories of how God had miraculously provided and led Andrew to meet Godly believers.

ANDREW MARRIES AND HAS A FAMILY

Although serving God in this way was exciting, Andrew felt alone and wanted a wife. In the book God’s Smuggler, Andrew describes how he prayed about a wife three times. The first two times that Brother Andrew asked for a wife God spoke to him clearly through Isaiah 54:1 “The children of the desolate are more than the children of the married”. But Andrew prayed a third time about it, and this time God answered his prayer, reminding him of a lady he worked with at the Ringers chocolate factor, Corrie van Dam. Andrew hadn’t had contact with Corrie for a long time so went to visit her. By God’s grace, Corrie was still single and over a period of several years Andrew and Corrie became great friends. Corrie and Andrew married on June 27th 1958 in Alkmaar, Netherlands.

Corrie was married to a missionary and Andrew very much continued to live like a missionary, smuggling bibles into countries closed countries. Over the years, God blessed Corrie and Andrew with five children, three boys and two girls.

ANDREW STARTS WORKING WITH OTHERS

Andrew kept serving God behind the iron curtain but the work had become difficult to do alone. Andrew thought about how helpful it would be to have a co-worker. This began with a man called Hans and slowly grew until a number of them were smuggling bibles into the communist countries.

SERVING THE WORLD WIDE CHURCH

When the doors to communist Europe were opened in the 1960’s, Brother Andrew began to serve and strengthen the churches in the Middle East and Islamic world.

BROTHER ANDREW RECEIVES RELIGIOUS LIBERTY AWARD IN 2007

On Andy van der Bijl’s 69th birthday, he was honoured by being awarded ‘The Religious Liberty Award’ which was presented by the World Evangelical Fellowship (WEF). The chairman of WEF’s Religious Liberty Commission stated:

“Brother Andrew has been the preeminent example of those from the outside who have excelled in the ministry of encouragement – the many years he has devoted himself to serving the oppressed. His exploits have become legendary as he has crossed borders carrying Bibles, which were liable to confiscation. Time after time God has blinded the eyes of the border guards, and the Bibles got through.

BROTHER ANDREW RESOURCES

God’s Smuggler – Book about Brother Andrew smuggling Bibles.

Son of a blacksmith, Brother Andrew didn’t even finish high school. But God used this ordinary dutch man, with his bad back, limited education, without sponsorship and no funds to do things that many said were impossible. From Yugoslavia to North Korea, Brother Andrew penetrated countries hostile to the gospel to bring bibles and encouragement to believers.

Andy van der Bijl, who became known as Brother Andrew, was born in 1928 the son of a deaf father and a semi-invalid mother. Andrew was the third of six children and they lived in the smallest house in the village of Witte in the Netherlands.

In the book God’s smuggler, Andrew describes the impact that the death of his oldest brother ‘Bas’ had upon him. Bas, who was severely handicapped died when Andrew was just 11 years old. Andrew had wanted to die with Bas, but God hadn’t let him.

THIRST FOR ADVENTURE

As a child, brother Andrew was mischievous and dreamt of adventure. When Germany invaded, Andrew amused himself (and the rest of the village) by playing pranks on the occupying troops.

NOTORIOUS COMMANDO WHO NEEDED GOD

His thirst for adventure led him into the Dutch army at the age of 18 where he became a notorious commando. Andrew and his comrades became famous for wearing yellow straw hats in battle, their motto was: ‘get smart – lose your mind’.

The atrocities that Andrew committed as a commando haunted him and he became wrapped in a sense of guilt. Nothing he did – drinking, fighting, writing or reading letters helped him escape the strangle that guilt had upon him.

Shot in the ankle in combat, at the age of 20, his time in the army came to an abrupt end.

In hospital, bed ridden, the witness of Franciscan sisters who served the sick joyfully and the conviction of his own sin, drove him to read the Bible. Andy studied the bible while asking many questions to a friend (Thile), who had written to him throughout his time in the army. Andrew sent questions to Thile who searched for answers from her pastor and the library. His searching within the bible did not however lead him to give his life to God whilst he was still in hospital.

ANDREW RETURNS HOME A CRIPPLE AND SEEKS GOD

Returning home a cripple to his old town, Andrew’s life was empty. He had not found the adventure he had been looking for.

Somehow however, when he return home, he developed a thirst for God. Every evening Andrew attended a meeting and during the day he would read the bible and lookup up bible verses mentioned in the sermons he had heard. At last, one evening he gave up his ego and prayed: ‘Lord if You will show me the way, I will follow You. Amen’.

GOD CALLS BROTHER ANDREW TO MISSION

Soon after becoming a Christian, Brother Andrew attended a an evangelistic meeting taken by a Dutch evangelist Arne Donker. At this meeting Andrew responded to the call to become a missionary. This call to share the good news of salvation started at home, with Andrew and his friend Kees holding an evangelistic event with Pastor Donker in their home town of Witte.

Before going away on mission, Andrew started work at the Ringers chocolate factory. Working in a female dominated environment which was smitten with filthy jokes, God used Andrew and another Christian, and future wife Corrie, to reach their lost co-workers. Through personal witness and inviting them to evangelistic events, many became Christians, including the ring leader of the women. The atmosphere at work changed dramatically and prayer groups were held.

Andrew excelled in his work despite being lame and Mr Ringers, the owner of the factory applauded his work and evangelistic efforts. Because of his high IQ, Andrew was trained up as a job analyst within the factory. But Andrew knew that God was calling him to mission. The big obstacle however was his lack of education.

Giving up smoking, Andrew was able to start saving to buy books. Andrew bought dictionaries and commentaries and so began studying in his spare time. One day Andrew learnt about the bible college in Glasgow run by the WEC mission. At Glasgow bible college Christians could be trained up for mission in 2 years.

Unsure of Gods will for his life, Andrew spent a Sunday afternoon alone with God, speaking aloud with God. Through this time, Andrew realised that he needed to say ‘yes’ to God who was calling him to mission. Before this, Andrew had been saying ‘Yes BUT I am lame.’ ‘Yes BUT I have no education’. Andrew said yes. In an amazing instant, Andrew made this step of yes, and in God’s grace he healed Andrews lame leg.

ANDREW GOES TO ENGLAND

Andrew applied for the Bible college in Glasgow and was accepted. Sponsored by no church, no organisation and lacking education, Andrew obeyed God and went despite being told by the love of his life at the time (Thile) that in going he would lose her.

Andrew’s place at the bible college was delayed by a year. Despite receiving a telegram from WEC telling him not to come, Andrew believed God was instructing him to go. In faith he obeyed God and left for England in 1952.

Andrew spent the first few months in England painting the WEC headquarters building (Bulstrode). While living at Bulstrode, Andrew began spending time with God at the beginning of everyday – a Quiet Time. This was something that Andrew found helpful and endeavoured to do every day of his life. Once Andrew had finished painting Bulstrode, he then moved in with Mr and Mrs Hopkins. Living with Mr and Mrs Hopkins, they developed a wonderful relationship. Andy learnt so much from the couple because they were utterly without self-consciousness and opened up their home to drunks and beggars.

In September 1953, Brother Andrew started his studies at the WEC Glasgow bible college. Over the entrance of the wooden archway of the college were the words‘have faith in God’. During the following two years whilst studying, Andrew learnt about having faith in God and put his faith into practice in numerous ways.

THE KINGS WAY

Throughout his time at Glasgow bible college, Andy learnt of ‘The Kings Way’ in providing. Andrew saw God provide every essential need he had and always provide on time. In the book God’s Smuggler, Andrew describes how it was exciting waiting to see how God would provide at his time of need. God always provided, but did so, not according to mans logic but in a kingly matter, not in a grovelling way.

One example of God providing miraculously was when Andrew needed to pay his visa. When Andrew received a visitor the day before he needed to send off his application for a visa, he was confident that the visitor would have come to give him money to pay for the visa. But the visitor was Richard, a man who Andrew had met in the slums in Glasgow. Richard had not come to give, but to ask. Andy explained that he had no money himself to give to Richard, but as he spoke, Andy saw a Shilling on the floor. This shilling was how much Andy needed to pay for his visa which would mean he could stay at the bible school. Rather than keeping the Shilling for himself, Andrew gave the Shilling to Richard. Andy had done what he knew was right, but how would God provide? Minutes later, Andy received a letter and in it was 30 Shillings! God had provided in His way, a Kingly Manner of provision.

GOD CALLS ANDREW BEHIND THE IRON CURTAIN

Leaving bible college in 1955, God guided Andy to attend a Communist trip to Warsaw. This would be the first of many trips into Communist countries.

During his first trip to Warsaw, brother Andrew visited local churches, a bible shop and spoke with Christians in the country. Coming back to Holland, Andrew had lots of opportunities to share about his trip and how Christians lived behind the iron curtain.

Weeks later, the communist party arranged for him to attend a trip to Czechoslovakia. Andrew managed to break away from the organised trip to learn that the church was suffering and that bibles were very scarce. Officials were angry he had broken away from the official tour and had contact with Christians so he was prohibited from entering the country again. But his trip had opened his eyes to the needs of the church behind the iron curtain and this became his mission field.

In the following years, Andy dedicated his life to the needs of the church in the Communist countries. God provided Andrew with a new Volkswagen Beetle and with it Brother Andrew smuggled bibles and literature into the countries in need. Working alone for the first few years, Andrew worked tirelessly in serving the churches behind the iron curtain. When Andrew had finished one trip he would go back to Holland where he would share his experience and then go back to one of the countries. Each trip was full of stories of how God had miraculously provided and led Andrew to meet Godly believers.

ANDREW MARRIES AND HAS A FAMILY

Although serving God in this way was exciting, Andrew felt alone and wanted a wife. In the book God’s Smuggler, Andrew describes how he prayed about a wife three times. The first two times that Brother Andrew asked for a wife God spoke to him clearly through Isaiah 54:1 “The children of the desolate are more than the children of the married”. But Andrew prayed a third time about it, and this time God answered his prayer, reminding him of a lady he worked with at the Ringers chocolate factor, Corrie van Dam. Andrew hadn’t had contact with Corrie for a long time so went to visit her. By God’s grace, Corrie was still single and over a period of several years Andrew and Corrie became great friends. Corrie and Andrew married on June 27th 1958 in Alkmaar, Netherlands.

Corrie was married to a missionary and Andrew very much continued to live like a missionary, smuggling bibles into countries closed countries. Over the years, God blessed Corrie and Andrew with five children, three boys and two girls.

ANDREW STARTS WORKING WITH OTHERS

Andrew kept serving God behind the iron curtain but the work had become difficult to do alone. Andrew thought about how helpful it would be to have a co-worker. This began with a man called Hans and slowly grew until a number of them were smuggling bibles into the communist countries.

SERVING THE WORLD WIDE CHURCH

When the doors to communist Europe were opened in the 1960’s, Brother Andrew began to serve and strengthen the churches in the Middle East and Islamic world.

BROTHER ANDREW RECEIVES RELIGIOUS LIBERTY AWARD IN 2007

On Andy van der Bijl’s 69th birthday, he was honoured by being awarded ‘The Religious Liberty Award’ which was presented by the World Evangelical Fellowship (WEF). The chairman of WEF’s Religious Liberty Commission stated:

“Brother Andrew has been the preeminent example of those from the outside who have excelled in the ministry of encouragement – the many years he has devoted himself to serving the oppressed. His exploits have become legendary as he has crossed borders carrying Bibles, which were liable to confiscation. Time after time God has blinded the eyes of the border guards, and the Bibles got through.

BROTHER ANDREW RESOURCES

God’s Smuggler – Book about Brother Andrew smuggling Bibles.

Will You Lose Your Faith in College

Will you keep your faith in college? Odds are you won’t, at least according to Barna Research. Barna estimates that roughly 70% of high school students who enter college as professing Christians will leave with little to no faith. These students usually don’t return to their faith even after graduation, as Barna projects that 80% of those reared in the church will be “disengaged” by the time they are 29. Will you be one of the 80%? Will you abandon your faith when surrounded by peers who don’t know God? Most people assume their early faith will carry them through their lives. King Joash probably did. He began to reign at age 7 (2 Chronicles 24:1), and he “did what was right in the eyes of the Lord all the days of Jehoiada the priest” (2 Chronicles 24:2), King Joash’s mentor and most trusted advisor. When Jehoiada was alive, Joash faithfully followed God’s laws and made sure others did as well. He even inspired others to give joyfully to God: “All the princes and all the people rejoiced and brought their tax and dropped it into the chest until they had finished” (2 Chronicles 24:10). Joash’s faith certainly seemed genuine. Far Too Easily Swayed But when Jehoiada died, Joash turned to his peers. When the princes of Judah came to visit Joash soon after Jehoiada’s death, the king listened to them. After the princes “paid homage to the king” (2 Chronicles 24:17), which probably meant they flattered him, Joash abandoned the house of the Lord and turned to serve idols. These “friends” may have convinced him that they were open-minded and in touch with popular culture, and that Jehoiada had been too strict and old-fashioned. Joash listened to them and reversed all the good things he had done earlier, even murdering Jehoiada’s son Zechariah when he was questioned. This behavior seems like a shocking turnaround, but it shows that King Joash had likely been trusting in Jehoiada and not God. His faith was not his own. Since he lacked personal conviction, he was easily swayed by faithless people around him. God judged him for his wickedness and he was soon murdered by his own servants. Joash shows us that it doesn’t matter how well we start in the Christian life; it matters how we finish. For Freshmen and Seniors Many of us started strong. We assumed that if we were raised with the right values and involved in church, we would always stay faithful. I believed that. I had a passion for the Lord in high school and college, but as I immersed myself in my career, my church attendance became sporadic and my time with God infrequent and rushed. I found that the less time I spent with the Lord, the less I wanted to know him. My unbelieving coworkers were my closest friends. Originally, I hoped to share my faith with them, but instead they passed on their spiritual indifference to me. They had a subtle but profound influence on my priorities. As my faith was getting watered down, reading the Bible and going to church felt more legalistic than life-giving. It was only when I faced real suffering that my faith became important again. Whether you are a freshman or a senior, if you are heading off to college, you’re in a vulnerable place. It’s easy to assume you’ll develop better spiritual disciplines and get involved in Christian community later on. But as you juggle life’s challenges, it’s tempting to put off pursuing God until you feel more settled, unintentionally falling into the habits of lost people around you. The shift is gradual and often unnoticeable. Three Ways Not to Wander So, what can you do, with God’s help, to be one of the 20% raised in the church who remain faithful through college and into their twenties? First, don’t assume that you won’t drift away — or that if you do drift away, you will eventually come back. We are all vulnerable. Ask God daily for an enduring passion for him. Ask him to give you joy in him alone. Ask him right now to keep your heart from wandering. Second, stay closely connected to God. It may sound trite, or even legalistic, but reading the Bible and praying really are the simple keys to the Christian life. As you read, focus and pay attention rather than mindlessly skimming words to “check off the box.” I love using a Bible reading plan because it takes the guesswork out of what to read each morning. I recommend the Discipleship Journal plan. If you’re reading the Bible regularly for the first time, begin by just reading the New Testament sections each day. Try reading with a pen and paper, jotting down insights, questions, and observations, asking God to open your eyes to see truth and to breathe life into his words (Psalm 119:18). Third, find real Christian fellowship. Plug into a church and a small group or on-campus ministry. Intentionally make Christian friends and spend time with them. Having good Christian friends in college reduces the pressure to conform. The people around us influence us far more than we realize. King Joash is a vivid example of how easy it is to abandon your faith when surrounded by the wrong people. Makeshift Saints Charles Spurgeon, a London preacher in the 1800s, once said, Oh, what a sifter the city of London has been to many like Joash! Many do I remember whose story was like this: they had been to the house of God always . . . and everybody reckoned them to be Christians — and then they came to London. At first, they went . . . to some humble place where the gospel was preached. But after time they thought . . . they worked so hard all the week that they must go out a little into the fresh air on Sunday; and by degrees they found companions who led them, little by little, from the path of integrity and chastity, until the “good young man” was as vile as any on the streets of London; and he who seemed to be a saint, became not only a sinner, but the maker of sinners. None of us is immune from slowly drifting from God. As we see from King Joash’s life, even when we’ve lived an outwardly Christian life, it’s easy to start living like those around us. Yet those who truly know Christ cannot fall away. As 1 John 2:19 says, “If they had been of us, they would have continued with us.” Those who leave the faith never truly possessed it but, as John Calvin said, merely “had only a light and a transient taste of it.” Will You Fall Away? Will you fall away in college? You can fight the current, and hold fast to God. First, “Examine yourselves, to see whether you are in the faith. Test yourselves. Or do you not realize this about yourselves, that Jesus Christ is in you? — unless indeed you fail to meet the test!” (2 Corinthians 13:5). Ask yourself if Jesus is your treasure or if you are only borrowing the faith of those around you. If you have any doubt, commit yourself now to pursue Christ as hard as you pursue anything. But if you genuinely know the Lord, and see evidences of transforming grace in your life, don’t be afraid that you’ll fall away. He will hold you fast. He will strengthen you and help you. He will uphold you with his righteous right hand (Isaiah 41:10). If you are his, then you can be sure “that he who began a good work in you will bring it to completion at the day of Jesus Christ” (Philippians 1:6). Article by Vaneetha Rendall Risner