When The Enemy Is Already Inside Order Printed Copy

- Author: Dr D. K. Olukoya

- Size: 342KB | 16 pages

- |

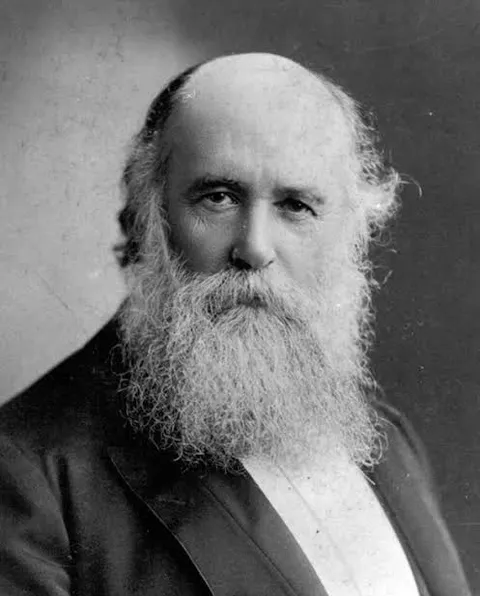

John Alexander Dowie

By John Alexander Dowie (1847 – 1907)

I sat in my study in the parsonage of the Congregational Church at Newtown, a suburb of the beautiful city of Sydney, Australia. My heart was very heavy, for I had visited the sick and dying beds of more than thirty of my flock, and I had cast the dust to its kindred dust into more than forty graves within a few weeks. Where, oh where, was He Who used to heal His suffering children? No prayer for healing seemed to reach His ear, and yet I knew His hand had not been shortened. Still it did not save from death even those for whom there was so much in life to live for God and others. Strong men, fathers, good citizens, and more than all, true Christians sickened with a putrid fever, suffered nameless agonies, passed into delirium, sometimes with convulsions, and then died.

Oh, what aching voids were left in many a widowed or orphaned heart. There were many homes where, one by one, the little children, the youths and the maidens lay stricken, and after a hard struggle with the foul disease, they too, lay cold and dead. It seemed sometimes as if I could almost hear the triumphant mockery of evil ringing in my ear whilst I spoke to the bereaved ones the words of Christian hope and consolation. Disease, the foul offspring of its father, Satan, and its mother Sin, was defiling and destroying the earthly temples of God’s children and there was no deliverance.

There I sat with sorrow-bowed head for my afflicted people, until the bitter tears came to relieve my burning heart. Then I prayed for some message, and oh, how I longed to hear some words from Him Who wept and sorrowed for the suffering long ago, a Man of Sorrows and Sympathies. The words of the Holy Ghost inspired In Acts 10:38, stood before me all radiant with light, revealing Satan as the Defiler, and Christ as the Healer. My tears were wiped away, my heart strong, I saw the way of healing, and the door thereto was opened wide, so I said, “God help me now to preach the Word to all the dying around, and tell them how Satan still defiles, and Jesus still delivers, for He is just the same today.”

A loud ring and several raps at the outer door, a rush of feet, and there at my door stood two panting messengers who said, “Oh, come at once, Mary is dying; come and pray. “With just a feeling as a shepherd has who hears that his sheep are being torn from the fold by a cruel wolf, I rushed from my house, ran without my hat down the street, and entered the room of the dying maiden. There she lay groaning and grinding her clenched teeth in the agony of the conflict with the destroyer. The white froth, mingled with her blood, oozing from her pale and distorted mouth. I looked at her and then my anger burned. “Oh,” I thought, “for some sharp sword of heavenly temper keen to slay this cruel foe who is strangling that lovely maiden like an invisible serpent, tightening his deadly coils for a final victory.”

In a strange way, It came to pass; I found the sword I needed was in my hands, and in my hand I hold it still and never will I lay It down. The doctor, a good Christian man, was quietly walking up and down the room, sharing the mother’s pain and grief. Presently he stood at my side and said, “Sir, are not God’s ways mysterious?” Instantly the sword was flashed in my hand, the Spirit’s sword, the Word of God. “God’s way?!” I said, pointing to the scene of conflict, “How dare you call that God’s way of bringing His children home from earth to Heaven? No sir, that is the devil’s work and it is time we called on Him Who came to destroy the work of the devil, to slay that deadly foul destroyer, and to save this child. Can you pray, Doctor, can you pray the prayer of faith that saves the sick?” At once, offended at my words, my friend was changed, and saying,” You are too much excited, sir, it is best to say ‘God’s will be done,’” and he left the room.

Excited?! The word was quite inadequate for I was almost frenzied with divinely imparted anger and hatred of that foul destroyer, disease, which was doing Satan’s will. “It is not so,” I exclaimed, “no will of God sends such cruelty, and I shall never say ‘God’s will be done’ to Satan’s works, which God’s own Son came to destroy, and this is one of them.” Oh, how the Word of God was burning in my heart: “Jesus of Nazareth went about doing good, and healing all that were oppressed of the devil; for God was with Him.” And was not God with me? And was not Jesus there and all His promises true? I felt that it was even so, and turning to the mother I inquired,” Why did you send for me?” To which she answered, “Do pray, oh pray for her that God may raise her up.” So we prayed.

What did I say? It may be that I cannot recall the words without mistake, but words are in themselves of small importance. The prayer of faith may be a voiceless prayer, a simple heartfelt look of confidence into the face of Christ. At such moment, words are few, but they mean much, for God is looking at the heart. Still, I can remember much of that prayer unto this day, and asking God to aid, I will attempt to recall it. I cried, “Our Father, help! and Holy Spirit, teach me how to pray. Plead Thou for us, oh, Jesus, Savior, Healer, Friend, our Advocate with God the Father. Hear and heal, Eternal One! From all disease and death, deliver this sweet child of yours. I rest upon the Word. We claim the promise now. The Word is true, ‘I am the Lord that heals thee.’ Then heal her now. The Word is true, ‘I am the Lord, I change not.’ Unchanging God, then prove Yourself the healer now. The Word is true. ‘These signs shall follow them that believe in My Name, they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover.’ And I believe and I lay hands in Jesus’ Name on her and claim this promise now. Your Word is true. ‘The prayer of faith shall save the sick. Trusting in You alone. I cry. Oh, save her now, for Jesus’ sake. Amen!”

Then, the maid lay in sleep so deep and sweet that the mother asked in a low whisper, “Is she dead?” “No,” I answered, in a whisper lower still. “Mary will live; the fever is gone. She is perfectly well and sleeping as an infant sleeps.” I was smoothing the long dark hair from her now peaceful brow, and feeling the steady pulsation of her heart and cool moist hands. I saw that Christ had heard, and that once more, as long ago in Peter’s house, “He touched her and the fever left her.” Turning to the nurse, I said, “Get me at once, please, a cup of cocoa and several slices of bread and butter.” Beside the sleeping maid we sat quietly and almost silently until the nurse returned, and then I bent over her and snapping my fingers called, “Mary!”

Instantly she woke, smiled and said, “Oh, sir, when did you come? I have slept so long;” then stretching her arms out to meet her mother’s embrace, she said, “Mother, I feel so well.” “And hungry, too?” I asked, pouring some of the cocoa in a saucer and offering it to her when cooled by my breath. “Yes, hungry too,” she answered with a little laugh, and drank and ate again, and yet again until all was gone. In a few minutes, she fell asleep, breathing easily and softly. Quietly thanking God. We left her bed and went to the next room where her brother and sister also lay sick of the same fever. With these two, we prayed and they were healed too. The following day all three were well and in a week or so they brought me a little letter and a gift of gold, two sleeve links with my monogram, which I wore for many years. As I went away from the home where Christ as the Healer had been victorious, I could not but have somewhat in my heart of the triumphant song that rang through Heaven, and yet I was not a little amazed at my own strange doings, and still more at my discovery that He is just the same today.

Excerpt from the Sermons of John Alexander Dowie Champions of Faith by Gordon Lindsay

By John Alexander Dowie (1847 – 1907)

I sat in my study in the parsonage of the Congregational Church at Newtown, a suburb of the beautiful city of Sydney, Australia. My heart was very heavy, for I had visited the sick and dying beds of more than thirty of my flock, and I had cast the dust to its kindred dust into more than forty graves within a few weeks. Where, oh where, was He Who used to heal His suffering children? No prayer for healing seemed to reach His ear, and yet I knew His hand had not been shortened. Still it did not save from death even those for whom there was so much in life to live for God and others. Strong men, fathers, good citizens, and more than all, true Christians sickened with a putrid fever, suffered nameless agonies, passed into delirium, sometimes with convulsions, and then died.

Oh, what aching voids were left in many a widowed or orphaned heart. There were many homes where, one by one, the little children, the youths and the maidens lay stricken, and after a hard struggle with the foul disease, they too, lay cold and dead. It seemed sometimes as if I could almost hear the triumphant mockery of evil ringing in my ear whilst I spoke to the bereaved ones the words of Christian hope and consolation. Disease, the foul offspring of its father, Satan, and its mother Sin, was defiling and destroying the earthly temples of God’s children and there was no deliverance.

There I sat with sorrow-bowed head for my afflicted people, until the bitter tears came to relieve my burning heart. Then I prayed for some message, and oh, how I longed to hear some words from Him Who wept and sorrowed for the suffering long ago, a Man of Sorrows and Sympathies. The words of the Holy Ghost inspired In Acts 10:38, stood before me all radiant with light, revealing Satan as the Defiler, and Christ as the Healer. My tears were wiped away, my heart strong, I saw the way of healing, and the door thereto was opened wide, so I said, “God help me now to preach the Word to all the dying around, and tell them how Satan still defiles, and Jesus still delivers, for He is just the same today.”

A loud ring and several raps at the outer door, a rush of feet, and there at my door stood two panting messengers who said, “Oh, come at once, Mary is dying; come and pray. “With just a feeling as a shepherd has who hears that his sheep are being torn from the fold by a cruel wolf, I rushed from my house, ran without my hat down the street, and entered the room of the dying maiden. There she lay groaning and grinding her clenched teeth in the agony of the conflict with the destroyer. The white froth, mingled with her blood, oozing from her pale and distorted mouth. I looked at her and then my anger burned. “Oh,” I thought, “for some sharp sword of heavenly temper keen to slay this cruel foe who is strangling that lovely maiden like an invisible serpent, tightening his deadly coils for a final victory.”

In a strange way, It came to pass; I found the sword I needed was in my hands, and in my hand I hold it still and never will I lay It down. The doctor, a good Christian man, was quietly walking up and down the room, sharing the mother’s pain and grief. Presently he stood at my side and said, “Sir, are not God’s ways mysterious?” Instantly the sword was flashed in my hand, the Spirit’s sword, the Word of God. “God’s way?!” I said, pointing to the scene of conflict, “How dare you call that God’s way of bringing His children home from earth to Heaven? No sir, that is the devil’s work and it is time we called on Him Who came to destroy the work of the devil, to slay that deadly foul destroyer, and to save this child. Can you pray, Doctor, can you pray the prayer of faith that saves the sick?” At once, offended at my words, my friend was changed, and saying,” You are too much excited, sir, it is best to say ‘God’s will be done,’” and he left the room.

Excited?! The word was quite inadequate for I was almost frenzied with divinely imparted anger and hatred of that foul destroyer, disease, which was doing Satan’s will. “It is not so,” I exclaimed, “no will of God sends such cruelty, and I shall never say ‘God’s will be done’ to Satan’s works, which God’s own Son came to destroy, and this is one of them.” Oh, how the Word of God was burning in my heart: “Jesus of Nazareth went about doing good, and healing all that were oppressed of the devil; for God was with Him.” And was not God with me? And was not Jesus there and all His promises true? I felt that it was even so, and turning to the mother I inquired,” Why did you send for me?” To which she answered, “Do pray, oh pray for her that God may raise her up.” So we prayed.

What did I say? It may be that I cannot recall the words without mistake, but words are in themselves of small importance. The prayer of faith may be a voiceless prayer, a simple heartfelt look of confidence into the face of Christ. At such moment, words are few, but they mean much, for God is looking at the heart. Still, I can remember much of that prayer unto this day, and asking God to aid, I will attempt to recall it. I cried, “Our Father, help! and Holy Spirit, teach me how to pray. Plead Thou for us, oh, Jesus, Savior, Healer, Friend, our Advocate with God the Father. Hear and heal, Eternal One! From all disease and death, deliver this sweet child of yours. I rest upon the Word. We claim the promise now. The Word is true, ‘I am the Lord that heals thee.’ Then heal her now. The Word is true, ‘I am the Lord, I change not.’ Unchanging God, then prove Yourself the healer now. The Word is true. ‘These signs shall follow them that believe in My Name, they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover.’ And I believe and I lay hands in Jesus’ Name on her and claim this promise now. Your Word is true. ‘The prayer of faith shall save the sick. Trusting in You alone. I cry. Oh, save her now, for Jesus’ sake. Amen!”

Then, the maid lay in sleep so deep and sweet that the mother asked in a low whisper, “Is she dead?” “No,” I answered, in a whisper lower still. “Mary will live; the fever is gone. She is perfectly well and sleeping as an infant sleeps.” I was smoothing the long dark hair from her now peaceful brow, and feeling the steady pulsation of her heart and cool moist hands. I saw that Christ had heard, and that once more, as long ago in Peter’s house, “He touched her and the fever left her.” Turning to the nurse, I said, “Get me at once, please, a cup of cocoa and several slices of bread and butter.” Beside the sleeping maid we sat quietly and almost silently until the nurse returned, and then I bent over her and snapping my fingers called, “Mary!”

Instantly she woke, smiled and said, “Oh, sir, when did you come? I have slept so long;” then stretching her arms out to meet her mother’s embrace, she said, “Mother, I feel so well.” “And hungry, too?” I asked, pouring some of the cocoa in a saucer and offering it to her when cooled by my breath. “Yes, hungry too,” she answered with a little laugh, and drank and ate again, and yet again until all was gone. In a few minutes, she fell asleep, breathing easily and softly. Quietly thanking God. We left her bed and went to the next room where her brother and sister also lay sick of the same fever. With these two, we prayed and they were healed too. The following day all three were well and in a week or so they brought me a little letter and a gift of gold, two sleeve links with my monogram, which I wore for many years. As I went away from the home where Christ as the Healer had been victorious, I could not but have somewhat in my heart of the triumphant song that rang through Heaven, and yet I was not a little amazed at my own strange doings, and still more at my discovery that He is just the same today.

Excerpt from the Sermons of John Alexander Dowie Champions of Faith by Gordon Lindsay

10 Times Denzel Washington was Candid about His Christian Faith

Throughout his career, actor Denzel Washington has been open about his faith. Most recently, Washington reportedly offered some Biblical-inspired wisdom to actor Will Smith after he slapped comedian Chris Rock at the 2022 Oscars. Here's a look at 10 times Washington has talked about faith and its impact on his life and career. Denzel Washington, Washington shares his supernatural experience coming to Christ 1. Oscars 2022 on Smith-Rock Incident "Denzel said to me a few minutes ago, he said, 'At your highest moment, be careful— that's when the devil comes for you,'" Smith said during the Oscars while accepting his award. Smith was referring to the commercial break when Washington approached Smith after Smith rushed on stage to slap Rock for joking about Smith's wife. Washington's statement to Smith refers to 1 Peter 5:8, which says, "Be alert and of sober mind. Your enemy the devil prowls around like a roaring lion looking for someone to devour." 2. Showtime's Desus & Mero Podcast 2022 on talent "One of the most important lessons in life that you should know is to remember to have an attitude of gratitude, of humility, understand where the gift comes from," Washington said. "It's not mine, it's been given to me by the grace of God." 3. New York Times 2021 Interview on spiritual warfare "This is spiritual warfare. So, I'm not looking at it from an earthly perspective," Washington told the New York Times. "If you don't have a spiritual anchor, you'll be easily blown by the wind, and you'll be led to depression. "The enemy is the inner me," Washington added. "The Bible says in the last days – I don't know if it's the last days, it's not my place to know – but it says we'll be lovers of ourselves. The number one photograph today is a selfie, 'Oh, me at the protest.' 'Me with the fire.' 'Follow me.' 'Listen to me.'" 4. 2021 "The Better Man Event" on the role of a man "The John Wayne formula is not quite a fit right now. But strength, leadership, power, authority, guidance, [and] patience are God's gift to us as men. We have to cherish that, not abuse it. "I hope that the words in my mouth and the meditation of my heart are pleasing in God's sight, but I'm human. I'm just like you," he said. 5. 2021 Religion News Service Interview on how his faith impacted his film, "Journal for Jordan" "The spirit of God is throughout the film. Charles is an angel. I'm a believer. Dana's a believer. So that was a part of every decision, hopefully, that I tried to make. I wanted to please God, and I wanted to please Charles, and I wanted to please Dana." "I am a member, also a member of the (Cultural Christian Center) out here in New York. I have more than one spiritual leader in my life. So there's different people I talk to, and I try to make sure I try to put God first in everything. I was reading something this morning in my meditation about selfishness and how the only way to true independence is complete dependence on the Almighty." 6. Instagram Live with Pastor A.R. Bernard of Christian Cultural Center on his salvation "I was filled with the Holy Ghost, and it scared me. I said, 'Wait a minute, I didn't want to go this deep, I want to party,'" Washington said of the time he gave his life to Christ. "I went to church with Robert Townsend, and when it came time to come down to the altar, I said, 'You know this time, I'm just going to go down there and give it up and see what happens. I went in the prayer room and gave it up and let go and experienced something I've never experienced in my life." 7. 2017 The Christian Post Interview on advice for millennials "I would say to your generation – find a way to work together because this is a very divisive, angry time you're living in, unfortunately, because we didn't grow up like that," he said. "I pray for your generation," he added. "What an opportunity you have! Don't be depressed by it because we have to go through this, we're here now. You can't put that thing back in the box." 8. 2017 Screen Actors Guild Awards "I'm a God-fearing man. I'm supposed to have faith, but I didn't have faith," he said, according to Faith Wire. "God bless you all, all you other actors." 9. 2015 Church of God in Christ's Charity Banquet "Through my work, I have spoken to millions of people. In 2015, I said I'm no longer just going to speak through my work. I'm going to make a conscious effort to get up and speak about what God has done for me." 10. 2007 Reader's Digest Interview on his faith "I read the Bible every day. I'm in my second pass-through now, in the Book of John. My pastor told me to start with the New Testament, so I did, maybe two years ago. Worked my way through it, then through the Old Testament. Now I'm back in the New Testament. It's better the second time around." Amanda Casanova ChristianHeadlines.com Contributor

-480.webp)