Dream Big, Talk Big, And Turn Your Faith Loose Order Printed Copy

- Author: Kenneth Copeland

- Size: 550KB | 40 pages

- |

Others like dream big, talk big, and turn your faith loose Features >>

Sit, Walk, And Stand

Dreaming With God - Co-Laboring With God

-160.webp)

Biblical Demonology (A Study Of Spiritual Forces At Work Today)

Holiness, Truth And The Presence Of God

.mobi-160.webp)

The 3 Most Important Things In Your Life

Walking In Wisdom

Conquest Of The Mind

Come Alive

The Individual & World Need

The Road To Glory

About the Book

"DREAM BIG, TALK BIG, AND TURN YOUR FAITH LOOSE" by Kenneth Copeland encourages readers to have faith in God, dream big, and speak positive affirmations to achieve their goals. Through personal stories and biblical teachings, Copeland shows how faith can manifest abundance, success, and fulfillment in life.

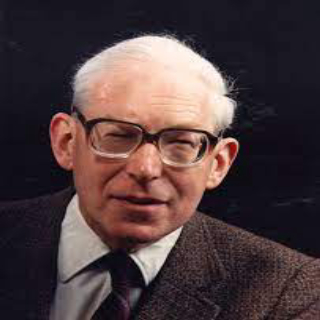

J.I. Packer

Weighing the Beauty and Brevity of Life

It’s been ten years since my father died. A decade. Already? Nearly 20 percent of my lifetime has passed since I last saw him. Where did the time go? My oldest child recently turned 24. To me it seems that almost yesterday I was holding that precious newborn, singing softly to him while slowly pacing in the hospital room. But in reality, I’ve since lived 44 percent of my lifetime. Where did the time go? Thirty-six years ago, I began dating a beautiful 16-year-old girl whom I had the extraordinary privilege of marrying four years later. Scenes from that hot, sunny, summer day when it all began are still vivid to me, and have a hue of new about them. Yet 65 percent of my life has managed to slip by since that monumental moment became a memory. Where did the time go? Where did the time go? Why do we all ask some form of that question — and ask it over and over as the years pass? It’s not like we don’t know. Each of the approximately 3,700 days since my father died, the 8,800 days since my son was born, and the 13,200 days since my wife and I began dating passed just like the ones before it. The days accumulated over time. It’s simple math. But of course, it’s not the math that bewilders us. We’re bewildered by something far more profound — that this life we’ve been given, this significant existence with all its sweet and bitter dimensions, passes so quickly and then is gone. We Are Marvels We all intuitively discern that our lives have profound significance. Even when we’re told they don’t, we don’t really believe it — or if we really do, we no longer want to live. We also intuitively discern that there is profound significance to the great human story-arc, with all of its collective triumphs and tragedies. This isn’t mere human hubris, because most of us, including the greatest among us, have always been cognizant of our smallness in the cosmos. Truly did David pray, When I look at your heavens, the work of your fingers, the moon and the stars, which you have set in place, what is man that you are mindful of him, and the son of man that you care for him? (Psalm 8:3–4) “We are marvels of creation, who long for eternity, yet whose lifespans here are like a mist.” But even in view of our smallness, it’s undeniable that there is something awesome about humanity. Just a brief glance around us shouts this. From where I’m writing (on a laptop computer wirelessly connected to the world!), I see automobiles driving by, a commercial jet flying overhead, an educational institution devoted to helping underprivileged children succeed in school, and a talented gardener carefully cultivating her organic artwork. These phenomena are just part of “normal” daily life for me, yet each represents staggering layers of human ingenuity. And to top it off, my (also wirelessly world-connected) mobile phone has just informed me that NASA has successfully launched its latest rover mission to the planet Mars. Without denying our great and grievous capacities for evil, every single one of us is simply a marvel in our various ranges of intellect, capacities for language and communication, aptitudes for innovation, abilities to impose order upon chaos, and contributions to collective human achievements. Truly did David pray, You have made [man] a little lower than the heavenly beings and crowned him with glory and honor. You have given him dominion over the works of your hands; you have put all things under his feet. (Psalm 8:5–6) God has endowed human beings with the glory and honor of being made in his image (Genesis 1:26–27). This is the profound significance we all intuit, even those who deny it. Our lives are imbued with tremendous meaning. We Are Mists Yet each of our profoundly significant earthly lives, no matter how short or long it lasts, is so brief. We look up to find 10, 24, 36 years have suddenly passed. Repeatedly we’re hit with the realization that our lives “are soon gone, and we fly away” (Psalm 90:10). Truly did David pray, Behold, you have made my days a few handbreadths, and my lifetime is as nothing before you. Surely all mankind stands as a mere breath! (Psalm 39:5) And truly did James say, “What is your life? For you are a mist that appears for a little time and then vanishes” (James 4:14). It’s this existential experience of being marvels and mists that we find bewildering. We find it a strange phenomenon to watch our lives move relentlessly along a continuum, leaving experiences that are massively important to us in an increasingly distant past, while our earthly end — the end of the only reality we’ve ever known — approaches with unnerving speed. It recurrently catches us by surprise. With Eternity in Our Hearts But why do we find this experience strange and surprising? Many experts from various branches of the cognitive and biological sciences venture answers. But just as recounting the math of passing days doesn’t address the strangeness and surprise we feel when we ask, “Where did the time go?” neither do the chemical mechanics of consciousness. And there’s more to the deep longings this whole experience awakens than just the awareness and anticipation of our mortality. Truly did the writer of Ecclesiastes say, [God] has put eternity into man’s heart, yet so that he cannot find out what God has done from the beginning to the end. (Ecclesiastes 3:11) God has given us the ability to conceive of eternity, yet in spite of conferring upon us many marvelous capacities, he has not granted us to peer into eternity past or eternity future, no matter how hard we try. And due to our efforts to seize forbidden knowledge, God has withdrawn our once-free access to simply eat of the tree of life and live forever (Genesis 3:22–24). We are marvels of creation, whose lives are imbued with great meaning, who long for eternity, yet whose lifespans here are like a mist. No wonder we find time mystifying. Teach Us to Number Our Days Our strange experience of the passing of time is more than a by-product of consciousness, more than mere existential angst over mortality. It is a reminder and a pointer. “God has reopened for us the way to the tree of life, to eternal life, and that way is through his Son, Jesus.” It is a reminder that we are contingent creatures and that the profound significance we intuitively know our lives possess is derived significance, not self-conferred significance. Though created in the likeness of God and given marvelous capacities, we are not self-existent or self-determining like God. Rather, “in him we live and move and have our being” (Acts 17:28), receiving from him our “allotted periods” of life and “the boundaries of [our] dwelling place” (Acts 17:26). And the brevity of those allotted periods of life are meant to make us cry out, “O Lord, make me know my end and what is the measure of my days; let me know how fleeting I am!” (Psalm 39:4). And our experience of deep heart longing for eternity in the face of such brevity is a pointer that we are actually designed for such a thing as eternal life. For those who have eyes to see, this is a gospel pointer. For God has reopened for us the way to the tree of life, to eternal life, and that way is through his Son, Jesus (John 3:16; 14:6; Romans 6:23; Revelation 2:7). Those moments when we ask, “Where did the time go?” are reminders that “all flesh is grass, and all its beauty is like the flower of the field. The grass withers, the flower fades when the breath of the Lord blows on it” (Isaiah 40:6–7). And they are pointers to the reality that though our “days are like grass,” yet “the steadfast love of the Lord is from everlasting to everlasting on those who fear him” (Psalm 103:15–17). Those moments come to us in order to “teach us to number our days that we may get a heart of wisdom” (Psalm 90:12).